On the April 13 2024, a man stabbed several people in a shopping centre in Sydney. The morning after, I was walking past the Four Courts in Dublin, when a man approached me making a stabbing motion in the air. I fixed my eyes on him as my heart sped up, but it stopped as quickly as it started. Just a gesture of three or four stabs. I saw there was nothing in his hands, but kept my distance as he passed. He didn’t make eye contact or acknowledge me.

The experience threw me off kilter. For a second I doubted what I’d seen. Why would someone do that? To scare people? But he didn’t even seem to notice me. Was he on the phone, and accompanying his words with thoughtless gestures, inconsiderate of how it might affect passers by? Or was he lost in his thoughts, unaware of the world, and acting out some inner drama? Safe to say, I looked over my shoulder a few times as I walked on.

The problem of violence, such as the Sydney stabbing, or the shocking attack on Dublin’s Parnell Square last year, involves many factors: trauma, mental illness, addiction, social isolation, inequality… We could pull on any thread and find enough material to make a case for its importance in contributing to such acts.

For the mainstream media and politicians, however, explanations are simple. These people are “thugs“, “hoodlums“, “scumbags“. Anyone questioning the role society plays may be accused of giving criminals a free pass, and not holding them accountable for their actions.

After violent attacks like the ones mentioned, the media is normally quick to assure people that the motivation was not “terrorism”. The distinction seems to be this: terrorism is motivated by an ideology, a political position. A terrorist act has meaning. But these other types of attacks, according to the mainstream, have no meaning. The attacker was “schizophrenic”, homeless, jobless. Therefore, the violence has no sense to it. It is merely an outburst of animal savagery into the pure, clean, bright and ordered streets. The blame does not lie in us, but in them – those who cannot raise themselves up high enough to walk among us in our enlightened ways.

Violence is like a volcanic eruption. It comes from the lower, subterranean levels of the social body. And we happily ignore the tectonic pressures that are pressing down on those in the depths.

Within and Without

How long before supermarkets are only accessible to those who can prove their bourgeois status?

“QR codes at the ready, please.”

Matthew struggled to hold his phone steady as the guard scanned the QR.

“Let us see here…” said the guard, reviewing Matthew’s data. “An annual income of sixty thousand a year… Very good sir, go right ahead.”

Minister for Justice McEntee’s vision for the future of public safety paves the way admirably for such a future, with her proposals including mass surveillance with Garda body cameras, CCTV, EU-wide biometric databases, and Facial Recognition Technology (FRT). To quote from Deleuze’s prescient ‘Postscript on the Societies of Control’:

Felix Guattari has imagined a city where one would be able to leave one’s apartment, one’s street, one’s neighbourhood, thanks to one’s (dividual) electronic card that raises a given barrier; but the card could just as easily be rejected on a given day or between certain hours; what counts is not the barrier but the computer that tracks each person’s position — licit or illicit — and effects a universal modulation.

Our smartphones would be easily integrated into such a system. We could implement it in an afternoon. Of course, some people will complain of the undemocratic aesthetic of such a system, but then when they read the news reports about stabbings, and think of the children, they will put aside their misgivings and gladly walk through the sliding doors with the rest of us. Most of us conformed to a similar QR code system during the pandemic in the name of the public good.

Instead of radical change, society is on track for a compromise. Instead of asking ourselves why our society causes so much illness, loneliness and violence, we are resolving to create stronger walls between us.

Europe is already a fortress, a walled garden in the memorable words of Josep Borrell, the EU’s foreign policy chief. Our world is divided into the lucky few within, and the unlucky masses without. This dichotomy reaches its most absurd form in Gaza, where enemies at Israel’s gate are not outside, but themselves walled in, a city under siege, enclosed by blockades and checkpoint borders, barraged by missiles.

Image: Daniele Idini.

Golden Tickets

Western society dangles two tickets into the middle class before the labour force: inheritance and hard work. For many people, however, even the second option is becoming unfeasible. The ladder is being pulled up, and the majority of young people now worry they are going to be left behind.

Let us step past, however, the despair of the downwardly-mobile middle class, of which much has been already written. What are we to do with those who cannot meet the demands of middle class careerism? If you can’t manage your addictive behaviours (after all, we are all addicts, in one way or another), and you can’t navigate the world of work, what happens to you?

