Irish Times health correspondent Paul Cullens reported on February 13, 2023 that a disturbing 1,300 patients had ‘died over the winter as a result of delays in hospital admission from emergency departments, according to an analysis of Health Service Executive data.’

This followed a longer article by Cullen the previous Saturday exploring what is driving the deeply concerning excess death figures recorded over the previous year in Ireland and elsewhere – ‘among worst in 50 years’ according to the BBC.

Importantly, Cullen acknowledges that COVID-19 itself ‘can only explain a fraction of the additional number of people dying.’

Given this is a global issue, attributing additional mortality primarily to the parlous state of emergency medicine in Ireland is a difficult argument to sustain. It could be a contributory factor, but conditions in 2022 were no different to the preceding years. For example, prior to the onset of the pandemic, in January, 2020 Cullen reported that ‘[t]he first week of the new year has been the worst ever for hospital overcrowding, according to figures from the Irish Nurses and Midwives Organisation.’

The first of Cullen’s recent articles, in particular, appears to have been written in response to high mortality being ‘attributed by some online to Covid vaccines.’ He summarises his arguments to the effect that ‘[t]his limited data does not appear to support claims of a vaccine-related rise in deaths in this age cohort.’

He then reveals,

While the vast majority of medical specialists we asked in recent months about claims of vaccine-induced harm say they have no cause of concern, it is fair to say a small number of doctors do, though for now they are reluctant to speak publicly.

This reluctance among members of the Irish medical profession “to speak publicly” about adverse reactions to the vaccines should be setting off alarm bells, but what is really striking about the current coverage of elevated mortality is the detached, clinical tone.

This contrasts starkly with the emotive way in which death, and illness, attributed to COVID-19 was reported during the period of the emergency powers (March 2020 – January 2022).

Stalin (in)famously said the death of one man is a tragedy but the death of a million is a statistic. In Ireland during that period a single death from COVID-19 was treated as a tragedy, whereas today thousands of additional deaths only seem to be eliciting comment when vaccines are implicated.

Frank Armstrong measures the health of the Irish republic in response to the pandemic, and argues for a social contract inclusive towards all who live here.https://t.co/Y2SCYfZab6@frankarmstrong2 @BowesChay @broadsheet_ie @indepdubnrth #COVID19

— CassandraVoices (@VoicesCassandra) May 27, 2021

A Calamity?

Over the course of the pandemic the mean age of death from COVID-19 (as of 09/08/2021) in Ireland was eighty years or older, just two years younger than the average age of death. Four in five deaths from COVID-19 had at least three medical conditions. Revealingly, CSO mortality figures through the years 2018-2020 (2018: 31,116; 2019: 31,134; 2020: 31,765) show little difference between the first year of the pandemic and preceding years.

There remain also serious question marks over how deaths are attributed to COVID-19. The Central Statistics Office (CSO) adopted WHO guidance listing COVID-19 as the underlying cause of death when:

confirmed by laboratory testing irrespective of severity of clinical signs or symptoms.

diagnosed clinically or epidemiologically but laboratory testing is inconclusive or not available.

Chief Medical Officer Tony Holohan acknowledged a remarkably low threshold in April, 2020: ‘Clinically, the “index of suspicion” for the disease would be “a good deal higher” than would normally be the case for flu.’

Even allowing for a high mortality from COVID-19 in the early part of 2021, the death toll of 33,055 for that year – after vaccines had arrived – is striking. The full set of figures for 2022 are not yet available, but the CSO say that in Quarter 2 (Q2) of 2022 there were 2,626 more deaths (39.2%) when compared with the same period in 2021. Assuming that pattern is evident throughout 2022 and beyond then perhaps we should be describing this is as a calamity.

There is now compelling evidence of under-reporting of serious adverse harms from vaccines. However, by January, 2021 the FDA had allowed Pfizer ‘to undermine the scientific integrity of the double-blinded clinical trial’. This means we cannot easily attribute additional deaths to the vaccines. But nor can we rule out the possibility that a significant proportion of excess deaths are an unintended consequence of a treatment that is still being promoted in Ireland for infants as young as six-months-old.

