Unlike Bob Dylan who is still actively making music, Leonard Cohen has not released a new song from beyond the grave. Cohen is dead. Of course he was from an older generation than Dylan.

If Dylan represents the Baby Boomers then the Canadian national poet and songster represents the preceding Beat or Beatnik generation of Kerouac and Ginsberg, which he, and Dylan, reference frequently.

Cohen and Dylan are the two central figures of a movement in popular, or folk, music, which morphed into cultural commentary and public intellectualism. Thus, the troubadour or bardic poet jumped the tramlines from pop musician into serious art. Dylan was rewarded with a Nobel Prize, but many thought it should have gone to Cohen. While Dylan is a poet in a minor key dedicated to the craft of songwriting, Cohen was a major poet, who learned his trade, and novelist – Beautiful Losers (1965) is a hidden treasure – and that poetic sensibility is reflected in his measured songwriting.

With Cohen a poem such as the stunning ‘Going Home,’

I love to speak with Leonard

He’s a sportsman and a shepherd

He’s a lazy bastard

Living in a suit

Becomes ‘Old Ideas’ (2012) a song.

This genre hopping perhaps explains why Cohen’s style is less prolix or baroque than Dylan’s, although both arrive at a point of brief severity, and a compression of language which is to be admired. There are other similarities, such as both mining the political protest genre.

The Influence of Lorca and Spain

As an aspiring young poet, and through much of his career, Cohen was influenced by Federico García Lorca and the sense borrowed from Lorca of Duende, a Spanish term for a heightened state of emotion, expression and authenticity, often connected with Flamenco music. In fact the famous song ‘Take This Waltz’ is a translation of a Lorca poem. As he put it in an acceptance speech for the Prince of Asturias Award in 2011:

Now, you know of my deep association and confraternity with the poet Federico Garcia Lorca. I could say that when I was a young man, an adolescent, and I hungered for a voice, I studied the English poets and I knew their work well, and I copied their styles, but I could not find a voice. It was only when — when I read, even in translation, the works of Lorca that I understood that there was a voice. It is not that I copied his voice; I would not dare. But he gave me permission to find a voice, to locate a voice; that is, to locate a self, a self that that is not fixed, a self that struggles for its own existence.

The speech is a beautifully crafted admixture of jokes and seriousness, reflecting an interior monologue of his love of Lorca and Spain, but acutely conscious of shall we say some of the sensitivities of his audience.

He also reveals how a Spanish guitar teacher in the space of three lessons taught him the rudiments of Flamenco that proved crucial to his style:

He said “Let me show you some chords.” And he took the guitar and he produced a sound from that guitar that I’d never heard. And he — he played a sequence of chords with a tremolo, and he said, “Now you do it.” I said, “It’s out of the question. I can’t possibly do it.” He said, “Let me put your fingers on the frets.” And he — he put my fingers on the frets. And he said, “Now, now play.” It — It was a mess. He said, “I’ll come back tomorrow.”

As he put it: ‘It was those six chords — it was that guitar pattern that has been the basis of all my songs and all my music.’

Sadly after completing this initiation Cohen discovered that his mysterious teacher had taken his own life:

I knew nothing about the man. I — I did not know what part of Spain he came from. I did not know why he came to Montreal. I did not know why he stayed there. I did not know why he he appeared there in that tennis court. I did not know why he took his life. I — I was deeply saddened, of course.

Early Songs

The initial albums stemming from his poetry are a chronicle of loners, romantic love, beautiful losers – to use the title of his defining 1966 book – and are decidedly non-political. They are a kind of erotic tablet and backdrop to a very different age.

The songs are a soundtrack to Robert Altman’s masterful revisionist Western ‘McCabe and Mrs. Miller’ (1971) in which the doomed love of the interloping property baron (played impeccably by Warren Beatty) and the hooker with a heart (played by Julie Christie).

It is a film of stunning autumnal clarity and candour but wistful nevertheless. We meet a bygone age, though strangely redolent of our age of boom and bust. Gentleman outsider capitalists should be wary of their surroundings. Will of the wisp behaviour. As we will see Cohen saw these hard times coming.

