The Russian bear looms in the English-speaking imagination as savage and barbaric, but with a native cunning in need of taming. Throughout the nineteenth century British imperialists looked on their seemingly ursine counterparts with a mixture of dread and superiority. William Makepeace Thackery’s poem ‘The Legend Of St. Sophia Of Kioff’ (1855) contains a typical portrayal of their Asiatic barbarism:

Down they came, these ruthless Russians,

From their steppes, and woods, and fens,

For to levy contributions

On the peaceful citizens.

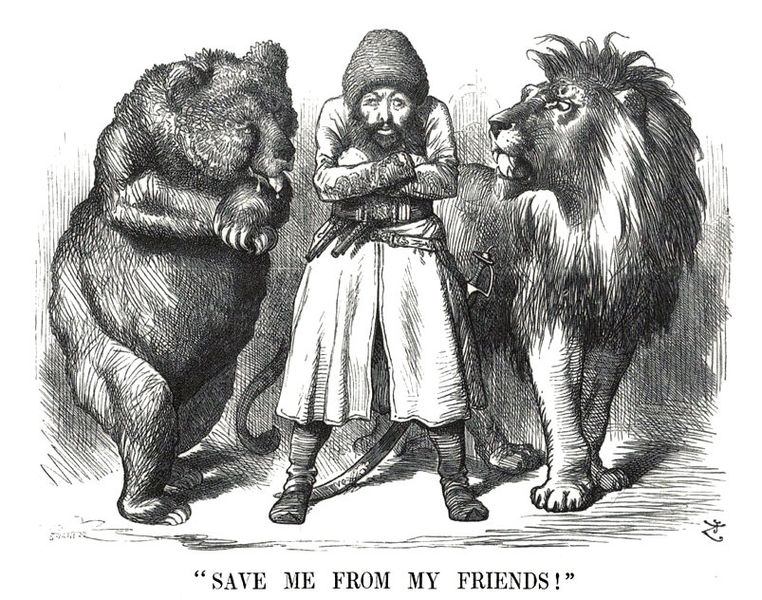

The ‘Great Game[i]’ of that time involved intrigues between British and Russians agents. India was the ultimate prize, with the ‘Near East’ forming part of an expansive theatre. Curbing Tsarist Russia’s encroachments brought British military expeditions into Central Asia. There they met the bellicose Afghans – who dished out one of the most ignominious defeats in British military history: the 1842 retreat from Kabul, when all but one European and a few Indian sepoys from Sir William Elphinstone’s 4,500-strong army limped back to base in Jalalabad.

Great Game Cartoon from 1878.

These colonial intrigues endowed the English language with a term now more commonly used in a sporting context: ‘pundit’, originating from the Sanskrit word ‘pandit’, meaning ‘knowledge owner’, or ‘learned man’. These local informants provided intelligence on the warlike peoples inhabiting the inhospitable terrain between lush India and the endless steppe. Tales were embellished to please the ear of the listener, moulding enduring Oriental stereotypes. Today’s pundits on international affairs also draw, perhaps unwittingly, on historic accounts, and are similarly prone to over-statement.

By Jingo

Nineteenth-century British Russophobia popularized the term ‘jingoism’, which can be traced to a song commonly sung in Victorian musical halls:

We don’t want to fight but by Jingo if we do,

We’ve got the ships, we’ve got the men, we’ve got the money too,

We’ve fought the Bear before, and while we’re Britons true,

The Russians shall not have Constantinople.

The Anglo-French victory in the Crimean War 1853-56 checked Russian designs on a Mediterranean port, but the dispute simmered, as Tsardom became a byword for tyranny – ironically, given the brutality of the simultaneously expanding British Empire. Projecting one’s worst characteristic onto to a remote ‘other’ is not restricted to individuals.

By the end of the nineteenth century British imperialists felt more secure in their hold over the ‘jewel in the crown’, and another, Teutonic, enemy had arisen, aspiring to weltmacht (‘world power’): Germany was upsetting the balance of power in Europe, and required containing.