This article, however, proposes another determining cause, which is that heightened stress levels generated by lockdowns and other non-pharmaceutical interventions designed to instil fear of contracting COVID-19, and actively promoted by emanations of the state and mainstream media, are the primary cause of excess deaths in Ireland and beyond.

Frank Armstrong reviews a new book on the Irish government's response Covid-19 and wonders whether it will be said once again: “We didn’t know, no one told us”https://t.co/vikPQsuFMa @broadsheet_ie @danieleidiniph1

— CassandraVoices (@VoicesCassandra) May 25, 2022

Summer, 2020

Even after case numbers and deaths had plummeted by early summer 2020, legacy Irish media remained fixated on COVID-19. Writing for the Irish Times on May 23 clinical psychologist and author Maureen Gaffney reckoned that ‘Covid-19 has scored a direct hit on our most basic psychological drives.’ She seemed oblivious to how statements such as her own that ‘the consequences of the coronavirus pandemic may have changed life more permanently’ might be further stressing out her readers.

Yet the first wave of COVID-19 afflicted few Irish people directly. An “omni-shambolic” testing infrastructure meant it was impossible for most people to determine whether symptoms synonymous with the common cold were COVID-19 or not. Despite early evidence of the unreliability of PCR testing, almost seven hundred million euro would be spent in Ireland on testing over the course of the pandemic.

However, so-called ‘confirmed’ cases (via PCR) appear to have served a purpose beyond diagnostics. Speaking on RTÉ in November, 2021, Dr Deirdre Robertson of the ESRI’s Behavioural Research Unit said one ‘of the biggest predictors’ of social activity has been the level of worry over the virus: ‘As cases have gone up, worry has gone up and that has changed behaviour.’

The authorities seem to have identified a correlation between case numbers and “worry over the virus” which influenced “behaviours”. By maintaining case numbers at a sufficient level through mass testing, worries could thus be maintained.

This perhaps explains NPHET’s almost comical resistance to antigen testing. The availability of these cheap, over-the-counter kits would eventually allow people to self-diagnose, but the results could not be used to induce fear.

It might also be noted that after leaving his post of Chief Medical Officer, Tony Holohan took up a role with Enfer, one of the primary testing provider to the state, which earned €122.4 million in 2020.

Irish people were subjected to unprecedented social atomisation during a first lockdown that extended into the summer of 2020 – beyond most other European countries. Public figures such as then Minister for Health Simon Harris sent out subtly misleading messages, cultivating the idea that the virus was far more deadly than it was in reality.

Our world is now full of statistics and numbers. I wanted to share an important one with you – our latest figures show 19,470 people have recovered from #COVIDー19. That is 84.3% of those who have contracted this virus.

— Simon Harris TD (@SimonHarrisTD) May 13, 2020

Later in 2020, Fianna Fail TD Cathal Crowe referred to ‘a fatality rate at the moment in this country of 6.2% of those who contract Covid.’

However, research by Professor John Ioannidas reveals a far lower pre-vaccination infection fatality rate, especially among non-elderly populations, than previously assumed. This is as low as 0.03% for under sixties. Notwithstanding this easily accessible information, the Irish public were reminded ad nauseum of the ‘deadly’ coronavirus by mainstream media.

Thus, in the summer of 2020 a public address called on bathers to ‘socially’ distance at Seapoint beach in Dublin. Reinforcing the dystopian atmosphere, in July a national mask mandate was introduced, despite a longstanding consensus, confirmed in a recent meta-analysis, that these do not block the transmission of respiratory pathogens.

This generated a distinctively modern Irish form of hysteria – often vented on social media platforms – which found fullest expression in the enraged response to Golfgate at the end of August, 2020.

In hindsight the breaches by politicians were relatively mild. It was the hypocrisy that stung, as people recalled being denied a last visit to a loved one on their death bed. Suppressing a natural human inclination to socialise was putting people in a semi-permanent state of repressed anger.

A nation of obsessive smart phone users was confronted by an unprecedented onslaught of information tailored to stress them out. The only ‘sensible’ opposition to the lockdown policy presented by the mainstream media came in the form of a delusional ZeroCovid movement that promised an end to lockowns by locking down more strictly.

