No picture of the modern world is complete without a Marxist analysis. The fundamental point – even for anyone who is not a fellow traveller – is that a materialist analysis of capitalism’s inherent instability is essentially correct, and now more relevant than ever.

The problem has always been around how a post-capitalist society emerges without savage bloodletting and numbing totalitarianism. The bearded figure scribbling away in the British Museum would no doubt have been horrified by the barbarous regimes – from Lenin to Kim Jong-Il – that have laid claim to his legacy.

Slavoj Žižek is perhaps the best known representative and synthesiser of contemporary Marxist theory. Anyone who has viewed his films The Pervert’s Guide to Ideology (2009) or The Pervert’s Guide to Cinema (2012) can only marvel at how this middle-aged, slovenly Slovenian Marxist is taken so seriously. Despite the spittle that pours involuntarily out of his mouth as he expostulates, it seems his ideas are judged on merit; albeit a somewhat comedic appearance has probably made him seem less of a ‘danger’ – especially when set against a straight-backed sparring partner such as Jordan Peterson – and ‘Ted-Talkily’ acceptable.

Žižek is a complex political thinker, noted for his observations on ideology. Yet his writing is dense, often impenetrable, and even, at times, frankly nonsensical. Sadly, the content can be obscure, and the ideas often wildly over-stated, though recent books have seen him curb this tendency, leading to greater traction. With age he has mellowed, or at least he has become far more coherent in his critique of the late capitalism disaster movie unfolding before our eyes.

His thought processes are, nevertheless, eminently contestable. Former Irish President Mary McAleese – who lectured me – always despised recklessness, as do I, but in a different sense. It is intellectual recklessness I hold in low regard. Žižek is full of it, at least in terms of his wilder statements calling for insurrection.

Žižek argues that the widespread belief that our world is post-ideological is an ‘arch-ideological’ fantasy. Today, he asserts, ideology entails what people impute to others, whether left or right.

This demonization of others, and the exclusion of outsiders, is indeed very much to the fore in his recent writings, and in our end of day’s capitalist order. Tribalism, nationalism and the targeting of non-nationals and immigrants is an endemic feature of our time.

For a subject to adhere to an ideology he argues, he must have been presented with it, and accepted it as true and right – such that anyone sensible should believe in it. In a seminal text, The Sublime Object of Ideology (1989) Žižek claims that ideology has not disappeared, but has come into its own, and because of its success, it has been dismissed as non-existent. Or should it be that ideology has been internalised?

Ideological Disidentification

Žižek also puts forward the idea of ‘ideological cynicism.’ Ideology today is not as it was for the proletariat for ‘they do not know it, but they are doing it.’ He disagrees that for ideology to be effective it has to effectively brainwash people, as Marx contended in his famous religion being the opium of the people assessment; rather Žižek contends that a successful ideology always permits a critical distance towards that ideology – this he terms ‘ideological disidentification’; saying: ‘I know well that (for example) Bob Hawke / Bill Clinton / the Party / the market do not always act justly, but I still act as though I did not know that this is the case.’

Or perhaps it should be said that behaviour has been modified or controlled, and widespread passivity makes it is irrelevant what we do in a spectator democracy. In effect, we are irrelevant to changing any of this, as the supporters of Bernie Sanders are finding out.

Žižek points to a ‘big O other’, who legitimates control through ‘God’ or ‘the Party’. In The Sublime Object of Ideology, (1989) he argues that such important or rallying political terms are ‘master signifiers,’ even though they are ‘signifiers without a signified’, i.e. words which do not refer to any clear and distinct concept or demonstrable object. Thus, they induce control and a false sense of belonging, but are meaningless.

This claim of Žižek’s is related to two other ideas:

- That subjects are always divided between their conscious and unconscious beliefs towards political authority;

- That subjects do not know what their beliefs are that leaves them open to domination and control.

Jouissance

Žižek further contends, following the critical theorist Louis Althusser, that ideology is embedded in our everyday lives. In particular, he uses the term jouissance to describe transgressive pleasure that we derive from the master signifiers, such as ‘nation’ or ‘people,’ through cultural products as sports, music, alcohol, drugs, festivals, or films.

Another central idea in Žižek’s initial political philosophy is that any regime only secure a sense of collective identity if their governing ideologies afford subjects an understanding of how these relate to what exceeds, supplements or challenges its identity. Or, in layman’s terms, bread and circuses is the glue that binds identities – ‘Football’s Coming Home’ to quote Baddiel and Skinner.

Žižek adopts the term ‘ideological fantasy’ for the deepest framework of belief that structures how political subjects, and/or a political community, come to terms with what exceeds its norms and boundaries. He identifies Law with the Freudian ego ideal.

