To understand the origins of the Irish Housing Crisis we also need to look beyond our shores, and excavate the substrate of the modern global financial order. This will reveal a slow journey towards the neoliberal financialisation of property as an asset today – overwhelmingly bought and sold regardless of the needs of society at large. Today, individuals act as private companies, but invariably lose out to better organised and resourced institutions, while the periodic burstings of speculative bubbles widen inequalities, and create conditions for Populist uprisings.

The land question has haunted Irish politics since time immemorial. Frank Armstrong attributes the current acute housing crisis to the colonial settlement.https://t.co/7Qp4K5wQrr@broadsheet_ie @BowesChay @vincentbrowne @connolly16frank @caulmick @RoryHearne @fallon_donal

— CassandraVoices (@VoicesCassandra) August 17, 2021

In particular, it should be recognised that our capitalist system is not simply a market economy, of which there have been numerous variants through history, none of which, including our own, truly “free” in any meaningful sense. Capitalism in its current guise exhibits a dispassionate face, but ultimately relies on violent enforcement of interest-bearing loans by officers of the State. It arrived in the wake of widespread acceptance of what was previously considered the sin of usury – the practice of making unethical or immoral monetary loans that unfairly enrich the lender – by Protestant reformers during the Reformation.

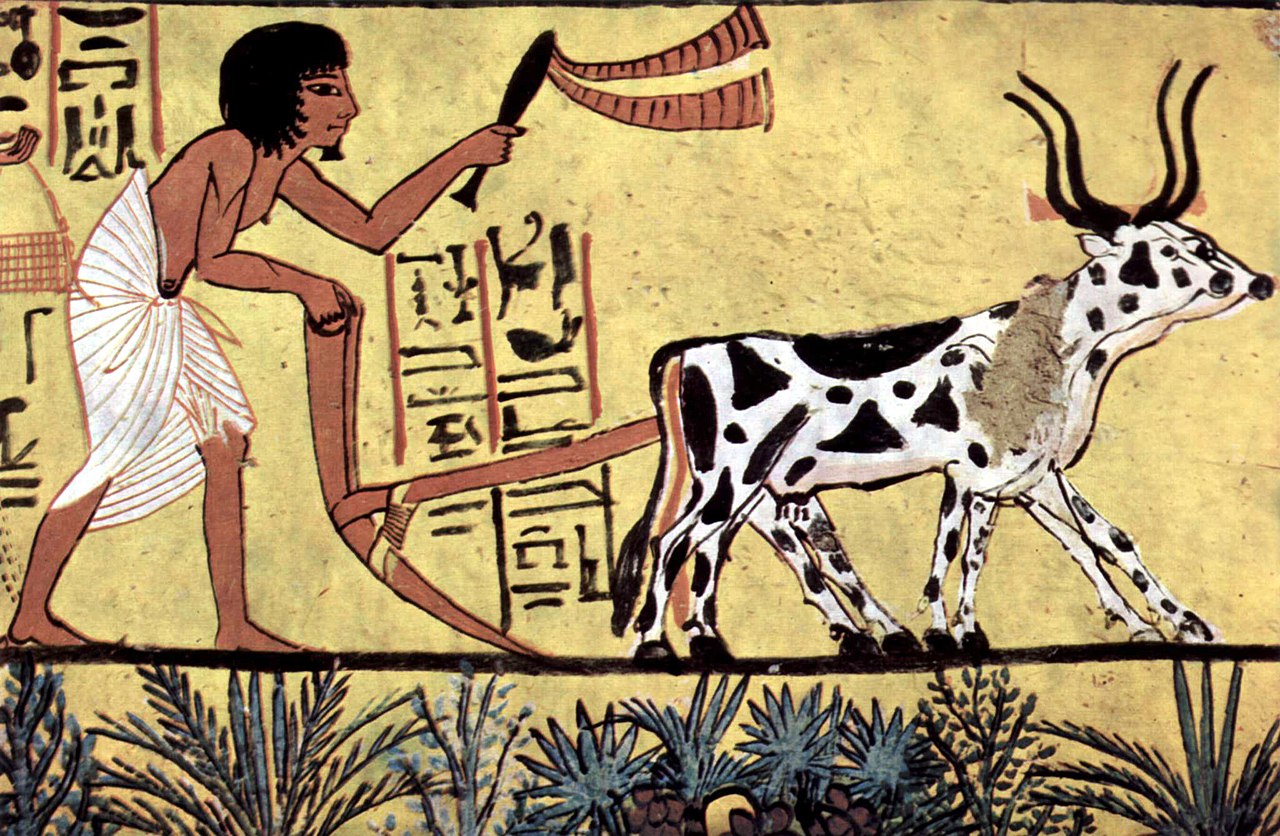

Markets in goods and services have existed since civilisations first emerged in the Middle East, but these were invariably softened by community solidarity, wherein laws and norms ensured trade was not conducted – as we see increasingly today – as an impersonal, zero-sum game between competing parties. Of course, there were various categories of people – including women and slaves – that were excluded from such commonwealths, nonetheless a sense of mutual obligation and reciprocity was more pronounced in the trading arrangements of pre-modern polities.

It is only in recent history, as living standards have risen through technological advances, enhanced food supply and sanitation – along with the arrival of various forms of income redistribution associated with the welfare state – that property – in material terms shelter – has emerged as central to the achievement of a basic standard of living, and the good life we now expect. Its acquisition has become an all-consuming preoccupation in many countries, Ireland not least.

Subsistence Level

Even in Europe and North America, until the twentieth century the primary challenge for most families was to obtain sufficient food for survival. Due in part to a veneration of an economic philosophy of laissez faire, associated with Adam Smith, ample sufficiency was slow in arriving, despite increased supplies arising out of the Second Agricultural Revolution from the seventeenth century onwards; along with the arrival of subsistence crops from the Americas, including our beloved potato, and maize.

