Stanley Kubrick’s 1964 film ‘Dr Strangelove’ dramatizes the still not-altogether-remote scenario of Mutually Assured Destruction (MAD). It begins with a deranged U.S. Airforce General, Jack D. Ripper, overriding Executive Command and ordering a surprise nuclear attack on the Soviet Union. The Russians, unbeknownst to the Americans, have developed a deterrent – the Doomsday Machine – that automatically detonates, with devastating global effect, if a nuclear device explodes in Soviet territory.

Kubrick masterfully conveys the absurd conformism of a military organisation obeying orders to a point of self-annihilation. In the end, Major T. J. ‘King’ Kong, the B-52 commander delivering its payload, straddles the bomb, whooping as he descends to his own, and humanity’s, demise. Despite its apocalyptic message, the film remains enduringly hilarious, reflecting its alternative title: ‘How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb.’

A recent viewing in Dublin’s Lighthouse Cinema left me wondering, though, whether Kubrick derives too much comedy from an appalling vista we still confront. Laughter remains a safety valve, permitting an audience to carry on with business-as-usual, while the ultimate stupidity of nuclear war remains a real possibility. Are we, unconsciously, making light of President Donald Trump’s recent euphemistic warning of an ‘official end’ to Iran?[i] As Friedrich Nietzsche puts it: ‘in laughter all evil is compacted, but pronounced holy and free by its own blissfulness.’[ii] Regular doses of humour are one of life’s balms, but sometimes we laugh along to the exclusion of more serious engagement. Fittingly perhaps, the serious work of producing Cassandra Voices generally occurs in a studio above a crowded comedy club in the heart of Dublin, from where laughter often wafts upstairs!

If Iran wants to fight, that will be the official end of Iran. Never threaten the United States again!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) May 19, 2019

Millenarian doomsday scenarios have haunted humanity since time immemorial. A ‘Great Survey’ of England and Wales in 1086, used to ascertain the proportion of the national wealth owing to King William ‘the Conqueror’ (also less flatteringly known as ‘the Bastard’), was subsequently labelled the ‘Book of Domesday’ (Middle English for ‘Doomsday’). This accumulation of data in the hands of a monarchy had terrifying connotations at a time when many perceived the end of the world, and its Final Judgment, to be nigh.

Today humanity confronts varied doomsday scenarios – generally gleaned from scientific analysis rather than metaphysical speculation – with anthropogenic climate chaos, mass extinctions and the still unresolved danger of a nuclear Armageddon topping the list. We remain in many respects, in Carl Jung’s phrase, technological savages[iii], operating machinery with capacities far exceeding our wisdom as operators. It just takes one fat finger to push the button, or an unimpeded algorithm.

But perhaps it is not nuclear warheads, or even coal-powered stations, that represent the Doomsday Machines of our time. After all, humanity could quite easily seize control of its fate, elect reasonable leaders, bring about a Green New Deal and decommission nuclear weapons. So what is holding us back from taking the action required for the benefit of the great mass of our species, and the rest of the natural world? Another mechanism, operated by most adults in developed countries, is, I believe, befuddling our wits and deterring a collective shift in consciousness.

Developed simultaneously in the early 2000s by a number of manufacturers, the smart phone is replicating the Book of Domesday by tracking our movements and online preferences to the benefit of vested commercial interests, and shadowy state emanations.

Of greater concern, perhaps, than the hollowing out of our privacy is the addiction the vast majority of us have to the narcissistic, solipsistic and often pugilistic ‘social’ media of Instagram, Facebook, WhatsApp, Snapchat and Twitter, conveyed through apps on our smartphones. Staring into the void of communication-without-end from dawn-to-dusk, successive ‘hits’ are delivered, revealing who messages us, ‘likes’ our image or words, or offends us. Notably, Donald Trump is the acknowledged master of the soundbite Twitter update (maximum length two-hundred-and-eighty-characters), heralding the short-attention-span-politics evident in most countries.

