this is tropical truth

this is celtic truth

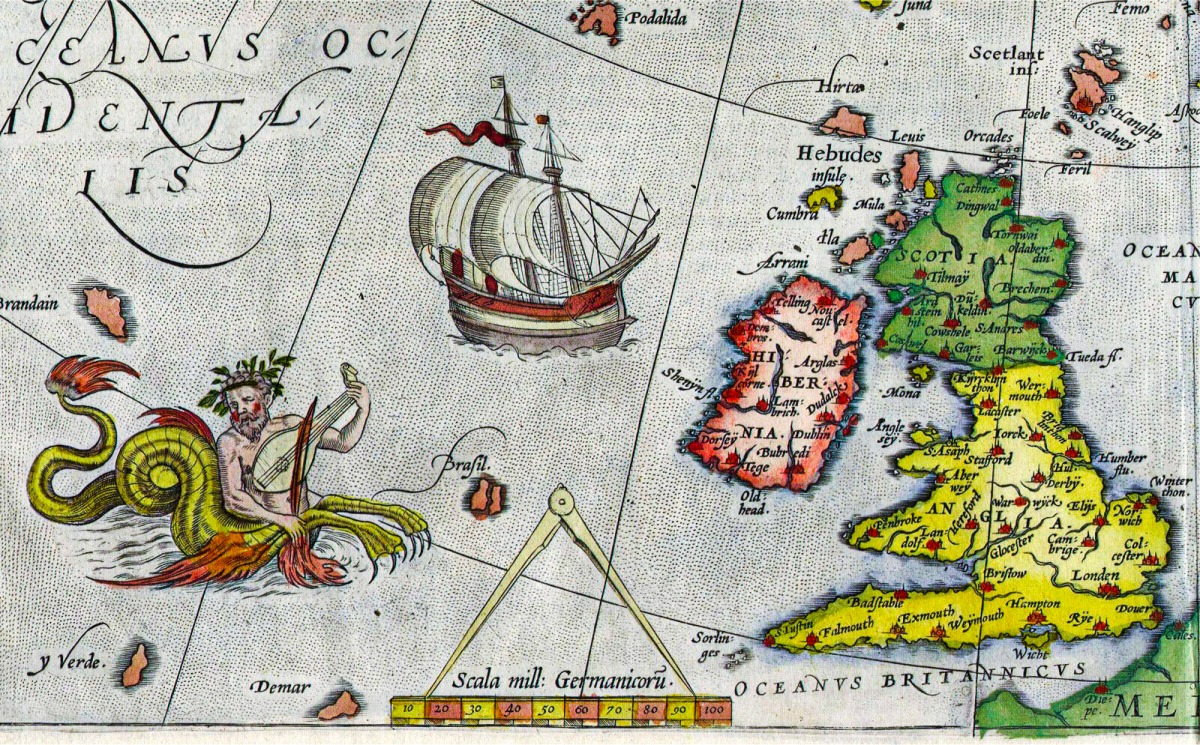

this is Hy Brasil

in the Kerribrasilian sea

for Joan, Bríd, Ezimar and Tereza

Sometimes the dead do not die. Those of us alive can fall into shadow until we learn how to listen to the voices of the dead, and the hermetic messages they transmit. The signs are here and there, although with each passing decade in this paradoxical age of amnesia, they become harder to access. Yes, it is so, the present is absent until we penetrate the absence that is present.

In 2020, I made a journey, travelling thousands of kilometres to reach the town of Iguatu in the interior of northeast Brazil, known as the sertão [a hinterland or backcountry]in the Caatinga biome. This was where I would find out more about my cousin Patrick. I arrived in Fortaleza, the capital city in the state of Ceará on 3rd February. I was still dressed in white after attending a celebration of Iemanjá, the spirit of rivers and queen of oceans, in Salvador da Bahia the previous day, which was also the birthday of James Joyce, author of the great river-book Finnegans Wake. There are no coincidences when we allow ourselves to be entangled with places, temporalities and creative practices.

