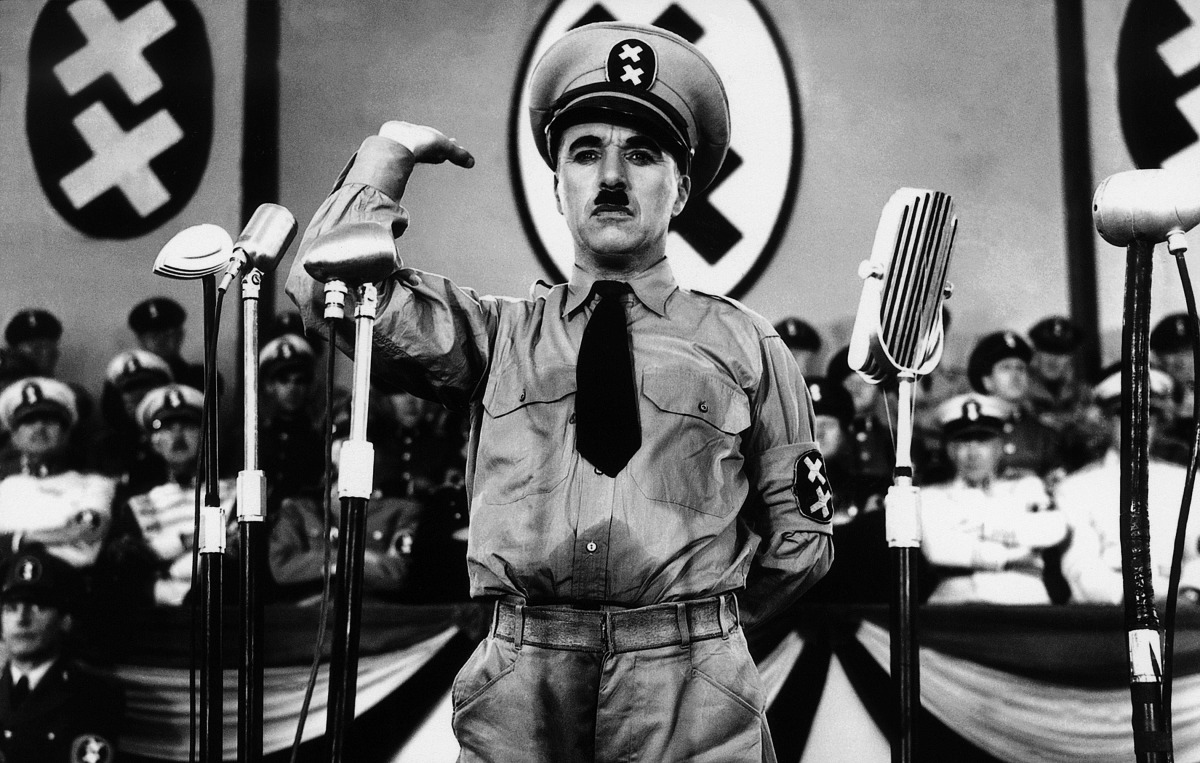

Don’t you ever read the papers? Roderick Spode is the founder and head of the Saviours of Britain, a Fascist organization better known as the Black Shorts. His general idea, if he doesn’t get knocked on the head with a bottle in one of the frequent brawls in which he and his followers indulge, is to make himself a Dictator.’ ‘Well, I’m blowed!’ I was astounded at my keenness of perception. The moment I had set eyes on Spode, if you remember, I had said to myself ‘What Ho! A Dictator!’ and a Dictator he had proved to be. I could not have made a better shot, if I had been one of those detectives who see a chap walking along the street and deduce that he is a retired manufacturer of poppet valves named Robinson with rheumatism in one arm, living at Clapham. ‘Well, I’m dashed! I thought he was something of that sort. That chin…Those eyes…And, for the matter of that, that moustache. When you say “shorts,” you mean “shirts,” of course.’ ‘No. By the time Spode formed his association, there were no shirts left. He and his adherents wear black shorts.’ ‘Footer bags, you mean?’ ‘Yes.’ ‘How perfectly foul.

P.G. Wodehouse, The Code of the Woosters (1938).

