A fundamental difference between modern dictatorships and all other tyrannies of the past is that terror is no longer used as a means to exterminate and frighten opponents but as an instrument to rule masses of people who are perfectly obedient.

Hannah Arendt, The Origins of Totalitarianism (1966)

It is, perhaps, notable that as a young student Hannah Arendt was the Nazi-sympathising philosopher Martin Hedeigger’s lover. His little Jewess trophy, perhaps redolent in his mind of Weimar Republic decadency. Surprisingly, she never really developed a hated for him, intellectually at least, despite his stunning failure in selling his soul to the Nazis.

In contrast to Heidegger, the ultra-conservative German burgher Thomas Mann chose exile. His rather clunky prose is excused on that point alone, and, suitably, his best work arrived after decamping to Switzerland. This includes especially Doctor Faustus (1947) an oblique portrayal of an actor and academic visited by a Mephistophelian figure, who sells his soul to the Nazis – a Heideggerean type in fact.

Arendt’s background, steeped in the great German philosophical tradition, but rejected as a Jewess – and even subjected to a period under Gestapo confinement – gave her an unparalleled vantage on the great evils of the twentieth century, and the perils of ideological conformity that corrupted even the most elevated intellects. A failure to exercise a moral conscience in performing actions is a recurring failure, even where we do not see the extremes of totalitarian rule.

Arendt and Albert Camus

Arendt is among the most important public intellectual of our age for a variety of reasons.

First, she witnessed at first hand the rise of antisemitism in Germany, before migrating to the Americas, along with others from a golden generation of great mitteleuropean thinkers – many of them also Jewish – such as Stefan Zweig, Joseph Roth, Berthold Brecht and Walter Benjamin. She was young and resilient enough to avoid the despair that led many to suicide, or to expire prematurely like Louis Althusser, whose structuralist influence has had a less than positive influence.

A migratory professor with lifestyle “issues” including a nicotine habit that has become increasingly unacceptable in America, Arendt’s cosmopolitan “Europeanness” was tolerated in her time. In a bygone age the Frankfurt School colonised American academia, and a person such as Vladimir Nabokov – a different beast altogether – could became a professor in Columbia. Imagine the uproar if his Lolita was published today?

Albert Camus in 1957 by Robert Edwards

In some respects her Gallic twin – and the other indispensable public intellectual for our time – Albert Camus also disavowed extremism, strict ideological conformity and what may be described as scientism. Both firmly rejected a positivism identified with the nineteenth century philosopher Auguste Comte (d.1857), whose conclusions according to Camus ‘are curiously like those finally accepted by scientific socialism.’

According to Camus, Comte conceived of a society whose:

[S]cientists would be priests, two thousand bankers and technicians ruling over a Europe of one hundred and twenty million inhabitants where private life would be absolutely identified with public life, where absolute obedience ‘of action, of thought, and of feeling’ would be given to the high priest who reign over everything.[i]

As today we hang on the pronouncement of anointed scientists who decide our intimate social lives, it would appear Comte’s vision has come to fruition. Thus, one of the latter-day hierarchy, Professor Niall Ferguson in an interview with The Times revealed his amazement at the power he wielded. After the British government followed Chinese policy in introducing a lockdown he observed: ‘It’s a communist, one-party state, we said. We couldn’t get away with it in Europe, we thought. And then Italy did it. And we realised we could.’

Likewise, Arendt equated Comte’s hope for ‘a united, regenerated humanity under the leadership – présidence – of France’[ii] with the idea of a ‘national mission’ used by English imperialists to justify global expansion during the late nineteenth century. Arendt also pointed to the danger of the positivists’ assumption – evident in totalitarian Soviet propaganda – ‘that the future is eventually scientifically predictable’.[iii]

Eichmann in Jerusalem

Eichmann on trial in 1961.

