Midway upon the journey of our life

I found myself within a forest dark,

For the straightforward pathway had been lost.

Dante Alighieri

Religion is an emotional need of mankind. The rationalist may not want it, but he has to admit that other people may…

Let’s not leave out a single god! […] Let’s be everything, in every way possible, for there can be no truth where something is lacking.

Fernando Pessoa

The Taliban reconquest of Afghanistan came as a shock to Western consciousness. It was not merely that a U.S.-sponsored regime proved so fragile once the troops pulled out; but the apparent enduring appetite among Afghans for policies at least purporting to be Islamic flies in the face of a starry-eyed view of humanity steadily evolving towards a uniform set of customs and beliefs.

That is not to argue that common principles cannot be agreed by sovereign states – and peoples – but to expect uniformity in outlook across a global population living in starkly differing circumstances, and at varying historical junctures, appears naïve at best. Any globalisation project striving for homogeneity will surely fail.

In abandoning religious traditions – as many of us have done – it may be that we are losing ethical frameworks grounded in those traditions with profound consequences for relations among ourselves, and with Earth itself. It begs the question: at a critical juncture for humanity does faith, or transcendence, offer a path out of despair, and indeed a Theology of Hope? We may further ask whether, without this ethical grounding, if the direction of scientific research is guided by a reliable moral compass, or simply the exigencies of a Capitalist market?

Frank Armstrong explores the historical origins of capitalism, as the steady financialisation of property threatens the good life we have a right to expect.https://t.co/Lq7z4PeWCP@broadsheet_ie @BowesChay @liamherrick @williamhboney1 @KevinHIpoet1967 @VillageMagIRE @RoryHearne

— CassandraVoices (@VoicesCassandra) September 15, 2021

Peace on Earth

Without subscribing to the banal equanimity of moral relativism disregarding gross human rights violations, we should question all military interventions in pursuit of peace. Saint Augustine in the City of God stated: ‘there is no man who does not wish for peace… even when men wish a present state of peace to be disturbed … they do so not because they hate peace but because they desire the present peace to be exchanged for one that suits their wishes.’ The Hippocratic Oath might be adapted in international relations whenever the invasion of another country is contemplated: ‘first do no harm.’

The idea of peace for eternity is an illusion. So Francis Fukuyama’s The End of History and the Last Man (1992) – where ‘the struggle for recognition, the willingness to risk one’s life for a purely abstract goal, the worldwide ideological struggle that called forth daring, courage, imagination, and idealism’ is ‘replaced by economic calculation, the endless solving of technical problems, environmental concerns, and the satisfaction of sophisticated consumer demands’ – now seems an increasingly absurd notion, formulated in a moment of peak post-Cold War hubris.

Likewise, a Marxist assumption that History will simply end, thereby removing a requirement for politics, or for difficult choices to be decided is also, sadly, Utopian; this is notwithstanding the continued relevance of Marxist analysis to current economic relations, in particular a seemingly inexorable widening in the gap between rich and poor in an age of technology; and the idea of metabolic rift, meaning, broadly: the alienation of exploited workers from their environment.

Thus, both Liberals and Marxists have fallen prey to an assumption that we are bound for a Promised Land governed by Enlightenment Values. In fact, Enlightenment philosophers such as David Hume called into question fundamental rights derived from an Aristotelian tradition, developed in Europe over centuries. Science only emerged as a distinct discipline in the 1830s, untethered from an ethical foundation in philosophy.

U.S. President Reagan meeting with Afghan mujahideen at the White House in 1983.

Religion in Global Diplomacy

The Taliban’s victory demonstrated that religious identity remains a galvanising force in politics, beyond even national identity, in the developing world especially. Although, it should be noted that the Taliban is largely drawn from the dominant Pashtun ethnic group. We may also safely assume a long Afghan tradition of resistance to foreign occupation remains an inspiration.

Nonetheless, as the case of ISIS also highlighted, and indeed the perseverance of the Religious Right in the U.S., we in Europe especially should reconcile ourselves to the endurance of belief systems other than our own dominant secularism. For, as the authors Philip McDonagh, Kishon Manocha, John Neary and Lucia Vázquez Medonza of a new work On the Significance of Religion for Global Diplomacy (Routledge, London, 2020) point out, it is a fallacy to equate ‘modernisation’ with a decline of religious observance.

This work provides an important guide to negotiate challenges in a world where those professing no religion amount to just 16% of the population. Globally, atheism is a strictly a minority taste, a point its often evangelical advocates are wont to ignore. Thus, in the half century since Iran’s Islamic Revolution in 1979, we have witnessed a succession of political movements emerge shaped by religious identities – if not the humane insights contained within all traditions.