Détente with Russia – which from 1891 had been in alliance with the French – followed, culminating in the Anglo-Russian Entente of 1907, and eventual alliance during World War I. Long before the unexpected Bolshevik Revolution of 1917, however, British policy makers were worrying about the consequences of a Russian victory on the Eastern Front.

These concerns reached fever pitch after the October Revolution, and the triumph of the Reds in the Russian Civil War, which included an unsuccessful intervention by Allied forces in support of the Whites. But by 1920 the Red Army was in command of most of the former Russian Empire, and had reached the gates of Warsaw. A shattered Germany, experiencing Communist insurgencies, lay ahead, before ‘the miracle of the Vistula’ – the victory of the Polish forces under Marshall Pilsudski, supported by the French. The Polish-Soviet conflict was resolved by the Treaty of Riga in 1921, bringing respite for two decades.

In the Western imagination, during the 1920s and 1930s the Russian menace merged with the Red Peril, and a layer of ideologically-driven ruthlessness was added to the character. American reactionaries used the scare to destroy the labour movements that were then making inroads. The clampdown on the American left involved draconian measures (instigated by, among others, a young J. Edgar Hoover) against ‘subversives’, such as five-time Socialist Party Presidential candidate Eugene Debs, sentenced in 1918 to a ten-year prison sentence for urging resistance to the military draft, later commuted to three years. The media played its part, including disseminating the forgery, ‘The Protocols of the Elders of Zion’, which established the myth of Jewish Bolshevism. America would bend principles where necessary to keep out the ‘Commies’.

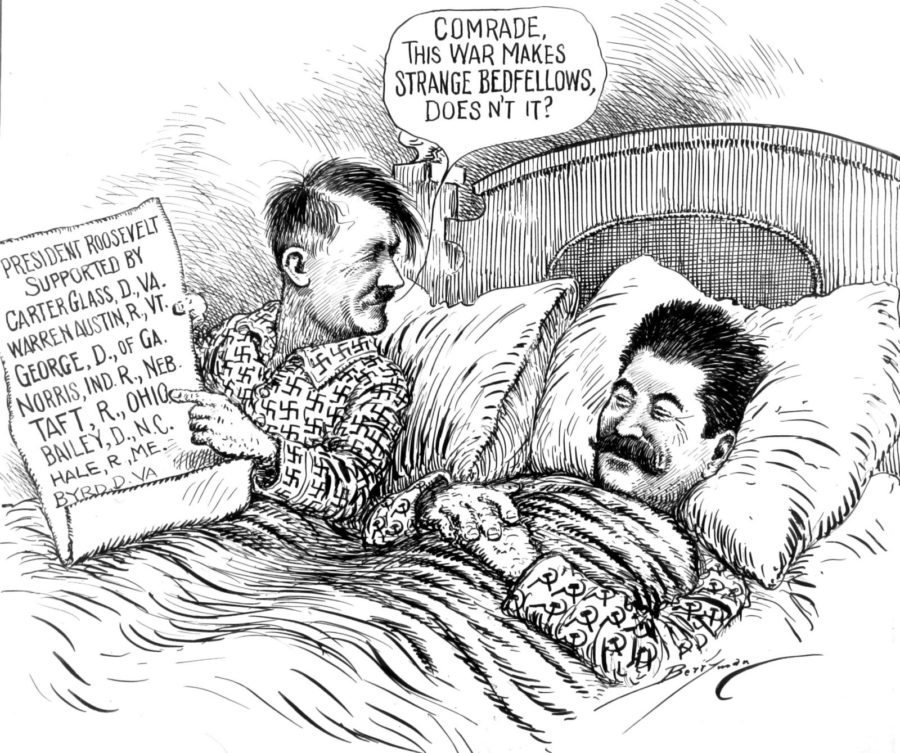

In Europe in 1939, the uneasy peace on the Eastern Front ended with the unlikely Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact between the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany, ushering in the fourth, and most savage, partition of Poland. Hitler repudiated that Pact in 1941, with Operation Barbarossa, the invasion of the Soviet Union. The ensuing alliance between Britain (and eventually the United States) with the Soviet Union decisively changed matters. The murderous Red Tsar, Joseph Stalin, was affectionately known as ‘Uncle Joe’, as long as the Nazi foe persisted.