The above quote may offer a certain hope for those of us who see in each crisis a foretaste of worse to come; that hope is that Fascism can be undermined by ridicule – even while it is gaining traction – as long as a Dworkinian right to freedom of speech abides.

But I next turn to a writer not noted for his sense of humour, George Orwell, who is central to our understanding the Great Depression, at least from a British vantage. His 1946 essay ‘How the Poor Die’ is a also crucial text for this austerity period, when social supports are being steadily withdrawn and a public health crisis looms large. Such are the consequences, unintended or otherwise, of an awful ideology that has put the NHS into freefall, and the Irish health service into near collapse.

Animal Farm and 1984, with their simplification of language and distortion of truth from 2 =2 =5 to Newspeak – or in present parlance News International – are curiously prescient for our age. The Communist dystopia Orwell envisaged is not what we have now. Our own is of a different character altogether.

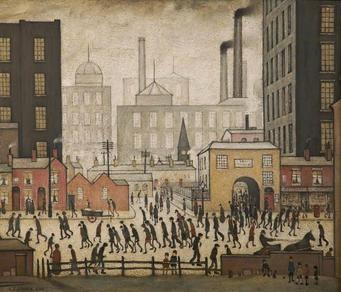

Lowry, Laurence Stephen; Coming from the Mill; The L. S. Lowry Collection; http://www.artuk.org/artworks/coming-from-the-mill-162324

Army of Managers

The great painter of the Depression-era L.S. Lowry once remarked:

A really efficient totalitarian state would be one in which the all-powerful executive of political bosses and their army of managers control a population of slaves who do not have to be coerced, because they love their servitude.

This is the kind of Stockholm Syndrome that we have witnessed throughout the pandemic, when even left wing parties previously noted for their resistance to corporate authority, rolled over to have their bellies tickled, as the one percent almost doubled their wealth.

Lowry, as much as Grosz and Dix, chronicled working-class existences in painting, but as a prose artist he also captured the era beautifully in Coming From the Mill (1930). ‘As I left [Pendlebury] station I saw the Acme Spinning Company’s mill,’ Lowry would later recall. Describing:

The huge black framework of rows of yellow-lit windows standing up against the sad, damp charged afternoon sky. The mill was turning out hundreds of little pinched, black figures, heads bent down. I watched this scene – which I’d looked at many times without seeing – with rapture.

His matchstick men and women are best seen in the Lowry Gallery in Salford near Manchester, an area much gentrified now but still recognisably working class. And if you turn away from the main paintings, one still finds the bitter fruits of economic depressions: drunken brawls and young children in virtual rags.

@DLangwallner rejects the motion that 'the Covid pandemic demonstrates that we should prioritise security and safety over individual liberty’, at the ESU, Dartmouth House, London on Sunday, 27th of October, 2022.https://t.co/JRD3foErZy@broadsheet_ie @danieleidiniph1 @BowesChay

— CassandraVoices (@VoicesCassandra) February 28, 2022

Brave New World!

Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World (1932) is a core text of our time. The soma-induced compliance replicates our non-critical consensus of disinformation. Bernard the anti-hero wishes to leave for Iceland, a psychological state many of us wish to flee to now. Like Wittgenstein, I have a preference for a good Fjord.

In mainland Europe the contradictions of the European Depression are well etched by the greatest of all American writers, F. Scott Fitzgerald. He was an incurable alcoholic by the time he penned his second masterpiece Tender Is the Night, to mixed reviews, in 1934. The lead character Diver is redolent of a lost parvenu generation, a parable for how many of a certain class lose their way on the French Riviera.

It is cautionary tale of a loss of relevance, context and credibility. In a way, we all must resist a decadent urge to act like Tory grandees on the fiddle amidst the booze at Number 10.

And what about other European literature for those who want us to “stay safe by staying apart”? Well, the antisemitic Louis-Ferdinand Céline is responsible for at least two prose masterpieces of the Great Depression that lay bay his own hypocrisy.

His 1932 Journey to The End of Night is a phantasmatic horror story chronicling the Great Depression. It contains a piquant quote that goes some way towards explaining his own moral descent: ‘I warn you that when the princes of this world start loving you it means they are going to grind you up into battle sausage.’ We ought to be wary of artists that achieve great success in their own time, or journalists for that matter.

