Like errant flames from the dying embers of a once great fire, there is much fakery to be found emanating from a previously proud tradition of public intellectualism in the U.K., and elsewhere. The English philosopher John Gray (1948-) is at least not one of the self-help gurus, such as Jordan Peterson, that have gained public attention and earned ample remuneration in the process.

We do not find in Gray’s work the resigned intellectual play-acting evident in many books randomly grappling with our universe, and which provide the kind of quotable flourishes that play well at north London dinner parties. He is the doyenne and most garlanded of U.K. intellectuals today and so demands engagement.

Gray is no worshiper at the alter of the Enlightenment or the humanist tradition. He does not believe it provides us with the coping mechanisms for our current challenges. Ultimately, he has little faith in the ability of civilization, or rationality, to overcome the barbarism of a liberal experiment riveted by self-contradiction.

In short, he sees, both historically and now, the extent to which human irrationality governs actions. Thus he is decidedly anti-utopian, an empiricist and pragmatist. He holds out little hope for the realisation of lofty objectives, such as we find among technological evangelists or Bible-belt Christians. This is a theme he explores in some detail in his book Black Mass [2007].

In fact, all forms of demonist eschatology, chiliasm or end of day’s nonsense is parsed thoroughly in the text, from religious fundamentalism to neo-conservativism, to Marxism and Nazism. Quite correctly he identifies Tony Blair as a neo-conservative.

Thin Veneer

One suspects Gray would endorse Lon Fuller’s remark in a different context about legality and civility providing a thin veneer of civilization if the underlying culture is barbaric. This covering is growing thinner by the day I would argue.

And yet – although he may beg to differ – he displays a residual fractured humanism, and embraces certain conservative values. In effect, he is a Tory of the old school, with modest liberal leanings; the sort of person who, although he writes for the New Statesman, would equally happily associate with Tory grandees. His Disraeli-esque conservatism is one I would share some common ground with.

He has thus embarked on a voyage of passage from an earlier more doctrinaire, Thatcherite conservatism. He no longer venerates a laissez faire approach to the economy, and seems to have recognised that that approach went seriously awry. He is a fellow-traveller in a way with Jonathan Sumption, who has also arrived at a modified conservatism on his own intellectual pilgrimage.

Rather than seismic shifts – in that very British way – Gray argues that change should arrive incrementally, with allowance for the exercise of individual responsibility.

He also argues for a bridge between conservatism and the green or environmental agenda. He expresses a desire to create a Burkean ‘community of souls’, preserving that which is good and noble. But this seems a forlorn hope given how the Antarctica icebergs are on the brink of collapse, and international accords are torn apart with a pandemic upon us.

Covid-19

In a recent article for The New Statesman John Gray argued that the Covid-19 pandemic is a turning point in history, which will bring lasting changes to human behaviour. This will see online interaction rather than face-to-face communication becoming the norm, and a Hobbesian state becoming ever more intrusive, and with people increasingly accepting of this.[i]

In his view the populace will submit to the imposition of increased control, permitting a gradual and imperceptible erosion of civil liberties.

In effect we may be seeing the arrival of a new society of unfreedom, and the arrival of a technological serfdom evident in China, where Bentham’s Panopticon is writ large. But also in Western countries we are seeing surveillance from private and public bodies covering all of society.

China: technological serfdom. Image: Dmytro Sidashev / Alamy Stock Photo

One advantage, however, of the ‘Great Pause, of quarantine, as he points out, is that it could lead to a recalibration of ideas and fresh thinking. In silence new thinking may occur. But in order for this to happen we must escape from the distraction of what Frank Armstrong describes as the ‘Doomsday Machines’: the smart phones that prevent us from realising our true selves.

As Fernando Pessoa put it: ‘only by methodically, obsessively cultivating our abilities to dream, analyse and attract can we prevent our personality from dissolving into nothing or identical to all the others.’ It is certainly time for reflection but the path that lies ahead is shrouded in uncertainty.’[ii]

Gaia Hypothesis

John Gray is a convert to James Lovelock’s Gaia Hypothesis that the Earth is a self-regulating organism which maintains the conditions for life on the planet. It is a word he invokes regularly, and without exclusively focusing on humans.

Indeed, Gray appears to have a uniformly negative view of human nature and human beings. In his seminal text Straw Dogs (2004) we are depicted as rapacious, destructive and transhumanist. I suspect he is even more of this view now. Yet he clings on to a belief in decency and the exercise of personal responsibility, and liberally urges for peaceful co-existence to prevail.

As a Green Conservative and an opponent of neo-liberalism, he cautions against what Greta Thunberg described as the fairy tale of growth-without-end, and recognises how this is destroying the planet, and making human lives impossible. The pursuit of profit for its own sake of profit has led human activities to spiral out of control.

Our planet on the brink. Image (c) Daniele Idini.

Malthusian

While I warm to his Gaian sympathies, there are more disturbing aspects to his ideas that I take issue with. He appears to venerate a Malthusian liquidation or winnowing of the human population in the aforementioned New Statesman article. If there are too many of us I wonder does he regard himself as expendable and surplus to requirements?