ZeroCovid Ireland's zero-tolerance to the virus shares characteristics with the War on Terror, but the enemy is within and the war unwinnable.https://t.co/Er9rfqGHPI@broadsheet_ie @IlsaCarter1 @wadeinthewate11 @liamherrick @AliceHarrisonBL @VillageMagIRE @ThePhoenixMag

— CassandraVoices (@VoicesCassandra) February 17, 2021

Best in Class

From the outset, Irish journalists and other public figures adopted a best-in-class superiority, contrasting the chaos in Britain under Boris with the virtuous restraint of Irish people. After early prevarication, clean-cut (caretaker) Taoiseach Leo Varadkar struck the right note of gravity as he heroically re-registered as a doctor, having warned of a death toll of 85,000 in a worst-case scenario. Headline writers were uninterested in the best-case scenario.

Mainstream Irish media hardly raised a murmur at an unconstitutional power grab by NPHET. The millions of euros poured by the government into advertising seems to have had a chilling effect, while a pliant national broadcaster was quietly bailed out by the government.

Anyone calling for moderation was subjected to ridicule or attack; guilt by association with Qanon followers calling it a hoax, and who immediately mounted a challenge in the courts to the unprecedented restraints on liberty. Thereafter, anyone calling for moderation was branded far-right.

Independent TD Michael McNamara bravely articulated a sceptical middle ground after chairing the Oireachtas Special Committee on the Covid Response, but to little avail. Despite their unreliability, opinion polls were often taken to represent the will of the people.

A doctor in a Dublin nursing home describes the cruel impact of a chaotic response to Covid-19 https://t.co/lQGN32LwNv

— Denis Staunton 沈俊杰 (@denisstaunton) April 26, 2020

Care Home Deaths

While the virus had little direct effect on Europe’s youngest population, Ireland did witness the second highest proportion of care home deaths in the world during the first wave. To some extent this was a product of an understandable failure to recognise that the virus seems to have been circulating for over a year. Thus, CMO Tony Holohan ordered private care homes to re-open to visitors in early March, 2020.

Less forgivably, testing was withdrawn at the height of the surge, and many older people were removed from hospitals, to create space for an expected onslaught of younger people that never arrived.

The scale of care home deaths revealed longstanding neglect of older people in those setting. A Pandemic Doctor wrote despairingly:

The airwaves and print media are bursting with opinion, analysis and occasional outrage as the crisis unfolds and consumes the institutionalised elderly. The great and the good understand and discuss, sounding wise and all-knowing. But week after week we are alone. Where is the calvary? Where are the boots on the ground? Who is going to help?

Difficulties were exacerbated by staff shortages caused by outbreaks among workers living in crowded accommodation. One resident of a county Meath nursing home – fittingly called Kilbrew – died two weeks after being admitted to hospital with an infestation of maggots in a facial wound.

A "strawman" conspiracy theorist appears to have been developed, especially by so-called fact checkers, to deter valid journalistic enquiry during the pandemic.https://t.co/IvMv3c76Nw@broadsheet_ie @BowesChay @PD03662439 @ciarasidine @LiamDeegan3 @WhistleIRL @FutureVisions5

— CassandraVoices (@VoicesCassandra) February 12, 2022

Lost Lives

Never before in the history of Irish media and politics had there been such unrelenting emphasis on a particular disease, generating what Maureen Gaffney described as ‘our version of the spirit of the Blitz.’ But it was fear rather than resilience that were to the fore.

In June, 2020 RTÉ Investigates ran a two-part documentary called Inside Ireland’s Covid Battle. This stretched the war time metaphor to its limit, bringing the spectre of patients gasping for breath into living rooms around the country, to devastating effect.

You could cut through the paranoia on streets festooned with two-metre markers and yellow-coloured public health notices. Pedestrians would take refuge on to the road to avoid a close shave with another living human being. Joggers became hate figures.

Later in the summer of 2020, the Irish Times launched an emotive Lives Lost Series. It reads: ‘Those who have died in Ireland and among the diaspora led full and cherished lives’; the series was ‘designed to tell the stories behind the numbers.’

These included Richard Brady, an ‘Avid Dubs fan who loved his family dearly’; Ann Hyland, who ‘wrote a children’s book, climbed the Great Wall of China, rode a camel in Morocco, jet-skied in Barbados’; and Vincent Fahy who ‘began his career with ESB ‘putting the light’ into rural areas.