Arendt’s fame rests especially on the proverbial shitstorm caused by her coverage of the former SS officer Alfred Eichmann’s trial in Jerusalem in 1961. She coined the immortal phrase ‘the banality of evil’ to describe how under Nazism ambitious functionaries and bean counters – such as Eichmann – climbed career ladders without regard for the supreme brutality of their regime. This was not apparent to them in their day-to-day lives; so out of sight was out of mind. In any age, including this, we should be wary of a cost-benefit analysis of life where board room decisions decide the fate of human beings and the natural world.

Indicatively, in Ireland between 1996 and 2012 the number of qualified accountants grew by a staggering eight-three percent to number 27,112.[iv] It is now clear that bean counters and bureaucrats dominate our lives. Although many may not seem like villanous characters, any buffoonery on display should not be a source of reassurance. As Arendt describes Eichmann:

Despite all the efforts of the prosecution, everybody could see that this man was not a “monster,” but it was difficult indeed not to suspect that he was a clown. And since this suspicion would have been fatal to the entire enterprise [his trial], and was also rather hard to sustain in view of the sufferings he and his like had caused to millions of people, his worst clowneries were hardly noticed and almost never reported.[v]

Eichmann in Jerusalem highlights how an obsession with compliance and promotion blunts moral sensibility; and how a cognitive dissonance takes hold where slavish obedience leads to a failure to question one’s actions. This is the moral corrosion generated by a lack of consequentialist or moral thinking.

The Human Condition

I would argue that The Human Condition (1958) is central to understanding our age, in that it emphasizes the good life, and a need for Aristotelian measure and moderation in pursuit of eudaimonia. As the opening sentence of Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics puts it: ‘Every art and every scientific inquiry, and similarly every action and purpose, may be said to aim at some good.’

The Human Condition emphasizes a moral conscience that should ideally inform all our actions, especially politics. And she warns of a detachment from human realities that may occur once the “pensionopolis” of an entitled state class have no concern for trade or manufacturing:

No activity that served only the purpose of making a living, of sustaining only the life process, was permitted to enter the political realm, and this at the grave risk of abandoning trade and manufacture to the industriousness of slaves and foreigners, so that Athens indeed became the “pensionopolis” with a “proletariat of consumers”[vi]

It is insufficient to perform a deed in isolation; you have to understand what you are doing and for whom and why. Or at the least investigate and interrogate your motivations, while avoiding the pitfalls of perfectionism. As Voltaire put it: ‘the best is the enemy of the good’, a point seemingly lost on certain scientific authorities in their utopian pursuit of ZeroCovid.

Arendt also warns against the scientism in our public discourse, or more crucially the triumph of a form of mathematical intelligence, which is often divorced from moral decision-making, with Oppenheimer’s quotation from the Bhagavad-Gita ‘Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds’ after the launch of the atomic bomb an obvious statement of this pitfall.

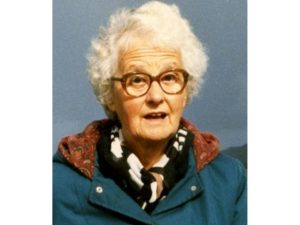

It is a point the philosopher Mary Midgley (above) has also made in response to a letter Albert Einstein wrote to the wife of a deceased physicist that ‘people like us, who believe in physics, know that the distinction between past, present and future is only a stubbornly persistent illusion.’[vii]

It is a point the philosopher Mary Midgley (above) has also made in response to a letter Albert Einstein wrote to the wife of a deceased physicist that ‘people like us, who believe in physics, know that the distinction between past, present and future is only a stubbornly persistent illusion.’[vii]

In response Midgley wrote:

if reality was indeed something that only physicists could reach – if everybody else was wandering clueless through a hopeless maze of illusions – there would be a crucial difference between these scientists and the rest of us. We are being told that we are mere peasants, helpless “folk-psychologists”, and we may well hear this dictum as a simple insult “you are nothing.”[viii]

Thus Arendt, along with Midgley, warns against placing too great a premium on mathematical intelligence – and those who may consider lesser mortals as mere nothings. Arguably, this can be seen in the all-too-ready acceptance of Professor Ferguson’s doomsday mathematical modelling for Covid-19 mortality last year, which proved to be wrong by a significant margin. According to Mark Landler and Stephen Castle in the New York Times, Ferguson’s interpretation was ‘treated as a sort of gold standard, its mathematical models feeding directly into government policies.’