Predictably, relations deteriorated rapidly again after the war – especially after the Berlin Blockade of 1948-49 – but the prospect of mutually assured destruction (MAD) brought a Cold War, lasting forty years.

John le Carré

From an imperialist perspective, World War II was a pyrrhic victory for Britain, which completed its metamorphosis from global hegemon to medium-sized client-state in the bipolar geopolitics of superpowers. The shambolic invasion of Suez of 1956 was the dying gasp of the British Empire, and the ‘winds of change’ swept through Africa during the 1960s.

To a large extent, the United States inherited Britain’s role as the world’s policeman, although the U.S. has shown greater reliance on proxies – ‘divide and conquer’ – the extension of ‘soft’, cultural power, and economic manipulation – with the Iraq and Vietnam Wars notable exceptions.

As part of a contiguous Anglosphere, the United States nonetheless inherited various tropes about a Russian ‘other’, extending back into the nineteenth century. The McCarthyite witch hunt in the 1950s against Communist sympathisers, especially in Hollywood, showed the U.S. at its most paranoid.

The excesses of the American intelligence services both internationally, through the CIA, and internally, through the FBI under its long-time director J. Edgar Hoover, are well documented. These included targeted assassinations, foreign coups and mind control experiments (the MKUltra project saw U.S. citizens being dosed with LSD, generally without their consent or knowledge). In any intelligence war, the U.S. could play just as dirty as its opponent.

In the latter half of the twentieth century a new layer to the Russian mystique was added by the Cold War literature of John le Carré, and other spy novelists. Karla, a recurring le Carré character, emerges as the archetypal devious, ruthless and ideologically driven Russian spymaster.

That is not to imply that the Soviet and successor Russian regime have not been villainous, and manipulative. According to Ben MacIntyre in his account of the extraordinary career of Oleg Gordievsky, a KGB officer who spied for the British, the KGB ‘had long excelled in the art of manufacturing ‘fake news’;’ taking ‘’active measures’ to influence public opinion’, and ‘sow disinformation where necessary’[ii].

But the organisation was also beset by money-grubbing corruption and institutional decay, especially as ideological fervour wavered in the great chill of the final decades before glasnost and perestroika, under Mikhail Gorbachev. After being posted to Copenhagen in the early 1970s, Gordievsky discovered that the recruitment of informants was ‘an invitation to corruption’, since most officers invented their interactions, falsified bills, ‘made up their reports and pocketed their allowances.’[iii] Upon being posted to London at the end of that decade he then found that most of the information sent back to Moscow by the heavy-drinking KGB bureau chief was ‘pure invention.’[iv]

The Russia of the Western imagination refuses to conform to reality. Indeed, the threat may be aggrandized by self-serving writers. It is in the interest of the powerful Military Industrial Complex, for U.S. society to remain on edge, at war-without-end. In one rare slip, Lockheed Martin Executive Vice-President Bruce Tanner revealed to a conference in 2015 that his company would see ‘indirect benefits’ from the ongoing war in Syria.[v]

Al-Jazeera reported that the ‘black budget’ of secret intelligence programmes alone was estimated at $52.6bn – under President Obama’s watch – in 2013. That was only for the secret programmes, not the far greater intelligence and counterintelligence budgets.[vi] These agencies at times use mouth pieces in the press, and academia. The import of information being released to the public by U.S. agencies competing for funding and survival surely requires careful analysis.

One former CIA station chief in the Middle East, characterised the diverging roles of the main agencies to the investigative reporter Seymour Hersh as follows: ‘Don’t you get it Sy? The FBI catches bank robbers. We rob banks … And the NSA? Do you really expect me to talk to dweebs with protractors in their pockets who are always looking down at their brown shoes.’[vii] U.S. spooks are every bit as manipulative, and far better funded, than their Russian equivalents in a discipline the former CIA spymaster James Jesus Angleton described as ‘the wilderness of mirrors’.

