Patrick Freyne’s satirical 2020 Irish Times article ‘It is now late-period Dermot Bannon. He is on the verge of losing it’ was an unusually humorous appraisal of the kitsch that state broadcaster RTÉ tends to dollop out.

In his novel The Unbearable Lightness of Being Czech author Milan Kundera explains that kitsch is an aesthetic ideal ‘in which shit is denied and everyone acts as though it did not exist’. This he argues, ‘is the aesthetic ideal of all politicians and all political parties and movements.’ The Montrose cultural bubble has long served a crucial political purpose: denying shit while everyone acts as though it does not exist.

Through no fault of his own, the feel good factor of Dermot Bannon’s show obscures the suffering associated with an enduring and arguably preventable housing crisis, and also, more broadly, provides an insight into how the Irish overreaction to Covid-19 occurred; which has done incalculable damage to the lives of children especially.

It seems that our best, and perhaps only, response in Ireland to these traumas is comedy, but this has clear pitfalls.

Image (c) Daniele Idini

“fronted by classical pillars”

Patrick Freyne reveals:

Dermot Bannon is my muse. I would write about him in every column if I could (God knows I try). If I were the arts editor I would make the arts pages of this paper entirely Dermot Bannon-themed. If I were taoiseach, I would declare a Dermot Bannon day …

He observes that

On every episode of Room to Improve, Dermot Bannon goes into battle with the plain people of Ireland in the cause of justice and light. Mainly light, to be honest. In his philosophy, there’s nothing that can’t be fixed by turning a wall into a window. He’d build all of his houses from windows if he could. The man is a martyr to big windows.

Explaining that Bannon:

is creating a metaphorical window into the heart of the Irish people, who are for the most part entirely unco-operative, ungrateful and obsessed with dark holes fronted by classical pillars and filled with Ikea furniture …

He also marvels at how:

Ireland is the only country with a celebrity quantity surveyor. Patricia has no time for any of Dermot’s nonsense, which is why we like her. He wants to double the size of his new house for just €350,000. The nation scoffs at this even before Patricia has a chance to say: “Not a hope.” In fact, we all say it along with her, panto style.

As one of the jesters permitted to ply his trade in the national media, Freyne exposes RTÉ’s consistent denial of shitness – which perhaps accounts for a prevalent uncooperativeness, ingratitude and obsession with dark holes “fronted by classical pillars.”

Much of the Irish landscape bears testament to the tragedy of the commons. It is a sad reality that most of what has been built since independence is inferior to what came before it.

Moreover, a programme such as Room To Improve, and it’s not the only one in this genre, is devoted to the improvement of private dwellings in the possession of a shrinking middle class still transfixed by the ups and downs of the Irish property market. It is instructive that according to the website www.daft.ie at the start of May, 2022 there are just over one thousand properties available to rent in all of Ireland at a point when the Irish government has just committed to welcoming tens of thousands of refugees from Ukraine. Is it any wonder so many people are disinclined to have children.

In essence Room to Improve translates into: how can someone increase the market value of their property. The lurking presence of the celebrity quantity surveyor ensures that any project is seen in terms of adding financial value to the holding.

It is particularly tone deaf as we reach another high-water mark in an ongoing housing crisis. Missing on RTÉ is serious engagement with the corruption of a planning process, which lies behind enduring inequalities and sprawl, or the financial structures that embed generational inequalities, and permit a creeping dominance of transnational capitalism.

It is not that housing dysfunction is denied on RTÉ – that we are lied to as such – it is that the issues are almost completely ignored amidst the day-to-day mixture of light entertainment and vox pop nonsense that are their mainstays. Room to Improve is a form of kitsch because it denies the shitstorm going on in the society around it.

And like the rest of their programming, it appears to rely to an ordinate extent on advertising from a motor car industry that allows for the trail of bungalows that blight our landscapes. After all, living in one of the detached houses that Bannon mostly works on would be very difficult without a motor car.

