Born in 1875, like many in his era Thomas Mann was initially a Great German Conservative, but by the outbreak of World War II he was making anti-Nazi speeches for the BBC.

Mann won the Nobel Prize in 1929 for his chronicles of German families in Buddenbrooks (1901), and for his bildungsroman The Magic Mountain (1924), along with a number of well received novellas and short stories. Among his later publications, the novella Death in Venice (1929) is a terrific book, expressing his repressed same-sex attraction; it is a worthy expression of a hyper-civilised, fin de siècle aesthetic intelligence. The film by Luchino Visconti with Dirk Bogarde, though laboured, is also a masterpiece. It includes the famous adagio by Mahler, with whom Mann was acquainted.

Mann seems to have known almost everyone who was anyone in his time, and was very catholic in his tastes and company. He remains, however, a crucial bridge between the tradition of nineteenth century letters and the twentieth century. Indeed, the earlier novels referenced above may appear at times like caricatures of that tradition.But great aestheticism does not necessarily equate to human greatness.

As alluded to, Mann was a supporter of Kaiser Wilhelm during the First World War, and a romantic German nationalist with a lifelong fascination with Nietzsche. He lived for most of his adult life in Munich and his lifestyle consisted of work, an eclectic set of friends and a digression into unconventional Germanic behaviour. He was married to a Jewish woman, Katia, who he adored, notwithstanding a suppressed homosexuality or bisexuality: they had six children.

As a novelist, not only Kafka but also Musil and arguably Broch, are greater twentieth century writers of fiction or prose within the Germanic tradition. But greatness also involves moral influence. Although, there was little until the 1930s to disclose his abundant moral courage, it was almost unparalleled among great writers even including Albert Camus. The stakes were higher.

Colm Toibin’s recently published zeitgeist book on Thomas Mann The Magician (2021) reveals at one level a set of character traits crucial to how he achieved greatness. He was innately Protestant, despite a Brazilian, Catholic mother, modest and hard working. Commenting on his own prose style, Mann said it was ponderous, ceremonious, and civilised. This he said was all that fascists hate.

And boy did he hate them. He hated in fact all forms of human fakeness, lies, deceptions and misinformation; an inclination very evident in the early novel Mario the Magician (1929). He also hated a lack of order and fecklessness, which was apparent in his attitude towards his brother Heinrich. And he hated barbarism.

Thus, the arch conservative of Lubeck, in response to the rise of fascism and barbarism, changed his colour. Like Fernando Pessoa in Portugal, the caterpillar became a butterfly.

The change was gradual. First, he had supported the Social Democrats in the Weimar government, writing treatises on his conversion to socialism as the Nazis emerged triumphant over the course of the 1920s and early 1930s.

Mann simply could not deal with Nazis. At an implicit level, it might have been simply a matter of bourgeois taste, as he had an impeccable personal and aesthetic sensibility and was cosmopolitan but not decadent in his outlook.

In American exile, where he was suspected of harbouring communist views, he was asked about his views on the avowedly communist Bertold Brecht. He said he did not like his writing, but that if he liked a communist writer he would have no problem saying so.

Book burning in Berlin, 10 May 1933.

Exile

On holiday in 1933 he was advised not to return to Germany after many of his books had been burned in the modern day auto–da–fé. It is noticeable that it was mostly the books of Jews and communists that were burnt, but the German Student’s Union, spurred on by Goebbels, also burned Mann’s work.

In Berlin, some 40,000 people heard Joseph Goebbels deliver an address saying:

No to decadence and moral corruption … The future German man will not just be a man of books, but a man of character. It is to this end that we want to educate you. … And thus you do well in this midnight hour to commit to the flames the evil spirit of the past.

Mann was excommunicated as a citizen in 1936. His life was threatened, and he was a moving target for the fascists for the rest of his life. Thus he left Germany when he was almost sixty, and apart from some brief post war visits never returned to reside there again.

One wonders what would have happened if he had been more compliant. He was not Jewish and only a socialist at a stretch. It is possible that they would have showered him with hollow accolades if he had shown more deference. But unlike Martin Heidegger, he did not succumb, and thereafter in exile in Switzerland and America he became a more complete human being, which is reflected in the marked improvement in the quality of the prose thereafter.

His wartime broadcast relayed on the BBC might be regarded as a kind of inverse Lord Haw Haw. On one of his eight-minute broadcasts from 1940 Mann condemned Hitler and his ‘paladins’ as crude philistines completely out of touch with European culture.

In another noted speech, he said: ‘The war is horrible, but it has the advantage of keeping Hitler from making speeches about culture.’