Vladimir Putin is not a mass murderer in the mould of a 1930s dictator, intent on imposing an inflexible ideology on the rest of the world. Crony capitalism or strongman rule could be used to describe his regime. Importatnly, his ambitions appear to be limited to restoring the territory of the Soviet Empire to Russia, rather than fomenting World War III.

The Russian President is probably best viewed as a Shakespearian villain, whose violent impulses, as Alexander Solzhenitsyn put it, ‘stop short at ten or so cadavers, because they have no ideology.’[viii] This offers scant consolation political prisoners in Russian prisons, but Putin has certainly shown no genocidal tendencies. Soviet technology has been in decline vis-à-vis the West since the 1960s, and with the breakup of the Union the rump Russian state lost important technological and industrial centres, such as Dnipropetrovsk in Ukraine; but the English-speaking world remains fixated on the threat.

Russia’s ‘strengths’

The academic author Timothy Snyder is a leading purveyor of Russian history, and mythology. In a recent interview he stated:

Throughout the Cold War, Russia was always better than us when it came to penetrating their enemies and breaking them down from within. Rather than smashing things overtly, they would work from behind the scenes to cast doubt on things. They’d insert their people into enemy organizations and slowly create chaos from inside. They’ve always excelled at turning people against each other.

The British, in particular, by the end of the Cold War had gained the upper hand over their Soviet counterparts, with their man in London’s KGB station feeding her Majesty’s government almost anything they would wanted to know, including that then Labour leader Michael Foot had been in the pay of the KGB until 1968.[ix] Gordievsky’s intelligence-gathering was of an enormous assistance in Margaret Thatcher’s (and Ronald Reagan’s) establishment of good relations with the reforming Mikhail Gorbachev. Also, by the early 1980s the CIA had over one hundred covert operations underway inside the Soviet Union, and at least twenty active spies.[x] Nonetheless Snyder insists on the fiction of an omniscient Soviet spymaster transitioning into a Russian web guru:

Russia lost the Cold War because the Cold War was decided by economics and technology; it was a material competition. But after the Cold War, we moved into a different world, a world defined by the internet, and that’s a much more psychological world. The techniques they’ve been honing for decades are much more powerful in this new digital world, where emotion dominates and everyone is connected and there is so much information floating around. This is a world of information warfare, and that suits Russia’s strengths.[xi]

Snyder’s anachronistic generalisations about the Russian character belie the distinction between the ideologically-driven Communists under the Soviet Union, especially prior to the Prague Spring of 1968, and the more venal aspirations of the successor Russian regime.

One academic review of his recent book (The Road to Unfreedom: Russia, Europe, America, New York, Tim Duggan Books, 2018), portraying Putin as a latter-day Nazi, sets the record straight:

The fact that Timothy Snyder is an influential public intellectual and respected historian is no reason for scholars not to challenge his facile and polemical analysis of the contemporary Russian state. By obfuscating the broad debate on Russia, Snyder denies the need for a serious, unbiased analysis of those features of the Putin regime that could be characterized as fascist. Distortions, inaccuracies, and selective interpretations do not help illuminate what motivates the Russian leadership’s self-positioning on the international, and in particular the European, scene. Simplistic reductionist techniques and invalid reasoning further confuse the analysis—and bias policy responses.[xii]

Snyder’s polemics appeal to the mass media market, and “bias policy responses”. It is as if failings in our own civilisation appear to demand external explanation.

Timothy Snyder, historian and author, teaching at Yale university in 2017.

‘The Russia in ourselves’

In his account of the career of Carl Jung, Laurens van der Post recalled, ‘many post-war occasions when he [Jung] spoke with increasing urgency of the necessity for us all to understand that the Russian problem in the external world could never be resolved without more disaster unless we first dealt with the Russia in ourselves.’[xiii] Through the Cold War and beyond, from South America to Vietnam and Iraq, the U.S. acted with just as much contempt for human rights and international law as the Soviet Union, or Russia. Even under Obama’s Presidency, drone strikes – extra-judicial assassinations – were a recurring projection of U.S. power.