More widely, the contemporary veneration of science has spilled into worship of the ‘dismal science’ of economics, and the triumph of homo economicus. This represents a negation of critical human identity through a hyper-inflated economic reality of survival. That any critical intelligence endures, divorced from corporate ‘influencers’, is almost a minor miracle.

The Human Condition also ably demonstrates that when the sphere of political engagement and the public sphere become redundant and private interests control democracy, then it has given way to something else

Technocracy

Arendt warns of the dangers of technocracy, pointing to the blunted moral conscience of an Eichmann, who reasoned that he was only putting people on trains, and did not have the intellectual curiosity to consider their destination and the likely outcome, or was casually indifferent. Arendt understood that he was more concerned with consorting with powerful people, and networking in a moral oblivion. One might add that being exclusively within one’s own silo bubble, or online echo chamber – as all too many are today – is recipe for serious trouble.

Likewise, Jurgen Habermas has warned of the danger of technocratic solutions devoid of a moral compass, coining the phrase the public sphere.

Juergen Habermas

To offset growing consumerism Arendt advocates the Vita Activa of civic engagement. She remains even-handed, recognising that scientists should of course be listened to – providing crucial specialisation – but it should be understood that many lack a moral or philosophical education, and without ethical training ultimately hold no allegiance to the truth.

In our time, all too often, political debates reach a point of paralysis in endless arguments over statistics; we are to quote Peter Greenaway ‘Drowning By Numbers’. Arendt’s analysis demonstrates how number can give rise to anti-humanism, perfectionism including an obsessions with tidiness, and other forms of anal retentiveness that inhibit our development as human beings.

Science detached from philosophy is divorced from ethical considerations, and thus can be deployed for great evil. Therefore, ‘totalitarianism appears to be only the last stage in a process during which ‘science’ [has become]an idol that will magically cure the evils of existence and transform the nature of man.’[ix]

Banner of Stalin in Budapest.

The Origins of Totalitarianism

The Origins Of Totalitarianism (1951) is the seminal account of twentieth century totalitarianism – as distinct from the ‘mere’ fascism of figure such as Mussolini – of both the Nazis under Hitler and Communism under Stalin. It offers a series of reflections that should serve as a warning in our time – when we cannot be said to live under totalitarianism – but where, nonetheless, an unmistakable shift has occurred in the relationship between the state and the individual. Thus measures that no government would previously have contemplated – from lockdowns to curfews – have been normalised in many countries, and controls have even been tightened in Ireland at precisely the point when a declining number are dying from the disease. Coincidentally, ‘terror increased both in Soviet Russia and Nazi Germany in inverse ratio to the existence of internal political opposition.’[x]

We cannot overlook the damage of enforced social isolation, as Arendt put it:

What prepares men for totalitarian domination in the nontotalitarian world is the fact that loneliness, once a borderline experience usually suffered in certain marginal conditions like old age, has become an everyday experience of ever-growing masses of our century.[xi]

Arendt also well understood the fictions that underpin our understanding of the world, and a tendency to embrace conspiratorial ideas in the absence of reasonable explanations:

Legends have always played a powerful role in the making of history. Man, who has not been granted the gifts of undoing, who is always an unconsulted heir of other men’s deeds, and who is always burdened with a responsibility that appears to be the consequences of an unending chain of events rather than unconscious acts, demands an explanation and interpretation of the past in which the mysterious key to his future seems to be concealed. Legends were the spiritual foundation of every ancient city, empire, people, promising safe guidance through the limitless space of the future. Without ever relating facts reliably, yet always expressing their true significance, they offered a truth beyond realities, a remembrance beyond memories.[xii]

Thus, it is essential that in responding to the damage of contemporary social atomisation that we do not succumb to ideologies that sow further division.

