PROLOGUE

‘The reverend Judge leaned over and addressed the defendant’

‘I have taken your spotless record into account.’

‘However…by the power vested in me I am obliged to sentence you to three score years and ten, maybe more, maybe less.’

‘You will serve this time in an open facility.’

‘Allowing for the normal remission for good behaviour as well as dungeon fire and sword, flood, war, illness, acts of God, built-in obsolescence and unforeseen accidents, you will enjoy a limited amount of personal freedom.’

‘As soon as you have interiorised the rules you will be left to your own devices.’

‘May the Lord have mercy on your soul.’

The newcomer beamed up at the man with the dog collar and gurgled happily.

‘Goochy goochy,’ smiled the Judge as he dribbled icy water from a chalice, down onto the infant’s head. The victim’s face contorted in shock at this first betrayal and its bawled protests echoed and re-echoed round the cathedral walls.

A MONK MANQUE

1/ Birthday

The recommended way to tiptoe through one’s eighties is to move as appropriately, delicately and prudently as possible.

But Oscar Wilde knew that ‘the tragedy of old age is not that one is old but that one is still young.’ Picasso agreed: ‘It takes a long time to grow young.’

Therefore, as the sun sets over your absent-minded yardarm there remains a sliver of light and life, a tincture of your compos (or, if you prefer, compost) mentis, implying the detritus of a long life. In the face of imminent extinction an extra birthday should be less a celebration than an act of defiance, a flinging of caution to the winds. What have you to lose? A dribble of sand in your hourglass? A narrowing shadow on your sundial, a mark on the wall of your cell, an acceptable stay of execution – anything but the conventional wisdom of decrepitude. Just face the fact that life has lived you, rather than the reverse.

On such an occasion avoid the liars who say: You’re Looking Great, Haven’t Changed a Bit. Translated, they are saying ‘you’re fucked.’

My exact contemporary, holocaust survivor Ben Barenholtz, who produced Coen brothers films and brought bread and vodka for he and I to ritually consume at the Galway Film Fleadh, told me he had an ex-friend, another liar who had said exactly the same thing to him every year for the previous twenty years.

The amusing thing about this compliment is that we ancients can’t help believing it. We skip and dance down the road – a pathetic, not to say gruesome image until we are forced to pause for breath. We then resemble the attitude of the nun in Elizabeth Jenning’s poem who was breathless with adoration. The cruel realisation is that we have simply run out of puff. In a Copenhagen pub not long ago that truth dawned on me in the company of two of my sons when I couldn’t resist dancing a hornpipe with a lovely young stranger. My legs needed a rickshaw taxi to get me back to the hotel while my fine sons continued their frolics until morning.

My actual state of health – fit as a trout in the opinion of doctors – is ironic. The pair of elderly Jehovah Witnesses who used call to my door, assuring me I could live to be one hundred and fifty if I accepted Jehovah, stopped visiting when I rejected their kind offer by quoting George Gershwin – loudly and in song

‘Oh, Methusaleh lived 900 years, but who calls that livin’ when no gal will give in to no man who’s 900 years…’

There’s the rub. As many of our faculties slither into the wings, the biological imperative insists on slyly hanging around, hoping like Lazarus for stray crumbs. When he was in his fifties actor Rod Steiger blamed his manic depression on those unreliable faculties. Myself, twenty five years younger than Steiger, had already intuited the tragic side of the human comedy.

But then I had the accumulated experience of three centuries – the 19tht, 20tth and 21stst – and five generations of my tribe. Three of my late grandparents – I never met the fourth – were born in the eighteen eighties and are as vivid and present to me in this room as their great-grandchildren when the latter noisily visit me. I can see all their faces, hear their voices, remember their gestures as well as I do those of my parents and my own children and grandchildren. Assuredly as their DNA, much of their experiences must lurk in my consciousness, co-exist in my eyes and ears – through which, after all, come my only perception of reality – and are as real to me as the screen before my eyes or the billion-celled stew of cells bubbling in the cauldron of our shared genes. This room is crowded and can be disturbing to one who always fled the proprietary demands of the tribe. To age is not to run out of ideas but to acquire a confusion of ghosts amidst the living.

