Last week Andrea Reynell met renowned Irish man-of-letters Ronan Sheehan in his Dublin home. They discussed his abiding passion for Latin poetry, the challenges and opportunities for young writers and what has inspired him to assemble a volume of translations of Cuban poetry from a range of Irish writers.

I was welcomed into a cosy sitting room with a green/blue sofa, a pale wooden table with chairs, while dozens of photographs and art works adorned the walls. The Libyan Sibyl and another painting reminiscent of the great Irish epic, An Táin Bó Cúailnge (The Cattle Raid of Cooley) caught my eye. A well-used fireplace lay to my left behind Ronan, as the open door to the back garden let in a cool breeze as we sat at the table.

A: How did you get your start in writing poetry?

R: I don’t really write in poetry. I write more prose which I started writing when I was at school and I got interested in literature then. I had two things published when I was sixteen one was a short story in The Irish Press which was a big thing in my day. And the other was a poem in a magazine called The Kilkenny Review, or something like that. But subsequently I learned to love poetry, but I don’t really write poetry. I can write translations which is a different thing.

A: I’d be the same myself. I prefer writing prose to poetry. I’ve been doing a few bits and pieces but don’t have anything published. But as long as I enjoy it really. How much do you reckon the Irish literary society has changed since you first started writing?

R: That’s a good question. I think It’s changed a lot. When I was in my teenage years the nineteen-sixties. I suspect you weren’t born then Andrea.

A: (laughs) No. Not even close.

R: For starters there was very little or no publishing houses in Ireland and when The Irish Press started to publish stories and poetry that was kind of revolutionary because the only other places were a couple of literary magazines that was all that was there. And consequently, to get something published was a big deal. And now there are a lot of publications and in some way that’s better, in the sense that there’s more chances for people to start off. In other ways I have reservations about it because I often get the sense that there’s too much going out. I hope that doesn’t sound mean spirited.

A: How important do you think the arts are today?

R: I think the arts are very important if you like but, for this reason that what you might call the world of culture. It’s really dominated by enormous interests, the high-tech companies like Google and also by Hollywood and big music companies so that the small country and the individuals are really cowed by the sheer power of those things. So, whenever the arts afford individual voices to be heard I think that’s very important for that reason. I mean I could name other reasons as well but that’s one cultural reason as to why I think the arts are very important.

A: What poets, or writers past or present would have an influence on your work?

R: Jorge Luis Borges

(There’s a photo of the late, famous Argentinian writer on top of the book case across from me) Do you know who he is?

Jorge Luis Borges (right).

A: Yes, I’ve read up on him.

R: Did you read it from my essay?

A: I did indeed, and it was very interesting.

R: Thanks a lot. Sorry I wasn’t looking to drag that out of you!

In school I studied Classics and I studied Latin and English when I went to UCD. While I really loved that engagement with books and so forth and as I got older I realised that there were some books and some writers and even some works that touch you. In a way that is not necessarily quite rational. You don’t look at all the points in Ulysses like you’re taught and say: “oh that’s a great book.”

But it’s different when something affects you right? So I hope this doesn’t sound pretentious but a writer whom I loved in Latin was Catullus who was a Latin poet and I did a project about Catullus some while ago. And another writer was Tacitus who was a historian so that’s one thing, don’t want to go on forever. Another person that I loved, as I wrote a book of short stories was Borges and it was a thrill for me to meet Borges. And if you read the essay that I did I think I’ll always remember. When I quoted to him something that he’d said about Tacitus. And he said, “Tacitus records the crucifixion but does not perceive it” and Borges just looked across and said “Did I write that? I don’t think I’m a very good writer you know, but maybe in the sixty years trying I’m entitled to the odd good line.”

A: That’s brilliant

R: Isn’t it?

A: That just really encapsulates who he was.

R: Yeah it does. It’s a very good position for a writer to be, you know. Not to be arrogant, not to be presumptuous that you’re great. In my case I’ve written a few things I think came out well, a lot of things that didn’t. But I’d much prefer to be in Borges’s camp and say well, I think one or two things came up, you see. So, you’re sort of at ease with yourself in that position, does that make sense?

A: It does indeed. And how much of an impact do you reckon he’s had on your future and current work?

R: He had an influence on some of the essays that I’ve done, and he has an influence on a book that I’m writing now, and I’ll tell you why. That while I say an influence, it’s something that I have in my ear or try to do well is, he has a terseness, a succinctness about his sentences that I love because they’re so resonant. And when you leave down a page that Borges has written you feel this resonance of meaning and possibility and a richness of language so it’s beautiful you know it’s lovely. That’s what writing is for and I would love to try and imitate that.