Show on the life of Jesus at Igreja da Cidade, affiliated to the Brazilian Baptist Convention, in São José dos Campos, Brazil, 2017

Religion as a Force for Good and Ill

Anyone advocating in favour of a place for religion in the public sphere must grapple with a strong tendency for this to be expressed in fundamentalist politics – a word, incidentally, deriving from the description of Protestant sects of the early twentieth century. All too often, where religion lies behind political formations it has brought harsh ordinances, generally to the detriment of women – in terms of their status relative to men – in a patriarchal order.

In power as such, we have witnessed the crushing of dissent, or heresies. Indeed, the approach of many rulers claiming faith-based authority resembles that of the Grand Inquisitor from Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s The Brothers Karamoz, who Laurens van der Post described as ‘the visionary anticipation of Stalin and his kind.’ This tale or parable, which the character of Ivan Karamazov’s recounts in the novel, is set in post-Reformation Spain, where the all-powerful Inquisitor is visited by a resurrected Christ. The fearsome leader, however, dismisses the putative saviour, revealing that the Church has embraced the devil:

we have accepted from him what You had rejected with indignation, that last gift that he offered You, showing You all the kingdoms of the earth: we accepted Rome and the sword of Caesar from him, and we proclaimed ourselves the only kings on earth, the only true kings.

The Grand Inquisitor maintains that he is serving the common people, who will be lost if freedom of conscience is permitted. He thus banishes the saviour with the words: ‘we shall withhold the secret and, to keep them happy, we shall opiate them with promises of eternal reward in heaven.’[i]

Characteristics of the Grand Inquisitor’s approach were evident in the Irish Catholic Church after independence that opiated the people “with promises of eternal reward in heaven.” Thus, Ronan Sheehan describes a ‘Theology of Incarceration’ – associated in particular with the legacy of Matt Talbot in his visionary Dublin: Heart of the City (2016).

The example of Matt Talbot's piety was used by the Irish Catholic Church in inculcate subservience as the downtrodden were told to await their reward in heaven.https://t.co/8uOS8DgHKe@broadsheet_ie @vincentbrowne @fotoole @connolly16frank @gemmadunleavy1 @AlanGilsenan1

— CassandraVoices (@VoicesCassandra) January 20, 2021

However, notwithstanding criminal actions of Catholic clergy, we may question whether contemporary Ireland is a more, or less, caring society. There are certainly greater opportunities for women – but in an increasingly two-tier society in housing, health and education it is a shrinking number that can avail of these.

In an increasingly neoliberal society political ambitions have given way to passivity. The authors of On the Significance of Religion for Global Diplomacy remind us that twentieth century history witnessed resistance to National Socialism, and plans for the Welfare State ‘inspired to a large extent by leaders who were religious leaders.’ There are numerous examples of religious leaders and movements in developing countries, from Gandhi to Hamas, that have emphasised the importance of social programmes. The Catholic Church under Pope Francis is also now engaging seriously with many of the profound social and environmental questions of our age.

Percy Bysshe Shelley 1792-1822.

Poetic Origins

A more acceptably entry to the idea of religion – for a younger generation anyway – is perhaps through poetry. The authors of On the Significance of Religion for Global Diplomacy locate religion in poetic inspiration, which has often arrived in response to tyranny, as in Percy Bysshe Shelley’s plea in ‘The Masque of Anarchy’ (1819):

Let a vast assembly be,

And with great solemnity

Declare with measured words that ye

Are, as God has made ye, free–

Shelley wrote the first public argument for atheism in England as a young student in Oxford, but this may be considered an undergraduate flourish, designed to provoke. As his career developed, according to his wife Mary Shelley, he became a ‘disciple of the Immaterial Philosophy of Berkeley. This theory gave unity and grandeur to his ideas, while it opened a field for his imagination.’[ii]

Shelley’s work emphasised a divine inspiration, and believed a poet’s ‘impartial care for the birth of situations’ reaches towards goodness. Likewise, Osip Mandelstam said ‘the consciousness of our rightness is dearer to anything else in poetry.’

Many poets maintain, at least in private, that their inspiration, including that conveying moral ideas, is in a sense, god-given, or at least derived from an ‘other’ world. Thus, the Ancient Greek poet Hesiod describes a certain kind of judge, touched by the Muses, who ‘can put a quick and expert end even to a great quarrel.’ Viewed as such, religion may yet offer a poetic space for developing empathy, imagining a new world, and holding on to what remains sacred in a dying planet.