In Europe, initially at least, the ascent of the bourgeois from the seventeenth century worked to the detriment of peasants and a new working class. Thus, despite technological developments, such as the invention in Europe of the printing press, and a more stable food supply in the years between 1500-1650 prices rose by 500%, but wages rose much more slowly.

There were continuous interruptions to, and distortions of, food supply in a nascent capitalist market. The beginning of the seventeenth century witnessed grain surpluses in England as agricultural capacity exceeded the requirements of the population. Carryover inventories of food averaged between 33 and 42 percent of annual consumption. Therefore, in that period: ‘famines were man-made rather than natural disasters.’[i]

The typical English subsistence crisis after the ascendancy of Henry VIII did not take place because of insufficiency but because ‘the demand for inventories pushed prices so high that labourers lacked the cash to purchase grain.’ In essence, merchants were hording, and the poor were starving.

The Procession Picture, c. 1600, showing Elizabeth I borne along by her courtiers.

During the late Tudor period ‘paternalistic’ authorities recognised this and acquired surpluses, selling it on at prices affordable to the lower echelons of society, much to the annoyance of millers, brewers and bakers. That progressive market intervention unravelled during the Civil War of the 1640s, when Roundhead mercantile interests began to exert authority over government decision-making.

It was only in the 1750s, in the wake of food riots of ‘unprecedented scope’, that the State began to subsidise grain once again. As a result, by the early nineteenth century, famines had been conquered in England ‘not because the weather had shifted, or because of improvements in technology, but because government policy… had unalterably shifted.’[ii] Sadly that policy did not extend to Ireland.

Today, in order to achieve social harmony it seems likely that governments, including the Irish, will have to treat property as an essential commodity, similar to food, wresting control from a system that has enshrined the gambler.

Sealing of the Bank of England Charter (1694), by Lady Jane Lindsay, 1905

Bank of England

In the U.K. a financial system emerged associated with the creation of the Bank of England in 1693, when a consortium of bankers made a loan of £1,200,000 to the king. ‘In return’, according to David Graeber, ‘they received a royal monopoly on the issuance of banknotes … a right to advance IOUs for a portion of the money the king owed.’[iii]

A system of credit enforced by military might went global during the colonial era, leading to the enrichment of a class of financiers operating out of the city of London in particular. Fernand Braudel characterises this form of capitalism as first and foremost the art of using money to get more money.[iv] The capacities of this system appear to have reached a perfect pitch in our contemporary era.

But what system preceded this? And could there be an alternative? Prior to the arrival of paper money IOUs issued by the Bank of England, below the surface, older market systems based on mutual trust and solidarity operated. These were overwhelmed by the impersonal calculation that continues to characterise financial services, underpinned by the violent capacity of the State.