These are touching tributes to ordinary people among a generation that built Ireland as we know it, but these lives were only cherished after their deaths. It begs the question: why are additional people now dying being treated as numbers? Where are the TV cameras to witness them gasping for breath?

The name chosen for the series ‘Lives Lost’ is also instructive. Lost Lives: The Stories of the Men, Women and Children who Died as a Result of the Northern Ireland Troubles is a well-know book containing short biographies of the victims of the Northern Ireland Troubles. It was adapted into a film by the same name in 2019.

The linkage between Lives Lost and Lost Lives is surely deliberate. It conveys the impression that any death from COVID-19 was not really by natural causes, but caused by the terrifying virus.

Over the course of the summer of 2020, the Irish public also became acquainted – via social media – with the phenomenon of Long Covid, or ‘long haulers’, through social media. This too seems to have been used to sustain worry, once many had discovered the low infection fatality rate for COVID-19. Thereafter, mainstream media, including the Irish Times and RTÉ, ran a series of articles emphasising the struggles of previously healthy individuals suffering from Long Covid.

It is notable that no hue and cry was raised by the mainstream media when the Mater Hospital lost its fight to maintain a Long Covid clinic in late 2022.

‘We Need a Reckoning’

Considering the calamitous excess deaths we are now witnessing, Irish society ought to be reflecting on the efficacy, and morality, of adopting the lockdown-to-vaccination policy promoted by the WHO. What Maureen Gaffney referred to as ‘Our version of the spirit of the Blitz’ may come to be regarded as the most damaging public health intervention in history – the military equivalent of turning guns on ourselves.

In a powerful video message called ‘We Need a Reckoning’, the Indian writer Arundhati Roy describes the infliction of a two month lockdown on her country as a Crime Against Humanity causing untold suffering to millions of impoverished workers in particular. Ireland needs a reckoning too.

In his article on excess deaths, Paul Cullen at least acknowledges that ‘many non-Covid deaths arose from the pandemic and its impact on our wider physical and mental health.’

We are not alone. According to Eurostat in September, 2022:

Excess mortality in the EU climbed to +16% in July 2022 from +7% in both June and May. This was the highest value on record so far in 2022, amounting to around 53 000 additional deaths in July this year compared with the monthly averages for 2016-2019.

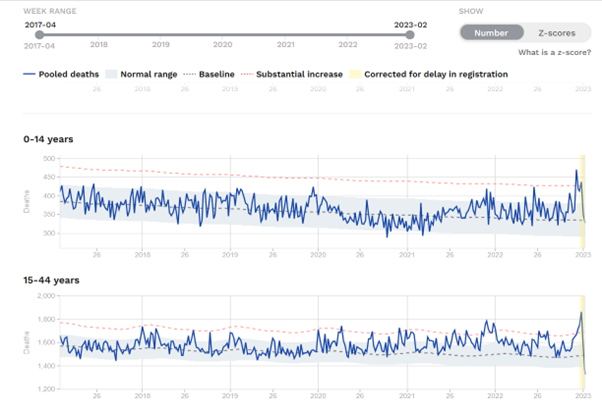

Throughout 2022, EuroMOMO pooled estimates of all-cause mortality for the participating European countries showed elevated excess mortality. Most shockingly there has been a clear uptick in deaths among young people, especially children under the age of fourteen.

Source: https://www.euromomo.eu/

Since April 2022, according to the economist Dan O’Brien, Ireland’s excess deaths have been well above the average – 15% higher than the average pre-pandemic level (circa 2,500 people over 7 months).

Most of Europe continued to record significant excess death rates up to November 2022, according to today's monthly data.

Since April, Ireland's excess deaths have been well above the average, with 15% more deaths than the pre-pandemic average (circa 2,500 people over 7 months). pic.twitter.com/fodjsKQM5i— Dan O'Brien (@danobrien20) January 17, 2023

That this unusual pattern of mortality should be occurring in the wake of a respiratory pandemic is particularly alarming, given these generate excess deaths. A wave of illness afflicting almost everybody at least once ought to have accelerated the deaths of a substantial proportion of those with underlying illnesses between 2020 (or earlier) and 2021, leaving behind a healthier population overall.