‘Crude Philistines’…

At the end of the war, he refused to allow his nation off the hook. They had turned mad; it was collective hysteria and even the 1945 atrocities documented so well in Anthony Beevor’s Berlin: the Downfall 1945 (2002) were in context to him condonable:

Those, whose world became grey a long time ago when they realized what mountains of hate towered over Germany; those, who a long time ago imagined during sleepless nights how terrible would be the revenge on Germany for the inhuman deeds of the Nazis, cannot help but view with wretchedness all that is being done to Germans by the Russians, Poles, or Czechs as nothing other than a mechanical and inevitable reaction to the crimes that the people have committed as a nation, in which unfortunately individual justice, or the guilt or innocence of the individual, can play no part.

Members of the Hollywood Ten and their families in 1950, protesting the impending incarceration of the ten.

Unamerican Activities…

Extremism cuts both ways. In exile he was forced to testify before the House for unamerican activities as a suspected communist. Here is how he responded:

As an American citizen of German birth, I finally testify that I am painfully familiar with certain political trends. Spiritual intolerance, political inquisitions, and declining legal security, and all this in the name of an alleged ‘state of emergency’. … That is how it started in Germany.”

Moreover, when Mann joined protests the jailing of The Hollywood Ten and the firing of schoolteachers suspected of being Communists, he found ‘the media had been closed to him.’ Finally, he was forced to quit his position as Consultant in Germanic Literature at the Library of Congress, and in 1952, he returned to Europe. Th Overton window of the thought police fell on the great writer, as it does to many today. He was now nearing eighty years of age.

Exile created both a looseness and precision of prose style. A spring in the step. Dr Faustus (1947) is one of the best books ever written. It is a masterpiece and worthy of Broch or Musil or indeed Kafka. The stilted Germanic prose style becomes freer. The theme inspires: good versus evil.

The book is about the composer Leverkuhn who sells his soul to the devil. The Faustian pact is Fascism. It is also about the corrupting influence of atonal music and its nihilistic dissonance which creates a valueless universe, like the structuralists and deconstructionists of our time. The great prose meister was having none of it.

In my view, Dr Faustus is also about Martin Heidegger the other central intellectual figures in Germany at the time. Heidegger fell for the bait and took all the Nazi accolades, entering the Faustian pact despite his Jewish mistress Hannah Arendt, who wrote eloquently subsequently about the banality of evil. Mann, though a man of considerable means, said no.

A theme central to his existence was that an artist cannot abandon politics at least not in such a period as the 1940s, and must recognise the moral consequences of his actions.

Dr Faustus frequently references Leverkuhn’s veneration of Albrecht Durer, the great Renaissance artist, and his pictorial representations of moderation, judgment, melancholia and the apocalypse. Indeed, as the Nazi state collapses, he becomes obsessed with melancholia.

In the search for spirituality, Mann invokes in a man who has lost all reason and his soul. When composing Dr Faustus, Mann showed and lectured on this to a fourteen-year-old girl who was visiting, who was Susan Sonntag. Thus, the magician bridges generations and resonates through the ages.

And then at the end of Days with the light dimming he showed in his book about the conman Felix Krull the darkly comic humour at the heart of capitalist chicanery, which, if left unchecked, culminates in fascism.

Mann is the great Protestant Germanic intellect of the last century, but he was also an ethereal magus and magician.

His legacy lies in the assertion of standards, of discipline, of stable family values, and of a certain amorphous sexuality. Above all it is in the condemnation of extremism, the condemnation of barbarism, the assertion of civilised values, the rejection of censorship, the hatred of chauvinism and the social cleansing from the left or right. A consistent hatred of intolerance from all sides.

That is what is needed now.

His life is also an example of moral courage. The Germans wanted the magician back, but he was not satisfied that they had changed. It was him judging them not them judging him. He did not think they were displaying appropriate contrition for what they had done. He was right.

In a different context, in Chile, when Pinochet was forced to call an election – as our conservative rulers will soon be required to in Ireland – a persecuted advertising expert advised the opposition as to how to orchestrate a campaign. No reference to mass murders or internment camps, just young Chileans with the slogan JUST SAY NO.

That is what Mann said to fascism, and what we must now say to the ruling parties in Ireland. No images of homelessness, no incessant exposure of state corruption and criminality. JUST SAY NO, before it is too late.

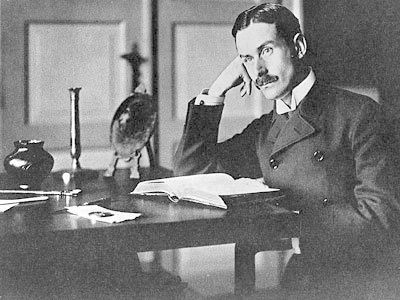

Feature Image: Thomas Mann in 1905.