Disregarding chronological order, this is the tenth episode of A Monk Manqué, Bob Quinn’s unpublished (unpublishable?) memoir A Monk Manqué, following

A Monk Manqué – Thaura Mornton

Culchies – An Excerpt from A Monk Manqué

Last Days in RTÉ – ‘I have come to kill you’

The Conman and Correspondence with Kurt Vonnegut

Old Man Talk – ‘I used to ride young wans in here’

Job Interviews

Trudie Fursey, a 7th century Irish saint, was born on Lough Corrib in Co. Galway. He had a church named after him and like many others expanded his missionary operations to Britain and the Continent, dying in 652 in a village called Mezzerolles which was renamed Forsheim and eventually became Pforzheim.

Looking across the Lough towards Inishlannaun/Inis Fhlannain from the churchyard of Our Lady of the Valley Church. Image: Trish Steel.

We Irish were always wanderers. Ending up as a teacher in Fursey’s adoptive town brought my tally of successive occupations to seventeen.

The advertisement in The Guardian resulted in an interview in Manchester University, where a laconic man showed no interest in my previous teaching experience. This was fortunate because I had none.

It seemed sufficient that I could distinguish between standard English and say, Urdu. It was a bonus to actually speak one of the King’s dialects – even without a Home Counties accent. The fact that my contemporary, Ronnie Drew, was also teaching Dublinese in Spain gave me confidence, at least enough to satisfy my interrogator.

I travelled back to Dublin to collect a couple of books and inform my parents. They had meantime taken note, on my behalf, of a quite different job opportunity.

I had time to fit in an interview with some men who were recruiting for a brand new Irish television service. I greatly enjoyed the interview, cared little for the result and assured them that with people of their good humour in charge, the service was sure to be a success. Promptly dismissing the matter from my mind I headed for the promised land, Germany.

Berlitz teaching techniques

Happily en route on the long train and boat journey and still daydreaming, I fell asleep, and did not awaken until the train stopped in Stuttgart, many miles beyond my destination. I had to wait on a cold platform until sheepishly boarding the next train back to Pforzheim. The unsmiling head teacher, the Frau Oberst who met me, was not impressed.

Pforzheim: View from Horse Bridge (Rossbruecke) along the Enz river.

I was given a month of learning Berlitz teaching techniques. My companion on the introductory course was also Irish. Her name was Colleen and she had just graduated as Miss Elegance, Trinity College in that same year, 1961.

Ours was a short and innocent interlude (a repressed Irish background ensured that). The reason Colleen and I were accepted for training was the sudden erection of The Wall. It had caused many expatriate English teachers to scurry back to Blighty.

A Third World War seemed possible. Being Irish, and innocent of world politics, Colleen and I had no bone to pick with the East Germans nor with the real villains, the Russians.

Our xenophobia was confined to the traditional Anglo-Saxon foe and sprang from a more ancient quarrel than that of the Cold War. Although she and I were doused in competing versions of Christianity, we shared the vague bond of Irish neutrality, such as it was.

We wandered contentedly by the river Enz, footloose because we were unshackled from the tight reins of culture and family, free to discuss anything we liked. Alas, once we had completed our short training course in Karlsruhe and were considered to be qualified Berlitz teachers, our fraternising was judged to be pedagogically unsound and she was retained in Karlsruhe while I was stuck in Pforzheim. Once we were separated I never saw Colleen again, one of the themes of my life.

Herr Dinkelbaum

That weekend I spent my entire week’s food allowance in the Goldene Adler pub and was consequently reduced to a diet of a single apple over three days. Hunger encouraged the hallucination that my life was over and food superfluous.

What was needed was an anaesthetic. The Goldene Adler supplied this in litres. Countless other hostelries have since been equally generous to me. I also came across Heinrich Boll’s ‘Irish Journal’ and its penetrating picture of 1950s Ireland made me homesick.

The interval of gloom was relieved by the arrival of a new student in my classroom. Her name was Trudie and she helped me forget. To relieve the earnestness of the classes I bought a yellow hand puppet which I called Herr Dinkelbaum and introduced him as a proxy teacher. I like to think Wittgenstein gave me the idea: think for yourself and trust your instincts. They’ll often get you into trouble but you’ll have a lot more fun.

