The three mantra for this pandemic in Ireland are: wash your hands; socially distance; and wear a mask. Stated repetitively with suitable gravitas the guidelines have been internalised by most of the population. Fears around the spread of the ‘deadly’ virus are even driving people to police one another. The valley of the squinting windows is alive and well.

But what are the inherent costs to these three injunctions? And why shouldn’t we keep measures in place when this pandemic abates, as has recently been argued?

Throughout this pandemic we have witnessed very little meaningful scientific debate in Ireland. Irish experts are drawn from a small circle of academics, some with vested interests, supporting the government’s highly successful publicity campaign. In other countries, in contrast, there are heated public debates between scientists as to whether to adopt a dominant approach of blanket policies, or one of shielding elderly populations.

But in Ireland Nobel laureates and professors from prestigious universities around the world are routinely dismissed with smart quips by gullible journalists. But let us examine the three mantras in a dispassionate way that acknowledges each of their adverse impacts.

Wash Your Hands

The first injunction to ‘wash your hands’ is sound advice, which unless you are living on another planet you will be aware of by now. Do we always follow this injunction? Probably not. Are we all dying of ghastly flesh eating infections or coughing up great globules of blood stained mucus? No we are not. Why? Because very few of the billions of micro-organisms with which we share our bodies are actually pathogenic.

We have existed as a species for approximately a quarter of a million years, and as part of the great evolutionary flow of life for over four and half billion years. In that time adaptation to adversity has been the rule; hence homo sapiens is now thriving, sadly often to the detriment of the rest of the natural world.

In the advanced economies at least, most of us are now almost invincible until old age. Thus, over the past two hundred years improved nutrition, housing and sanitation have brought life expectancy up to almost eighty years in many countries.

Medical science, including antibiotics and vaccines, has contributed to this longevity, but not to the extent some of us doctors would have you believe. The authors of The Changing Body: Health, Nutrition and Human Development in the Western World since 1700 (Floud et al., Cambridge, 2011) state:

it would be easy to exaggerate the importance of scientific medicine when one considers that much of the decline in the mortality associated with infectious diseases predated the introduction of effective medical measures to deal with it

So yes washing your hands regularly is a good idea. Soap and water should be the principle means, not the bactericidal or viricidal gels we now find on entering every shop or building, some of which are to be avoided – especially the 52 sanitation products the Department of Education has told schools to refrain from using.

Our skin harbours myriad micro-organisms – that form a part of the human microbiome – all vying for space to live, raise a family and grow old peacefully in a quiet stable neighbourhood. They generally live harmoniously with us in what is referred to as a state of homeostatic balance.

What happens when we kill off all the good micro-organisms, repeatedly, just in case there is a bad micro-organism on our skin? First, these agents damage our skin’s protective oil barrier, and kill micro-organisms with which we live symbiotically, contributing to our health and wellbeing.

These ‘good’ bacteria and other microorganisms are easily replaced by ones that are resistant to the effects of the gels, and who can then run amok when given the chance.

Prior to this pandemic, excessive hygiene measures against infections has given rise to the hygiene hypothesis, according to which ‘the decreasing incidence of infections in western countries and more recently in developing countries is at the origin of the increasing incidence of both autoimmune and allergic diseases.’ So let us be on our guard against excessive hygiene.

“Social” Distancing

Hannah Arendt in 1933.

The second part of the mantra and perhaps the most dystopian is the injunction to distance ourselves socially. It recalls Hannah Arendt’s warning in The Origins of Totalitarianism (1951) that ‘The evidence of Hitler’s as well as Stalin’s dictatorship points clearly to the fact that isolation of atomized individuals provides not only the mass basis for totalitarian rule, but is carried through to the top of the whole structure.’

This “safe” distance is anywhere from the depth of the average grave – two metres – to imprisoning ourselves in our homes and limiting the number of fellow humans we allow to enter that space, which is no one from another household under current ‘Level 5’ Irish regulations; or previously an arbitrary number such as six, a figure no doubt chosen after repeatedly employing the reading of the runes technique.

Not seeing anyone at all would be ideal, but the illuminati could not depend on the imbecilic general public abiding by their lofty standards, or reverting to having sex online to limit the spread of the virus, and so some meagre concessions have been made to human frailty, with the advent of support bubbles.