The main difference between ‘East’ and ‘West’ has been, for the most part at least, domestic preservation of the Rule of Law, including freedom of expression, in the latter. This has permitted criticism on the fringes, if not in a mainstream media often beholden to corporate interests.

The expansion of NATO into Eastern Europe in the 1990s stoked Russian fears of encirclement, bringing a desire for a strong, militaristic, leadership to protect the country from outside interference after the chaos of the Yeltsin years. More recently, EU leaders sought to absorb the Ukraine into the Western orbit. This is despite many parts of that country containing Russian-speakers with a nostalgia for the predictability of life under Pax Sovetica.

Ukraine’s fertile plains were the bread-basket of the Tsarist and Soviet Empires, making many Russians understandably apprehensive about a complete divorce. Moreover, Russia’s military planners see these flat lands as military indefensible, and her ‘natural’ frontier as extending to the Black Sea, Carpathian mountains, and flood plain of the Vistula.

Squeezed in the middle, Ukrainians labour under kleptocratic and tyrannical rulers serving interests in both East and West. But many Western commentators have failed to acknowledge the machinations of the latter, while magnifying the role of the former amidst a twenty-four hour news cycle that offers little time for dispassionate reflection.

Trump-Russia

The arrival of Donald Trump at the U.S. Presidential helm may prove to be one of the worst disasters to afflict the world’s environment. He is the quintessence of a loud-mouthed American who knows nothing of the world, or even his own country, while irrationally believing in his powers of divination, and capacity ‘to get the deal done’.

For many commentators the success of his malignant buffoonery requires an external explanation, drawing attention from the disgust that many ordinary Americans justifiably felt towards a Washington capital seething with lobbyists, spooks and over-paid bureaucrats. Enter Vladimir Putin in the Karla role – himself an ex-KGB agent – manipulating not only Trump, who is supposed to have been captured in flagrante delicto romping with Eurasian hussies, but also the American people who – according to this narrative – have been stupefied by Russian trolls: “Russia’s strengths” according to Timothy Snyder.

Whatever about the veracity of any claims of Russian collusion, or the idea that U.S. intelligence community could so easily be outflanked, psychologically we appear to be obscuring the ‘Russia in ourselves’. The United States is an increasingly dysfunctional and unequal society. Aside from the dismantling of Medicare, the appeal of Trump to blue collar American is not entirely irrational. He promised to protect indigenous U.S. industry, and ‘drain the swamp’ of a widely despised capital. ‘Lying’ Hilary Clinton was correctly seen as an establishment figure who would do nothing to alleviate the continuing decline of working class America, bedevilled by obesity and drug addiction, while real wages have stagnated for decades.[xiv]

No doubt Putin sought a friendly regime in the White House, but pundits habitually exaggerate the Russian leader’s influence, just as many journalists blithely accepted the nonsense about Saddam Hussein constituting a threat to global peace. The accumulated myth of the sly and aggressive Russian has been given a new lease of life.

A Colossus of American Journalism

Seymour Hersh is a colossus of American journalism, who has interrogated the structures of power internally and externally since the 1960s, invariably setting the record straight. His real breakthrough was exposing the My Lai massacre during the Vietnam War; he went on to reveal chemical and biological weapons programmes in the late 1960s; internal repression of anti-War groups by the CIA; mafia intrigues; the foreign policy dirty tricks of Nixon and Kissinger; the hypocrisy of JFK’s Camelot, U.S. links to Saddam Hussein’s weapons programmes in the 1980s; and the horror of Abu Ghraib. Without his tireless work we would know a great deal less about Uncle Sam’s unseemly side.

It is reassuring that neither Hersh, nor his family, were harmed over the course of an ongoing award-winning career, contributing especially to the New York Times and The New Yorker. He records just one death threat in that time, from a prominent mafia fixer in the 1970s.[xv] Among the American establishment there were, and still are, progressive forces resisting foreign misadventures and barbarities, such as using a sack full of fire ants to extract information from an internee, as occurred during the so-called War on Terror.[xvi]

Seymour, ‘Si’, Hersh, photographed in 2004.