Thus David Graeber observes: ‘Under the newly emerging capitalist order, the logic of money was granted autonomy; political and military power were then gradually reorganized around it.’[v]

In his indispensable A History of Debt: The First 5000 Years, Graeber argues the ‘great untold story of our current age’ is of the destruction of an ancient credit system found in small towns and villages across England, and beyond. This was a complex market based not on coins, but on trust. In a typical English village: ‘the only people likely to pay cash were passing travellers, and those considered riff-raff.’ Reveallingly, he observes that ‘just about everyone was creditor and debtor’ and that ‘every six months there would be a public reckoning’ when the community would resolve their debts to one another based on a person’s ability to pay.[vi]

Such a system reflects a passage in the New Testament (Matthew 20:1-16) in which a landowner pays workers the same sum at the end of the day despite each one working different hours. When one of the workers complains the landowner responds:

‘I am not being unfair to you, friend. Didn’t you agree to work for a denarius? Take your pay and go. I want to give the one who was hired last the same as I gave you. Don’t I have the right to do what I want with my own money? Or are you envious because I am generous?’

So the last will be first, and the first will be last.

In any community there are those less fortunate than others, and a pre-capitalist system of resolving debt, and rewarding work, acted as an impediment to excessive accumulation of resources in a few hands. Importantly it was not simply barter, as value was ascribed based on an ability to pay, and material needs, as much as on the labour or other input into the good or service. A cobbler might therefore produce shoes for an impoverished widow at a lower price than that set for a prosperous miller. No doubt it wasn’t idyllic, but it seems to have led to a fairer and more harmonious existence than what followed in its wake.

Graeber argues that ‘this upsets our assumptions [as]we are used to blaming the rise of capitalism on something vaguely called the market’, but these ‘English villages appear to have seen no contradiction between the two.’[vii]

John Constable – Parham Mill, Gillingham.

Money was Trust

In this world trust was everything: ‘Money literally was trust.’ Neighbours appeared he says ‘quite comfortable with the idea of buying and selling, or even with market fluctuations, provided they didn’t get to the point of threatening poorest families’ livelihoods.’ Thus Graeber describes the origin of capitalism as ‘the story of how an economy of credit was converted into an economy of interest.’

The new legal order of strictly enforceable loans had serious consequences for debtors, a position which was connected to sinfulness, and led to imprisonment. Graeber goes so far as to argue that this amounted to ‘the criminalization of the very basis of human society. It cannot be overemphasised that in a small community, everyone normally was both lender and borrower.’

He also argued that this transition provided ample space for swindlers and cheats:

What seems to have happened is that, once credit became unlatched from real relations of trust between individuals … it became apparent that money could, in effect, be produced simply by saying it was there, but when this was done in … a competitive market place, it would almost inevitably lead to scams … causing the guardians of the system to periodically panic and seek new ways to latch the value of the various forms of paper onto gold and silver.

Moreover:

Only the wealthy were insulated, since they were able to take advantage of the new credit money, trading back and forth portions of the king’s debt in the form of banknotes.[viii]

Eventually the price of bank notes stabilized once notes became redeemable in precious metal. This is referred to as the Gold Standard, which emerged following the South Sea Bubble Crash of 1720. But this crash was far from the last in what appears an inherently unstable system. As Graeber puts it: ‘it does seem strange that capitalism feels the constant need to imagine, or to actually manufacture, the means of its own imminent extinction.’[ix]

Hogarthian image of the 1720 “South Sea Bubble” from the mid-19th century, by Edward Matthew Ward.

Separate Legal Personality

Companies were established in canon law by Pope Innocent IV in 1250, and applied to monasteries, churches, guilds and other institutions, but were in no sense profit-seeking enterprises in the modern sense. However, according to David Graeber ‘once companies’, such as the East Indian Company, ‘began to engage in armed ventures overseas … a new era in history might be said to have begun.’[x]

The inherent danger of profit-seeking corporations was once widely recognised. Thus, between 1720 and 1825 it was a criminal offence to start a company in England, during a period of rapid economic expansion.

In the United States until the nineteenth century there were two competing ideas regarding the purpose of companies: the first involved those with charters restricted to the pursuit of objectives in the public interest, such as canal building; the other regime issued charters of a general character, allowing companies to engage in whatever business proved profitable.[xi]

The latter category emerged triumphant, divorced from responsibility to fellow citizens; an unaccountable abstraction with separate legal personality established in the landmark 1897 case of Salomon v. Salomon. Thus capitalism discovered the perfect vehicle for wealth accumulation, and as wealth begets wealth, increasingly multinational companies overwhelmed smaller family-owned businesses as a wander down any high street today confirms.

