In the controversy surrounding the leaking of a confidential document by then Taoiseach Leo Varadkar last year, a key point has been missed regarding whistleblower Chay Bowes’s motivations. As an insider and former head of the VHI Homecare division Bowes gained significant insights into the operation of the Irish health system, especially the HSE. This interview probes into the obstacles he faced in attempting to deliver an effective model of community care away from overcrowded hospitals. He argues the HSE perpetuates dysfunction to the benefit of the private system.

Daniele Idini explores continued challenges for Irish whistleblowers and interviews human rights lawyer David Langwallner now working on a private members bill.https://t.co/xDNigyJenY@BowesChay @paddycosgrave @j_reilly33 @broadsheet_ie @VillageMagIRE @WhistleIRL @PeterDooleyDUB

— CassandraVoices (@VoicesCassandra) June 30, 2021

Innovator

Chay Bowes first interfaced with medicine through the Irish Army Medical Corps in 1988. This stoked a passion for healthcare which led him to take up a job as a phlebotomist, where he encountered an older generation of hospitals, such as St James’s, where he worked with elderly patients in the country’s public health system.

This experience coloured his view of the health system as it evolved to become, as he puts it, ‘more focused on financial outcome rather than patient outcome,’ and led him to set up his own company, focused on clinical work in people’s homes.

He had found that general hospitals tended to be ‘Victorian constructs, where we put all the sick people who are susceptible to infections, so that they can mix with other sick people.’ He concluded ‘that much of what happens in the hospitals doesn’t really need to happen there, and a huge volume of those patients could be treated at home in a cheaper and safer holistic fashion.’

After the dismantling of small, community hospitals Bowes observed ‘pressure building on the larger general hospitals to become the catchall for all kinds of diseases and complexities,’ and that this ‘contributed to the ongoing perpetual dysfunction which is today what we call the HSE.’

Taking out a bank loan, he purchased a van to move around the nursing homes, taking blood samples. By that stage he had observed thousands of elderly arriving into hospital in taxis and ambulances for routine blood samples. There they were catching flus and colds, so he said to himself: “why don’t I develop a system to treat those people out in the community?” This was back in 2004-2005, but he was told that’s not how things are done.

Undeterred, he decided to take an extended leave of absence from the hospital to set up a service doing these blood tests in the community, which proved very successful. The only limitation was that he was working alone.

At that point, he expanded his service to give vaccinations in the community too and took on a few employees. The first company evolved into another, leading to a contract with the HSE in 2007 worth €14 million. That business was focused on patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and chest diseases. Its rationale was to keep various types of patients in the community, who were repeatedly being admitted to hospital with lung diseases.

‘So, they didn’t go into a hospital, where people tend to get sicker, particularly those with lung diseases. It also helped these patients,’ he says, ‘that their social networks were intact.’ Soon there were two hundred working for the company.

Resuscitation room bed after a trauma intervention.

Tara Healthcare

At that point he brought Dr. Gerry McElvaney on board, ‘a really patient focused guy,’ he says, ‘who was highly intelligent and super-committed to doing things differently.’

Together, they pushed forward with what became Tara Healthcare. When patients were surveyed, he says, ‘ninety-eight percent preferred to remain in the community under our scheme rather than go into hospital: all the data was saying that this was a much safer.’ It was also cheaper to deliver, and the patients’ families were delighted to remain with their loved ones.’

He argues that they had created a perfect example of how a community-based scheme could be delivered cheaper with better patient outcomes, and where staff were really happy too, as they could get out of the acute hospitals.

However, he encountered, ‘an incredible level of scepticism around innovation in Irish healthcare.’ In one case, he says, there was a hospital in Dublin, which ‘wouldn’t send patients to this new service, because they didn’t like our medical director because he came from another hospital group. Professional rivalry is rife in Irish Medicine, sometimes to the detriment of patients.’

HSE Logic

Time and again he was met with the perverse HSE logic of ‘it’s doing really well, so let’s shut it down and send all these patients back into the hospital.’