For the authors of On the Significance of Religion for Global Diplomacy, the formulation of ‘a more just arrangement of human affairs’ comes about not only through philosophical reasoning, but also in a Theology of Hope. Thus, the say ‘the meaning or pattern in events shines out in the perspective of eternity.’ This is the faith of a Dietrich Bonhoeffer who believed that ‘something new can be born that is not discernible in the alternatives of the present.

Therefore, the authors ‘do not argue for theocracy in any form,’ and instead ‘argue merely that to try to exclude God and religion from the conversation would be about our global future is to aim deliberately low.’

Everything is Permitted?

Does the negation of religion – however tenuous and abstract – leave us operating within a moral void, where, as in the words of Ivan Karamazov: ‘everything is permitted,’ including murder? This is not to say that all atheists operate without moral scruples, but ultimate justifications for “rightness” or “goodness” may prove elusive in the absence of faith or transcendence. Through the character of Ivan in The Brothers Karamazov, Dostoyevsky wonders what deeds we are capable of in the absence of divine judgment.

More broadly, we may ask whether a new species of evil develops in a value-less neoliberal setting, where callous murders are increasingly commonplace – not least in the gangland shootings we have grown accustomed to in Dublin in recent times? Is it simply fear of being caught in the act that holds back more of us from committing heinous crimes?

Contemporary alienation has been powerfully expressed by Michel Houellebecq the French author of Atomised (1998) and other novels. His latest offering, Serotonin (2019) again plumbs the depths. Here, we find a narrator contemplating the murder of the four-year-old son by another father of the love of his life, after coming to the conclusion the child would stand in the way of a successful revival of their relationship.

His mind returns to his own feelings as a young child after a New Year celebration. Adopting a neo-Darwinian, (scientific?) outlook, he observes:

it was as that memory came into my mind that I understood Camille’s son, that I was able to put myself in his place, and that identification gave me the right to kill him. To tell the truth, if I had been a stag or a Brazilian macaque, the question wouldn’t even have arisen: the first action of a male mammal when he conquers a female is to destroy all her previous offspring to ensure the pre-eminence of her genotype. This attitude has been maintained for a long time in the human population.

He continues:

I don’t think that contrary forces, the forces that tried to keep me on track for murder, had much to do with morality; it was an anthropological matter, a matter of belonging to a late species, and of adhering to the code of that late species – a matter of conformity.

Overcoming “conformity”, ‘the rewards would not be immediate’ he says, ‘Camille would suffer, she would suffer enormously, I would have to wait at least six months before resuming contact. And then I would come back, and she would love me again.’[iii]

Houellebecq’s “contrary forces” represent an increasing loss of moral conviction. As the characters conformity diminishes, the “code” of our “late species” breaks down and the possibility of violence increases, as we see in the book’s characterisation of the violent response of farmers to a neoliberal order that is putting them out of business.

Ultimately, however, Houellebecq’s narrator proves incapable of pulling the trigger as he has intended, entering what he refers to as an endless night, ‘and yet’, he says:

deep within me, there remained something less than a hope, let’s say an uncertainty. One might also say that even when one has personally lost the game, when one has played one’s last card, for some people – not all, not all – the idea remains that something in heaven will pick up the hand, will arbitrarily decide to deal again, to throw the dice again, even when one has never at any moment in one’s life sensed the intervention or even the presence of any kind of deity, even when one is aware of not especially deserving the intervention of a favourable deity, and even when one realises, bearing in mind the accumulation of mistakes and errors that constitute one’s life, that one deserves it less than anyone.[iv]

Hope springs eternal it seems, even in a novelist-of-despair such as Houellebecq.

Moreover, if we refuse the temptation to pull the trigger and reset our lives; if we embrace an idea of hope; we may conceive the Earth itself to be sacred; a view shared by all religious traditions, which enjoin respect towards all life on the planet. One wonders whether a view of all life on Earth being sacred is shared by pure materialists. Moreover, untethered to any faith tradition is “everything permitted” in scientific research?

Niccolò Machiavelli 1469-1527.

The Political Craft

Contemporary politics often appears to operate within a moral vacuum, where warfare is conducted through drone strikes, and the planet reels under the impact of over-exploitation; while even in Advanced Economies, millions endure shocking poverty. New forms of propaganda have been unleashed via a social media that is removing agency, implanting ideas that distort politics. Most politicians claim to care, but as often as not they distract from the structural questions and emphasise issues of only peripheral relevance to the lives of ordinary people. In particular, identity politics has been used to divide and conquer, while the wealth of billionaires continues to accumulate.

