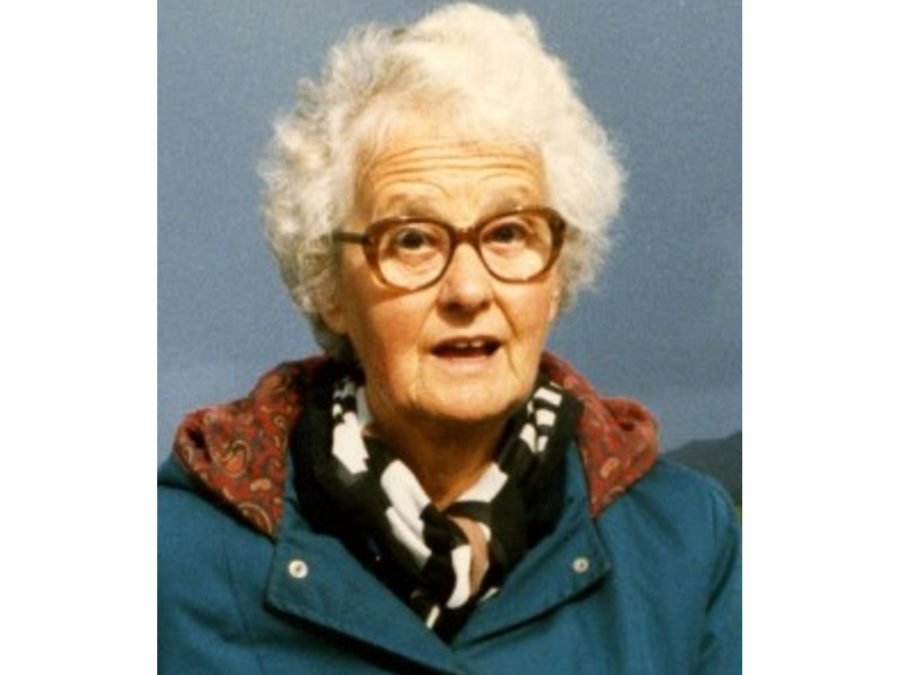

Mary Beatrice Midgley was a giant among philosophers, though she only published the first of her nineteen books at the age of fifty-nine, a feat which is unfathomable today in more than one respect. That anyone could start so late and produce so much, and so vibrantly (she produced in addition over two-hundred-and-eighty articles) is close to miraculous – her last book What is Philosophy For? appeared just a few days before her ninety-ninth birthday. But more than that, that a philosopher could wait until she was actually ready to say what she wanted to say is something that is hardly permissible today – ‘I wrote no books until I was a good 50, and I’m jolly glad because I didn’t know what I thought before then’, she explained.

Mary was an adult among adolescents, but she remained in a permanent state of youthful rebellion. One of the constant themes of her work is meta-philosophical. ‘Despite its irritating features’ she tells us, ‘philosophy is not a luxury but a necessity’. Humans need philosophy whenever things get difficult: politically, ethically, personally, psychologically, scientifically, emotionally. Any area of the messy, brilliant, muddle that is human life can be an occasion for puzzlement or anxiety, and this is where philosophy, with its ability both to get down to the nitty gritty and to bring the big picture into view, comes in handy. It is not an affair reserved for the ivory tower but an activity as much part of human life as raising children or preparing food.

Philosophy ought not to be produced hastily to satisfy assessors or auditors. Work of that sort, Mary observed, is almost bound to be negative — to work quickly one must almost invariably accept the background assumptions of predecessors and complain only about the details. In contrast, Mary’s work, and her view of philosophy in general, was both positive and holistic; while the philosopher needs something of the doggedness and rigour of the lawyer, she also needs the vision of the poet; to be able to see how things connect, to understand how thought gets mired in confusion when the myths in terms of which certain concepts are intelligible no longer serve us. And in this case what is needed is an ability not only to diagnose but to create– myth, image and metaphor. Mary’s exemplification of her own image of what philosophy should be, and involves, was peerless. Her prose was starlit by quick and vivid turns of phrase that took thought in new directions. Philosophical argument, she writes in her last book, is more like chasing rabbits than mining for nuggets of gold.

Two myths that no longer serve us resurface in Mary’s work repeatedly; the myth which see humans as opposed to animals, and, relatedly, the myth of the social contract which pictures us all as unconnected to each other as atoms stranded in the void. (Mary reminds us that the myth was created for seventeenth century male house-holders performing their civic duty on behalf of their household: it forms part of the background picture against which female emancipation seemed to many incoherent).