It also appears that RTÉ’s longstanding tendency to bury shitness – which is also evident in legacy print media – led to the catastrophic handling of Covid-19 in Ireland.

With Irish media placing unprecedented focus on climate change during #COP26 we recall an unhealthy dependence on advertising revenue from the car industry that appears to influence transport coverage in particular.https://t.co/wXx0LOgPVB@think_or_swim @WilliamsJon @ian_lumley

— CassandraVoices (@VoicesCassandra) November 1, 2021

Ongoing Kitsch

It will be many years before we come to terms with what happened during Covid-19 around the world, and confront the traumas, especially to children, of living through lockdowns. It is instructive that despite having the youngest population in the EU, Irish children were subjected to among the longest school closures in the world. Simply blaming teaching unions ignores how teachers were subjected to relentless fear messaging that made them reluctant to do their jobs, despite international data from early on showing that their concerns were generally misguided.

Yet for RTÉ ‘The deadly virus’ of COVID-19 seemed to arrive as a godsend – and an advertising windfall, or so-called Covid bounce. A slavish devotion allowed the channel to almost completely ignore all other difficult news for the best part of a year-and-a-half. The daily totals of cases and deaths, uncritically conveyed, became the staple of every radio and television news bulletin and headline on their website.

Then, almost overnight, the issue vanished from sight, without any kind of meaningful post-mortem or reflection on the damage inflicted on the patchwork of communities that make up our society.

It gives way to relentless coverage of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine – thick on spectacle and almost devoid of critical analysis. Images of wasted buildings now bury discussion of other stories.

A lack of intellectual rigour – albeit their Brainstorm section is a notable exception – that is essential to RTE’s kitsch reaches right to the top it would appear. Thus, RTE’s head of news Jon Williams claims in article ‘For the first time in Europe since the end of World War Two, one country had been invaded by another.’ The mind boggles.

Comedy appears to be the only response available; it’s just that the consequences are quite serious. Simply because political protestors aren’t subjected to imprisonment or torture as under other regimes doesn’t mean that the Irish state isn’t failing its people, and that the state broadcaster isn’t complicit for failing to interrogate our inadequacies that surely begins with a deficient education system.

