Revolution? Really!

Lately there seems to be something very right-wing about being on the ‘Left’. I’m not really sure what the ‘Left’ actually stands for anymore. Until the 1990’s it was the place where you would find a broad array of Marxists, Trotskyites, Labour Party members, Socialists, and even Shinners. All partook of an identity easily distinguished from the ‘Right’, where there was a corresponding mix of Thatcherites, Reaganites, ‘trickle-down’ economists, and extreme libertarians.

Oh boy! Things were easy then. Even if you didn’t sympathize with the Left, agreement with the near-ubiquitous Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND) made you one by proxy. The Left was a vast political and psychological landscape, and it was almost impossible to reach another political standpoint without crossing its borders.

In essence, the Left was once defined by its distinction from the Right; the big Other of Nuclear Power, the Corporation and ‘profits before people’. It was real, accessible, unavoidable, and an essential alternative to the establishment; a crucial political counterbalance to the dominant side of politics. It was, ostensibly, about ‘ordinary-people’, higher taxes for the rich and social investment.

For a long time the Left held the intellectual high ground. Existentialists, artists, poets; Kafka, Camus, Beckett, Joyce, Hemingway, Steinbeck, and many more, were all on-side, raging in their own way ‘against the machine’; against religion, blind conformity, and the inhumanity of a comfortably-numb establishment.

You just had to grab a copy of Kafka’s The Castle, slip into a pair of Birkenstock’s, order a latte, or smoke on a clove cigarette, to declare yourself a Leftie. Today those same cafes are populated with ‘techies’, hurriedly devouring avocado toast, perusing the Economist, fiddling with a ‘fit-bit’, and asking Siri if Tesla shares are on the rise.

So where have they all gone, those Beatniks and the latter-day Chés? Today, distinguishing ideological differences between ruling and opposition parties in most Western democracies requires superhuman vision, or no vision at all. Existentialist dialogue about literature or philosophy is rarely found in mainstream media, instead relegated to academia, or that strange cabal, referred to disparagingly as ‘intellectuals’.

What we are left with is an exaggerated respect for the titans of big business, the market, and venerate unlimited economic growth.

RTÉ Science & Technology Correspondent Will Goodbody gets a rare insight into the functions of Apple’s European Headquarters in Cork https://t.co/DYL0oHVqYT

— RTÉ News (@rtenews) December 15, 2017

What Colour are Irish Apples?

Perhaps the Left simply grew old and frail? The fruit of the early labours brought sufficient liberty and licence to sire a more politically effete ‘snowflake generation’. Perhaps their offspring have simply ‘sold out’, or been wooed into the corporate fold, via a co-dependence on social media and semi-legal sedatives?

Yet today in Ireland our government is not simply failing to tax corporations progressively, but actively trying to return tax revenues to its corporate ‘benefactors.’

Allegiance of the national media to the Government’s ongoing legal battle to return tax revenue to Apple has been crucial. Thus, in one article published on the RTE News website in September 2019 entitled ‘The Apple tax case: All you need to know,’ RTE’s Business editor Will Goodbody concludes his analysis with the following summation:

But wouldn’t we like to get our hands on the cash?

That would seem like a great idea on the face of it, and one advocated by quite a few politicians.

At a time when we are facing significant economic uncertainty with Brexit, a global economic downturn, trade wars and more, €14.3bn would go a long way towards resolving many problems.

However, that would only be a short term gain and may only go to reinforce claims that Ireland is a tax haven – something the Government strongly denies.

In the long-run the argument made by other politicians and experts is that Ireland would be far better off if it and Apple won their appeals.

This would protect Ireland’s reputation and send a strong message out to the international investment community that Ireland is a safe place to invest, they claim.

Of course, there is much change afoot in the international corporate tax environment anyway, particularly through the OECD. Within the country too, the Government has taken steps to clamp down on corporation tax loopholes.

So while a €14.3bn windfall might seem very attractive, for a small open economy like ours that is so dependent on inward investment and a reputation for doing clean business, it actually could prove massively damaging.

The stakes are very high for all concerned and the next hand will be played on Tuesday morning in Luxembourg.

