Dublin was the second city of the British Empire until end of the eighteenth century. After the Act of Union of 1801, however, many prosperous land owners departed the city and, indeed, by the end of the nineteenth century Belfast’s population was greater.

The former did, however, retain a residual aristocracy who formed the clientele for the few restaurants that emerged towards the century’s end; albeit, the absence, of a significant bourgeois class over the course of the twentieth century meant there was little demand for restaurants for those on middling incomes.

It was perhaps unfortunate for Irish gastronomy to have been colonised by the English who Voltaire described as being a nation of forty-two religions but only two sauces. Besides, Ireland was a poor country by European standards in the nineteenth and much of the twentieth century. The Great Famine was among the most devastating of its kind in human history. Culinary celebration was muted.

Nonetheless, numerous French chefs had already emigrated to Ireland to work in aristocratic households and gentlemen’s clubs by the time the first recognisable restaurant emerged in Dublin in 1861. The Café du Paris on Lincoln Place was intriguingly linked to a Turkish baths on the same premises. They advertised both dinners ‘a la carte and table d’hote; choicest wines and liqueurs of all kinds, [and]Ices.’

Jammet’s

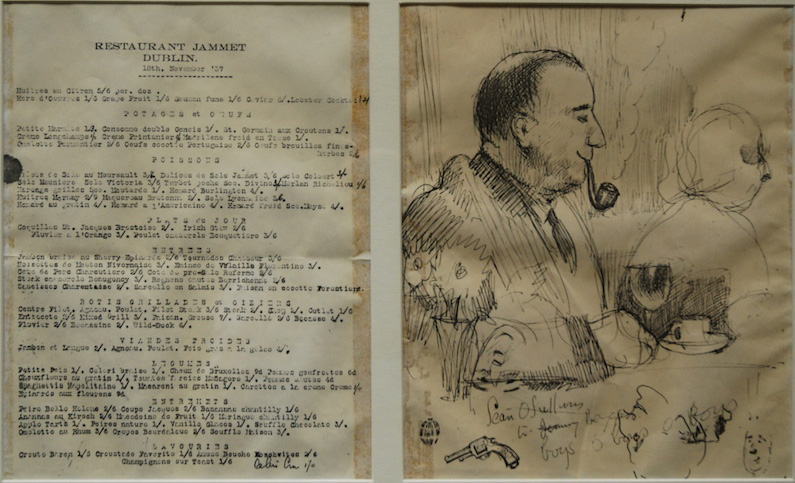

Any history of Dublin restaurants lingers on the legendary Jammet’s which was founded by two brothers from the Pyrenne,s Michel and Francois Jammet in 1901. They purchased the Burlington Restaurant and Oyster Saloon on Andrew’s Street in 1901 and renamed it Jammet’s. Michel had been chef to the lord lieutenant so knew all about what appealed to the aristocracy whose descendents continued to patronise the establishment until its demise in 1967.

In 1908 Francois Jammet returned to Paris leaving his brother in sole charge until 1927 when he handed the reigns to his Belvedere educated son Louis. By that time it had moved to Nassau Street to the site of the Porterhouse Central.

One observer from the 1940s describes the interior of the restaurant: ‘the main dining room was pure French second Empire, with a lovely faded patina to the furniture, snow white linens, well cut crystal, monogrammed porcelain, gourmet sized silver-plated cutlery and gleaming decanters.’ It was the hangout for artists and the literary set such as W.B. Yeats, Michael MacLiommar and Dudley Edwards as well as wealthy professionals and men of commerce.

The family first lived in Queen’s Park, Monkstown but moved to the sixteenth century Kill Abbey in the 1940s where vegetables were grown for the restaurant. A 1928 article in Vogue describes Jammet’s as ‘one of Europe’s best restaurants … crowded with gourmets and wits, where the sole and the grouse was divine.’

It was during the years of the Second World War that Jammet’s really came into its own as the location for the ‘finest French cooking between the fall of France and the liberation of Paris.’ Like other Irish restaurants, Jammet’s managed to evade restrictive rationing and serve customers the fare they were accustomed to. According to one observer ‘American servicemen, cigar-chomping and in full uniform, were streaming across the neutral border to sample the fabulous food in the prodigious quantities available here.’