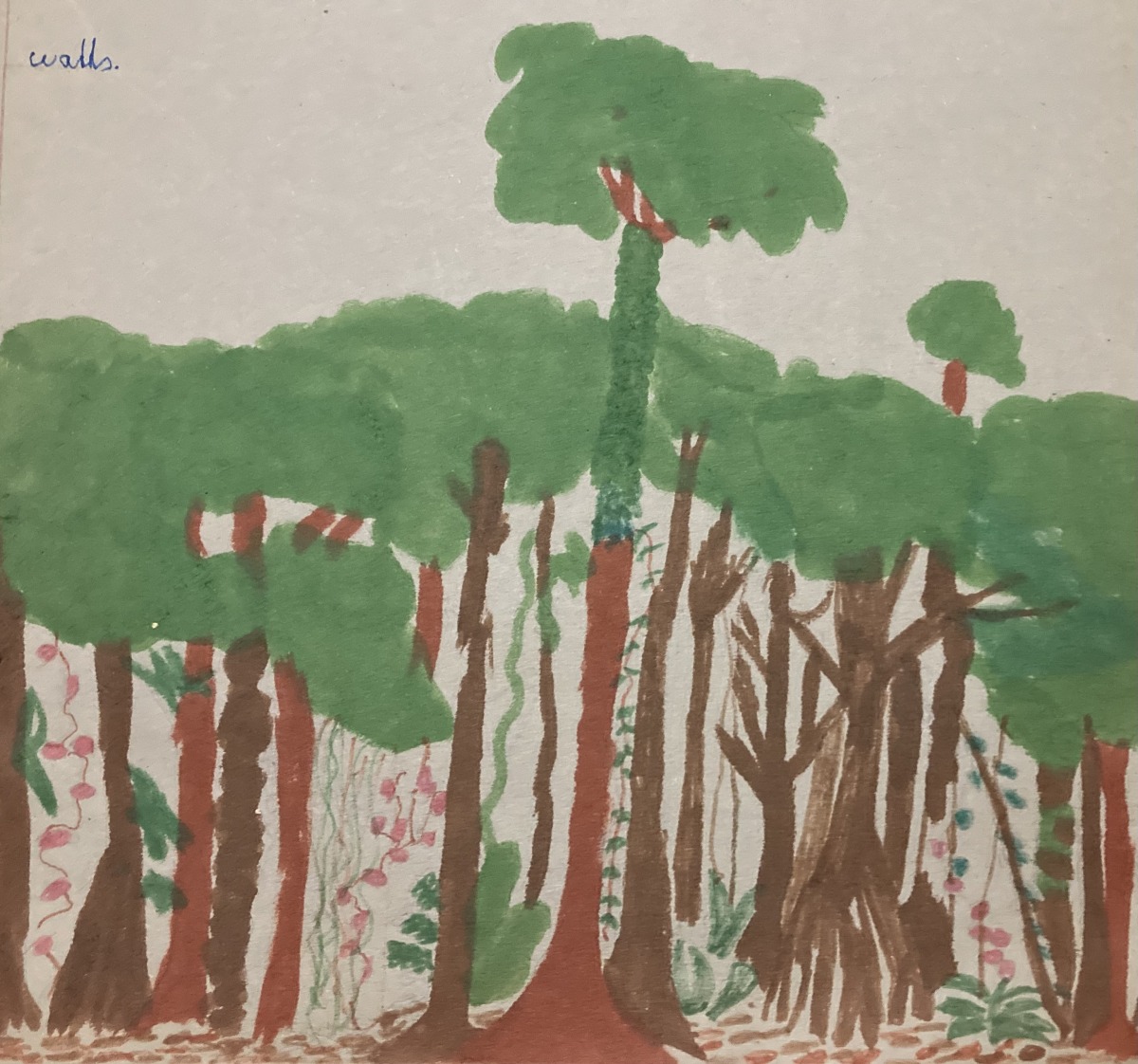

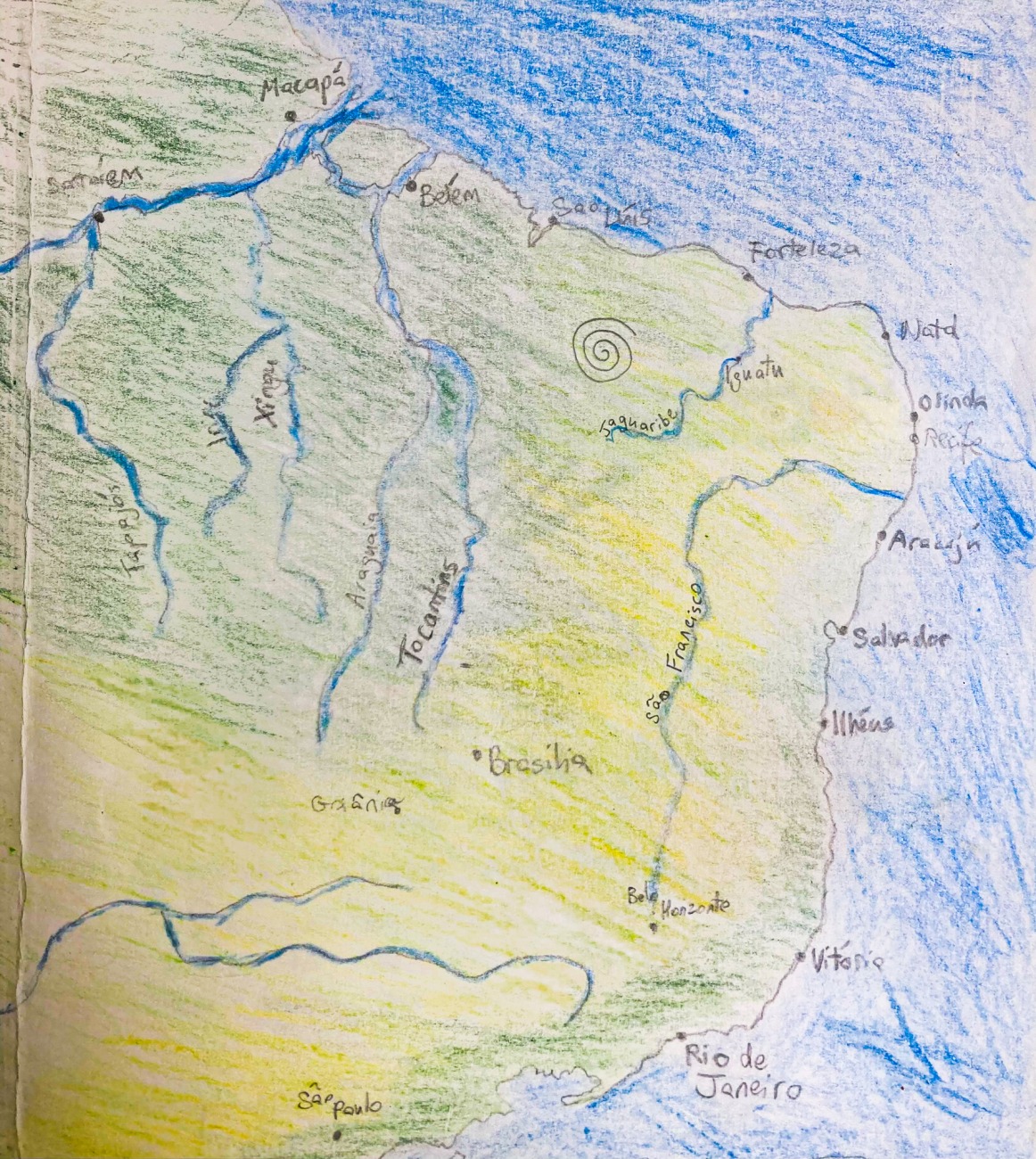

Saying aloud the word ‘Brazil’, and dreaming about what that vast land may be, has resonated in me ever since I was a boy. For my first school project at eight years of age, I decided to dedicate my time to drawing and writing about the Amazon Jungle, as my young imagination was dazzled, from afar, by the overflowing matter that all seemed so alarmingly alive. In the books I found everything seemed to be flourishing and decaying along the moving floors and rustling canopies of that great forest of the earth through which many rivers flowed.

My drawing of the Amazon jungle from a school project as an 8-year-old.

Much of the area along the enormous coastline of Brazil was once called Pindorama (‘land of the palm trees’) by the Tupi-Guarani indigenous peoples. When Portuguese navigators landed, accidentally, on the shores of Bahia in 1500, they called it Ilha da Vera Cruz (‘island of the true cross’). Today, the country is referred to as Brazil, named after a dye wood called ‘brazilwood’ or pau-brasil, which once grew in abundance along that coastline. The word ‘brasil’ probably derives from the Latin brasa which means ‘ember’ (with the suffix ‘-il’), as the wood was red like embers.

But there is another story: the name may have a connection with the lost island of Hy Brasil, which once upon a time was located off the west coast of Ireland and appeared on European Medieval and Renaissance maps.

The word probably comes from the Old Irish Uí Breasail, which means descendants (Úí) of the island (il) of beauty, worth or might (bres). With the arrival of the Age of Reason, the age of magic faded into song and oblivion and into the earth, or transferred into science, and Hy Brasil disappeared off all maps to become an obscure myth. But I follow the trail of the Portuguese poet Fernando Pessoa, who wrote: “myth is the nothing that is everything”.

Hy Brasil were on my mind when I took the seven-hour bus journey from Fortaleza to Iguatu through a prehistoric landscape of uncanny rock formations jutting out of the earth. I found out much later these were the Quixadá monoliths. My great capixaba friend Fabricio, who had roadtripped with me by land from Vitória to Salvador, called this ‘profundo Brasil’. As we got nearer to Iguatu, the landscape began to remind me of the west of Ireland. I was getting closer to the heart of the story, and to an encounter with my cousin.

The Quixadá monoliths.

‘Some Say the Devil is Dead’

Let me tell you a little of what I know of Patrick and his story, which is what stirred me to write this text. This story shows the effect the land can have on us and the effect we can have on each other. It reverberates through my own inner and outer journeys to Brazil over the years, and resonates emotionally and spiritually. This story is a way into an absence that has become vibrantly present.