Yet social isolation is a potential pathway to madness and a lonely death. We are social creatures and in solitary confinement few can flourish. A Screen New Deal is a recipe for Surveillance Capitalism, and enrichment of the billionaire class. Human touch brings emotional balance and better health.

A person may be technically alive but is he or she really living without conversing directly with others, dancing, or otherwise demonstrating his love and empathy? We are not avatars in a complex, visually stunning computer game. We are connected physical beings. Those connections extend back into the past, embrace the present, and reach forward into an unknown future.

It is impossible to tell whether the shocking spate of domestic homicides and suicides that occurred in the last week of October in Ireland, just as stricter measures were introduced, are the product of isolation, but the UN has described the worldwide increase in domestic abuse as a ‘shadow pandemic’ alongside Covid-19.

Irish incidents include a murder-suicide in Cork involving a father and two sons; the apparent murder of a mother and her two children in Dublin; and the death by suicide of a Dublin nurse along with the death of her young baby through asphyxiation.

Moving forward, we just have no idea what effect the injunction to “socially” distance – and the attendant loss of touch will have on us – a very tactile people.

Recall that in shaking hands we make character judgements based on grip and duration; we embrace and kiss those we love with warmth and energy, and those we like with fleeting touching cheeks; we cup the faces of babies and ruffle the hair of cute children – especially if they possess more than us.

We are now ordered to stop doing all of that, but for how long? Is there any evidence to suggest ‘the virus’ passes from one healthy person to another when we hug? Hasn’t common sense always dictated that we avoid hugging when we are under the weather?

In this precarious age, however, it is necessary to assume we are guilty of being ‘asymptomatic’ into what seems like an interminable future, and either hug with extreme caution, or not at all. I fear these tactile behaviours will disappear altogether given Covid-19 is very unlikely to vanish.

Mandatory Masks

The third and final of the government’s mantras is perhaps the most pernicious: the mandating of masks. It has infantilised the population and turned people into part-time police officers.

We’ve heard Irish and other experts overturn forty years of science, allowing celebrity doctors to demonstrate to the Irish public, with a cheeky Charlie smile, that masks will prevent contagions. In fact, the only masks that offer real protection are N95 masks or similar respirators. The popular cloth masks are of little more than symbolic value in preventing contagion.

Instructively, in Norway, which has had among the lowest incidence of Covid-19 in Europe, but where case numbers have increased in recent weeks, the latest national measures do not include a requirement to wear masks in public, although this option is left open to municipal authorities in the event of high infection levels.

Yet in Ireland journalists and ‘social influencers’ have accepted as self-evident that masks are a form of panacea; failing to recongise that approach is not backed by experimental data, and is in fact the lowest form of evidence.

Now armed with the received wisdom – mumbling ‘I follow the science’ – righteous members of the public are on the lookout for slackers, and woe betide anyone not wearing a mask when shopping or travelling on public transport; it has reached a point of such absurdity that some even wear them while alone in their cars.

But you might ask: what is the cost apart from mild to medium, or even extreme, discomfort, depending on how long it has to be worn? And as most of us don’t have to wear them other than when we enter shops then what of it?

Masks hide our faces so that we have difficulty recognising and communicating with each other. Indeed, our brains have evolved to recognise faces. We see faces in clouds, bushes and cracked tiling, a phenomena called pareidolia. I have yet to hear of such an occurrence where the face is obscured by a mask.

Pareidolia

Our face has a remarkable forty-two muscles and is the site from which we deliver most of our body language. Ask a mother of a new born to stare at her child without changing her facial expression for more than a few moments and the baby will become distressed and cry. This is how hardwired our need is to read faces.

Facial coverings – called surgical masks for good reason – are useful in clinical settings to prevent bacteria, hair, skin cells and mucus from falling into open wounds, but hardly when worn by unruly schoolchildren in class. The best reason to wear one now is simply to make people comfortable who believe they confer protection.

Asians, have worn masks for various cultural and environmental reasons, including non-medical ones, for decades. In Japan people who feel ‘under the weather’ wear them to be polite.

But there is no reliable scientific evidence to support widespread use, as Professor Carl Heneghan of Oxford University pointed out to the Dáil Committee on Covid-19 Response. There have only been three registered trials on the use of masks in the community: one in Denmark, one in Guinea Bissau and one in India – but none have reported outcomes so far.