Those songs of romantic disappointment such as ‘So Long Marianne’ and ‘Suzanne’ are often hymns to ex-lovers. Cohen was a ladies’ man which probably brought some reputational damage. Although thankfully he was Canadian rather than Irish, otherwise this sensuality would have been crucified.

He seems to have required muses in orbit to function creatively. The well of inspiration was often carnal or at least he needed the mother lode to function.

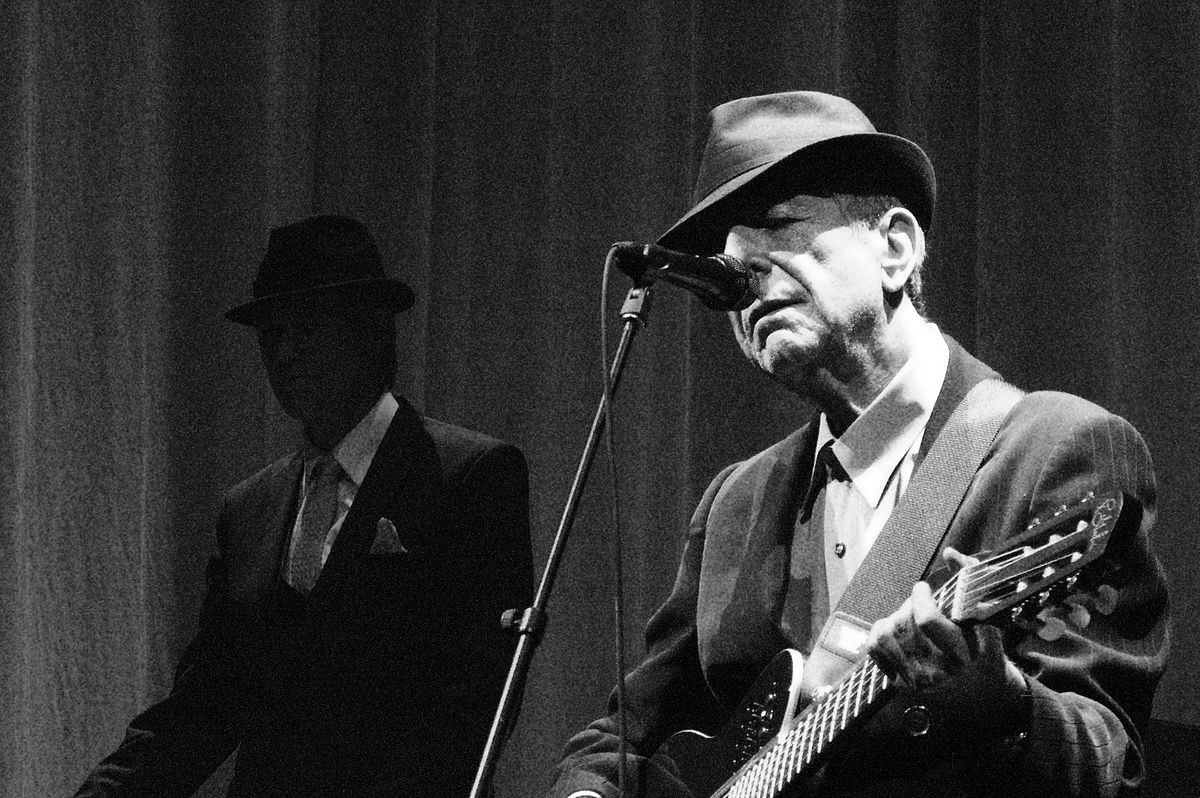

In his famous comeback tours, after being liquidated by a dodgy business partner, he was surrounded on stage by a bevy of ex-lovers and chanteuses, at least when I saw him in Kilmainham in Dublin. He collaborated with some and slept with others. Surprisingly these ex-lovers did not seem to resent him. By all accounts he was a charming man and curiously self-reflexive about his predilection for the other sex, best captured in ‘Death of a Ladies Man’.

