The theme of ‘late art’ was recently explored by the art historian Carel Blotkamp in The End: Artists’ Late and Last Works (2019) focusing on the visual arts, but in an age nonspecific way.

Raphael’s ‘Transfiguration’ is central to the argument of the book. After Raphael’s death, the author notes his body was laid out beneath the painting in his studio. Vasari tells us that ‘the sight of his dead body and this living painting filled the soul of everyone looking on with grief.’

Raphael died aged just over thirty years of age. Picasso in a much later blasphemous parody had Raphael fucking. More on Picasso and indeed fucking later. This is an article about The Rolling Stones after all.

More representative of late art in literary terms is Thomas Mann’s Doctor Faustus 1947, which was written when he was nearly eighty years of age, and was his second to last work. The last being Felix Krull, both of which were discussed in a previous article for Cassandra Voices. In these works his style loosens and is fresher than his earlier work. I attribute this revitalisation to his hatred of fascism and fakery.

Both of these books were written in old age when the light was dimming, which is remarkable. Great art arrived against the odds, with physical and presumably mental powers failing. Like Michelangelo finishing off the frescoes in the Sistine Chapel with the Last Judgment or even more so the late sculptures.

Picasso approaching ninety, as the aforementioned book references, famously started working faster and faster, painting in a sketch-like figurative way: parodies, exhumations of the western tradition such as by Valazquez Los Meninas; in contextual or parodic form; painting as ideas with the clock against him. He famously said in this respect: ‘I have less and less time, and yet I have more and more to say.’

Well, what a drag it is getting old.

heatfield with Crows — oil on canvas 101×50 cm Auvers june 1890.

More commonly…

But Mann and Picasso are uncommon. More commonly, artists repeat earlier tropes or descend into sentimentality, commercial opportunism or simply kitsch as they age. The late works of Marc Chagall and Salvador Dalí fall into these categories. Opera Designs or endless recycled Kitsch is very evident in the Dali Museum in his hometown of Figures.

The phrase ‘late style’ is also relevant in this context and is, in fact, culled from Theodor Adorno’s 1937 essay on Beethoven. Adorno – and, more recently, Edward Said, whose own last book was on late style – both suggest in a distinct echo of Picassos observations that regularity, precision, and tidiness no longer matter when an artist is faced with death. The writing and painting become more scabrous, irreverent with a lightness and incompleteness but also harrowed.

One thinks above all else of the finest achievement in the history of art the late paintings of Rembrandt, where the artist is merciless in self-portrait particularly his damaged and aged eyes. Though the formal precision is, remarkably, retained. Another notable achievement is in the late work of Goya, his Black Paintings In particular. These are visceral images of human torture, misery, cannibalism, and insanity.

Adorno wrote that late art or style ‘does not resemble the kind one finds in fruit. They are not round, but furrowed, even ravaged.’

Many great artists of course die young and without the necessary anticipation of doom. Egon Schiele tragically dies in the ‘Spanish’ Flu Pandemic of 1919-1920. The Romantic poet Percy Bysshe Shelley drowned after a boat accident. So, the suddenness of a departure does not affect the art for good or ill.

Van Gogh hadn’t reached the age of forty, when he died, but the Wheatfield with Crows is one of his greatest works, the crows above providing a doom-laden portent. In contrast, the truly writer of The Great Gatsby F. Scott Fitzgerald was dead by forty-four having been dismissed as a burn out and a has been. He had felt compelled to hack for money, with the Pat Hobby stories. As he said there are no second acts in American life, although Donal Trump might disagree!

Some artists try and go out on top before retreating into isolation. Neither Harper Lee nor the reclusive J. D. Salinger published much after To Kill Mockingbird and The Catcher on the Rye.

We might tentatively say that generally the best work comes first or close to first, before decline sets in, often with coincident celebrity and accolades. The philosopher Jürgen Habermas once remarked that when they shower you with awards you know you are finished. Stressed vines make the best grapes by all accounts.

In this respect The Nobel Prize is often the kiss of death for creativity. Exceptions to that rule are of course Gabriel Marquez. He wrote as good if not a greater novel than One Hundred Years of Solitude (1967) after the award with Love in The Time of Cholera (1985). And then there is the incomparable Samuel Beckett, about whom more later.