Now let us for a moment indulge in that age old technique of the thought experiment. Viruses are measured in nanometres. If we looked at the material from which most of these facial coverings are made under an electron microscope we would see more holes than material.

A virus leaving your mouth, journeying out into the big bad world, is like a football passing through your front door. The football could hit the door frame and bounce back, but this is unlikely. The pseudo-scientific argument is that the virus travels first class in a large globule of spit and this globule gets jammed in the doorway, “proving” the efficacy of masks.

Ahh, but wait a minute, mask are often worn for hours by kids and cashiers in shops, so what about all the other graduating viruses and their globular carriages? I doubt they are all just clinging for dear life on to the mask for fear of upsetting the Irish expert.

Instead the globule eventually evaporates, after all it is mostly water vapour, the front of the mask dries and the viruses, being virtually weightless, just waft off on their merciless way.

Other Approaches

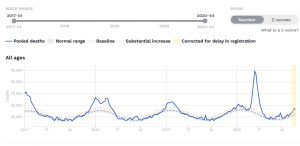

Now when I hear the mantra ‘wash your hands, social distance and wear a mask,’ I consider: are we running the risk of undermining our society to preserve some cherished scientific authority? We are supposed to be entering the second wave of a pandemic, yet while hospitals in countries such as Italy are under severe pressure – as was the case last February – few Europeans countries are now showing excess deaths. Yet the doomsday models that were wildly inaccurate last time around are being revisited.

Excess mortality in Europe source since 2017: https://www.euromomo.eu/graphs-and-maps/#excess-mortality

Shouldn’t our health authorities, especially in Ireland – which has had among the most stringent measures in the world throughout the pandemic – also be conscious of maintaining our humanity, and recognising the huge value – in terms of our health and wellbeing – of being able to gather, kiss, hug, talk, sing and laugh with abandon, without fear of breaking the law? We especially need to explain to our children that the world they currently live through is not going in a normal phase.

In preventing infections with a respiratory disease such as Covid-19, we might look back on what the great American polymath and Founding Father Benjamin Franklin once observed:

From many years’ observations on myself and others, I am persuaded we are on a wrong scent in supposing moist or cold air, the cause of that disorder we call a cold. Some unknown quality in the air may perhaps produce colds, as in the influenza, but generally, I apprehend they are the effect of too full living in proportion to our exercise.

Franklin observed a connection between succumbing to an infectious disease and poor dietary choices (“too full living”) and a lack of physical exercise that contributes to obesity, which we know significantly increases the likelihood of death from Covid-19.

He also had the following to say on the benefits of being outside into the fresh air:

I hope that after, having discovered the benefit of fresh and cool air applied to the sick, people will begin to suspect that possibly it may do no harm to the well. I have long been satisfied from observation, that besides the general colds now termed influenza (which may possibly spread by contagion, as well as by a particular quality of the air), people often catch cold from one another when shut up together in close rooms, coaches, et cetera, and when sitting near and conversing so as to breathe in each other’s transpiration, the disorder being in a certain state.

During this pandemic, and moving forward, we should thus be addressing a pre-existing obesity pandemic that is being exacerbated by some of the current restrictions on sports especially. Franklin also seemed to have recognised the importance of adequate ventilation in buildings.

Image (c) Daniele Idini

Thus addressing the underlying conditions exacerbating the Covid-19 pandemic may prove to be the optimum response, as the editor of The Lancet Richard Horton has argued:

we must confront the fact that we are taking a far too narrow approach to managing this outbreak of a new coronavirus. We have viewed the cause of this crisis as an infectious disease. All of our interventions have focused on cutting lines of viral transmission, thereby controlling the spread of the pathogen. The “science” that has guided governments has been driven mostly by epidemic modellers and infectious disease specialists, who understandably frame the present health emergency in centuries-old terms of plague. But what we have learned so far tells us that the story of COVID-19 is not so simple. Two categories of disease are interacting within specific populations—infection with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and an array of non-communicable diseases (NCDs). These conditions are clustering within social groups according to patterns of inequality deeply embedded in our societies. The aggregation of these diseases on a background of social and economic disparity exacerbates the adverse effects of each separate disease. COVID-19 is not a pandemic. It is a syndemic. The syndemic nature of the threat we face means that a more nuanced approach is needed if we are to protect the health of our communities.