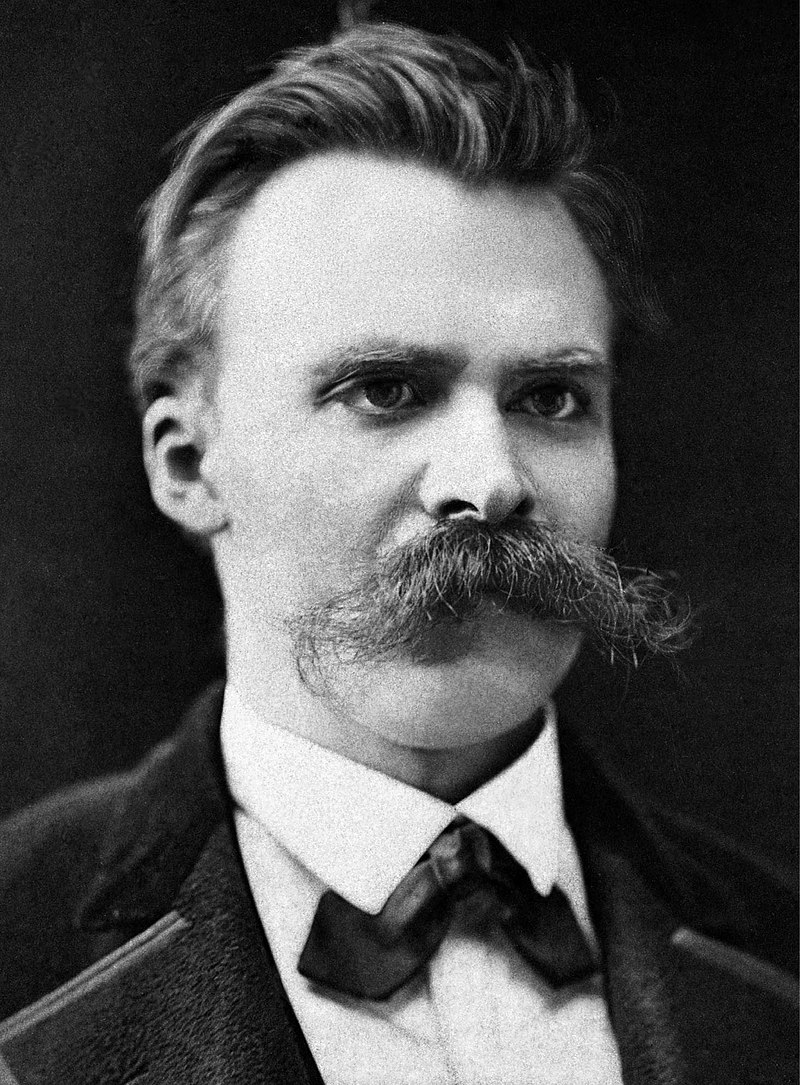

Nietzsche

In Laughter All Evil is Compacted

Freyne is one of a number of comedic writers and performers – Oliver Callan is another working for RTÉ itself – operating in legacy media who are permitted ‘to take the piss’ out of our national obsessions. Comedy has its advantages but arrives with a health warning.

Theodore Zeldin traces its historical trajectory: ‘since truth cannot be easily swallowed whole or raw, jesters were usually also poets, magicians or singers, able to convey unpalatable insights in an epigram, a witty story or a song.’

But this routinely slips into cynicism, as comedy can reinforce conformity ‘by being its safety valve.’ Zeldin points out that carnivals, such as the medieval festival of fools: ‘have throughout history made fun of authority, and turned hierarchy upside down,’ but ‘did so only for a few days.’ In a sense, comedy normalises the damaging excesses of a culture by turning it into a humorous spectacle.

Jokes can be truly sick, as the history of totalitarianism demonstrates. Jonathan Glover notes that ‘In the death camps the Nazis turned the cold joke into an art form, with increasingly imaginative embellishment on the themes of cruelty and humiliation.’

Friedrich Nietzsche provides a psychological insight into how this occurs when claiming that ‘in laughter all evil is compacted, but pronounced holy and free by its own blissfulness.’ The gay release of laughter allows depraved participants to evade consideration of their actions. Thus, humour may confront tyranny, but it may also reinforce it.

A parade of tanks of the ČSLA in Prague on Victory Day, 9 May 1985.

Not Dangerous In Itself

In Kundera’s view political kitsch is not dangerous in itself. Indeed, most democratic politicians cultivate a clean-cut, artificial, image. The real danger lies in totalitarian kitsch such as that encountered by the character of Sabina in the aforementioned novel, who recalls the Communist parades of her youth.

These projected an idealised vision of the worker removed from the corruption, suspicion and cruelty that had by then infected her society. Indeed, it is recalled in Czechia that under Communism love for one’s family required some of form of theft in the course of one’s professional career.

Kundera contrasts totalitarian airbrushing with the plurality of voices that he believed still lay in Western democracies.

Those of us who live in a society where various political tendencies exist side by side and competing influences cancel or limit one another can manage more or less to escape the kitsch inquisition: the individual can preserve his individuality. The artist can create unusual works. But whenever a single political movement corners power, we find ourselves in the realm of totalitarian kitsch.

Prior to Covid-19 RTÉ’s kitsch could largely be avoided, but when the state followed the example of its European partners in imposing undifferentiated house arrest we entered the dangerous territory, as we were subjected to a form of mass formation.

Conspiracy theory: Ryan Tubridy and Dermot Bannon are the same person pic.twitter.com/BVUjyu9VwP

— ciara doyle (@ciawadoyle) April 2, 2018

Ireland Inc has returned to business as usual. Room to Improve carries on with an architect that looks suspiciously like Ryan Tubridy, as the housing crisis continues to the benefit of a few, and all we have are tears of laughter for consolation.