Kurosawa the great Japanese film director was effectively persecuted by the Japanese state by being snubbed at awards ceremony. Suicide attempt followed, and but for the intervention of Steven Spielberg and George Lucas he would not have gone on to produce a work as incandescently brilliant as Ran, his Samurai adaption of King Lear, which is one of the greatest films of all time that he completed at nearly eighty years of age.

Better to burn out…

In Rock music there is a discernible trend in late art achievements. Leonard Cohen’s late albums include Old Ideas (2012), which includes the sublime song, or poem, ‘Going Home’. And Bob Dylan’s Rough and Rowdy Ways (2020) is a continuous flow of genius.

But both Dylan and Cohen were geniuses and not a bunch of blues-thieving, decadent often priapic monsters with a not undeserved reputation for all sorts of destruction of many of those around them.

Giving them their begrudging due, the shows are of course truly spectacular, as anyone who had the privilege of witnessing them in Glastonbury would attest.

The youthful audience, and some bemused older curiosities, largely came to bury Caeser, or Satan, but Sir Michael will not be buried easily and strode on stage in red barbed devilish gown, 28-inch waste and barnstormed, not least with sympathy for the devil.

Well yes, a tour band par excellence re-threading their hits from the 60’s and early 70’s and producing nothing of note in over two decades of self-enrichment. Bigger and Bigger Bangs of the same thing. Outrageously reliving their satanic rebelliousness. Funding Keith Richards drugs, albeit no longer indulged in apparently, and Mr Jagger’s endless libido – growing old as disgracefully as possible. Aged eighty, he is married to a woman almost fifty years younger. The lucky sod.

But the artistic community could rest assured there would be nothing further. No further trouble.

And then it landed ‘Angry’, the opening song of their recent studio album, Hackney Diamonds, a better starter I think than ‘Start Me Up’ and a better song than ‘Shattered’. Propulsive not 1970’s but 60’s revitalised and pared down. And Mr J. certainly sounds angry.