Moreover, as corporations have swelled in size, a chasm has opened up between the pay levels of senior officers and rank and file workers. Thus, whereas in the 1950s the CEO of General Motors, then the model of a successful US business, was paid 135 times more than assembly-line workers, fifty years later the CEO of Walmart earned as much as 1,500 times as much as an ordinary employee.

Moreover, according to Theodore Zeldin: ‘In the twentieth century, the British colonial empire was replaced with a less visible but even more powerful financial empire compose of an archipelago of some sixty offshore tax havens presided over by the City of London.’[xii]

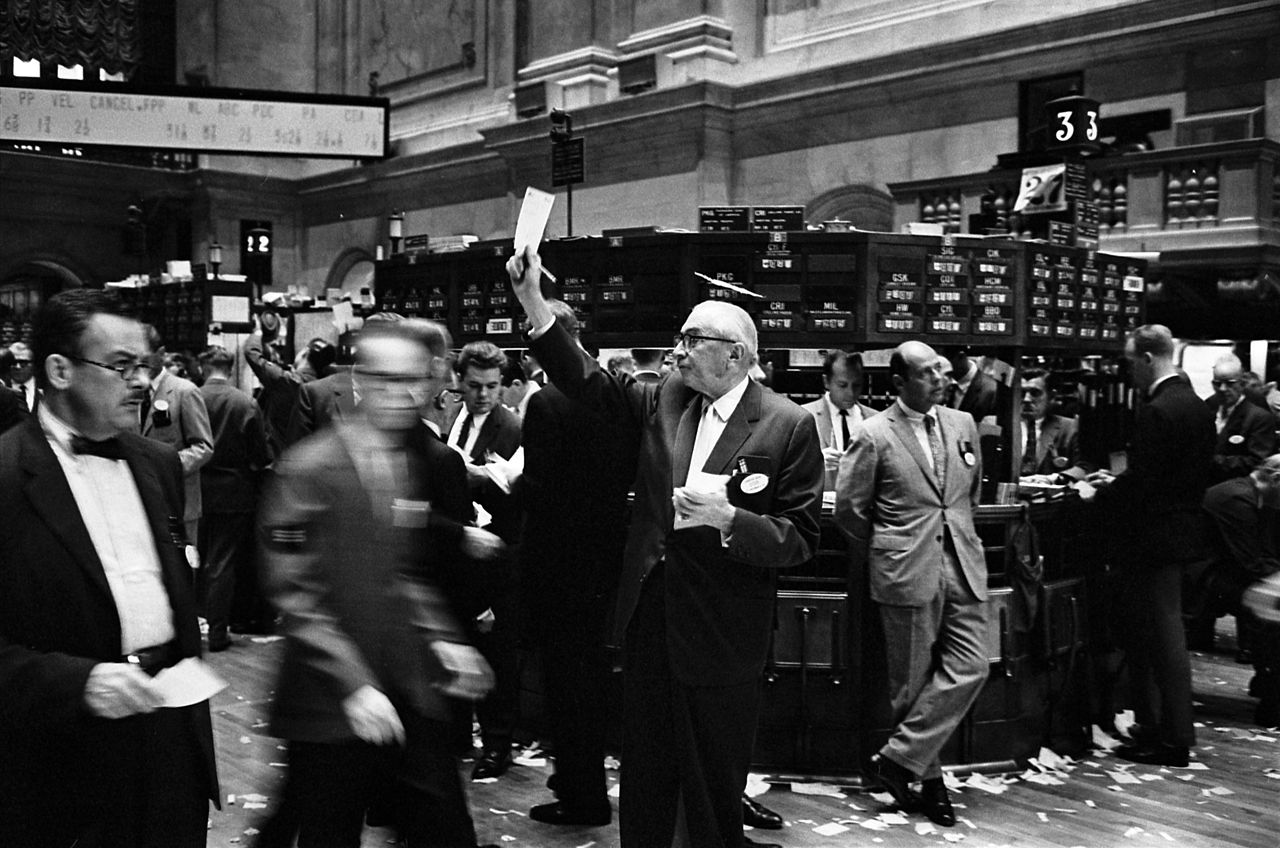

As companies grow in size and internationalize, the pursuit of profit becomes an overriding purpose, and the connection between management and workers diminishes to a point where companies are no longer embedded in communities. This is particularly evident in financial services, where making money out of money has become a conjuror’s act, increasingly incomprehensible to the uninitated. It was surely only a matter of time before property would be adopted as a speculative asset to an all-consuming leviathan.