Arendt observed how allegiances break down when Populist mobs gain traction. Initially the targets are those of no influence or assets, but essentially anyone is guilty under the arbitrary laws of totalitarianism in power. Thus she recalls:

It is obvious that the most elementary caution demands that one avoid all intimate contacts, if possible – not in order to prevent discovery of one’s secret thoughts, but rather to eliminate, in the almost certain sense of future trouble, all persons who might not only who might have an ordinary cheap interest in your denunciation but an irresistible need to bring about your ruin simply because they are in danger of their own lives.

Sadly, this agitation seems reminiscent of the states of mind actually cultivated by government scientists, who have deployed ‘fear, shame and scapegoating to change minds is an ethically dubious practice that in some respects resembles the tactics used by totalitarian regimes such as China,’ according to Gary Sidley, a retired clinical psychologist. Nowadays, instead of being imprisoned, we contend with social shame and even loss of a job for heinous crimes such as meeting a friend for a pint or taking a hill walk.

Radical Evil

Arendt observes a failure ‘inherent in our entire philosophical tradition’ to conceive of a radical evil.[xiii] Such a blind spot she argues means, ‘Totalitarian solutions may well survive the fall of totalitarian regimes in the form of strong temptations which will come up whenever it seems impossible to alleviate political, social, or economic misery in a manner worthy of man.’[xiv]

Moreover, it is important to note in our present state of enforced isolation:

[I]t has frequently been observed that terror can rule absolutely only over men who are isolated against each other and that, therefore, one of the primary concerns of all tyrannical governments is to bring this isolation about. Isolation may be the beginning of terror, it certainly is its most fertile ground, it always is its result.[xv]

So let us be wary of the strongman leaders who have emerged to ‘guide’ us to the promised land during a pandemic, which shows up the damage of their own making; and who now argue that solutions lie in asserting the very neoliberal values that brought us to this impasse in in the first place.

'Greed' and 'capitalism' helped UK's vaccines success, UK PM Boris Johnson says https://t.co/foVLlLIDPX

— BBC News (World) (@BBCWorld) March 24, 2021

Sadly Burkean and Habermasean moderation has been lost in an age of tribal nationalism. The handmaiden’s of the strongman leaders are in fact a grasping “pensionopolis” that are removed from the dramatically worsening poverty in countries such as Ireland caused by the pandemic.

This sadly is the digital generation of what are, in effect, fabricated human identities – a kind of unreal Blade Runner replicant. Homo faber has given way to homo economicus, as the law and economics ideologues put it. Craftsmanship and intellectualism are despised, and the public space denuded of significance.

Finally, and perhaps more optimistically, Arendt clearly distinguishes between loneliness, and solitude: ‘Solitude requires being alone, where loneliness only shows itself most sharply in company with others.’ Let us thus endeavour to accept solitude as a temporary gift and resist the loneliness which is fertile ground for the infliction of terror.

[i] Albert Camus, The Rebel, Translated by Anthony Bower, Penguin, London, 2013, p.145

[ii] Hannah Arendt, The Origins of Totalitarianism, Penguin, London, 1966, p.237

[iii] Arendt, Ibid 1966, p.454

[iv] Tony Farmar, The History of Irish Book Publishing, Stroud, The History Press, 2018, p.12

[v] Arendt, Eichmann in Jerusalem, Viking Press, New York, 1963, p.55

[vi] Hannah Arendt, The Human Condition, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1958, p.37

[vii] Mary Midgley, Are You an Illusion, p.136

[viii] Beard, Ibid, p.138

[ix] Arendt, Ibid 1966, p.453

[x] Arendt, Ibid, 1966, p.514

[xi] Arendt, Ibid, 1966, p.627

[xii] Arendt, Ibid, 1966, p.271

[xiii] Arendt, Ibid, 1966, p.602

[xiv] Arendt, Ibid, 1966, p.603

[xv] Arendt, Ibid, 1966, p.623