The authors of On the Significance of Religion for Global Diplomacy come down squarely against the statecraft associate with Niccolò Machiavelli, which now appears ascendant in a contemporary politics of spin – where September 11 was ‘a good day to bury bad news’. Here, according to the authors: ‘Deceit, and even cruelty, are justified by results – by their results as measured over time – which requires very sharp judgment by the Prince if his recourse to realpolitik is not to undermine the moral standards of ‘ordinary people.’’ Means cannot easily be distinguished from ends, while the body politic is contaminated by mendacious politicians.

They argue: ‘Not to tell lies or to make contradictory promises would seem to be a rule of peace-building that we should never set aside.’ Lies erode trust in institutions and tend to catch up with political actors. Tony Blair and his 45-minute claims before the invasion of Iraq in 2003 is an obvious example, albeit one unmentioned in the book.

Image (c) Daniele Idini

Pandemic Response

A Populist wave emanating from the Americas has, thus far at least, failed to propel a European equivalent into power. Nonetheless, distrust in politicians and the media is probably at an all-time high, and with some justification. Moreover, all too often, scientists guiding government policy have adopted Machiavellian approaches that only fuel paranoia.

The origins of the pandemic itself are shrouded in mystery, amidst a growing suspicion that the COVID-19 virus is a product of so-called ‘gain of function’ research, involving US government agencies and China.

Attempts to supress this involvement – including by EcoHealth’s Peter Daszak, who jointly authored an article in The Lancet dismissing the idea out of hand at the beginning of the pandemic – generates serious concern. A recent slew of emails released under freedom of information: ‘indicate involvement by individuals with undisclosed conflicts of interest; limited peer-review; and a lack of even-handedness and transparency regarding the consideration of lab-origin theories within the scientific community.’

Would anyone who believes in the sacredness of life on Earth engage in work so fundamental to all life on Earth? It recalls the inventor of the Atomic Bomb Charles Oppenheimer’s quoting The Bhagavad Ghita: ‘I am death destroyer of worlds.’

Ethical debates in science would surely benefit from religious insights. As Laurens van der Post put it: ‘For me the passion of spirit we call ‘religion’, and the love of truth that impels the scientist, come from one indivisible source, and their separation in the time of my life was a singularly artificial and catastrophic amputation.’