A: So, for the readers of this article, where did the idea for the book of poetry come from?

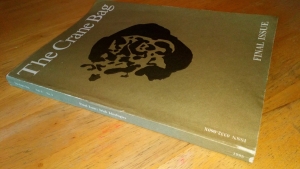

R: Many years ago I edited an issue of a magazine called The Crane Bag on Ireland and Latin America and for one reason or another I don’t think I was able to do anything Cuban in that issue. One of my favourite books is a Cuban book called The Kingdom Of This World by a writer called Alejo Carpentier which is about the slave revolt in Haiti in the 1790’s, then Santo Domingo. So when I was on the board of Poetry Ireland about twenty years ago, the possible of going to Cuba came up. So, I went and met people in the writers’ union including the president and we made an agreement that we would do a joint anthology of poetry together, that’s how it came about.

A: What would your favourite poem of the anthology be and why?

R: That’s a good question. It is a poem that translated by Trudy Hayes and it’s called, It’s a poem about. (He trails off here) How about I go get it? It’s very short, I’ll read it, it’ll be nice.

A: Yes, go ahead.

He walks out of the sitting room, which leaves me a chance to take in the abundance of things on the walls. A clock ticks away, a steady beat, as I wait for him to return. He soon reappears with a black book.

R: This is a proof copy of the book. If I may say a little bit about the book?

A: Yes, absolutely.

R: So, see what you make of this, this is called ‘Blessed are the Mean Spirited’ (Interpreted/translated from Spanish by Trudy Hayes)

Blessed are the unperturbed spirits

Not born of a poisoned womb

Or terrorised by a lurching ghost,

Or by their own raging seed,

Those erupting with a terrible sickness

Doomed to wander eternally a path in the wilderness that never

leads home.

Blessed are those not burning on a furnace of love,

The unmarked smiling ones,

The behatted archangels In fishnet tights,

The patters of bellies, the jellied ones, the loved ones, the

virtuous ones,

The pied pipers and their enchanted mice, the business tycoons

and the Superheroes,

The movers and shakers, the poised, collected, unshaken ones,

The fragile ones, the wise ones, the palatable ones, the smiling

and waving ones,

The truly fine ones and the truly sweet ones sweet to the core.

Blessed are the Innocent birds of paradise, the steaming cow

dung, the Implacable stones.

But MAKE WAY for the creatures of the Dream and the

Nightmare.

Make way for the lost, damned, grief-stricken souls wandering

a lonely path.

Madder and drunker than their ancestors. Scorched by love.

Trying to find a way home to the house of straw hats, for they

saved you.

A; Wow, that’s haunting and ominous but powerful

R: Isn’t it? I hate sounding like a professor, but one of the things I like is the kind of writing that makes a point, which communicates something. Lots of poetry doesn’t do that but that’s fine, there’s nothing wrong with that. I read that out at a street party during the summer and Trudy read it out somewhere and people responded to it. Do you know they thought that was good. Ok so that’s one thing. It either speaks for itself or it doesn’t. Another thing I’d like to say about this book. It’s about fifty Cuban poems and about fifty translations and without going into the entire history of the whole thing, it’s quite powerful if you bring it into a book, lots of different voices. Some of the people translating are really well-known poets who are lauded, others are people I brought in, they’re not poets at all. But they’re good, they’ve got something to say, they can use language, they’ve got some spirit. So that when you’re reading this you don’t know what to expect next, so the idea is to give a book a kind of potency like that.

A: I find that’s exactly what it does, so moving along to another question. I found there was a big difference in formality between some of the poems, so for example The Boy and the Moon with lines like:

The moon and the boy play

A little game between them;

They see each other without looking, they talk in fits of silence.

Versus in ‘Pineapple’ where we have a lot more of what you could call Irishisms.

Indulge me, pineapple.

Imagine if bould Fergus,

leppIng from Tara had given Glasgow a miss,

Ryanairing it instead to hotter shores.

I love that line.

So, What are your thoughts on the differences in this language?

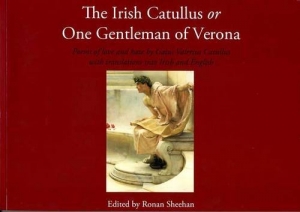

R: Ok can I be theoretical for a bit? This is going to sound academic or whatever. Ten years ago, I did a translation of the Latin poet Catullus called The Irish Catullus or One Gentleman of Verona. It was a protest against the closure of the Classics Department in Queens University. The phrase the Irish Catullus really derives from a translation of the Aeneid which is called the Irish Aeneid. What was called the Irish Aeneid was the first ever translation of the Aeneid into a vernacular language in the thirteenth century by a bard of Ireland. They translated it before anybody in Oxford or Cambridge or anything, ok? But the way he did the Aeneid was he really rewrote the whole thing right, like he reshaped it. (Ronan gives a laugh here)

A: As you do.