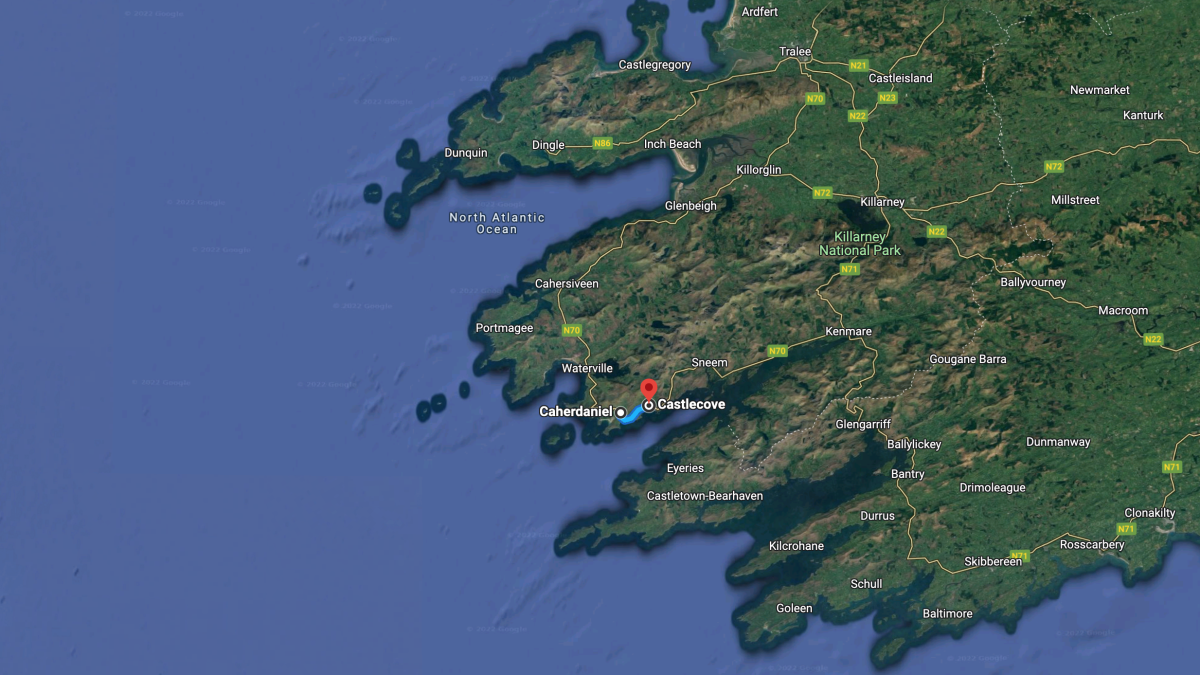

Patrick was born in Scart House in Castlecove in Kerry, on the south-west coast of Ireland. He was the son of Maurice Fitzgerald and my grandfather’s sister Lil O’Sullivan. My grandfather (my namesake), known as Batt, was born at home in Caherdaniel, six kilometres from Castlecove.