Property Today

For obvious reasons, throughout history land has been a paramount concern for peasant societies, primarily as a source of food, grown for subsistence and as a commodity. Agricultural land, however, must be worked, so speculation in rural land produces scant reward unless there is skilled labour and capital attached. A surviving aristocracy has continued to draw incomes from rural rents, but this has been severely dented by agrarian movements that emerged in Ireland and elsewhere to produce a class of petit bourgeois peasant proprietors.

Similarly, at least until the end of World War II, in urban areas property brought significant trouble and relatively scant reward for any landlord, with tenancy considered a transitory existence associated with student years; while public housing schemes assisted the urban poor to leave tenement dwellings that had bedevilled many cities, including Dublin, which had the worst housing conditions of any city in the United Kingdom at the turn of the last century.

However, since the post-War period workers, including those engaged in monotonous ‘unskilled’ work, joined forces to win a series of improvements to their conditions. These included a five-day week and eight-hour working day, along with aspirations to a living wage. It allowed scope for many, if not most, of those pointedly referred to as ‘the working class’ to enjoy a reasonable, and improving, standard of living across the Western world. Importantly, a steady job permitted home ownership.

Moreover, in the wake of the so-called Green Revolution in agriculture after World War II – which led to a radical reduction in the cost of food – steadily rising living standards in the U.S and Europe brought a profusion of recreational activities including sports, and unprecedented access to the arts, especially film – the defining cultural form of the twentieth century – along with access to higher education, even for the children of the poor. In these circumstances property became an increasingly prized asset – pent-up demand ripe for exploitation if circumstances permitted.

Crucially, from the 1970s, an ascendent neoliberalism led to governments around the world withdrawing from the housing market, leading to dramatic decreases in the stock of social housing. In 2015 in Ireland, for example, by which time economic growth for the year was at 7.8%, a mere 334 social and affordable units were built.[xiii]

In the meantime, regular stock market crashes underline to financiers the reliabiity of bricks and mortar as an investment. Pension funds especially relish the assured income that property generates. Thus, even when there is a crash in property prices, as in Ireland, rents continue to be paid, and with assistance from the State – socialism for the rich – property prices rise once again.

Throughout most of history the quest for a crust of bread has been the dominant struggle for the bulk of humanity. Today, in the Western world at least, somewhere to rest one’s head in a place of one’s own has become the overriding concern. At the heart of the housing crisis in Ireland, and elsewhere, lies a yearning for the good life that most us see as a right, but which is being exploited by a buccaneering class of financiers, many of whom survived the Crash of 2008, and continue to exert control over the institutions of the Irish state.

It appears that just as governments had to regulate food supplies in order to avert famines and accelerate development in the early modern period, similarly today it has become necessary for states, especially the Irish State, to regulate a property market which is working to the detriment of a growing proportion of the population. More generally, whether we can do away with the rigidity of a capitalist system of debt enforcement, and return to a market based on greater social solidarity and reiprocity remains to be seen. But at least we should radically reform an inherently unstable and unfair housing market, which is failing to deliver the good life we have a right to expect.

[i] Roderick Floud, Robert W. Fogel, Bernard Harris, Sok Chul Hong, The Changing Body: Health, Nutrition, and Human Development in the Western World since 1700, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2011, p.116

[ii] Floud et al, pp.117-118

[iii] David Greaber, Debt: The First 5,000 Years, Melville House, London, 2011, p.49

[iv] Immanuel Wallerstein, ‘Braudel on Capitalism, or Everything Upside Down’ The Journal of Modern History Vol. 63, No. 2, A Special Issue on Modern France (Jun., 1991), pp. 354-361 (8 pages) Published By: The University of Chicago Press.

[v] Graeber, 2011, p.321

[vi] Graeber, 2011, p.327

[vii] Greaber, 2011, 327

[viii] Graeber, 2011, pp.328-341

[ix] Graeber, p.360

[x] Graeber, p.305

[xi] Theodore Zeldin, The Hidden Pleasures of Everyday Life. A new Way of Remembering the Past and Imagining the Future, Maclehorse Press, Quercus, London 2015 pp.232-233

[xii] Zeldin, 2015, p.109

[xiii] Dan MacGuill, ‘FactCheck: How many social housing units were actually built last year?’, 9th of February, 2016, www.thejournal.ie, https://www.thejournal.ie/ge16-fact-check-election-2016-ireland-social-housing-2587923-Feb2016/