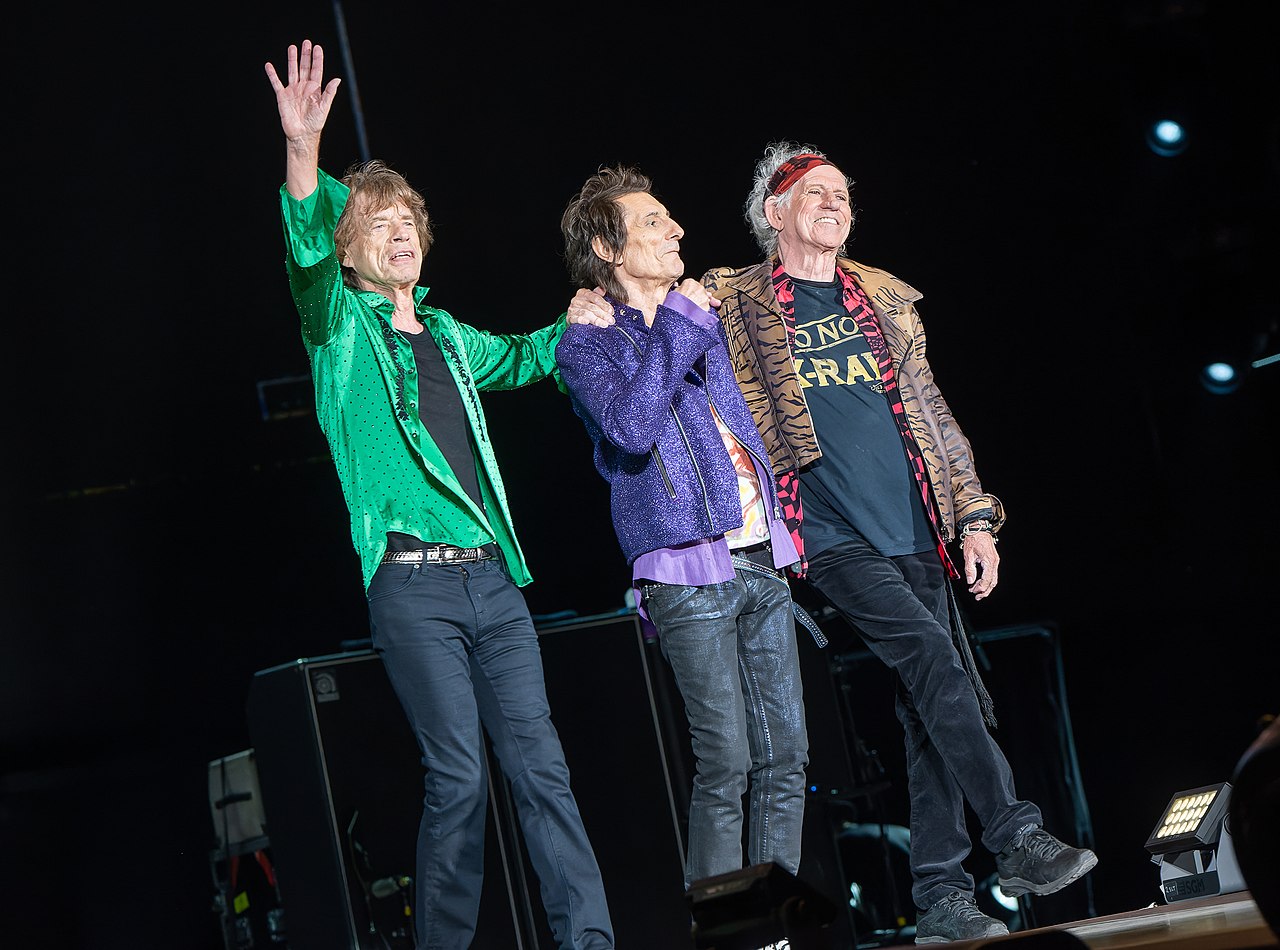

And so, three well preserved and ostensibly vigorous elderly gentlemen in casual costume get in touch with their north London roots and step fearlessly into Hackney, which of course they never hailed from, to introduce a brilliantly named album Hackney Diamonds, with a glorious smash and grab cover.

By any reckoning it ought to have been a re-thread or a bombastic disaster. But is simply a great rock n’ roll album. In my view the best pure rock and roll album since The Clash’s London Calling with a not to dissimilar mining of styles. It even includes a punk song with Paul McCartney on bass, who seems like he was having a ball with the band he had recently described as a Blues cover band. But what a cover band!

Burst of Blues Energy

The bursts of blues energy with at most one longueur is sustained through its forty-five propulsive minutes. The best comparison in terms of form and antecedents is Exile on Main Street, with the odd ballad mitigating the relentless noise. There are many great or near great songs. There is a rose in Hackney and not just Spanish Harlem. OMG.

In ‘Sweet Smells of Heaven’ Jagger sounds as great as in ‘You Can’t Always Get Want’ and ‘Angie’. In short it is one of the greatest ever Rolling Stones songs. Whether it ranks in the top ten is a matter for debate. In my view very close to the absolute pantheon Sympathy For the Devil.

Notably Keith Richard’s is in flying form. I wonder is arthritis loosening his playing style?

Geoff Dyer has recently published a book called The Last Days of Roger Federer and it is not intrinsically about Federer though he was also an artist but is about the dying light augmenting the enormity of the achievement.

Sir Michael who prompted the album to stir the wild beasts from their slumber now suggest they are three quarters way through a new album. A sense of enormous anticipation should now prevail. One hopes though it is not a set of discards and out takes.

Hackney Diamonds would be an incomparable way to put a full stop, but what if the next album is even better? After all, The Beatles in their pomp followed Revolver with Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, but that is now almost fifty years ago. Let us be clear Hackney Diamonds is the greatest stones album in forty years.

They have ascended the charts in Britain and the USA In a way unprecedented since their heyday. And methinks Mr Richards will not be thinking about the money. One senses that old rubber lips thinks the best is yet to come and will force them back into the studios. No pressure then lads.