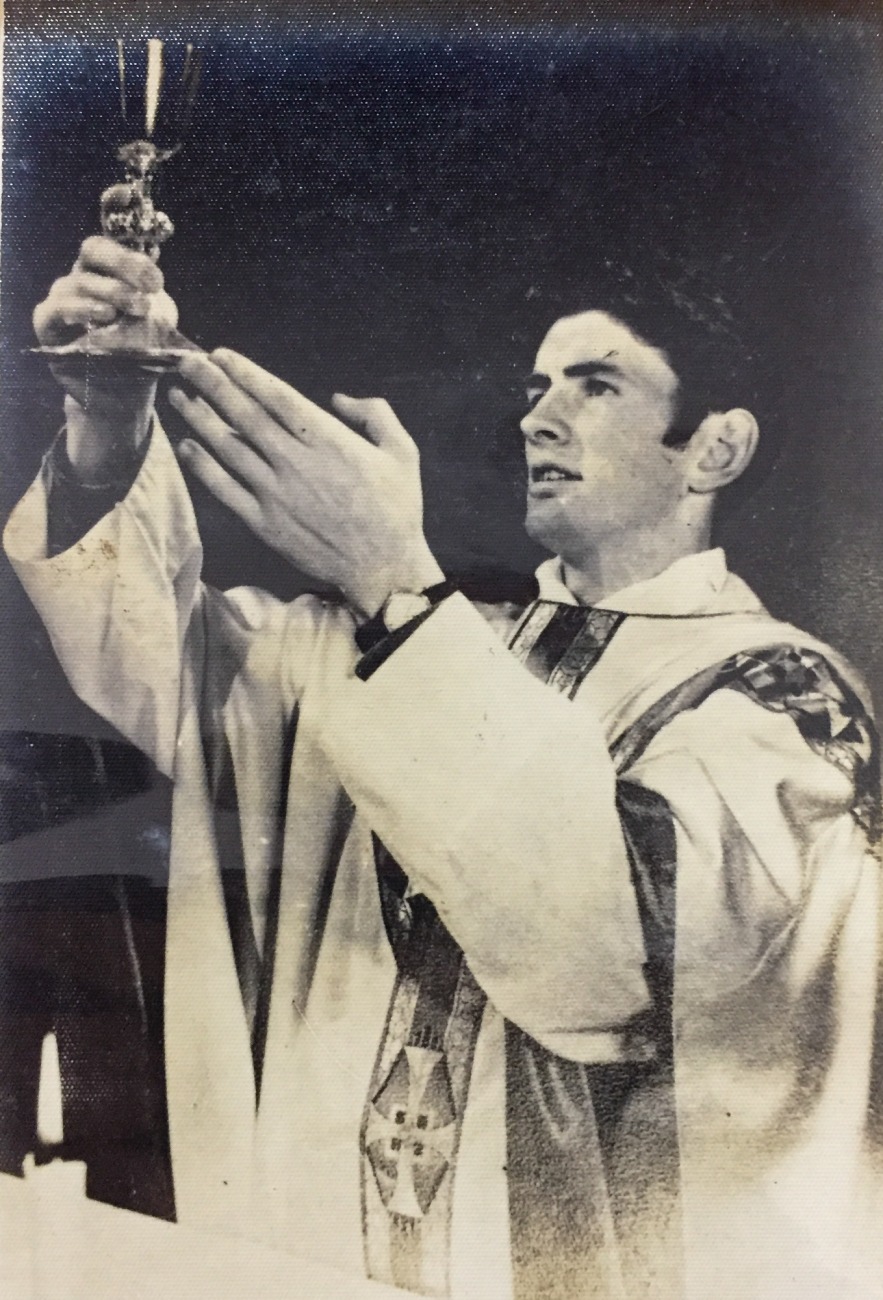

Patrick had three older sisters – Mary, Joan and Bríd. Mary, the oldest, died in 2007, and Joan and Bríd are alive and well in Kerry today. He also had two younger siblings: Maurice – born in 1949, and Eilis – born in 1951. Both died very young: Maurice in 1951 of pneumonia after a small surgery; and Eilis in 1953 of spina bifida and hydrocheplus. Born on 8th June 1945, Patrick was remembered as a joyful, gleaming boy, much loved by all, who went on to be ordained as a Redemptorist priest on 5th July 1970. Patrick left Ireland in 1972 (a year that began with Bloody Sunday and had the highest death toll of the Troubles in the north of Ireland) and arrived in Brasilia with his luggage and guitar.

Patrick’s sister Joan Rayle, in Castlecove, in front of Scart house where all the six children were born.

Brasilia had been founded twelve years previously and, like so often in Brazil, the mystical and ancient fused with extreme modernism in the new capital. Something similar can be seen in the astonishing novel by João Guimarães Rosa called Grande sertão: veredas, which was published in 1956, the same year Brasilia was proposed as the new capital by Brazil’s new president Juscelino Kubitschek. This visionary masterpiece begins with the word ‘Nonada’ [which can mean ‘into the nothing’ or ‘it is nothing’], and ends with the word ‘Travessia’ [‘crossing’ or ‘passage’], and whose protagonist’s name is ‘Riobaldo’ (literally river [Rio] deficient [baldo]. After three months in Brasilia to learn something of Brazil’s language, history and culture, Patrick was sent to Iguatu in the summer of 1972. Iguatu derives from the Tupi-Guarani words ‘ig’ or ‘i’ – meaning ‘water’; and ‘catu’ – meaning ‘good’. In a landscape so dry for much of the year, its name indicates an inviting location. It seems by all accounts that he fell in love with the place instantly. At a congregation, he said to his superior Padre José: ‘Sempre quero ficar em Iguatu’ [I always want to stay in Iguatu]. His wish would be granted.

Ireland in the 1960s and 1970s was for the most part a closed-in space. There was no electricity in parts of Kerry, and there was extremely high emigration. To suddenly be in Iguatu must have felt like being transported into another dimension. What was going through Patrick’s mind as he made his way across the Atlantic and crossed over to the Southern Hemisphere? What was it like for him taking the same journey I made through the Quixadá landscape? Such exhilaration and wonder must have filled the soul of this ebullient man. Everything around him would have seeped into his outlook and inner thoughts: the extreme weather conditions from Biblical rainfall to drought; the cacophonic sounds of all the bichos [creatures]throughout the night; the electric energies in the earth and air so close to the Equator; the rapid sunrises and sunsets; the mixed communities of indigenous peoples, Africans and Europeans. At this time, the music of bossa nova, MPB and Tropicalia, which would seduce the world, were exploding, not only down south in São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro, but also in the northeast in Bahia and Pernambuco. And the Brazilian football team, with Pelé as the poster boy, had won the World Cup in Mexico for the third time in 1970. All these elements would have dazzled any visitor.

But there was also a very disturbing current running through Brazil at the time (which continues to this day). A military dictatorship had ruled Brazil since 1964, and people opposed to the government were being tortured. There was an aggressive vision to quickly modernise Brazil, which meant cutting down the Amazon Jungle at a relentlessly accelerated rate. The population was starting to increase rapidly but lacked access to material resources, and there was a massive disparity in monetary wealth, which resulted in huge poverty across the country. This was Brazil: dance and music everywhere; a military dictatorship; mass poverty; Catholic beliefs fusing with Candomblé and Umbanda; indigenous communities (many still uncontacted) living profoundly with the land; and the beginning of the Christian evangelical movement. And then there were the distinct landscapes of the vast Amazon rainforest, the interior of the sertão regions, what remained of the Mata Atlântica, the endless coastline of golden and white sandy beaches, and the Pantanal wetlands to the west. I heard someone say that the US didn’t really have a name but it had a country while Brazil had a name but didn’t really have a country. When Tom Jobim (co-writer of ‘The Girl from Ipanema’ and one of the pioneers of bossa nova) was asked about the differences between living in New York and Rio do Janeiro, his response was: ‘Morar em Nova Iorque é bom, mas é uma merda; morar no Rio é uma merda, mas é bommmmm’ [living in New York is good, but it sucks (literally ‘it’s a shit’]; living in Rio sucks, but it’s so good].