Last October, ex-Taoiseach Micheal Martin told a Fianna Fáil meeting that medical experts had warned him of ‘dramatically increasing cancers because of delayed diagnoses’ linked to the impact of COVID-19 on the health service. But we know from the UK that people missed appointments out of fear of contracting the virus, not because of insufficient capacity. Moreover, there is no evidence of an increase in mortality from cancer between 2019, 2020 and 2021.

Richard Kearney's Touch asserts the importance of physical contant in healing. Crippling anxiety in the wake of COVID-19 indicates a need for medicine to reform.https://t.co/4SLoA3YFaK@broadsheet_ie @BowesChay @indepdubnrth @corourke91 @itsmybike @NMcDevitt @iHealthReform

— CassandraVoices (@VoicesCassandra) December 1, 2021

Stress

One indicator that the stress of lockdowns and other non-pharmaceutical interventions bear primary responsibility comes from the case of Sweden, where health authorities famously took a softer approach, declining to lockdown in March, 2020. Notably, vaccination rates are above average compared to the rest of Europe.

Among a list of countries studied by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, the Scandinavian nation ranked lowest for overall cumulative excess deaths from 2020-22 at 6.8 per cent, compared to Australia (18 per cent), the UK (24.5 per cent) and the US (54.1 per cent). In Ireland and elsewhere, we may be witnessing the delayed impact of stress generated by repressive policies and fear messaging.

In his recent book, the Myth of Normal: Trauma, Illness, & Healing in a Toxic Culture (2022), Gabor Maté cites illuminating research into the biopsychosocial determinants of many illnesses, including cancer, auto-immune conditions and heart disease. ‘Stress’, he says, ‘plays its incendiary role: for example through the release of inflammatory proteins into the circulation’. This inflammation is ‘a fertilizer for the development of disease.(p.94)’

He also alerts readers to what Dr Lydia Ternoshock has described as a type C[ancer]personality. She interviewed 150 patients with melanoma and found them to be ‘excessively nice, pleasant to a fault, uncomplaining and unassertive.(p.99)’

Maté argues that ‘repression disarms one’s ability to protect oneself from stress’, explaining:

If you go through life being stressed while not knowing you are stressed, there is little you can do to protect yourself from the long-term physiological consequences.(p.100)

It is also possible that near-constant stress generated by a prevailing belief that COVID-19 was going to kill or do serious harm to you played a part in the prevalence of ‘Long Covid’.

Adam Gaffney, an assistant professor in medicine at Harvard Medical School argued for a more critical appraisal of Long Covid in 2021. Having expressed scepticism around a condition characterised by symptoms such as ‘brain fog’, he recalls being contacted by a journalist who said: ‘I’m asking as much as a person as a journalist because I’m more terrified of this syndrome than I am of death.’

Gaffney acknowledges ‘myriad long-term effects, including physical and cognitive impairments, reduced lung function, mental health problems, and poorer quality of life’ from severe bouts of COVID-19, but cites a survey showing two-thirds of ‘long haulers’ had negative coronavirus antibody tests, and another, organised by self-identifying Long Covid patients indicating around two-thirds of those surveyed who had undergone blood testing reported negative results.

He asserted: ‘it’s highly probable that some or many long-haulers who were never diagnosed using PCR testing in the acute phase and who also have negative antibody tests are “true negatives.”

In other words, Gaffney argues that for many Long Covid is a disease with a strong psychological component, which Gaffney attributes to ‘skyrocketing levels of social anguish and mental emotional distress,’ referencing a paper showing that about half of people with depression also had unexplained physical symptoms.

During COVID-19, a trusting Irish public were habituated to low intensity stress driven by constant reminders of the presence of “the virus” across media and in their day-to-day lives. Any form of rebellion against this state of affairs made one a social pariah, leading most to repress this impulse. This could have provided an ideal “fertilizer for the development of disease.”

It now appears that both lockdowns and much vaunted vaccines had only marginal effects on preventing mortality from COVID-19. It is unsurprising, therefore, that mainstream media in Ireland is giving scant attention to the collateral damage of policies that were, with few exceptions, uncritically accepted over the course of the pandemic.

Feature Image: Daniele Idini