Herr Dinkelbaum lightened the Teutonic gloom. One evening a student brought in a case of Coca Cola and a bottle of Vodka and the lesson became even more raucous.

But my Berlitz training course had omitted the vital detail that there would be a concealed microphone in each classroom. Despite my defence that to educate you must first entertain – which is an impeccable formula for television – my supervisor, the same Frau Oberst was unconvinced.

The subsequent rap on the knuckles – a deduction from my paltry pay – was, I felt, unduly harsh and I protested. Making a vague reference to Gestapo surveillance practices was also not a good idea. Only the scarcity of English teachers saved my bacon.

lovers’ corner

Trudy had a Botticelli shape, thoroughbred ankles, had lost her father in the war and clearly needed a father figure. Six years her senior, I seemed to fit the bill.

We spent many happy hours in the Goldene Adler pub/restaurant where in lovers’ corner there was a sign in German saying, ‘Here it is permitted to tell lies’.

After a couple of delightful months, however, a letter from Ireland reminded me of that long forgotten interview in Dublin. The new TV service was offering me a job, to start immediately.

In no hurry, I wrote back saying my contract would not allow me to leave yet. I lingered for a month in Pforzheim to enjoy Trudie, consider my options and save up the train fare. Would I stay in Pforzheim with Trudie and become a penniless would-be writer or would I please my parents by taking this job?

For once I decided they deserved a break, bade Trudie a tearful farewell and returned home. A month later I got an even more tearful letter claiming that she was pregnant and I must return, otherwise she would set her GI brother-in-law on me.

I ignored the letter and dived into the exciting world of television. But the past was always on my mind. Exactly thirty years after that parting I diverted from a filming expedition in Germany and paid a flying visit to Pforzheim.

With some basic research in the basement of the town hall I was given Trudie’s present married status, address and telephone number – a tribute to German thoroughness as well as their weakness for my elaborately romantic cover story.

Is that Robert?

I rang the number and in my half-remembered German said: ‘Is that Trudie Bopp?” She replied in German: ‘That was once my name.’ ‘Do you remember Herr Dinkelbaum?’ I asked. After a long silence, Trudie replied: ‘Is that Robert?’

Over coffee in the Goldene Adler which still existed (although the Berlitz school did not), I noticed she was still beautiful and spoke no English – a reflection on my teaching talents. She was clearly taking no chances with this blast from the past: she had arranged for her daughter to pick her up in one hour. They were going shopping for the girl’s imminent wedding.

Trudie remembered everything, even her threatening letter of three decades ago, to wit: if I did not return and face my responsibilities I would die. I asked her how old the daughter was now. Just twenty eight, she said. A quick exercise in mental arithmetic whetted my interest. Was it possible that I might have a half-German offspring?

There was not time to press the matter as the daughter duly arrived to whisk her mother away. I could hardly interrogate the girl or study her features for a resemblance. I felt a little disappointed, and not convinced either way.

The following morning, just before departing my hotel, curiosity overcame me. I rang the number again and asked Trudie to tell me the truth about her old letter. Now, decades later, she laughed and dismissed her white lie and the empty threat: ‘You must know what a young girl in love will say to keep her man.’

The realisation that she remembered our romance as clearly as myself was consolation. The Arab mantra ‘Man is the animal with the short memory’ is quite mistaken. I now remember ancient, significant things with more clarity than my breakfast this morning.

Now, where did I leave my coffee?

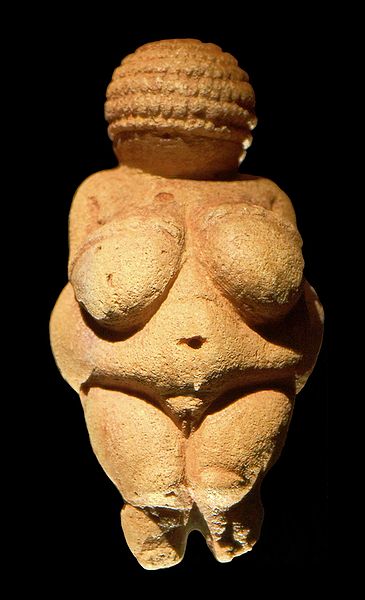

Feature Image is of the so-called Venus of Willendorf an an 11.1-centimetre-tall (4.4 in) figurine estimated to have been made c. 30,000 BCE.