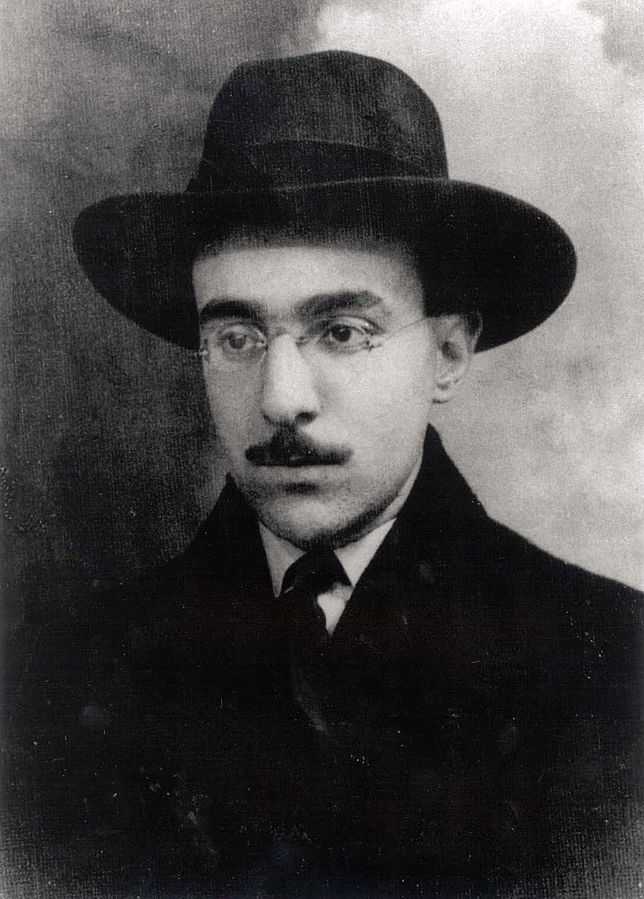

Social media is the thief of time and an agent of homogenisation. Writing in the early twentieth century, the

Fernando Pessoa 1888-1935

Portuguese poet Fernando Pessoa seemed to anticipate the contemporary malaise. ‘Given the metallic, barbarous age we live in,’ he wrote, ‘only by methodically, obsessively cultivating our abilities to dream, analyse and attract can we prevent our personality from dissolving into nothing or identical to all the others.’[iv]

The smartphone provides a simulacrum of varied technologies, such as an automated camera providing the semblance of a real one, but where the necessary application to understand the apparatus is no longer needed. The capacity to share easily what we have created has overtaken the creative process. The necessary isolation of the artist has been abandoned in favour of the instant hit of validation from our peers.

Likewise, through digital attenuation, music is debased and choice diminished when we succumb to the algorithms of Spotify and YouTube that are carried with us everywhere we go on our Doomsday Machines.

Of particular concern is a generation of teenagers who know of no other life other than that mediated by the Doomsday Machines. What is missing from their lives is the crucial ingredient of tedium, which again according to Pessoa is ‘that profound sense of the emptiness of things, out of which frustrated aspirations struggle free, a sense of thwarted longing arises and in the soul is sown the seed from which is born the mystic or the saint.’[v] Being bored can have its advantages.

I would like to say I had the willpower to renounce my own device, but as is so often the case in life, the end of the affair occurred by accident. Fiddling with its AMAZING properties, for the umpteenth time that day, as I double-jobbed playing with my young nephew, the Machine slipped from my grasp and hit a hard stone floor. The glass did not shatter exactly, except in one corner which felt the full impact, and from which a few glittery shards crumbled away. But, faintly detectable, three deathly cracks ran up from where it had landed, strangely mirroring the lifelines on my hand. When I tried to switch it on, all I found was a faint blinking light, which soon lapsed. Still looking sleek and powerful, though now veiled in a black hood of inoperativeness, it appeared to me like the corpse of a young soldier, handsome features intact, save for a bullet wound to the neck.

I felt deflated, angry and increasingly tetchy. How was I going to survive without it after a decade-long reliance? Like any addict, I felt pangs for the addled communication, information-gathering and idle scrolling that had become my early morning ritual, as I lay prostrate in bed.