He also refers to the “necessary” distance the rich must develop from the sufferings of the poor:

I hadn’t found out, yet that humankind consists of two quite different races, the rich and the poor. It took me … and plenty of other people . . . twenty years and the war to learn to stick to my class and ask the price of things before touching them, let alone setting my heart on them.

Jean Renoir

More than Céline, along with Albert Camus, the greatest French intellectual artist of that period was the film director Jean Renoir. His most significant film ‘La Règle du jeu’ is situated at the precipice of collapse.

Set in an aristocratic milieu just before the outbreak of the Second World War, it is decidedly jittery, with a real sense of fin de siècle. We find attractive though silly people on the brink of a calamity. It seems now quite relevant as we face unprecedented times, where chaos and uncertainty rule.

Renoir views the characters sympathetically with Octavia – the voice of moderation – central to the film. Renoir was acutely conscious of being on the brink of disaster, and expressed an objective humanism with the famous line ‘that everyone has his reasons.’

In the subjectivity of our time that quote remains a clarion call for a heightened perception of danger, especially as moral relativism gains traction.

Renoir elaborated in commentary on the film that all cultures are cliquish and have their own rules and protocols of dealing with those who do not observe the rules of the game, or the rule of law. But that is prior to seismic change where brute force supersedes civility.

Renoir touched a raw nerve. When it opened a right-wing French audience went berserk, in a way similar to the reception in the Abbey Theatre in Dublin to J.M. Synge’s The Playboy of The Western World in 1907.

Renoir’s acid comment was in effect that these people were doomed, and that the audience reaction showed that ‘people who commit suicide do not do so in front of witnesses.’

The film has an astute sense that class or poverty more than race or ethnicity is the ultimate determinant of social division. That idea remains vitally important in these absurd politically correct times, and indeed victimhood or assumed victimhood as it is now. Our priorities should be to maintain access to housing, health care and legal representation.

Welles and Buñuel

Another of the greatest creative artist of the twentieth century toured around Ireland at the end of the Depression, before taking a job at The Gate Theatre. Later, in ‘The Third Man’ (1949) he made a guest appearance as Harry Lime. One, less celebrated speech. captures the existential dilemma of our time

If I offered you twenty thousand pounds for every dot that stopped, would you really, old man, tell me to keep my money, or would you calculate how many dots you could afford to spare? Free of income tax, old man. Free of income tax – the only way you can save money nowadays.

This is a logic that appears to have been adopted by pharmaceutical companies in recent times.

The great surrealist film maker Luis Buñuel was another of the great anti-fascist artist of the Depression-era. He attacked the prevailing mores of clerics, sexual repression and state authoritarianism with utter clarity and savage wit. This led, unsurprisingly, to periods of exile from Spain and a final hideaway for eighteen years in Mexico.

The stunning and very brave 1950 film about poverty and child criminality in Mexico ‘Los Olvidados’ (the Forgotten Ones) caused a sensation at the time. Its theme reflects a drift into criminality among the youth in many parts of London and Dublin. Today’s child poverty, exploitation, crime and even slavery were also a feature of the Great Depression era.

Tell Me Why?

How does Fascism come about? Well it’s a product of inequality and poverty. You could say: “It’s the economy dummy!” In the period we can find evidence of this emerging among the workers in Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle, or the disenfranchised on the streets of Weimar, or the representations of Orwell and Céline who suffer most due to the naked expropriation “adults in the room.”

Economic depressions create conditions for fascism, or even the new-fangled corporate fascism of our age which represents a triumph of demagoguery and disinformation. So be wary of manipulation and stay flexible, if not unsafe. Facebook and the mass media augment Orwellian tendencies and a campaign of compliance and of induced consent is creating serf capitalism and a potential Malthusian population cull.

Alas, there is no New Deal or Marshall Plan on the horizon. World leadership is lacking and often far from benign and corporate-led. Apart from resisting manipulation, what all of us at the sharp end of the stick can do is protest to avoid obliteration and not be participants in our own self-abnegation.

Resist decadence if you can. Survive the new depression: this Great Reset Depression. It will require optimum coping skills not to be culled. And if all else fails, poke fun at the fascists and observe how uncomfortable they become.