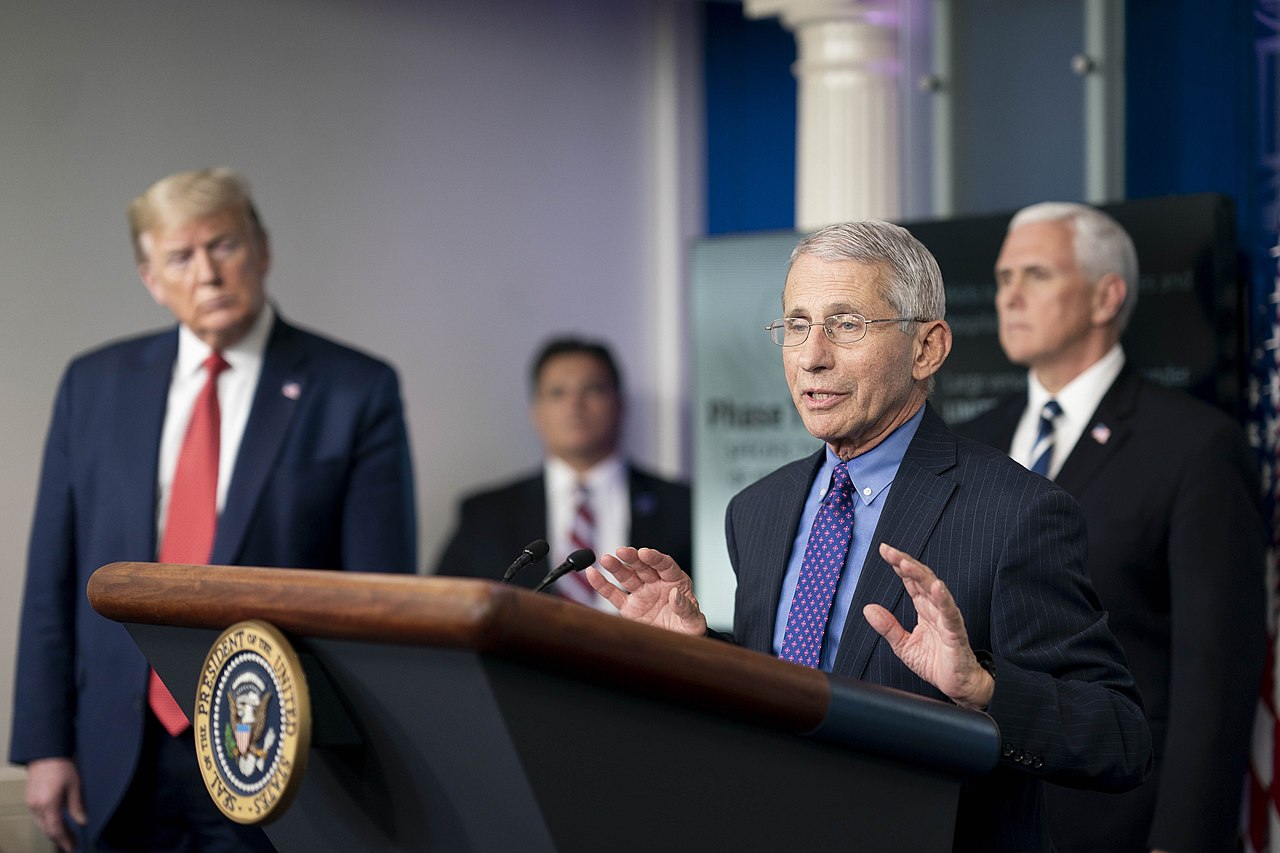

Fauci speaks to the White House press corps on COVID-19 in April 2020.

Bioterror Czar

Damningly, in 2011, in the capacity of George Bush’s ‘bioterror czar’ the long-time Director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) and the Chief Medical Advisor to the President Anthony Fauci argued that the benefits of ‘engineered viruses’ made it a ‘risk worth taking.’

During the pandemic Fauci appeared as a rational antidote to the bleach-belching Trump, but is prone to an arrogance assuming he can do no wrong. This is epitomised by the remarkable statement: ‘A lot of what you’re seeing as attacks on me, quite frankly, are attacks on science.’ In other words, Le Science C’est Moi.

An early example of Fauci’s mendacity was his claim that he committed a ‘white lie’ in relation to the efficacy of masks. He said that he shaded the truth to avert a run on scarce equipment. Even if we take him at his word, why should the public believe what he is saying thereafter is not also a white lie? This is the attitude of a Grand Inquisitor who believes the little people cannot hope to understand the big questions. But this Machiavellian approach easily backfires.

As David Bromwich in The Nation put it:

In this testimony, as in much of his conduct over the past two years, Dr. Fauci was speaking “nothing but the truth.” Yet he was mindful of what Jesuits used to call a reservation.

A reservation, in this sense, is an unspoken qualification. The speaker telegraphs a public meaning, confident it will be misunderstood. He holds in reserve a private meaning whose release might damage a higher cause (a cause known to the speaker and God, of which God approves). For God, in this context, we should read: “US government institutions of scientific research.” Yet American support of catastrophically hazardous experimentation was by no means the only pertinent fact withheld from American citizens.

There are perhaps programmes that a government can justifiably occlude, but it enters dangerous territory in doing so. Fauci’s over-weening arrogance – tying his own fate to the credibility of science which is enshrined as the guiding light for humanity – appears to have led him to the moral failings of the Grand Inquisitors that we associate with religions in power.

Black Lives Matter Dublin Protest June 1st 2020.

A Point of Inflection

The authors of On the Significance of Religion for Global Diplomacy stress a need for preserving universal values, and institutions, while upholding a spirit of hopefulness in the face of seemingly insurmountable challenges for humanity. History shows that democratic institutions alone cannot be trusted, given the extent to which opinions are moulded using increasingly sophisticated propaganda. This is one reason why we have constitutions that purport to contain immutable and even transcendent values.

As the authors stress, ‘we have reached a point of inflection in the global story’ and if they are to address forthcoming challenges religions ‘need to make themselves understood in the common language of reason.’

The input of the billions of religious should be welcomed in our public discourse, and not associated with ignorance in a one-track view of development. In particular, the idea of all life on planet Earth being sacred should be affirmed, although tendencies towards authoritarianism and mendacity among representatives of religions requires attention.

In an age of science, where humans act as gods, altering the building blocks of life we can draw on wisdom contained within religious traditions on the sacredness of life. In a world of mounting challenges, even those of us who have dismissed religion from our lives may benefit from consideration of core principles contained therein. In any case, we must navigate a path through a world where, like it or not, religious belief remains the norm.

Featured Image: The Thinker in the Gates at the Musée Rodin

[i] Fyodor Dostoevsky, The Brothers Karamazov, translated by Ignat Avsey, Oxford World Classics (1994), p. 322-325

[ii] Kenneth Neill Cameron ‘Philosophy, Religion and Ethics’ in Shelley: The Golden Years, Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press, 1971, p.151

[iii] Michel Houellebecq, Serotonin, translated by Shaun Whiteside, Penguin, London, 2019, p.265-266

[iv] Ibid, p.270