Note that the argument for accepting the tax arises from “quite a few politicians”, whilst the case to return the tax is made “by other politicians and experts”. Apple must be permitted to avoid paying taxes, otherwise they might take their sugar elsewhere. At least that’s the “expert” view.

Goodbody’s supposedly impartial analysis is really “all you need to know”.

Notably, prior to the Covid-19 pandemic whilst in opposition Green Party leader Eamon Ryan repeatedly stated he hoped the government would drop its legal challenge to the E.U. judgment, and accept the unpaid tax (2). Yet whilst negotiating the Programme for Government this enormous issue, slipped down the Green agenda.

It’s reached the stage where we should not be asking where are the Left, but rather where have our collective morals disappeared altogether with regard to a company paying its dues.

Revealingly, in 1968 the rate of corporation tax in the U.S. stood at 52.8%. Since then it has dropped steadily to the present rate of 21%. Socialism is an expensive business which requires taxation revenue.

Halcyon days.

Socialism is the political expression of Leftist ideology. In calling for a Renewed Deal, David Langwallner argued recently that Socialism may have been undermined by Socialism itself:

In Late 1970’s Britain in particular, the excess of socialism were becoming obvious, with the three day working week, refuse on the streets, and the stranglehold of government by the Unions. In circumstance where initiative was stifled Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Regan championed the old doctrine of unregulated markets.

What Langwallner’s critique hints at is that when the unions became strong, workers in many industries became lazier and devoid of initiative. There is also the U.S. Republican assumption that socialism has the same effect upon the poor. The welfare or unionised notion of paying people to work less, or not at all, may indeed be the ‘terrible’ underbelly of socialism, but this notion needs to be unpacked, with impartiality.

When the poor are given sugar in the context of a political philosophy that values sugar (or material wealth), as the measure of success, it is not unreasonable to expect that teeth will rot and guts bulge. This is, however, true of the poor and of the not-so-poor. The problem with sugar is that it dampens hunger for more demanding or nutritional alternatives.

What do people generally do with the essential supports from a socialist system, once the absolute essentials are paid for? If there is something remaining, do they buy; beer, smokes, take-aways, or books to read? Some might choose the latter, but let’s face it, they are hardly in a majority.

The ‘poor’, are encouraged to become more ‘educated’ and ‘literate’. Yet, all too often, getting homework done, or having academic interests is only really possible as one ascends through the class structure of Western society. Education is impeded at an early stage by classrooms that are overcrowded. Literacy or literature has little social currency, if you don’t believe me ask a poet.

The poor live within a society that values wealth above most other qualities. The education system hardly teaches children to become autonomous individuals, insisting on conformity to a particular curriculum. Children are primarily educated to become ‘workers’ or ‘professionals.’

The poor respond to their marginalization through recourse to booze, smokes, sugar, football, or pot. Or someone can vent frustrations or social impotence upon those vulnerable who are closer to home.

James Joyce described this process in Dubliners in the stories of ‘Counterparts,’ where the ‘hero’ Farrington is lauded in a pub after work, for a witty retort to his hectoring superior’s question: ‘Do you take me for an utter fool?’ His response ‘I don’t think, sir, that that’s a fair question to ask me’.

He has his drinking buddies in stitches, but ends the day realising the joke may have cost him his job, which shines an unforgiving light on his failings. Returning home:

He cursed everything he had done for himself in the office, pawned his watch, and he had not even got drunk.” At home his son becomes the scapegoat: Farrington severely beats him with a stick, for failing to keep the fire alight.

Joyce subtly illustrates the inferiority and anger we inflict on others because of our own socially reinforced notions of success; and what it means to be a ‘winner’ or a ‘loser’. Human psychology changes very little.

A Deeper Analysis

What of the assertion that the socialist transaction cannot avoid reminding both beneficiaries and benefactors, of who the ‘winners’ and the ‘losers’ really are? Now we are upon the fringes of a different kind of question. This is not to doubt the requirement for social supports, but to interrogate more deeply the psychology of the participants, the ideological context, and the material nature of the transaction itself.