In fairness it is ultimately a point about human progress having to be off set against scarcity. Yet it is easy to be sanguine – or even blasé – about meltdown when you sit atop the academic food chain. Stoical acceptance of human absurdity is not what is needed right now. It is a time for action after reflection.

Gray may have glimpsed the gorgon’s head of the dangers we confront, but seems to shrink from urging the radical responses required. I suspect donnish privilege has softened the attack and brought a modus vivendi with these circumstances. After all, his own life has been a success by most measures, so he can at least take refuge in haughty disapproval, or at least he could prior to the Corona-pocalypse.

But of course, in the interests of fairness, his prescience should be noted in pointing out that dwindling planetary resources, and wealth inequalities, are undermining what we cherish, and accelerating Malthusian dynamics.

Any invocation of Thomas Malthus (1766-1834) nonetheless reminds me of Jonathan Swift’s indispensable ‘A Modest Proposal’ (1729). Swift responds to the genesis of the ideas that Malthus would go on to articulate with withering satire, expressed with deadpan seriousness: he promotes the consumption of babies as a way of solving the problem of over-population.

Gray walks the same Swiftian line – though without quite the panache – in an essay on torture in which he mocks liberal values. Tongue-firmly-planted-in-cheek, he argues torture potentially promotes human rights:

Self-evidently, there can be no right to attack basic human rights. therefore, once the proper legal procedures are in place, torturing terrorists cannot violate their rights. in fact in a truly liberal society, terrorists have an inalienable right to be tortured.[iii]

Religious Fundamentalism

I share Gray’s contempt for religious fundamentalism. He does not display the dogmatic atheism or extremism of Richard Dawkins or Christopher Hitchens, but allows for Christian worship in a tolerant way, and merely warns against barbarism, and end-of-day’s eschatological chiliasm.

Yet the solution in his new book of jettisoning both the sweet poetry of Genesis and secular humanism engenders in Seven Types of Atheism (2018) a rather denatured Arcadian spirituality, which is neither flesh nor fowl or even a guide to a more meaningful existence for the varied lives he believes we should lead.

It’s almost an intellectual Flake commercial, which tastes like religion never tasted before; although it should be acknowledged that he is resolutely anti-consumerist, and critical of the manufacture of insatiable desires. At one level he is arguing for makeshift true grit or graft to cope with unbounded irrationality. We must, he suggests, develop new patterns of living to cope with the new disorders and challenges we face.

Intellectual flake commercial.

He says anyone can live in a variety of ways, and I suppose we all do need to slow down and embrace both distraction and silence. But I believe the finality of total silence is always to be resisted – ‘Rage, rage against the dying of the light…’

The Good Life

There are many ways, Gray contends, of living well. Differing types of the good life, but he is insufficiently specific as to what these are.

With the changing world of work, and a lack of employment prospects for many, one suspects he has an overly optimistic understanding that whatever fulfils someone is what they ought to be doing, which is all well and good, but that doesn’t necessarily put supper on the table. I fear most of us will have to find different survival strategies to cope with our disposability in a world that cares for us less and less.

John Gray is reliably sceptical of junk science that is now crashing into us in ceaseless waves, most recently with Donald Trump’s proposal to inject disinfectant to prevent Covid-19.

Donald Trump throws out the idea of injecting disinfectant to kill the coronavirus during the White House press briefing https://t.co/U6rH0PwJkR pic.twitter.com/KDWlanFCRE

— Bloomberg (@business) April 24, 2020

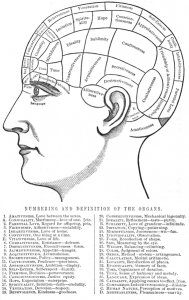

Phrenology.

A useful example Gray has provided is in the recrudescence of phrenology, where criminal patterns of future behaviour are derived from skull sizes, which feeds into racial stereotypes. Our criminal justice system, in allowing bad character admissions, has dangerous preludes of pre-crime and conviction by demonization.

It will take a brave leader, of men or opinion, in future to insist on civilized values. John Gray has intimated, and I agree, they will not matter.

In his esteem for silence to avoid distraction and enhance contemplation Gray comes across like the effete aristocrat in Turgenev’s Father and Sons, as the Bolsheviks steadily take control. But at least The New Statesman provide him with a platform, and the books continue to sell to a dwindling educated public.

Featured Image: Joseph Wright’s An Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump, 1768, National Gallery, London.

[i] John Gray, ‘Why this crisis is a turning point in history’, New Statesman, April 1st, 2020, https://www.newstatesman.com/international/2020/04/why-crisis-turning-point-history

[ii] Fernando Pessoa, The Book of Disquiet, translated from the Portuguese by Margaret Jull Costa, The Serpent’s Tail, London, 2017, p.107

[iii] John Gray, Gray’s Anatomy: Selected Writings, Penguin, London, p.222