The HSE’s reaction to the Financial Crisis of 2008 was just like its dysfunctional approach to COVID-19 he argues. They closed his operation down because hospitals ‘which were in perpetual crisis wanted us to move this service into their area.’ A senior HSE figure told him directly that ‘“what you’ve done in Dublin is almost too good. Everyone’s going to want it. They’re going to want it in Galway. They’re going to want it in Limerick” So, they wouldn’t fund it because they were already funding the dysfunction.’

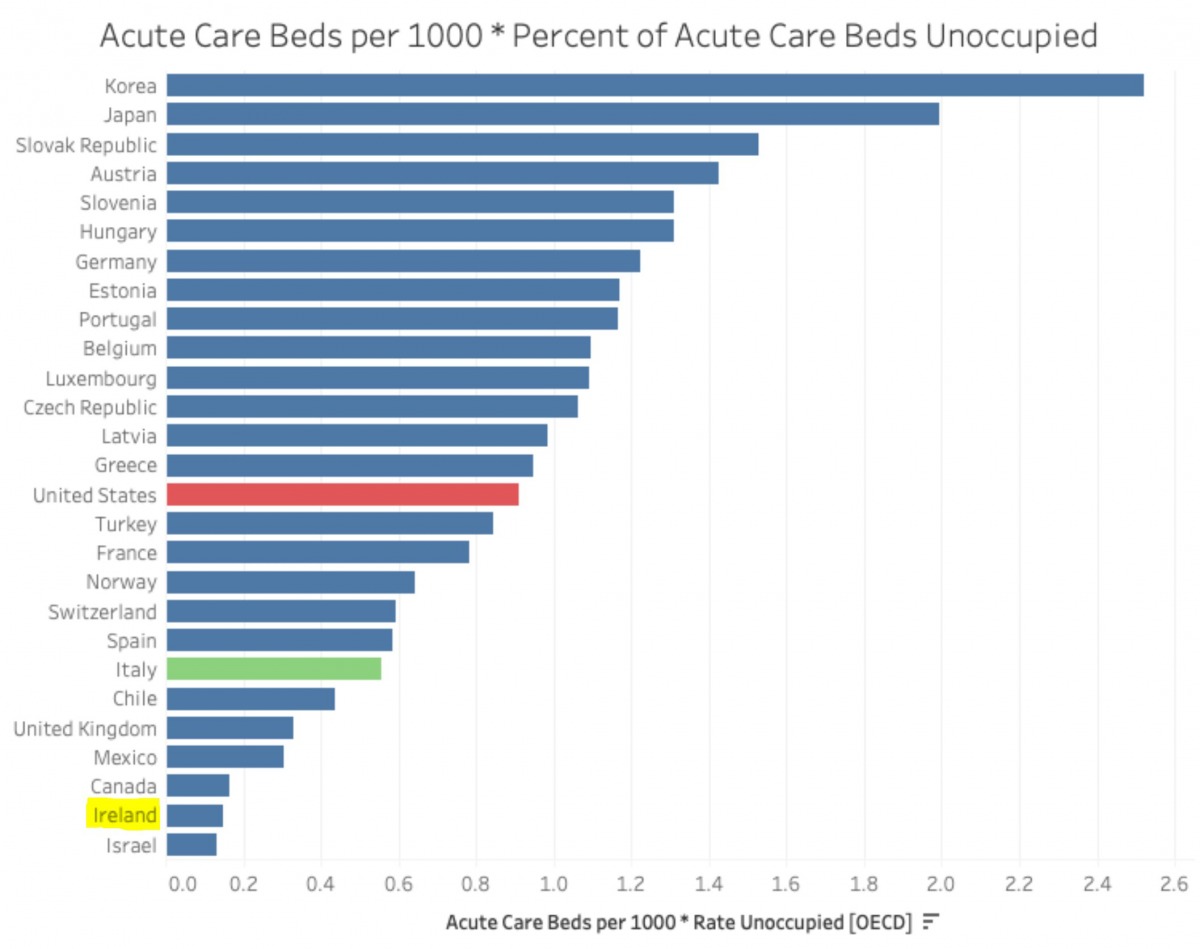

Acute beds per capita in Ireland, March, 2020. Source: https://twitter.com/kevcunningham/status/1245060194356379648/photo/1

Essentially, Bowes argues:

The agency funds the dysfunction to a certain level of service with tens of billions of euros. And when something outside of the system comes along and demonstrates efficacy, financial viability, and good patient outcomes, that’s irrelevant because they still have to fund the dysfunction. It’s like trying to repair an airliner in mid-air – you don’t want to land because it could expose the rottenness of the system.