Fascinatingly, however, in his Reporter: A Memoir, Hersh bemoans the unwillingness of editors in the New York Times to support investigations into corporate America in the late 1970s, which frustrated him at one point to such an extent that he hurled his typewriter out the office window – the following day the window was replaced and nothing more was said of the incident.

Hersh recalls:

Writing about corporate America had sapped my energy, disappointed the editors, and unnerved me. There would be no check on corporate America, I feared: Greed had won … the courage the Times had shown in confronting the wrath of a president and an Attorney General in the crisis over the Pentagon Papers in 1971 was nowhere to be seen when confronted by a gaggle of corporate conmen.[xvii]

The point about freedom of expression in the English-speaking world is that mainstream media only generally conduct investigation into threats to political and economic stability. The Watergate investigation was permitted, as this was an illegal attack on half of the U.S. political establishment; also, a significant proportion of America’s elite began to viewed the Vietnam War as unwinnable after the Tet Offensive in 1968, permitting critical articles form Hersh and others. But investigating white collar crime can be to the detriment of advertisers, and therefore altogether more difficult to pursue.

Holding his nerve

Hersh delivers a withering assessment on further media decline in the Internet era:

We are sodden with fake news, hyped-up and incomplete information, and false assertions delivered non-stop by our daily newspapers, our televisions, our online news agencies, our social media, and our President.[xviii]

The problems are by no means restricted to the purveyors of fake news, external or otherwise:

The mainstream newspapers, magazines, and television networks will continue to lay off reporters, reduce staff, and squeeze the funds available for good reporting, and especially for investigative reporting, with its high costs, unpredictable results and its capacity for angering readers and attracting expensive law suits.[xix]

He concludes: ‘it’s very painful for me to think I might not have accomplished what I did if I were at work in the chaotic and unstructured journalism world of today.’[xx]

As an old school reporter that pursued stories as doggedly as his body permitted, Hersh now considers himself an odd-man-out, and has found his recent reporting falling foul of editorial disfavour, even in supposedly progressive outlets such as The New Yorker, and The London Review of Books. Thus, while investigating the assassination of Osama bin Laden, David Remnick, the editor of The New Yorker, who had close ties to the Obama administration, complained about his use of the ‘same old tired source’, much to the grizzled Hersh’s bemusement.

Perhaps more surprisingly, The London Review of Books delayed publication of another article he wrote challenging ‘the widespread perception that Bashar Assad had used a nerve agent two months earlier against his own people … The article, which was taken by many as an ad hoc defence of the hated Assad and the Russians who supported him, and not the truth as I found it’,[xxi] worried the editor. As a result Hersh took the story to Der Spiegel.

Corroboration arrived in early 2018 when Defense Secretary James Mattis diverted from the previous narrative about the chemical attack, saying: ‘We do not have evidence of it’. Mattis can hardly be described as a Putin supporter, considering he resigned over Trump’s abrupt announcement that he would pull U.S. troops out of Syria – which presumably gives a free hand to the Russians. An investigator as formidable as Hersh generally has his ducks in a row.

Russia Today

In many respects, the state news agency Russia Today acts as a mouthpiece for Putin’s government. At times it does purvey what appears to be fake news, casting a fog of uncertainty over the reliability of everything it publishes. But to suggest mainstream media in the West is not also serving vested interests would be naïve, and fails to recognise that what is delivered as news is a product of editorial decisions: facts do represent opinions, contrary to one banal advertising slogan of the Irish paper of record.

Any online publisher, even a reputable state broadcaster such as the BBC, measures success in ‘clicks’, albeit the bait must be sophisticated if it is to ensnare the educated reader. A bare-chested, unapologetically homophobic Vladimir Putin performs the role of pantomime Russian villain with aplomb. Even The Guardian is not immune from dangling half-baked investigations before its consumers.[xxii] Seymour Hersh, notwithstanding his contempt for the U.S. President, stated in 2017: ‘Trump’s not wrong to think they all fucking lie about him.’[xxiii] The Trump-Russia affair may prove to have more to do with inter-agency disputes – cops and robbers – than Russian machinations.