They, young and old, are all here and not here, as simultaneously as Schroedinger’s cats. They so vividly exist, so demanding of my attention, that my direct and indirect human experience amounts to nearly one hundred and fifty years, just as the Jehovahs promised! So why am I not yet a wise and quiescent old man, nodding by the fire?

The reason is that I am male.

Females are blessed. They may suffer in our coming and going, but in time most of them lose interest in things libidinous – their body instructs them so – and they achieve a kind of equilibrium. Their vanity takes a different form – pride in their home, their children, an inside track to God and love of cats. They live longer than males by ceasing to chase windmills, by settling for less: security.

In my experience males were once listened to and females could safely be leered at. This was disastrous for both. The former became bores, the latter withered under the stares. Suddenly everything is reversed. Males are tentative and silent; females are garrulous.and assertive, to me an interesting evolutionary experiment. Mature, compliant females are an oxymoron but, as with unicorns, males still believe in the myth.

Such creatures must exist somewhere. Otherwise life is not worth living. Males are condemned to this poetic possibility ad infinitum or longer, a lifetime. Patsy Murphy diagnosed us as having ‘too much libido’. The libido is the killer, nature’s trick to keep the species going. A person can die of it.

Fifty years ago they conducted an experiment in the University of Berkeley (named after an Irishman, wouldn’t you know!) in California. They immersed a healthy male human specimen in a saline solution at body temperature. He floated as lightly as if he were in the Dead Sea. They doused the lights and plugged his ears. He was rendered sense-less, devoid of all stimulation. The outcome? Involuntary erection. I’ve read that it also happens to hanged men. Is that what Dylan Thomas, at nineteen, intuited when he wrote of the force that through the green fuse drives the flower? The French writer Michel Houellebeq is obsessed with the phenomenon, gaily mixing philosophy and social commentary and ending up with with sheer pornography. I would guess it has made him a Franc millionaire.

The fading of the faculties, the sense of impending annihilation, is the greatest imperative since Henry Kissinger boasted about the aphrodisiacal qualities of power. Hence the epithet: Dirty Old Man. Kurt Vonnegut jr. was more charitable when he wrote to me (always in block capitals on postcards): OLD MEN ARE OBSCENE AND ACCURATE.

Mr Vonnegut was my late and great penfriend who, like George Bernard Shaw conducted his correspondence by postcard. One of them was emblazoned: LIFE IS NO WAY TO TREAT AN ANIMAL.

When Pandora’s box is opened and releases all evils into the world the only thing left is Hope. During the conquest and annihilation of Berlin in 1945, all ages copulated desperately and publicly. Innocent courting games like ‘spin the bottle’ were discarded. Adolescent boys, knowing they would soon die defending their city sought a first and last joyful petit mort. For the girls it was to pre-empt their inevitable rape by a Russian soldier. War has that effect. The youngster were like rabbits transfixed in the headlights of tanks and they grew up faster than Margaret Mead’s famous teenagers in Samoa. They followed their first and last instinct: make love not war – but with somebody suitable. The few remaining active adults led by example. Threatened German cities were like chaotic brothels and all for free. I did not see the city of Munich until a dozen years after the sale was over. My timing is always haywire. Firebombed cities were inhabited by cripples, widows and orphans, many of the latter with high-boned Tatar faces, although starvation must have aggravated the effect. It is estimated that at the end of that last spot of European bother fifty percent of all surviving German females were raped. I read that in a book. I get all my real information from books. If the internet kills the printed book, my mind will go blank. I often quote Thomas Moore, the Irish balladeer: ‘All my books have been woman’s looks, and follie’s all they’ve taught me.’

