I loved working for the NHS (National Health Service), especially as it was configured in Bradford, West Yorkshire. Bradford was a health action zone, and probably still is due to its high level of social deprivation. This meant it got more funding for health and social initiatives.

Darndale, Dublin or Moyross, Limerick would be areas with similar issues. The practices in Bradford were large and covered virtually everything except performing major surgeries and delivering babies, meaning there was an eclectic mix of health professionals, all under the same roof. This was referred to as a ‘primary care team’. A team?

After completing my undergraduate training in Dublin I arrived under the impression that being a GP was essentially a solo effort, a bit like being a snooker player.

In his own eyes the GP is the hero, even if in Ireland he is a failed consultant in other people’s view. Not so in the NHS, and certainly not in Bradford, where GPs were part of a multidisciplinary team approach to the provision of health services. Each person was a cog in wheel that contained management, administration, nursing, occupational therapy, physiotherapy and community pharmacy services. They even held meetings, spoke to each other civilly and advice flowed in various directions. How radical!

On a wider scale, local practices provided many of the out-patient services traditionally provided by hospitals including cardiology, neurology, rheumatology and chronic disease management; they even carried out minor surgery and endoscopies. GPs were encouraged to upskill to become what they called ‘GPs with special interests’ or GPSI (pronounced Gypsy). All of this occurred in close proximity to their patients and in familiar surroundings. These practices were based in large urban centres, although I would imagine it would have been difficult to replicate this model in rural areas with widely dispersed populations.

Unemployed outside a workhouse in London in 1930.

Beveridge Report

The NHS emerged in a society with a different history to Ireland’s. The 1942 Beveridge report highlighted that urban poverty was widespread in the U.K., as George Orwell’s account in The Road to Wigan Pier bears testament. One can get all misty-eyed about Beveridge’s recognition of the plight of the working class; the reality was a fear that workers’ poor health would impact on profits, and might turn revolutionary.

Nevertheless, the post-War drive to correct some of these deficits lay behind the birth of the Welfare State, including the establishment of the NHS in 1948. This was strenuously resisted by the medical profession, much as the profession in Ireland, along with the Catholic Church, were resistant to Noel Browne’s Mother and Child Scheme. More latterly the mere mention of ‘Sláintecare’ induces apoplectic rage among certain members of the ‘caring’ profession.

This may seem naïve, but I fail to see what’s wrong with a universal health service, ’free at the point of entry from the cradle to the grave’, paid for out of taxation revenue and borrowings; this is a service that encourages the utilisation of all health-related services in a country, public and private, for all citizens, based not on ability to pay, but need. But apparently this isn’t a good idea.

I have come across many ideas that were thought not to be good ideas in my twenty-seven years of practice, but few had credible reasons for their outright rejections. Chronic disease management, i.e. diabetes, heart failure, COPD or renal failure should be undertaken by a person known to the patient – i.e. a GP – living in close proximity to where they live.

‘Too Busy’

This has been the bread and butter work of GPs in the U.K. since the 1990s, but apparently in Ireland during the 2000s this wasn’t a good idea, because we were ‘too busy’. Doing what I wonder?

Integrated services would allow GPs to order investigations directly. In Ireland at present, if, for example, a chap without health insurance injures his knee playing Sunday football and his GP thinks it could be a torn cartilage, he will have to wait up to two years to see an orthopaedic surgeon. He is then put on a waiting list for perhaps another year, until finally he has his MRI scan and discovers he has a torn cartilage.

By that time, however, he is no longer playing football and is twenty kilos overweight, having spiralled into an unhealthy lifestyle. To add insult to injury he will receive a letter from the hospital asking if he wishes to remain on the waiting list for his knee operation, by which stage he might as well get in the queue for a knee replacement.

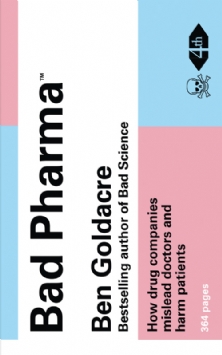

Big Pharma

Nowadays, it’s not a good idea to refuse to meet pharmaceutical reps when they call to the practice. Having trained in Bradford – where none of the practices or the training scheme’s educational events gave access to reps – I thought that it was reasonable to turn them away. We didn’t meet reps selling toilet rolls or coffee, so why meet representatives of multibillion dollar pharmaceutical corporations? Such companies spend more on advertising and marketing than research because they know how it works.

Alas, we dopey doctors assume they are sharing their scientific data with us whilst buying us lunch, giving us pens (with names of drugs emblazoned on them), stationary, wall clocks, mugs etc. So, they do share ’their’ science, the bits of their research that shows their product in a good light, not the science or the research warts, or heart attacks, and all.