Red Bank

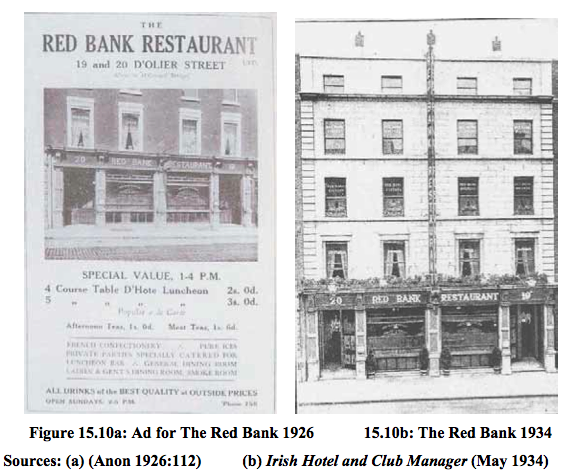

If Jammet’s was the location for Allied excess another long-established restaurant the Red Bank was the place of Axis intrigue. On April 22 1939 the German colony in Ireland celebrated the birthday of Adolf Hitler there. The Irish Times records: ‘A large portrait of Herr Hitler occupied special position in the special decorations. On either side of it were swastikas and every guest wore a swastika or Nazi party badges.’

Disturbingly in May 1940 as the Nazis Blitzkrieged through Europe, the ‘Irish Friends of Germany’ (aka the National Club) held a meeting in the restaurant that was attended by fifty people. George Griffin, veteran anti-Semite and ex Blueshirt, spoke on the subject of the ‘The Jewish Stranglehold on Ireland’. Griffin mentioned many Jews by name and went onto advocate that … we should never pass a Jew on the street without openly insulting him’.

The Blueshirts salute their leader Eoin O’Duffy.

The Unicorn

But Jewish émigrés were themselves involved in the restaurant trade and could dish out their own retribution. It is said that revenge is a dish best served cold but for Austrian Jews Erwin and Lisl Strunz from Vienna it could be salty too.

They escaped from Vienna in 1938 and purchased a premises on Merrion Row which they called the Unicorn. They bought it for a song as Irish people thought the premises was haunted after W.B. Yeats had supposedly conducted séances there.

Lisl would cook her mainly Austrian dishes while Erwin entertained at the front of house. He reminisced ‘during Christmas 1940 when all the lights had gone out over Europe I played my guitar in the restaurant and sang Christmas carols and folk songs in eight languages.

But not all comers were welcome. When Edouard Hempel and his acolytes from the German legation visited Erwin became apoplectic with rage. But he kept his wits about him and calmly took their orders. Before each plates was delivered he doused each one with enough salt to clear a frosty driveway. Hempel nearly choked and the whole table walked out and never returned.

After the war the Unicorn was sold to an Italian family the Sidoli’s and it brought exotic ingredients like pasta to its Dublin clientele. It also involved females chefs which was unusual for the male dominated profession in Dublin.

Another immigrant who came to Ireland to work in the restaurant trade was Zenon Geldof a Belgian citizen who set up a restaurant called Café Belge. His grandson Bob retained an ambition to feed the world.

Steeped in the haute cuisine tradition of Escoffier Jammet’s continued to prosper after the war when it was joined by other restaurants including The Russell.

Ireland’s first phD in the history of food, Máirtín Mac Con Iomaire argues that on a per capita basis in the 1950s Ireland was the gastronomic capital of the British Isles. Although this may not have been that great an achievement as given the nadir that English food had reached by the 1950s. Elizabeth David wrote of her experience in one English restaurant of the time: ‘there was no excuse, none, for such unspeakably unpleasant meals as in that dining room were put in front of me. To my agonized homesickness for the sun and southern food was added an embattled rage that we should be asked – and should accept – the endurance of such cooking.’ Perhaps she should have visited Dublin.