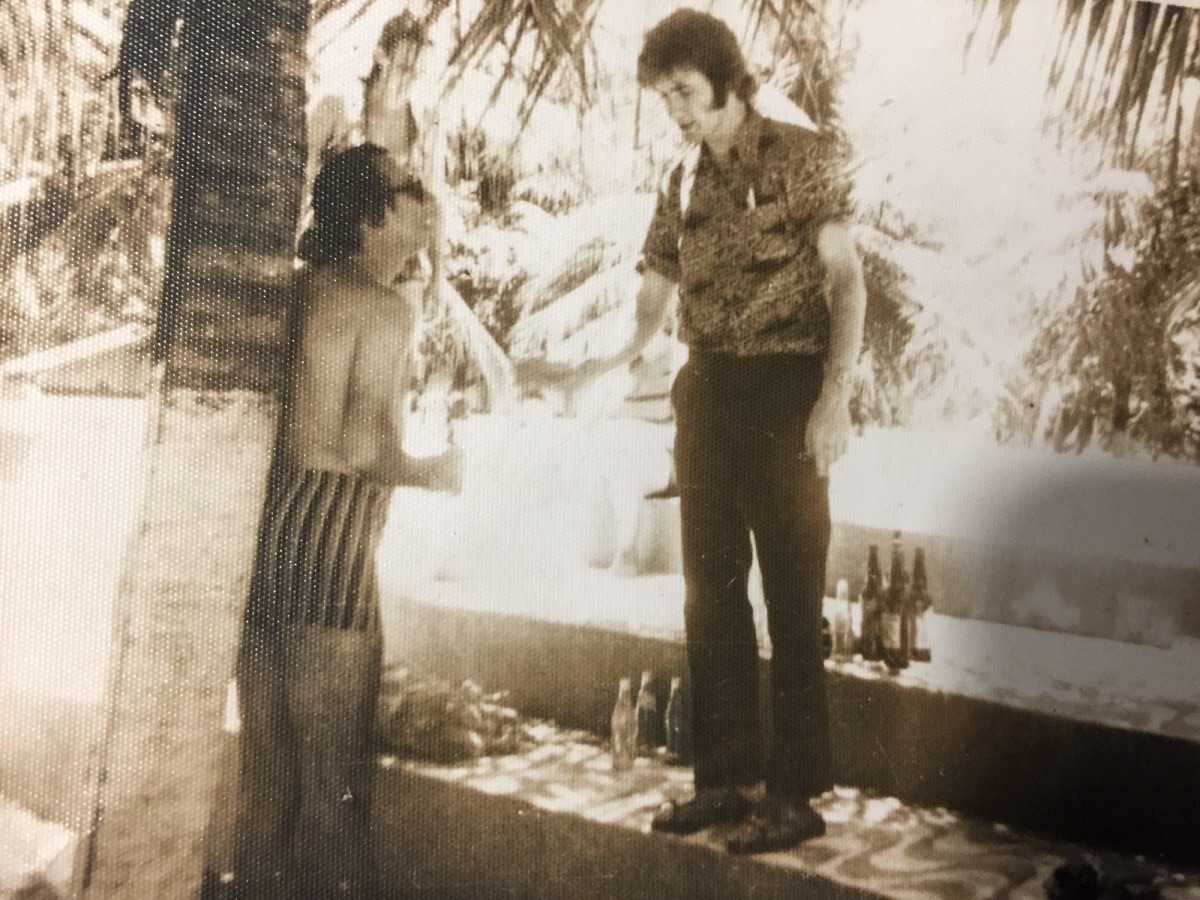

In Iguatu, the youth were immediately drawn to Patrick. He was energetic and exotic; he wore funky shirts and loved to crack jokes. He sang folk songs on his guitar. He got to know a kid who had a band and they become great buddies. Endearing himself naturally to the people and culture, he listened avidly to singers such as Dalila and Roberto Carlos (another capixaba)- known as ‘o Rei’ [the King](who has the same birthday as my brother, though he was born thirty-four years before him). Patrick was soon playing Carlos’s song ‘Jesus Cristo’, which was released in 1970, and he was always listening to another religious rock classic called ‘A Montanha’, which came out the year he arrived. Roberto Carlos was at his peak, having found God and adapting brilliantly to the grittier sound of the 70s – a perfect combination for a new generation of Brazilians.

Before visiting Iguatu, Patrick’s sister Bríd gave me the number of Father Dick Rooney, who was living in Dundalk after spending decades in the northeast of Brazil. Over the phone, Father Rooney fondly remembered Patrick and recounted how he used to be always singing an Irish folksong called ‘Some Say the Devil is Dead’ whose chorus tells of the devil supposedly buried down in Kerry, and who then rose from the dead and joined the British army. Whether unconsciously or not, I felt that Patrick had tapped into something of the soul of Brazil through this song: in the proximity of humanity with God and the devil in the land; of the displacement and mixing of influences and peoples; and of the ever-present reality of vivid death and life residing side by side.

On the afternoon of 16th April 1973, at the end of a two-day retreat with more than fifty kids from the Iguatu area, Patrick decided to take a plunge in the Jaguaribe River, which runs alongside the town. It was to be his first and last swim in the volatile river. It was the beginning of Easter Week, the day after Palm Sunday or Domingo de Ramos. His body was found by fishermen three days later further down the river. He was twenty-seven years of age.

Fourteen years later, Bríd came to Iguatu, thinking to bring his remains back to Ireland. Sister Bríd was a trained nurse and member of the Mercy Order in Trujillo and Lima in Peru from 1984 to 1990, and made the visit to Iguatu during this time, staying in the same room as Patrick. She decided that he should stay where he was in Iguatu, as that is what he had requested. Some of Patrick’s nephews and nieces also visited Iguatu later on backpacking trips.

Patrick in funky shirt standing by the river.