Both myths, transposed to the contemporary scene, are destructive to human life, and the task of the philosopher – whom Mary compares to a plumber – is to sniff out the problem and to replace stagnant concepts with those that aid the flow our thinking and living. In picturing human in opposition to beast, we constrain possibilities for theorizing and acting in relation both to each other and to animals. If we change the picture and think of ourselves instead as a kind of beast—a human kind—we open up a different ethical vista. We might now recognize each other as creatures of passion, instinct and habit (as much as creatures of reason) and—as Cora Diamond has put it—also come to see other animals as our fellows.

Likewise, in thinking of ourselves as featureless individuals or egos, loci of choice and unconstrained liberty, we dishonor and fail to make central in our philosophical theorizing the material reality that should be our very topic: how to live, and how, as human animals, social animals, we are radically and essentially dependent on each other. Mary’s work teaches us, reminds us, that our lives are held together through all manner of affective ties, fragile and precious, sometimes volatile, as well as the bounds of friendship and love. And this insistence brings into view another current of Mary’s thinking. Traditional philosophical ways of thinking about the human subject are gendered. A philosophy that falsifies women’s experience is bad philosophy.

In turning again and again to the human scene, our shared forms of life, our human nature, and our capacities to create myth, image and narrative, Midgley evinced a philosophical attitude characteristic of three other distinguished moral philosophers of the last century, all of whom were her contemporaries at Oxford during World War II: Iris Murdoch, Philippa Foot and Elizabeth Anscombe. All these writers, like Midgley, are recognised as re-appropriating a classical emphasis, derived from Plato and Aristotle, on human nature and virtue, which they then electrified with the teachings of Wittgenstein. In the years immediately following the war, the Quartet met regularly at Philippa Foot’s house in north Oxford to discuss the orthodoxies of the day, which, as Midgley wrote recently, they saw as disastrous and to which they voiced a unanimous and joint “No!’.

This story of the Quartet is important, not just from the perspective of gender activism in philosophy, but because it reminds us of precisely those facts that Mary’s philosophy makes so plain. Philosophy, like human life, is not a pursuit for an isolated individual but for a group, a collective, a gang. An isolated thinker soon becomes drawn to fantasy, consolation, and narcissism: this group of friends in Philippa Foot’s living room remained firmly grounded in reality.

The collaborative nature of philosophy is something that Mary has taught us, not only by her writing but by inviting us into her living room, where for the last three years we have regularly shared tea and biscuits and talked about topics as various as G. E. Moore, octopi, and Brexit. Mary animated the past for us as she painted vivid pictures of herself and her friends discussing Plato’s forms, plotting against R. M. Hare, ice-skating on the frozen Cherwell. She helped to make real the philosophy of A. J. Ayer and J. L. Austin by locating it in space and time. But these conversations, so precious to us now, became something more than philosophical ‘research’ (a label Mary despised).

As our friendship with Mary grew we came to rely on her sane, wise and philosophical outlook to help us not only with our work but with our lives. Philosophy as therapy came to life in Mary. In her living room our gripes about the impact agenda, the marketisation of the University and the pressures of the REF were transformed into occasions for philosophical work, historical reflection and calls to action: ‘Well, what are we going to do about it?’, she would ask.

Mary’s imagination and sense of a job to be done remained inexhaustible even as her bodily frailty diminished her physical territory to a couple of small rooms in Jesmond, Newcastle. Philosophers around the world were sent missives from her computer—‘Is history of philosophy still being taught?’, ‘Is it true that no-one reads Kant these days?’, ‘How can I find out more about Transhumanism?’. And she would send us out on missions too, waiting patiently for reports, while we went about looking in archives, chasing references, interviewing friends and giving talks about the Wartime Quartet (or, as Mary suggested, the Re-Socratics). We are terribly sad that we won’t have a chance to tell Mary about our latest trip to the Anscombe Archive in Philadelphia (‘Find out about Elizabeth’s family’, we were instructed. ‘We absolutely must know what was going on there!’).

Something feels strangely amiss in the idea of an ‘Obituary’ for Mary Midgley – not least of all the discovery that Mary was not, after all, immortal. An obituary gives notice of an ending. It does so by isolating an individual, treating her as a single organism whose complete life can now be told. But Mary’s story and the story of her contribution to philosophy is, for us, only just beginning. That story places Mary back in her context, among friends, one dazzling half of a hundred conversations still unfinished—she was writing to collaborators on the morning of her death. Those conversations must now go on with new interlocutors and under these sadder conditions. It is up to us to weave Mary’s work into our intellectual lives and in doing so make it part of a continuous shared effort to ‘make sense of this deeply puzzling world’.

This article was originally published for the Insitute for