As it transpired there was still some life in the Machine — I had simply smashed the screen, which I replaced at a reasonable price in a shop on Capel Street. But the liberation of a few days had changed my perspective. I had an unmistakable feeling of a great weight being lifted off me. In the meantime, I had purchased a ‘brick’ phone for next to nothing and now alternate between the two, only using the Doomsday Machine, now shorn of most, though not all, social media apps, when strictly necessary. I am a work in progress.

I know many people, more sensible than I, who have deleted all social media apps from their smartphones save for WhatsApp. This is, however, the Gateway Drug that maintains the addiction, leaving the impression that you cannot live without the Doomsday Machine. In a sinister twist, WhatsApp cannot be used on a laptop, for example, without already being connected to a Doomsday Machine.

Facebook has become the lightning rod for much of the bad press around social media – those pesky Russians again – and its distorted algorithm is a distinct nuisance if one is attempting to share meaningful content, as the cutesy image will always win out. Used strategically, however, it has its advantages, especially as a means of staying in contact with a large number of people, and for the purpose of events. It only really becomes problematic as an app on a smartphone that sends out regular notifications, prompting idly scrolling. I can live with it on my laptop, although I have given up on the hope of using it as a conduit for radical journalism.

As regards the confessional nature of posting our thoughts, I was struck by further prescient words from Pessoa: ‘What could anyone confess that would be worth anything or serve any useful purpose? What has happened to us has either happened to everyone or to us alone; if the former, it has no novelty value and if the latter it will be incomprehensible.’[vi] I am coming to recognise that most of the online outbursts I am prone to are perhaps better left unsaid.

Instagram offers a good medium for photographers to display their work, but is overwhelmingly narcissistic, not only through that ultimate expression of Doomsday Machines, the selfie, but also via the look-at-my-beautiful-life imagery that abounds. Planet Instagram is full of beautiful people who overcome life challenges, reveal plenty of tanned flesh and speak in a patois of hashtags.

Selfie by name.

Pessoa would take an uncompromising view:

Man should not be able to see his own face. Nothing is more terrible that that. Nature gave him the gift of being unable either to see his face or to look into his own eyes … he could only see his face in the waters of rivers and lakes. Even the posture he had to adopt to do so was symbolic. He had to bend down, to lower himself, in order to commit the ignominy of his seeing his own face … the creator of the mirror poisoned the human race.[vii]

There are times when access to the Internet while on the move is of great value. Google Maps makes travel immeasurably easier. But are we comfortable with all our movements being tracked? Smart-phone maps also reduce the sum total of our interactions with fellow human beings, and makes us less observant of the world around us.

A good rule of thumb is that, unless we are sitting upright, communication is unsatisfactory. The same applies to reading news sites – I had become all-too-prone to only partially reading articles. Indeed, the ‘most read’ articles on most sites tends to be prurient ‘click-bait.’

I suggest you forget about the hurried message and make time for real expression in communication. There is no point attempting to stay in touch with everyone, because it is impossible. Leave more time for reading books, making music, being present to friends and family, and allow space for the tedium that brings daydreaming.

The Internet can open new horizons of knowledge, bringing to fruition Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz’s (d. 1716) dream of a bibliotheca universalis, a ‘universal library’, where expert insight is available to all, everywhere. It could lead us into thinking more globally. But this beast needs considerable taming. Its great potential may be more easily realised by abandoning Doomsday Machines altogether. The wider consequences of a less mediated society could be profound. If enough of us can escape the clutches of the Machines, perhaps we can eventually develop the focus required for collective action.

Follow Frank Armstrong on Twitter

[i] Seung Min Kim, ‘Threats would mean ‘official end’ of Iran, Trump warns in tweet’, May 19th, 2019, Washington Post.

[ii] Friedrich Nietzsche, Thus Spoke Zarathustra, translated from the German by Graham Parkes, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2007, p.202.

[iii] See Laurens van der Post, Jung and the story of our time, Vintage, London, 1976, p.200

[iv] Fernando Pessoa, The Book of Disquiet, translated from the Portuguese by Margaret Jull Costa, The Serpent’s Tail, London, 2017, p.107

[v] Ibid, p.363

[vi] Ibid, p.197

[vii] Ibid, p.91