Kurt Vonnegut happened to be in Dresden at the height of its firestorm so he was well qualified to have an opinion. He briefly summarised the calculated destruction of cities like Dresden, Hamburg, Berlin and Pforzheim with the pithy: ‘So It Goes’.

So far this seems to be all about love and sex and death? Pretty much. Next to food, what is more important than our driving forces, especially love, the engine room of the ship? We are all Darwinians now. Young optimists believe that love is an experience that is, has been or will be as neat, orderly, delightful and well conducted as ordained by someone called God, a part-time Hollywood producer. I remind ye who keep this faith (while all others are losing theirs) that ye are not paying attention. The bottle does not spin forever. A love affair is a mini-life: it begins in joy and ends in despair. Roll on the next one. We are a cosmic ditty, accompanied by a honkytonk piano in a sleazy bar.

Socrates put it more gracefully: ‘much of what men do is a desperate attempt to immortalise themselves; sensible women take the more direct route of having children’. Socrates regarded founding a family as a terror management strategy. The only simple reaction I have to these ponderous considerations is to keep singing and dancing provided, in keeping with subtle requests, that I do so in the privacy of my own kitchen.

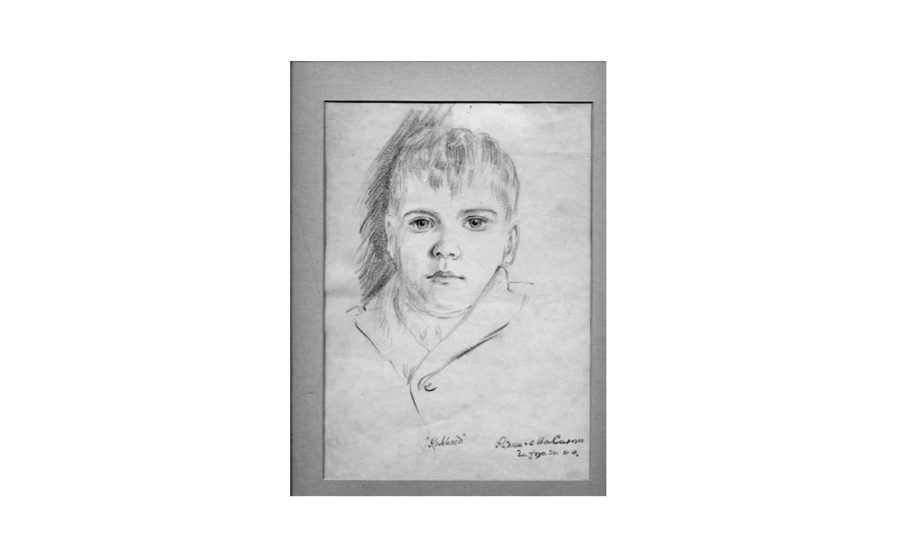

The truth of that great platitude, ‘yourelookingreathaventchangedabit’ is simply this: you are decommissioned. Writer Joe MacAnthony has described our generation as tourists in the departure lounge. We are in our anecdotage. Who would have thought that ‘Riobárd’, the child in the frontispiece to these words would survive so long?

How can I be the same person as that innocent four-year-old pencilled in my teetol father’s 1940 portrait?

Riobárd, as the child was named, must have had some intimation of what was ahead of him. How else could innocence survive the tripwires of life? Noam Chomsky said that there is an inbuilt matrix for complex language in a baby. Is there also an inbuilt preparedness for the hard truths of life?

It is a fact that my Uncle Jim Toner– who had run away from his home in Dublin to join the British Army and survive the slaughter of WWI – long afterwards described me, the child in the portrait, thus: ‘He may be alright but he has the head of a bloody rogue.’

I overheard that remark and worried about it, but nobody reassured me. Maybe Uncle Jim, a teenager in the Royal Army Medical Corps who had collected body parts of youngsters on the killing fields of Picardy – where the roses bloomed – was reminded of something unbearable in that innocent portrait?