We have been playing different versions of the same capitalist game since the advent of civilization, in amassing personal wealth. Yet, the irony is that human-mortality resolutely confirms ownership as a delusion. Every ‘thing’ we think we own, is in fact, merely borrowed for a time. The plastic bags within which we carry home our groceries, may well be around for longer than ourselves.

Science, technology, government and mass production have freed us from a necessity to hoard, but it continues in different forms, as we make it our life’s work. Perhaps we are simply stupid or perhaps instead we have been conditioned to fear instead of trust? Wealth provides security and assuages certain fears. Indeed, if we could only trust our politicians to deliver on their promises, we might be less inclined to hoard, and even happily pay our taxes.

In the decline of the Left, Democracy succumbs to a capitalism that sustains corporations, the market and a state bureaucracy. Arguably Democracy has foundered, and an evolution, or a new kind of ‘social experiment’ is long overdue. Impending environmental collapse means the window for change is fading fast.

In the present version of ‘the game’, there are plenty of ‘losers’. Social welfare is the essential mechanism whereby those ‘losers’ are protected from falling too far from the field. The game is indeed an expensive one. As such, Socialism is a kind of charity that is derived from the taxes of those who are not losing badly, or (in theory at least) from the taxes of those who are not losing at all.

Yet, what becomes of Socialism when it is trapped within the wealth-game and dependent on the charity of the winners? What is the nature of the relationship between giver and receiver? The latter ought to be grateful, whilst the former cannot escape feeling self-righteous, magnanimous, or even ‘Christian’. Much of this ‘sentiment’ is superficial, but what if we dig a little deeper?

What if the recipient of socialist charity feels resentment towards his benefactor? Or what if his outlook is merely ambiguous, or he could not care less about a state that has generously endowed him with entitlements like a home, a medical card and welfare payments? If he lacks gratitude, he is apparently not fulfilling his part of the transaction. But if he experiences gratitude, he is demoralized.

What if the poor are not as thoughtful as some presume? Perhaps they see the relative wealth of the State, and resent that they are dining on crumbs, however hearty? We in the middle classes expect recipients of our social charity to be grateful, at least to the extent that they refrain from breaking into our homes and disturbing the islands in our kitchens.

But what if the poor man is an angry man, and not a grateful demoralized slave? What if he is uncertain as to why he is angry? What if he defines his material wealth, his status, through the same relativist lens as his benefactor? He has clearly ventured outside the contract; he is not playing by the rules. He may even become a criminal.

Mainstream media displays an obsession with ‘obvious’ criminals. Yet the hidden criminality of tax avoidance is immune from daily scrutiny or moral indignation.

This by @ConorGallaghe_r on the #AnaKriegel case is a very long, very difficult read. This gorgeous schoolgirl, so close to her loving parents, taken from them in the worst possible circumstances. She's gone. All that's left is a horror story: https://t.co/AXJhDw89nt @IrishTimes

— Roisin Ingle (@roisiningle) June 18, 2019

But what if our ‘obvious criminal’ is merely demonstrating his anger by pissing on the street, or through petty crime, littering, graffiti or larceny? What if his addiction or self-destruction is a symptom of losing the game? What if much criminality is instead, the sublimation of something deeper? The criminal participates in a different game, where he doesn’t depend on charity and has an equal if not a significantly improved chance of becoming a winner?

We are want to believe that they are indeed grateful for our socialist charity, and immune to the material-relativism that has generated the very excesses that makes such largesse possible. Within this narrative criminals are simply ‘bad-eggs’ requiring incarceratation, re-education, rehabilitation, punishment or perhaps simply entertainment with a little bit of sugar.

Alain de Botton described a ‘Status Anxiety’ where the relatively poor are just as unhappy as the relatively rich. How unhappiness manifests in either ‘class’ is different of course: rich and poor display peculiar versions of the same dis-ease. Neither are immune from feeling like a ‘loser’, and indeed, becoming a ‘winner’ is often far less rewarding, than assumed.

It is only when we have the courage to reject the wealth-game that permits and demands us to be charitable, that ‘we’ begin to reject both cause and effect. At best however, we wallow in the intellectual mire, of continually trying to change the rules; to make society more inclusive, accessible and accommodating for all the players. We never tire of trying to preserve the game and construct what Slavoj Zizek describes as ‘Capitalism with a human face.’