R: As you do. The whole point of this was so that the people of Sligo, and Mayo and Galway and that culture could receive it otherwise there was no point in doing it.

A: So, I guess you could say in ‘layman’s terms’ more or less.

R: Yes, exactly. In the culture that it was going into. So I invited the people, including Mia and the people who were translating the Catullus poems to do it in what I call the Irish Aeneid spirit. To reshape it, to put it into our context if they wanted to. There’s a hundred translations of Catullus. What’s the point in doing another in just the same way? So, people did that, and Mia did it brilliantly. There’s lot of sex in Catullus. Roman street sex poems and Mia translated them into Dublin sex poems and they’re brilliant, they really work. So here what she’s done is something similar and a different idea. She hasn’t just followed word for word the poem, she responded to it and she’s introduced her own language and that’s a perfectly legitimate thing to do.

A: So, what challenges did you face when translating poems from Spanish to English, do you think some things may have got lost in translation?

R: Yes, I think it’s a truism that something gets lost in translation but equally if nothing is translated everything gets lost. So I think Spanish in a way is deceptive in that you’d think that because the words are specific, that you can’t just use a dictionary and translate them, but you can. But the thing that’s not so easy to do is the rhythms of Spanish like they have noche que noche oscura (‘night what a dark night‘s’). It doesn’t sound the same in English so that’s in some of the poems. I have a little Spanish, and I can see there’s a whole atmosphere and world in those poems that doesn’t necessarily come out through translation, but something else does come out which makes it all worthwhile.

A: In the preface you say that fifty poems by Cuban poets born prior to 1959 were chosen and fifty poems by Irish poets born prior to 1922 were chosen. Is there a significance to these dates?

R; Yes, the reason is that there was the Cuban Revolution in 1959 and there was the Irish free state (that was established) in 1922 (and the Irish Civil War) so in a way the idea was to sidestep the issue of the revolution in both countries.

It’s an axiom of journalism that if it’s anti-Cuban it has to be true. Keith Bolander explores ongoing vilification of the Revolutionhttps://t.co/yWHqfkBFQS@broadsheet_ie @pyjamas_black @KevinHIpoet1967 @DLangwallner @NMcDevitt @looplinefilm #cuba #CubanDoctors #CubaSalvaVidas

— CassandraVoices (@VoicesCassandra) July 9, 2020

A: Again in the preface, it was written that fifty Spanish poems were swapped with the Irish side and fifty poems in English were swapped with the Cuban side. But in the end fifty Spanish poems were taken and were translated into English and given an Irish interpretation. Why did you decide to take this route rather than have Irish poets write their own poems?

R: That’s another good question too. Because this is the first encounter between the two countries at this level although there’s another interesting one which I’ll come to in a minute. So it’s better to sometimes manage something like this. There was a formality in a way that perhaps made this manageable whereas if you were to open it up in the way you had described it would be a different proposition.

A: What will your next writing or poetry project be?

The criminal court of justice, Dublin. Daniele Idini/Cassandra Voices

R: The next writing project I will be doing is to revise a book that I’ve been working on for a while which is called Green Street. Green Street is the name lawyers gave to the Special Criminal Court. Did you ever hear of Robert Emmett?

A: Yes

R: Did you ever hear of Sarah Curran, Robert Emmett’s fiancée? My cousin Margaret is a descendant and looks like her and that’s her up there in the green hat. (He points at a photo framed by the door). See, so she has to go to Green Street. What do you think of that? Anyway, so that’s what I’m going to be doing. So yes the most famous thing that ever happened in Green Street was the trial of Robert Emmett. And as I say Robert Emmett was in love with Sarah Curran, and I also did cases on Green Street and a few years later my brother and I did so in a way exploring that.

Sarah Curran playing the harp. Painted by William Beechey, c.1805.

A: Is there anything else that you’d like to comment on that you feel would be important for readers to know?

R: I think that I’m going to make a compliment to Cassandra Voices shall I do that?

A: If you like, can’t go wrong.

R: A really good thing that can happen in literary culture is to have small groups or magazines that are bringing out books or magazines and programmes that are independent. That’s really what I know in my experience of such things, that’s where real creativity resides.

After I stop recording, I get a closer look at the photo of Sarah Curran’s ancestor, the green hat is indeed striking, the face shapes are similar too. I thank Ronan for his time and step out into the warm sunlight to make my way home.

Feature Image: Daniele Idini (c)