By all accounts, including the way he treated his children, he was in general a lovely man. Yet those earlier songs have almost become caricatures. It is the later songs, particularly those after he came back from the Buddhist retreat that gain the most traction.

Hallelujah and Politics Protest Songs

Perhaps the defining song of that pre-retreat period was ‘Hallelujah’ (1984), memorably covered by Jeff Buckley, the suicidal chanteuse of incompletion. The blending of the spiritual and the erotic are well captured in the opening stanza.

I heard there was a secret chord

that David played and it pleased the Lord

But you don’t really care for music, do you?

And then God and faith but faith in romance and carnality:

Well your faith was strong but you needed proof

You saw her bathing on the roof

her beauty and the moonlight overthrew you

And an intense religious ambiguity:

Maybe there’s a God above

but, all I’ve ever learned from love

was how to shoot somebody who outdrew you?

It is a spiritual odyssey and not for the last time a conversation between Cohen and God, although in the case of Cohen a belief in the divine was Buddhist, hence the ill-advised decampment to a Buddhist monastery ostensibly to see out his end of days. His work tells of a spiritual journey evoking a divine disapproval that might be traced to the Jewish tradition.

I saw Jesus on the cross on a hill called Calvary

“Do you hate mankind for what they done to you?”

He said, “Talk of love not hate, things to do – it’s getting late.

I’ve so little time and I’m only passing through.”

I sense that Cohen believed that God, if he exists, thinks of him as a naughty boy and recalcitrant artist. It is vastly different to Dylan’s political engagement or indeed Dylan’s much more fearful and eschatological sense of God. So Cohen was spiritual, but not a defined believer. A fence sitter.

The political songs come later and are as angry as Dylan’s. ‘Democracy’ (1992) sounds an initially optimistic note:

It’s coming through a hole in the air

From those nights in Tiananmen Square

It’s coming from the feel

That this ain’t exactly real

Or it’s real, but it ain’t exactly there

From the wars against disorder

From the sirens night and day

From the fires of the homeless

From the ashes of the gay

Democracy is coming to the USA

But this move to utter despair in the apocalyptic warnings of ‘The Future’ (1992).

Things are going to slide, slide in all directions

Won’t be nothing

Nothing you can measure anymore

The blizzard, the blizzard of the world

Has crossed the threshold

And it has overturned

The order of the soul

When they said (they said) repent (repent), repent (repent)

I wonder what they meant

When they said (they said) repent (repent), repent (repent)

I wonder what they meant

When they said (they said) repent (repent), repent (repent)

I wonder what they meant

You don’t know me from the wind

You never will, you never did

I’m the little Jew

Who wrote the Bible

I’ve seen the nations rise and fall

I’ve heard their stories, heard them all

But love’s the only engine of survival

Your servant here, he has been told

To say it clear, to say it cold

It’s over, it ain’t going

Any further

And now the wheels of heaven stop

You feel the devil’s riding crop

Get ready for the future

It is murder

It’s a dirge worth quoting in full that is redolent of doom, and a world disorder upon us. God is more readily embraced, but as in Dylan’s album Slow Train Coming (1980) we have met the God of retribution and vengeance. The God of the Old Testament.

The only song of equivalent outrage in Dylan’s oeuvre are possibly ‘Hurricane’ (1975), and certainly the recent song about bankers ‘Early Roman Kings’ on Tempest (2012).

Cohen’s ‘Closing Time’ (1992) also senses the end of days and that the shooting match is over.

loved you when our love was blessed

I love you now there’s nothing left

But Closing Time.

However, my favourite song and to my mind his greatest work is ‘Dance Me To The End Of Love’ (1996). I listen to it regularly and I find it most apt for our times.

Today we seem like shadow dancers, ghosts, marionettes spinning towards oblivion. It is most relevant to our plague-driven times.

Dance me to the children who are asking to be born

Dance me through the curtains that our kisses have outworn

Raise a tent of shelter now, though every thread is torn

Dance me to the end of love

So Cohen still has much to say from beyond the grave, and his death left popular song without one of its titans. Dylan now almost has the stage to himself as a probing popular commentator in this genre.