So, we sent the patients back to hospital, further highlighting the dysfunction of the HSE at the time. They had to pay us a penalty for terminating the contract prematurely, which cost them more than running it for the subsequent two years.

Working for the HSE he found innovation was met with suspicion: ‘the hospitals want to hold onto patients because without patients occupying beds, they can’t justify their budgets.’

And because budgets are pinned to occupancy and the size of the facility, hospitals seemed slow to manage overcrowding at the cost of lesser funding.

Fair Deal?

He argues that we should ‘evolve to a place where we simply don’t treat people with certain uncomplicated infections in hospitals, like in Canada and Australia.’

Now, he says, the only fast track for vulnerable patients is into a state or private nursing home, which is excessively expensive, ‘or their home is taken from them in what the government very cynically calls a Fair Deal:

someone works all their life, pays taxes, builds a home for their family, and contributes to the state and to society. But when they get ill, go into a nursing home or require dignified care the state wants to take their home from them to pay for that care.

Moreover, despite earning huge praise from patients, peers and when he presented the scheme to the NHS in the UK, he found the HSE ‘were always finding fault with what we were doing.’

‘I became used to that,’ he says ‘and very quickly realized the only thing the Irish public system does very well is perpetual dysfunction. It manages to procure massive budgets from the State, and despite this consistently overspends,’ despite ‘terrible outcomes for patients.’

He suggests that it takes ‘a concerted effort to continually do health as badly as we do in Ireland’, a system of public health, ‘with such huge budgets for such a small population.’

He says it is important to question why, given a very small and young population, ‘half of that population pays out of pocket expenses, approaching €2 billion, for private health insurance.’ He reckons this is ‘to protect ourselves from the dysfunction of the public system.’

🚨A record 908,519 people in Ireland are now on some form of a public hospital waiting list to be treated or assessed by a consultant. Meanwhile Gov lacks meaningful action on addressing capacity deficits #CareCantWait @DonnellyStephen @mmcgrathtd https://t.co/8ye5e4DoWw

— IHCA (@IHCA_IE) August 21, 2021

Knock, Knock

‘It’s a very simple problem,’ he says, ‘too many of the same actors are involved in the public and private systems.’ The analogy he uses is of two separate doorways in a clinic: the public and the private:

You knock on the public door, and say, “Look, doc, I’ve got a terrible hip. It’s really hurting me. And he goes: “Yeah, you need a relatively simple, hip replacement, but it’s going to be probably three, three and-a-half years, because the system is overloaded.”

But the doctor adds unless of course you’ve got health insurance. So you say, “OK, I’ll go and get health insurance.” But by this stage you are too old to avail of this. But what are you going to do now, as your hip is only going to get worse?

You’ve been to the first door, where you met the doctor in the public system about the hip, who we’ll refer to as Dr Jim. Then you go ten feet down the corridor and knock on the door. “Who’s there? Why it’s Dr Jim again!’” And you say “Hey, Dr Jim, you just told me that you couldn’t fix my hip for three years.” and he responds: “not exactly. I can fix it if you pay me via your insurer.”

In a country of five million people, we have almost one million people waiting for care of one sort or another in a public system, which is one of the best funded systems in the developed world.

And, Bowes says, ‘it just so happens that the man running the show, Paul Reid, has no specific health care experience, for example. The UK’s NHS employs around 1.4 million people to serve a population of nearly 67 million. Its CEO Simon Stevens is paid €210,000 a year, while Ireland’s HSE employs around 102,000 people with a population of only 4.9 million, Reid is astoundingly paid over €426,000 a year.’

We have hundreds of people who work for the agency on long term sick leave. The dysfunction runs into every fractional part, IT, training, resourcing, recruitment, and services. The dysfunction is almost at a cellular level. But again, we are consistently told that we can’t land the jumbo jet to fix it, because if we do that, what will happen?