Those who cannot work are directed to a world of rules, appointments, documents, waiting rooms, lines, interviews, and regular check-ins.

But what if you don’t have a fixed address? And what if you don’t have a mobile phone? Or what if you can’t keep track of all these requirements?

If you fail to navigate the Kafkaesque world of bureaucracy, then you have the final frontier; a Diogenes-like existence at street corners, hostels, and cardboard windbreaks. Soup outside the GPO. Spare change. Random assaults by drunken louts who take middle-class disdain for you as permission to inflict pain.

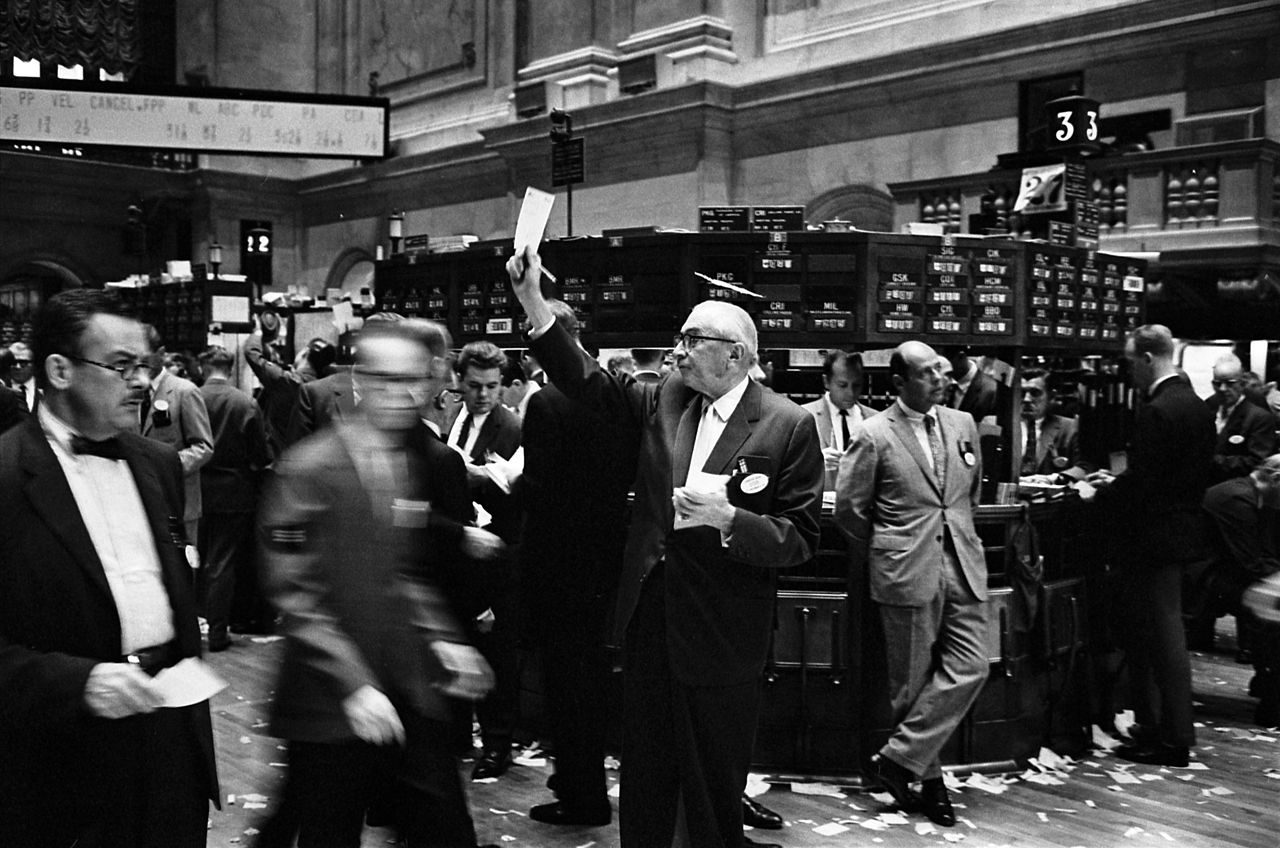

Stockbrokers, New York, 1966 from United States Library of Congress‘s Prints and Photographs division under the digital ID ppmsca.03199.