Counter Argument

The counter argument is often that without wealth, charity becomes impossible. Perhaps we are all now ‘trickle-down’ economists.

There is, however, in this modern era, a reasonable reply, requiring a modicum of thought. It states with philosophical confidence, that without wealth, charity itself becomes largely unnecessary. This ‘radical’ assertion is based on a progressive assessment of our social progress, of our technology, our science, our medicine and our ability to provide for honest human needs.

There is today, more than enough for everyone, but only when we begin to define ‘enough’ outside of the context of relativism. Yet it’s a truth that has yet to find a political home, and be lived up to by ‘we the people’. We should not despair, however, the Scandinavian nations, at least, seem to have secured a few lifeboats and embarked on a voyage of political discovery.

On a practical level, the question then arises: how might we elect politicians who will lead by the contrary example of rejecting the wealth-game, instead of the usual perfunctory review of the rule-book?

I believe we must listen to the hidden articulations of our ‘obvious’ criminals, sanction the un-obvious criminals, and honestly reject our material superfluity.

If we should ever embark upon a different game, politicians will have to tell us what many do not wish to hear. That too much money is not good for us. They will have to insist that the game itself is the cause of our dis-eases.

Leo Varadkar is on "the extreme right" of FG, FF's socialism is bogus @BrendanHowlin tells @hlinehan & @fiachkelly https://t.co/7KyKJPpDXq

— Audio from The Irish Times (@IrishTimesAudio) February 2, 2017

It is simply inhuman to live in a society that does not hold socialist values; and yet we cannot avoid Oscar Wilde’s astute observation in The Soul of Man Under Socialism that: ‘charity degrades and demoralizes. It is immoral to use private property in order to alleviate the horrible evils that result from the institution of private property.’

We must move our political philosophy beyond the Victorian ideal of a charitable socialism, into a realm of thinking that renders charity itself unnecessary. To do so we must consider human beings as being far more than consumers. We must recognise that the poor don’t require a decent and philosophically grounded education, we all do.

To think philosophically or even intelligently, we must re-evaluate our collective love of sugar. We must dispense with excessive material possession, status anxiety, eternal youth, and fast fashion. The measures of success and the benchmarks for respect within a shared society must be turned on their fat ugly heads.

Such a society would be one where each human being is recognised as being born with something successful already contained within. It need not be consumed or purchased or attained, it is already hard-wired, and needs only to be introduced to the world by the midwife of old Philosophy. If the Left is to become viable again, it must stand as an antagonism to the irrational consumptive ideals that have come to define the individual, society and state. In order to do so, the Left must own a pure philosophy, and lead by example.

The Extinction of the Left

It is interesting to note that many, if not most of the big Corporate entities we might consider to be on the Right, emerged from ostensibly Leftie origins.

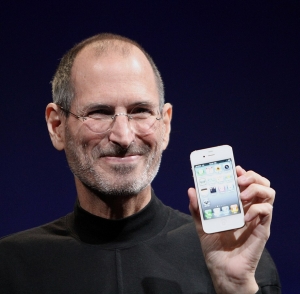

Steve Jobs, ‘Leftie’ origins.

Steve Jobs who founded Apple, was an orphan of mixed race parentage. The start-up began in a garage with a few pals, followed by a rise to fame and fortune with a ‘vision’ to bring an ‘alternative’ to the market, a computer for ordinary people. Likewise all the main players from Starbucks coffee, Facebook, Google etc., began their lives with the lefty dream-tropes, of grass-roots change.

In Ireland, we had something of the same transformation of U2 the band, into U2 the industry. We see this evolution in erstwhile Lefty publications like the Guardian, who begin on the Left, and then drift inexorably right-ward, becoming increasingly dependent upon the market, or the ‘clickbait’ of social media.