After all, we G.P.s are trained professionals and would never be influenced by such inducements. Forget about the science demonstrating a correlation between drug prescribing and frequency of pharmaceutical rep visits.

Cosy World

A cosy world of Irish general practice featuring golf, rugby and tweed had been frozen in time until 2008. The GMS contract which began in 1970s paid well, but we still had our ‘privates’. In other parts of the English-speaking world ‘privates’ usually refers to one’s genitalia, but in an Irish GP setting this refers to the paying customer.

In some practices private patients are given preferential access to appointments. Invariably, this will involve nothing more than prescribing an antibiotic for a cold. Such patients usually have their own cardiologist or several oncologists they refer to using their first names. However, from 2008 onwards when the International Monetary Fund invaded Ireland and took control of the purse strings, the government of the day unilaterally took 35% off the GMS contract payments. Then the privates became more important, but these patients were increasingly hard up too with the world’s economy in a mess.

The next few years for me remain a blur. My recollections arrives through the haze of mental illness and stress brought on by a Celtic Tiger mortgage, business partnership shenanigans, and yo-yoing emigration-immigration, amongst other adventures.

Image (c) Daniele Idini

Pandemic

Fast forward to 2020 and the unknown quantity that was the Sars-CoV2 escape from Wuhan’s virology research centre – known as the Wuhan Wet Market dose to some, depending on your trust in media, governments and power elites.

Then the WHO advised GPs via august bodies such as the Irish College of General Practitioners to do nothing, as there were no treatments despite it being a deadly pandemic. Furthermore, we didn’t even need to see patients. We locked our doors, sat by the phone, ‘stayed safe by staying apart,’ among a litany of other trite statements.

It was heartening to note on some well-known GP websites that some practitioners were one step ahead of WHO/HIQA/NPHET insofar as they immediately sensed a threat to ‘the privates’. Not as an unwanted symptom of a Sars-CoV2 infection, but as a result of the hatches being battened down. How could the privates access their GPs and more importantly pay them?

The unelected and widely disrespected government with its GP-trained Taoiseach knew instinctively what to do. More accurately Leo Varadkar knew what to do. He found the answer to this most perplexing question and saved the day. Make everyone private. GMS patients ringing up resulted in a fee, privates ringing up resulted in a fee from the government.

So the gravy train sloshed its merry way through the pandemic. An entire profession was bought, and continues to be bought by vast sums of money for examining patients that one is already being paid for, vaccinating all and sundry against influenza, Sars-CoV2-twice or is it three times, who knows, who cares, the money spigot is stuck on maximum flow.

Money that was not available up to 2020 is now flowing like goodies from the proverbial cornucopia. This has bought compliance with ways of treating people that run counter to the codes of practice of any good doctor.

Practices are now treating patients like lepers, creating nonsensical plastic barriers, one way passes through surgeries, discouraging unvaccinated patients, disrespecting patient autonomy, and offering a paternalism reminiscent of the Victorian era. But worst of all is a refusal to treat patients in the early stages of Sars-CoV2, regardless of how medically vulnerable they may be because of ignorance and hubris.

This is what buying a profession produces.

Image: Daniele Idini.

Eau de BS

Born and reared in a working class Dublin area with a healthy disrespect for all authority, I have always been a contrarian. That disrespect has served me well. So, when I hear people in authority asking citizens to pull together or to do deeds for the good of the nation I instinctively smell eau de BS.

Supposedly for the good of the nation, we are creating a society that is comfortable with meaningless segregation based on vaccination status that is supported by the medical profession. We even have the prospect of hospitals taking young people off transplant lists and families being refused access to a dying loved one in a care home. Now we are witnessing a clamour for a dubiously effective pharmaceutical product to be inflicted on children as young as five.

The medical profession has allowed one of the highest levels of trust to be stolen by greedy fools who use it to ensure people think that their products can also be trusted. The medical profession has become avaricious, self-serving, vindictive, patient-averse, opinionated and authoritarian, and is failing to foster the doctor-patient relationship.

I fear that relationship which is the bedrock of general practice has been irrevocably damaged. What need then will there be for GPs if artificial intelligence can deliver the information in an up-to-date, rational, non-judgemental and timely fashion in the comfort of anyone’s home?

It seems that when this older generation pass into retirement, a tech savvy generation will not want what they never really had: a genuine doctor-patient relationship.

Featured Image: Aneurin Bevan talking to a patient at Park Hospital, Manchester, the day the NHS came into being in 1948.