Back in Dublin from his war service, Uncle Jim married what was known as ‘a servant girl’, begat no children of his own, endured public resentment at his fighting for the Old Enemy and sometime in the nineteen fifties decided to dull his pain with the aid of a gas oven. Post-traumatic stress syndrome was not then recognised. I have looked him up in the British Military Archives. He was awarded the DCM, abbreviation for Distinguished Conduct Medal, meaning he was immature enough to do something foolhardy in the midst of carnage.

Conferment of the D.C.M. gallantry award was announced in the London Gazette (1920) and accompanied by a citation.

Award Details: 61586 Pte. J. Toner. During the period 17th September to 11th November, 1918, while acting as a bearer, particularly at the capture of Bohain. There being a congestion of wounded, he repeatedly led forward squads of bearers over very difficult country during the night and greatly assisted in the evacuation of them

This had never been revealed to us children by our nationalist father although my mother, who concealed guns under her dress when céilís were raided during the War of Independence, often said ‘We were better off under the British.’

There were other military associations. When the British army abandoned our sacred soil in 1922, my mother’s sister Kathleen ran away with a British Tommy who, like her own father, my grandfather, reared pigs at their home in Berkshire. Their son Sydney, my uncle, became a teenage frogman in WWII and my hero. Years later I enticed Sydney’s daughter Kathy to elope with me to Ireland where we were known for a brief interlude as ‘kissin cousins’. Kathy later married a Red Devil, one of those RAF types who put on daring aerial displays. Admitting these connections makes me wonder if I am not an honorary member of that suspect class, a West Brit or Shoneen.

For a start, I was born in the Pale. My childhood radio listening consisted mainly of the BBC Home Service because Radio Éireann was broadcast for only a few hours per day. My first language was English, albeit in a dialect light years from the received pronunciation of the Home Counties BBC accent. My early reading was what we called the comic cuts: The Rover, Hotspur, Eagle, all published in England. My favourite authors were Robert Louis Stevenson, Arthur Conan Doyle, G.A. Henty, Agatha Christie, P.G. Wodehouse, John Wyndham, Leslie Charteris and so forth. Even the Irish language detective story writer Reics Carlo, who was obligatory reading in school, turned out to be English.

Among our official heroes, Pádraic Pearse was half-English, James Connolly was half-Scottish and James Larkin was a Liverpudlian. No wonder I am ambivalent about nationalism, both Irish and English. The last night of the Proms in the Albert Hall with its sea of Hooray Henrys roaring out ‘Land of Hope and Glory’ fills me with dismay and not a little envy. Filming American children reciting their oath of allegiance with hands on hearts every morning in school amazed me. Nationalism has become a dirty word in Ireland. How do the English and the Americans get away with their jingoism?

Perhaps because they are, respectively, past and present empires and Ireland’s only imperial achievements were spiritual and vanished into the ether.

As very soon must I.

This started off as a note on my birthday but could end up as a memoir, the grandiloquent lie. Every act of memory is an act of imagination, As all lives end in failure, my guess is that an honest memoir would produce in the reader a depression as deep as Killary Harbour.

Therefore this must, de facto, be another fictional memoir, a scrapbook, an anecdotal antidote to a life. Fortunately I am a magpie and keep the evidence: love letters, photos, notes, theatre programmes, membership cards, birth, marriage and death certificates, diaries, expired passports, manuscripts, film scripts, and so on and so forth. How I have kept them together after a peripatetic life is a wonder, but such memorabilia may keep me relatively, at least chronologically honest. They may raise an occasional giggle or even a sharp intake of breath in the wrong places.

I am past caring, one of the few benefits of ageing.

Bob Quinn is an Irish filmmaker, writer and photographer. His documentary work includes Atlantean, a series of four documentaries about the origins of the Irish people.

Did you know that Cassandra Voices has just published a print annual containing our best articles, stories, poems and photography from 2018? It’s a big book! To find out where you can purchase it, or order it, email [email protected]