Arguably the same process has ultimately transformed RTE. It’s income from mandatory TV licences was supposed to insulate it from market forces. Yet it is now caught in a bind between dependent on licence fees and the market revenues it derives from advertisements. The present salaries of its top presenters are as publicised as they are ignored. Early on, the transformation was objected to by one of its most accomplished and renowned directors, Bob Quinn, who resigned as an RTE producer in 1969, objecting to the increasing influence of market imperatives.

Today, stuck between the pay-masters of Government and the Market; ideas uncomfortable to either, are rarely countenanced. RTE’s financial dependence define its intellectual boundaries. What has evolved, might be described as something of a national ‘metronome’, ticking hypnotically between two defined limits; a fidelity to the ruling regime (whomever they may be) and a strict conformity to market ideology. Until RTE is liberated from itself, (and we from it), Ireland’s intellectual paralysis seems likely to remain.

Too often, the Left is contaminated by the same wealth that it seeks on behalf of the proletariat. Thus as Lefties become rich, we evolve slightly different values. The process of the son growing up and murdering his father, is as old as Greek mythology. A cynic might even suggest that the purpose of the Left is simply to nurse the children of the Right, until they are mature enough to leave the den and hunt for themselves.

The Meek shall Inherit the Earth

It appears that you have to be poor to be on the Left. The further one moves from poverty into the middle classes, the more of a material ‘success’ one makes of oneself, the more difficult it becomes to declare oneself a Lefty. As most society get wealthier the Leftist demand for ‘more money’ for the relatively poor is increasingly difficult to sustain. Terms like ‘looney left’ are increasingly grounded in empirical truths.

During the Lefty campaign against water charges in 2014, then Tánaiste and leader of the Labour Party Joan Burton answered a questions in the Dáil with words that may have led to the demise of her career:

“All the protesters I have seen seem to have extremely expensive phones, tablets and video cameras.” [They]… “put Hollywood in the ha’penny place.

Joan Burton says water charge protesters are using "expensive phones, tablets" to film demos http://t.co/MTAL09UPrV pic.twitter.com/LAorsSC9hX

— Irish Daily Mirror (@IrishMirror) October 9, 2014

It serves to remind us that only ‘genuine,’ ‘deserving’ poor should lay claim to being on the Left. The brutal irony is that the statement was made by the leader of the Labour Party, then in receipt of a salary in the region of €200k per annum, which just goes to confirm the absurdity of Irish politics.

Yet we cannot insist that all Lefties are equally bereft of integrity. Socialist TDs Joe Higgins and Clare Daly, were jailed for protesting against bin charges in 2003. Higgins subsisted on half his salary, donating the remainder to his party. TD’s under the banner of ‘People before Profit’ can claim a similar ideological legitimacy.

Perhaps there is some cut off point at the lower middle class, where the legitimacy of being a Lefty starts to break down? Lefties (real ones) apparently don’t drive Range Rovers, or have islands in their kitchens, and they don’t live in the leafy burbs.

Yet I, along with many family members and a few friends who are relatively wealthy, consider ourselves ‘legitimate’ Lefties. The real test arrives when we are called upon to give some of it back, to pay more taxes, or take pay cuts. I like to think that we would gladly rise to the occasion. However, I am yet to experience a political regime that is willing to lead by example, and until then, my own superfluous wealth is safe from them, and perhaps safe from a more honest version of myself.

Protective Rationalization

The chaplain had sinned, and it was good. Common sense told him that telling lies and defecting from duty were sins. On the other hand, everyone knew that sin was evil and that no good could come from evil. But he did feel good; he felt positively marvellous. Consequently, it followed logically that telling lies and defecting from duty could not be sins.

“The chaplain had mastered, in a moment of divine intuition, the handy technique of protective rationalization, and he was exhilarated by the discovery. It was miraculous.

“It was almost no trick at all, he saw, to turn vice into virtue, slander into truth, impotence into abstinence, arrogance into humility, plunder into philanthropy, thievery into honour, blasphemy into wisdom, brutality into patriotism, and sadism into justice. Anybody could do it; it required no brains at all. It merely required no character.

Joseph Heller, Catch-22 (1961)

In many respects a new market space has opened up where Lefties can now outsource our morality, in order to reconcile private wealth with the realities of global, ecological and home-grown privations.