COVID-19

When COVID-19 landed, Bowes says, ‘with the stroke of a pen, we bought up every single private bed in the State. This occurred despite people saying since the foundation of the State, “Oh, you know, you can’t publicize the private, it would never work, but it was done overnight because the will existed.’

Health policy in Ireland, he says, reflects:

the laissez faire attitude of a class of people who are running the medical system, advising the agency and the legal system. They of course all have health insurance. I don’t know anybody who served on the board of the VHI or any doctor working in the system who doesn’t have private healthcare. I myself have to admit that I took out private health insurance purely because I know how difficult it is to access care via the public system. It’s sad but true and I am lucky enough to be able to pay, unlike more than 50% of the most needy In our society who cannot.

‘Irish People’ he says are dying ‘for the lack of basic diagnostic care.

Bowes muses on how: ‘The further up the pyramid you go around a health product in Ireland, the less you hear about the patients. And when you get to the board level, patient outcomes are in some way superfluous to the real issues, which are profit and the market.’ He argues that there ‘isn’t a single private provider in the country here’ which ‘isn’t preoccupied with profit.’

He says:

We’re happy to ostensibly starve a public system and propagate a private system which is absolutely predatory on the dysfunction in the public system. And in many, many cases, the people providing the care in the public system also have been or currently are providing care in the private system.

That’s our medieval, dysfunction and immoral system. It’s actually, and I don’t use this term lightly, an apartheid system. We have a segregated, apartheid system in health care. It simply isn’t based on needs of the patients. Ok, obviously, if someone’s at death’s door, they’re going to get seen, but I’m talking about this grinding dysfunction, where both sides are nodding to each other as they pass each other in the night, knowing that it’s so wrong. It’s so wrong. There are super doctors out there, super surgeons, super nurses and staff operating in the health system. It’s definitely a case of lions being led by donkeys.

Really encouraged by response of a leading figure in Irish culture over the past 50 years.

"Daniele's interview with Fr.McVerry is classic.

Cassandra is rapidly becoming the most important vehicle for ideas in the land."

***@danieleidiniph1 @BowesChay https://t.co/7N1bz38X77— CassandraVoices (@VoicesCassandra) November 5, 2021

Staffing

Bowes muses ‘I have no problem with doctors wanting to make a decent living. You’ve got to pay people appropriately. But now we’re flooding the system with locums from overseas who are often poorly trained and have poor English and patient interaction skills .’

And points to another ‘incredible dysfunction, which is again, state sponsored.’

We train more doctors than any other country of our size in the world, but we export them to Australia, New Zealand and the UK. It costs the state a significant amount to train these guys, and then they can just catch a plane to Bondi Beach. Of course, we can’t force people to work here – no more that we can force a health care worker to take a vaccine – but there are ways to incentivize the system, and develop better methods of training doctors, because we still use the archaic Leaving Cert as the basis for deciding who we train as doctors.

He also wonders:

How is it that while we train more doctors than anyone else that we are importing more doctors and nurses than anyone else? Countries like the Philippines, India and others are being bled of their precious nursing and medical staff to come to Ireland to look after our sick. There’s something wrong, right? But in the Irish system nothing changes. No wants to take on the vested interests. No one wants to take on the big personalities in health care and medicine. The political nexus between medicine, law and politics in Ireland is so tight because of insular practices and local allegiances trumping national welfare with some of the biggest political donors and influencers being waist deep in the sector.

He wonders ‘Who’s going to challenge the vested interests and speak out for vulnerable patients? The CEO of the HSE? Absolutely not. The past CEOs of the HSE seem to be only good at one thing, which is saying, “We’re trying…” But they walk out at the end of the end of their contracts with a big pension and usually into guess where? Yes, you guessed it, the private sector.’

He reveals how ‘a former CEO of the agency said to my face that he was the most powerless man in the health system.’

Image (c) Daniele Idini

Dysfunction Funds Profit

Bowes wonders:

How can you operate a business with a hundred and twenty thousand employees and seem to be powerless to sack people for not delivering, or in many cases simply doing their job wrong? Where’s the accountability in that system?