But Žižek argues that, in order to be effective, a regime’s explicit Laws must also harbour and conceal a darker underside – a set of more or less unspoken rules which, far from simply repressing jouissance, implicate subjects in a guilty enjoyment in repression itself, which Žižek likens to the ‘pleasure in pain’ associated with the experience of Kant’s sublime.

Žižek’s final position about the sublime objects of political regimes’ ideologies is that these belief-inspiring objects represent the many ways in which the subject misrecognises its own active capacity to challenge existing laws, and to found new laws altogether.

He repeatedly argues that the most uncanny or abysmal aspect of the world today is the subject’s own active subjectivity – explaining his repeated citation of the Eastern saying ‘Thou Art That’. It is, finally, the singularity of the subject’s own active agency that leads to subjects’ recourse to fantasies concerning the sublime objects of their regime’s ideologies.

Like a Thief in Broad Daylight

Žižek’s technical term for the process whereby we recognise how the sublime objects of political regimes’ ideologies are, like Marx’s commodities, fetishised objects – concealing from subjects their own political agency – is ‘traversing of the fantasy.’

Traversing the fantasy, for Žižek, is the political subject’s deepest form of self-recognition, and the basis for his own radical political position, or defence of the possibility of such positions.

Žižek also references Alain Badiou, who argues for an elevation or an insurrection. Žižek also seeks a form of Jacobin army, the intellectual irresponsibility of which needs to be emphasised. Even if these ideas are metaphorical the extremism provides ample ammunition to right-wing critics, who argue he condones or even approves of terrorist methods.

Sadly, in more recent times, the Marxist left has been self-sabotaging, and the cause of its own downfall. They have also had their good arguments stolen and mangled by the right.

Yet it seems that radical Marxists are at last growing up and that the post-modernist wing is grappling with its self-contradicting, and implicit approval, of a valueless universe.

In his recent book Like a Thief in Broad Daylight (2016) Žižek distils many of the abstruse elements of his ideas into manageable and helpful commentaries that have a broader base of appeal. The ethical political order, notwithstanding Habermasean attempts at a reconstituted normalization, have collapsed, he argues.

Freedom of choice is an illusion in a world of disinformation, plummeting educational standards, short-terms contracts, imposed services and privatization. Any alleged freedom we have arrives in a narrow spectrum of choices, subtly imposed upon us through social influencers and technological nudges controlling choices. Or as John Gray put it in The Soul of The Marionette (2015) ‘we are forced to live as if we are free.’

Žižek and others have demonstrated the sinister developments within late capitalism. Including how a rent for profit model means most of us on low salaries serve undeserving sponsors, leading many into the informal market or the black market by violence or the violence of regulation – as David Graeber explores in his epochal work Debt: the First 5000 Years (2015).

Other disturbing trends are in evidence, Roberto Saviona in Zero, Zero, Zero (2015) through a sustained analysis of drug cartels, shows how the corporate model of Mafiosi loyalty has been exported into law firms. The lines between legitimate and illegitimate capitalism are thus blurred to a point of near non-existence.

The ‘woke’ left cannot escape blame for failing to identify the socio-economic issues that really count in peoples lives. Pseudo-feminism plays a class game, marginalizing lower class men as harassers and even demonizing migrants. Indulgence of victimhood has created the abuse excuse.

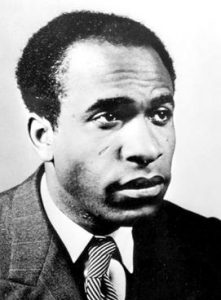

The Wretched of the Earth

Frantz Fanon

Žižek is quite critical of the great post-colonial Marxist Frantz Fanon and his seminal text The Wretched of the Earth (1961). But Fanon was surely right in identifying a colonial order wherein, ‘the people’s property and the people’s sovereignty are to be stripped from them.’ The Untermensch were obliged to pay the debts of the occupying powers, which is now the international model of austerity.

Žižek argues that our society of depoliticized and compliant sheep invite disaster. He references the film Blade Runner (1980), which is a useful cultural trope as the older replicants – baby boomers – now need to let go of their accumulated wealth and power. Generation X are at least conscious of false memory syndrome or implanted hopes, and some have the wherewithal to do something about it and no longer settle for being victims. So despite the victim excuse, Fanon and Žižek have much in common in their analysis.

The reality is that the analysis of Fanon is now in place across the world. The elite or the corporatocracy are a gang, and what amounts to a mafia is running the planet like a colony.

So the slovenly Slovenian has hit the zeitgeist, and now interacts with more common sense than was evident in his wilder pronouncements of the past. But unfortunately it appears as if the lunatics have already taken over the asylum, and to an increasingly docile audience what he is saying will appear mad, a point that his appearance would appear to affirm.

Or at the very least his ideas will be packaged by Facebook, so he plays a bit part in the drift or acceleration into the abyss that we must resist.