In pursuit of this ‘protective rationalization’ the easiest thing may simply be to deny everything, from climate change to the Holocaust. To blame the poor for poverty and the addict for his addiction – de-legitimizing the left by pointing to their expensive phones.

Having lived in California for many years and been educated there, I wonder at how I reconciled my own life; going to college, driving a pick-up, living in a comfortable apartment in Sacramento, and attending University. How was I able to reconcile my hard-earned comforts with the privations I witnessed while walking through the Mission District? There one encounters a kind of ‘zombie apocalypse’ – an army of homeless, social outcasts, mentally ill, war-veterans, alcoholics, drug addicts, down and outs, panhandling to get by, engaging in petty crime, sleeping on the streets, and being a veritable ‘nuisance’ to all and sundry.

At the time, I bought into a particular narrative that may have held an element of truth back in the naughties. I had emigrated to America with nothing, I had some help from a girlfriend. I lived with her until I could get on my own two feet; obtained a student visa to make myself legitimate; attended college; found a job and secured a credit card.

Encountering the homeless, I too saw them as ‘bums’ and ‘wasters’:too fucked up on drugs; or too lazy to take advantage of the opportunities that California had afforded me. They may not have had expensive phones but they had the same ‘opportunities’ as I enjoyed.

Since then I have grown up, and become a little wiser in respect of what ‘causes’ another human being to sleep on the streets. Yet, what I now know remains alien to many Americans who cling to the belief that their nation is a ‘frontier’ society, where fortune and success await anyone willing to get out of bed early in the morning and get to work.

Henry David Thoreau

Henry David Thoreau

I imagine that when Henry David Thoreau began his life experiment on Walden Pond, his ideas conformed with those of a contemporary Republican in the U.S., Indeed, his assertion that ‘government is best which governs least’ remains a Republican or Right-wing ideal, in respect of taxes and social investment.

If, however, that assertion is amended slightly to: ‘government is best which has to govern least’, we may gain a clearer understanding of what Thoreau stood for. There is an obligation upon government to govern, and there is an equal obligation upon individuals members of society to avoid needing an excess of governance.

Society requires a government to keep us safe from criminals; to protect borders from invasion, (armed as opposed to invasions of the hungry or displaced); to treat its water and sewage; to tend to the sick and to educate children.

Government on all these levels is essential. Yet there is a vital counterbalance to the need for government. This arises from the autonomy of the individual, his freedom to determine his own destiny. If we convince ourselves that the bum has chosen his destiny and that his choice is his ‘right’, his ‘freedom’; we find it easier to exclude the horror of his existence from the relative comforts of our own lives.

But it isn’t easy to convince oneself that another human being deserves a squalid life, simply because of a ‘choice’ he has made as an expression of his liberty. Yet this is an approach that seems to work for a lot of people.

So what can we do? We can’t simply raise enough in taxation to provide every homeless person in the Western world with a slice of middle class living.

Perhaps we can stay on track, with the Republican notion of ‘opportunities’, so that the poor have less of an ‘excuse’ to be poor? Wherever that argument lead us, it cannot escape the hard reality that fellow human beings should not be allowed to sleep, live and die on the streets. Nor can it escape the reality that the existence of winners gives rise to losers. Clean, hygienic shelters/homes, access to adequate nutrition, to mental health services, to education; all are eminently realisable in a state that can send aircraft carriers to the Persian Gulf.

A rejection of personal material wealth raises a different type of intellectual ‘poverty’ and affords us a different type of environmental solution. In respect of the environment, and our own personal ‘enlightenment’, it might well be the only approach that will permit the global human enterprise to continue.

Love thy Neighbour?

So the Lefty question remains: Is it wrong for me to live out a life of comfort, whilst many within my society and billions outside of it, live in squalor or at least as ‘losers’ beyond the prevailing notions of success? I fear the answer is yes. But at what distance does my relative abundance, my moral indignation, my personal wealth, become relatively immoral? Perhaps I owe more of an obligation to my immediate neighbour, if indeed I am aware that he or she is hungry or suffering or is abusing his dependents. But what if he lives two doors down, or a block away, just across the border, or on another continent?