But the buffoon Trump must have been manipulated by the Eurasian spymaster, whose agencies have ingeniously transformed the Internet into a labyrinth of conspiracy theories and distracting nonsense, right under the noses of the CIA, FBI and NSA. This allows us to avoid assessing the ‘Russian in ourselves’, and acknowledging the pathologies of Western societies, from social media addiction to ever-widening inequalities, and ecocide.

With mainstream media failing to pursue vested interests, the greed that Seymour Hersh points to may have won, for the time being at least. It is simpler to blame a straw Russian bear, rather than examining the serious failings in our own societies.

We rely on contributions to keep Cassandra Voices going.

[i] See Peter Hopkirk’s canonical account: The Great Game: On Secret Service in High Asia, New York, Kodansha, 1992.

[ii] Ben MacIntyre, The Spy and the Traitor, London, Penguin, 2018, p.46

[iii] Ibid, p.26

[iv] Ibid, p.130

[v] Lee Fang and Zaid Jilani ‘DEFENSE CONTRACTORS CITE “BENEFITS” OF ESCALATING CONFLICTS IN THE MIDDLE EAST’, The Intercept, December 4 2015, https://theintercept.com/2015/12/04/defense-contractors-cite-benefits-of-escalating-conflicts-in-the-middle-east/ accessed 15/1/19.

[vi] Jonathan Turley, ‘Big money behind war: the military-industrial complex’ Al-Jazeera, January 11th, 2014, https://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/opinion/2014/01/big-money-behind-war-military-industrial-complex-20141473026736533.html, accessed 14/1/19.

[vii] Seymour M. Hersh, Reporter: A Memoir, New York, Random House, 2018, p.300.

[viii] Alexander Solzhenitsyn, The Gulag Archipelago, New York, Perennial Classics, 1974, p. 173.

[ix] It is believed that most of these payments were used by Foot in order to keep afloat the left wing newspaper, Tribune, he edited. When the cabinet secretary, the politically neutral Sir Robert Armstrong, was presented with this incendiary information he elected not to inform the Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, assuming, correctly, that Foot would lose the forthcoming election in 1983. MacIntyre, 2018, p.142

[x] Ibid, p.200

[xi] History News Network, ‘Yale’s Timothy Snyder says Russia pioneered “fake news”’, May 4th, 2018, https://historynewsnetwork.org/article/168751, accessed 14/1/19.

[xii] Marlene Laruelle, ‘Is Russia Really “Fascist”? A Comment on Timothy Snyder’, Ponars Eurasia, 9/2008, http://www.ponarseurasia.org/memo/russia-really-fascist-reply-timothy-snyder, accessed 15/1/19.

[xiii] Laurens van der Post, Jung and the Story of Our Time, London, Verso, 1976, p.22.

[xiv] Drew Desilver, ‘For most U.S. workers, real wages have barely budged in decades’, Pew Research Centre, 7th of August, 2018. http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/08/07/for-most-us-workers-real-wages-have-barely-budged-for-decades/, accessed 14/1/19.

[xv] Hersh, 2018, p.234.

[xvi] Ibid, p.318.

[xvii] Ibid, p.247.

[xviii] Ibid, p.3.

[xix] Ibid, p.4.

[xx] Ibid, p.5.

[xxi] Ibid, p.330.

[xxii] Erin Durkin, ‘Trump: report FBI investigated him as possible Russian agent is ‘insulting’’ The Guardian, January 13th, 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2019/jan/13/donald-trump-russia-new-york-times-washington-post-fbi-putin, accessed 14/1/19.

[xxiii] ‘Tyler Durden’, ‘Seymour Hersh: “RussiaGate Is A CIA-Planted Lie, Revenge Against Trump”’, ZeroHedge, 8th of February, 2018. https://www.zerohedge.com/news/2017-08-02/seymour-hersh-2018, %E2%80%98russiagate%E2%80%99-cia-planted-lie-revenge-against-trump, accesseed 14/1/19.