And looking back on the foundation of the HSE in 2005 he wonders:

How can you amalgamate numerous health boards which are operating as satellites into a single “dynamic entity” and nobody loses their job? Not one manager is made redundant. Not one of them is even sanctioned.

How can a health system pay out tens and tens of millions in malpractice claims for egregious malpractice and incompetence in both governance and clinical care? For essentially killing women who are pregnant by denying them an abortion? By condemning young women to terrible life ending illness by failing to diagnose their cancers? How can you pay out these tens and tens of millions again and again, year after year, and nobody is sanctioned for it? How does that work?

It works because the dysfunction funds profit, and that profit is harvested by vulture funds, by private hospitals and private investors, by their legal advisors, some of whom don’t even pay taxes in this country, and who pays the price? The citizens that languish on public waiting lists accruing ill-health because they can’t pay for treatment. The man with the simple requirement for treatment, he’s invisible to the system, he is superfluous to the profit motive.

The poor he says have no bargaining power because:

the bargaining power is money and influence, and the people who have the influence to change the system are receiving huge salaries to manage and essentially perpetuate dysfunction. Again, the private system predates on the mismanagement of the public system. If it functioned there would be no need for a private system, right? Therefore, you have to wonder, who does the current dysfunction benefit? It’s an easy one: the private providers. But nobody who is of the machine is working against it. No one in Leinster House is saying to the CEO of the HSE: “What are you doing for your four hundred grand? We’ve got less intensive care beds per capita than Lithuania or Latvia. Two years into a pandemic, we still don’t have a dedicated COVID hospital which is just insane.

Apparatchiks of a state system who’ve worked, like Paul Reid in state jobs are seen as a safe bet. They’re nominated in as managers, managers of dysfunction, gatekeepers for their political sponsors and marked for future cushy roles on the private side of the wall.

Image (c) Daniele Idini.

Perpetual Crisis

He adds that ‘things like this mysterious and much vaunted “Cyber Attack”, which apparently “destroyed the abilities of the system” seem to be a perfect excuse to deflect from the internal failures of HSE management and external incompetence of its political masters.’

Bowes says: ’what I know, and anyone that has worked in the system knows, is that there was and is no viable system to attack.’ The HSE have ruminated for decades on the implantation of an electronic patient record: they have spent millions evaluating, re-evaluating, procrastinating, and failing to implement a viable solution.

Months after this “Attack”, you’re still running Windows 1998. Somebody needs to be held accountable.

But, he says: ‘the Minister doesn’t talk to the to the HSE, the relationships between the “Three Masters” of Health are utterly flawed, the Department of Health is cumbersome and cautious, the HSE is a lumbering leviathan with no real direction other than self-preservation, and the Minister is preoccupied with surviving a potentially career ending stint in the mire of the Irish Health system.’

Consider this, with such a huge annual Health budget and such poor outcomes for patients alongside such terrible value for money, the dysfunction and paying for it becomes central to the rational of the organisation. They actually need this dysfunction. Without the dysfunction, they’d be screwed because there would be an open accounting of what we’re doing in a system which is delivering horrendous results.

He also criticises Stephen Donnelly’s policy of giving more money to the National Treatment Purchase Fund, which sends public patient overseas for treatment, arguing that ‘this is not the same as a really equitable national health system where everybody gets treated on the basis of need.’

He says that people could argue that in a free-market economy if someone wants to purchase health insurance it’s up to them: ‘However, that’s different to paying almost half a million a year to a CEO to perpetuate a dysfunctional system.’

He says the HSE is only interested in crises, ‘in things like COVID’ and saying ‘but COVID is why the system is screwed, or we’re dealing with the cyber attack, which has caused this perpetual dysfunction, which is, you know, all entirely untrue.’

His conclusion is ‘the managers, architects and political apologists for the segregated and morally bankrupt system have done an exceptional job of screwing the Irish people out of their tax dollar and their rights to health and dignity. I’m not sure they are capable of doing anything else. It’s time to demolish and rebuild.’

Featured Image by Gareth Curtis