Sadly, as we become wealthier, we become less overtly Lefty. We subtly change our morals to accommodate our ‘success’ in the world. As the process evolves we become overburdened by our possessions, our connections with corporations, or our smartphones. The weight often grows to the extent that we feel a need to outsource those same morals, to a ‘safer’ place than Leftist activism.

We achieve this through comedy, through the arts, or perhaps through supporting the Green Party. Art allows us to feel the pain of the poor without getting our hands dirty. Comedy provides us with a safety valve to laugh at the pointless nature of our own materialism, our insatiable desire for more of the same.

The Green Party are of course not the enemy. Yet the notion that we can ameliorate the collapse of global ecology, through a new type of ‘Green consumption’, through recycling, or by driving an electric car is a palpable manifestation of our capacity for delusions that are at once essential and ineffectual.

The Growth Illusion

The poverty that is chiefly described in the West, is rarely the real poverty that sleeps on the streets and numbs itself with heroin. It is instead, the self-absorbed horror show of ‘relative poverty’; doctors, teachers, nurses, state employees, train drivers, taxi men, all of us feeling that relative to others, we don’t earn enough and don’t possess enough.

The desires of the ‘many’ are the voices that politicians listen to. Putting more money in the pockets of ‘ordinary people’ or ‘the squeezed middle’, is the mantra of almost all political parties. It is the basic economic imperative of the state. It grounds what Richard Douthwaite and others have referred to as the ‘The Growth iIlussion.’ Growth maintains the irony that a cure for our social and environmental ills, can only arise from more of the same cancer.

In Walden Pond, Thoreau made an honest evaluation of our real needs by his little experiment in the woods. He added the corollary of an extended list of things that are honestly beautiful, and of value. Unsurprisingly most of these things cost nothing at all.

I see young men, my townsmen, whose misfortune it is to have inherited farms, houses, barns, cattle, and farming tools; for these are more easily acquired than got rid of. Better if they had been born in the open pasture and suckled by a wolf, that they might have seen with clearer eyes what field they were called to labor in. Who made them serfs of the soil?

Why should they eat their sixty acres, when man is condemned to eat only his peck of dirt? Why should they begin digging their graves as soon as they are born? They have got to live a man’s life, pushing all these things before them, and get on well as they can. How many a poor immortal soul have I met well-nigh crushed and smothered under its load.

The Left is Dead, Long Live the Left

We have murdered the Left by failing to recognize that we ourselves, our individualism and materialism, remain the absolute source of our social ills, and petty dissatisfactions.

The revolution cannot begin until we reject materialism in ourselves, the devil at home as opposed to elsewhere. We must become proud to be materially poorer than our neighbours, so that we might be richer; in spirit, in mind, in temporal freedoms, in Nature and in soul. What a truly paradoxical concept! The only thing such an idea has going for it, is the fact that today more than ever before, this is as realizable as it appears impossible.

Plato in his idealised Republic insisted that the political elite of his ideal state, its ‘Guardians’ should not be paid, and should treat gold as if it caused a disease. They would be trained to recognize that their gold lay in their souls and cultivated minds.

James Joyce described his art in A Portrait of Artist of a Young Man as follows: ‘I go to encounter for the millionth time the reality of experience, and to forge in the smithy of my soul the un-created conscience of my race.’ That aspiration should become the banner of an honest version of the Left.

When Ireland or indeed any wealthy country begins to see politicians rejecting their current salaries in favour of a minimum wage, once more copies of Ulysses instead of Argos or Ikea catalogues adorn coffee tables; when we we begin cultivating our gardens, baking bread, and leading by example; only then will the Left be a living honest thing. Then a revolution will have begun; not out the streets at the behest of social media, but rather within, the ‘smithy of the soul.’

Perhaps there is something in the phrase that; ‘there is good in everyone’. Alas, I have my doubts. But it is this ‘good’ that demands practical and honest expression from the top down. It is then that the environment will have a hope, and the plutocrats will have something to fear. Then and only then will the cause and need for socialist charity begin to end. Governments will need to govern less. The Left will be ‘woke’, and the tired old game will have been irrevocably changed.