A Successful Civilisation

Historically speaking, our civilisation has arrived at a point of absurd wealth. Through industry, the machine, the market, automation, and the outsourcing of backbreaking work to countries with conveniently lax labour laws, we have access to luxuries unimaginable to a mediaeval king. According to the British Fashion Council, we have enough clothes to dress the world for the next six generations. According to the UN, we can feed everybody on the planet. Why then, do we insist on bestowing the fruits of collective human achievement only to those who pass the test of ‘functioning’ in an insane society?

This hyper complex informational administrative “service” economy is historically unprecedented. And yet we expect everybody to pick up the skills necessary to thrive in it, or we punish them brutally and unsympathetically. We see it as a bare minimum achievement to survive in this strange environment and punish those who can’t live like us with alienation, hunger, and hardship.

In 2013, eight million 5-centime coins (one per inhabitant) were dumped on the Bundesplatz in Bern to support the 2016 Swiss referendum for a basic income (which was rejected 77%–23%).

The Case for Universal Basic Income

I am a proponent of Universal Basic Income (UBI). The idea is simple: give everybody enough money for clothes, food and shelter. The income is different from the dole. Everybody gets it, even if they don’t need it. There’s no need to endure intrusive bureaucratic nosing into how you spend your time in order to qualify for it.

Most of us dismiss UBI out of hand. But why? Do we fear that a life of safety, satiety and comfort will make us lazy, debased, selfish creatures? It appears to me our current system does a fine enough job at that. If anything, UBI would do the opposite. It would improve morality, because it’s easy to be generous and patient when you are well-fed and comfortable.

But for all you cynics, to whom I sympathise, let’s put aside the appeal to morality and ask this: Do you really think a basic lifestyle of security and comfort would be enough for most people? I think many people would work simply so they can show off their wealth to others, without needing to be incentivised by fear of ruin. As social animals, our need for status is deeply felt. People will work to signal their vigour, or simply as a way to pass the time and give their life a sense of purpose and meaning.

And what about jobs that nobody would do for free? At the moment, these are the lowest paying jobs in our economy. We expect the people with the fewest opportunities to resort to them – essentially a kind of slavery. In a better society, the most unpleasant jobs, like cleaning the toilets, would be the best paid. Or maybe we can just build some robots to do that, rather than building robots to make music and art – you know, the stuff that humans actually like doing.

Anyway, what’s the big deal if people become idle? Let them go for it. Idleness is certainly less harmful than most of the activity that goes on in our civilisation, and earns applause, billions of euros, and occasionally Nobel Peace Prizes.

Fin Divilly – Songwriter and Performer by Daniele Idini.

Not just for Artists

UBI was trialed in Ireland, in a flawed manner, via the Basic Income for the Arts (BIA) pilot scheme, which closed in 2022. As the name suggests, a basic income was extended to artists alone. To me, this runs contrary to the most important part of Universal Basic Income: its universality. You shouldn’t need to prove that you are already providing a service to society in order to qualify for it. That’s putting the cart before the horse. UBI is meant to free up people so they can begin to do more valuable things with their time, which should be valuable to society too.

By granting it only to a certain category of people, it implied that the income was a conditional grant, rather than an unconditional gift. It came across as a transparent deal: we’ll give you money, but we want you to create commodities in return. Rather than challenge the logic of capitalism, opening the way for a new kind of society, it reinforced the existing system.

I understand that artists were impacted badly by the pandemic, but so were homemakers and carers – are they contributing less to society than professional artists? UBI should be a no-strings-attached gift given in good faith to everybody, not a conditional grant for a cohort of well-respected creatives.

The flawed thinking behind the BIA scheme was so effective at poisoning the well, and confusing people about the potential of UBI, that it almost feels intentional. A better trial would involve a completely fair lottery, with the name of everyone in the country in the pot. That way, we could see the impact of receiving a UBI on the lives of people from a cross section of Irish society, and all types of socioeconomic backgrounds.

A lot of people today are stuck doing work they know is meaningless, simply because it pays the bills. The technical term for such an employment, as coined by the late David Graeber, is a “bullshit job”. Far from being a ticket to freedom, bullshit jobs induce a feeling of guilt, low self-worth, and absurdity. Most of us have ideas of what we would like to do if we had more time, if we weren’t constrained by the necessities of earning money for rent, food, and utilities. Ultimately, we are kept in place by a sensation of insecurity. Imagine what we could do if our lives weren’t based on fear.

Feature Image: Daniele Idini