Amhdhorchacht

Years later, it was my turn to go to Iguatu. I also sauntered there with a guitar, and could speak Portuguese after living in Lisbon for almost a decade. A few years previously, Bríd had sent me a bunch of phone numbers for priests from the Redemptorist order out in the sertão who had known Patrick. I had gone to Brazil in 2017 with the idea that I might investigate this old family story, but after teaching for a few weeks at the federal university, I ended up following the trail of the humanitarian and Irish revolutionary Roger Casement, which took me down 3000 kilometres of the Amazon River. I only rang the numbers Sister Bríd had given me in 2019, from Lisbon, which led me to Tereza Cavalcante, the current parish secretary. She had never met Patrick, but offered to introduce me to the people in Iguatu who had known him.

My drawing of northeast Brazil. The Jaguaribe can be seen running into the sea at Fortaleza on the top right of the map.

Tereza sent a taxi driver to pick me up at Iguatu bus station and take me to the Diocesano Hotel. The taxi driver’s name was Ishmael. ‘God hears’. Nomen est omen. Every name carries a message. Call me Ishmael. The human protagonist of that great wandering American novel Moby Dick that begins with the word ‘Call’ and ends with the word ‘orphan’. Ishmael didn’t speak to me. His company and silence were calming. I said goodbye, got out of the car, and checked into the hotel. I will never forget the sounds I heard that first night. The dark damp air was emphatically awake to me, the noises and rhythms were weaving in and out of each other in call and response, sounds that I had never heard in my life. I suddenly felt the urge to say aloud a favourite Irish word – amhdhorchacht – which can be translated as raw darkness, gloaming or dusk. Although the sun sets very quickly in this part of the world, the sound and meaning of this word at that moment invoked another way of seeing and hearing. Forty-seven years after the death of Patrick, arriving and sleeping here with all those intensified sounds closing in, I felt a sort of homecoming. The spirits in the trees and in the water had heard me coming.

The next morning, Tereza picked me up and took me to the parish office in the centre of the town. Three people were waiting for me there: a young parish priest called Padre João Batista, an older priest called Mons. Queiroga, and a woman called Ezimar Araújo. Ezimar was the former secretary of the parish. She had fourteen brothers and sisters and was the daughter of Mãe dos Padres [‘mother of the priests’] (I will return to her later). She was just a few years younger than Patrick and had spent a lot of time with him during his brief time in Iguatu. She could remember so much – dates, places and what people had said. We immediately began talking in Portuguese about Patrick – or Padre Patrício, as he was known. Our mutual enthusiasm helped us understand each other despite my thick Irish-Portuguese accent and her regional Ceará accent. Ezimar and Mons. Queiroga told me stories. They talked about Patrick’s joy and youthful vigor, and how he looked like Elvis with his big mop of hair. They had lovingly kept a photo album full of black and white photographs. To me, these were precious illuminations, time-travelling portals into the past.

There was even a photograph of two of Patrick’s nieces, twins Hilda and Colette, now 56 years of age as I write these words. I had met two more of his nieces, Siobhan and Bridget, by chance on Derrynane Beach in Kerry only a few months before going to Iguatu (Patrick’s sister Joan had six children: four girls and two boys). Patrick must have travelled with this photograph, or it had been sent to him.

There was also a photo of Patrick in priestly attire, holding up the chalice:

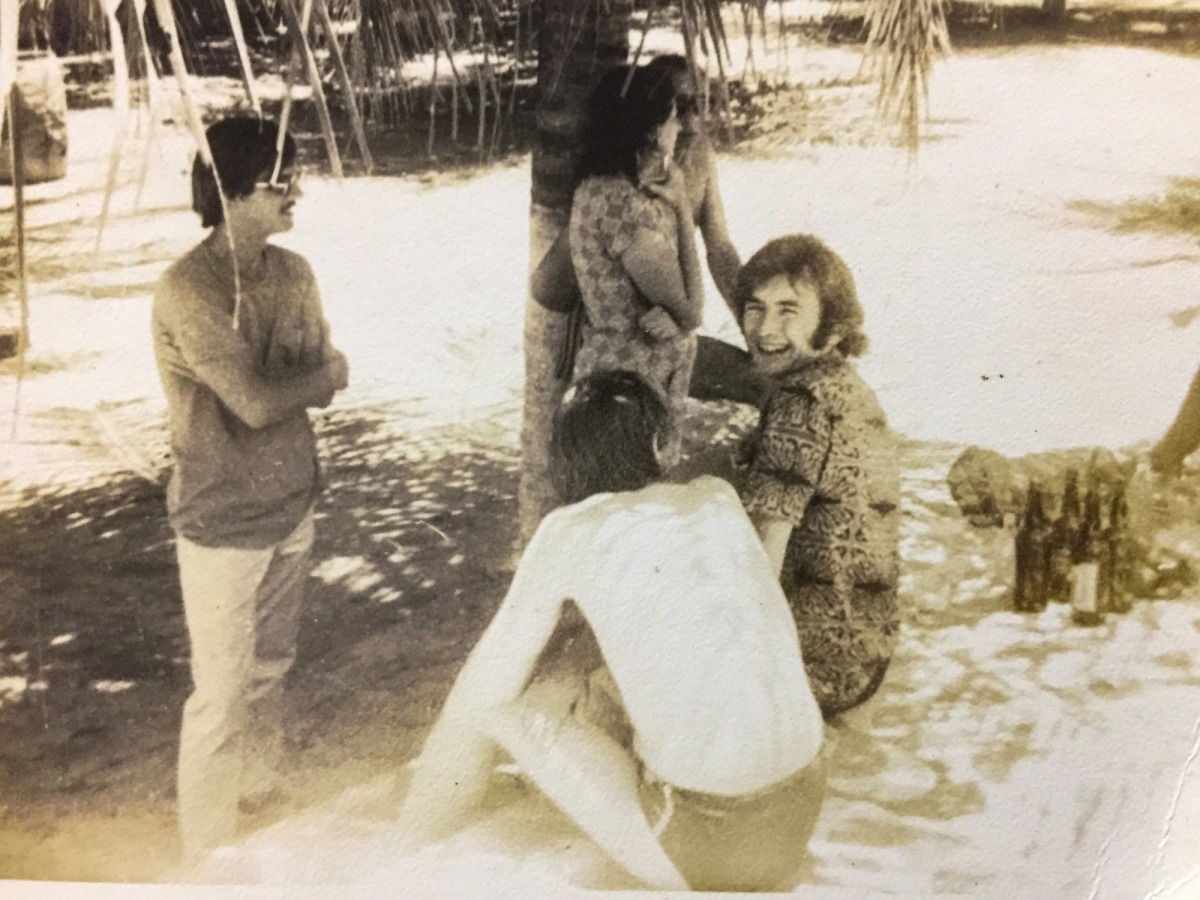

A photo of Patrick and Ezimar where they were clearly unaware they were being photographed:

And another of Patrick sitting by the Jaguaribe River with a bunch of people. Squinting and laughing heartily, he is wearing one of his colourful shirts and his sideburns are long and shaggy. He is the only one looking at the photographer.

Ezimar recalled a Christmas party that Patrick had organised in 1972. It was his first and only Christmas outside Ireland, so it must have been a big occasion for him and he obviously wanted to show his new friends in Brazil how it was celebrated back home. He decorated a tree, wrapped up presents, and sang songs. They ended up listening to Roberto Carlos for the rest of the night. Ezimar gave a big warm smile after finishing the story, and then looked at me directly as if trying to see who I really was. I saw determination and hardship in her eyes, a will to live and to give. I listened and recorded Ezimar and Mons. Queiroga. Tereza and Padre João Batista made sure we were all comfortable.

The plan was to take me to the church, Igreja Nossa Senhora do Perpétuo Socorro-Prado-Iguatu, then down to the river, but as we were leaving the parish office, I noticed Patrick’s portrait on the wall. I was stopped dead in my tracks. It was the only portrait on display, and here he was staring out at me with a good old Kerry glint in his eye. I was struck by a resemblance to my nephew Barra and for a second I saw myself in the image. It suddenly seemed very right that I was here now. Ezimar placed her hand on my shoulder. Then we left the building and walked together to the church.

There on the altar was Patrick’s gravestone for all to see. I had no idea that he would be so present. Real absence. Each step of the way on this day seemed like a natural unfolding with Patrick as our host. Ezimar, Mons. Queiroga, Tereza and I are captured in a photograph, showing us embracing, looking down at the gravestone on the altar. For a fleeting moment, I wondered whether this magnanimous memorial to Patrick was a kind of post-colonial gesture, a bowing down before a European visitor. But looking around, feeling the atmosphere, and hearing Ezimar speak, this thought quickly dissipated: I knew this was much more. It was a tragedy for the town and for Patrick; and now it was a joy and healing for Iguatu, for Patrick, and, ultimately, for me. We had crossed the Kerribrasilian sea. It was time to go down to the river.

At the gravestone on the altar. From left to right: Mons. Queiroga, Tereza, myself and Ezimar.

The Jaguaribe River is the largest dry river in Brazil. But as Patrick’s sister Joan said to me down on Derrynane Beach six months before I arrived in Iguatu: ‘there was nothing dry about it that day’. For half of the year there is no water, and then suddenly the rains come down and the river rises and rises, usually bursting its banks and flooding the town, before swerving and flowing east into the Atlantic Ocean. River of Jaguars. The word Jaguar derives from yaguara in Tupi-Guarani, meaning ‘wild beast that overcomes its prey at a bound’. But jaguars and onças have not been seen in this region for a long time.

At the river that afternoon in April 1973, along with the young kids and teenagers, there were three men, all Irish: Father Anthony Branagan (Padre Antonio), Father Michael Lavery (Padre Marcelo) and Patrick Fitzgerald (Padre Patrício). Both Anthony and Patrick went in for a swim. Some of the children were already in the water and warned them of the danger. Antony assured them that Patrick was a champion swimmer. But that was in a swimming pool. This was a river in Brazil. Minutes later he was caught in a whirlpool. Father Anthony and the children thought he was play acting as his head bobbed up and down and then down again, then up and down. Then he disappeared. The third of the three men watched helplessly from the shore.

Father Michael Lavery worked at Iguatu and then later went to work in Fortaleza. In January of this year he died in Fortaleza aged about eighty-seven. Father Anthony Branagan was in Brazil (in Ceará and then Goiás) from 1963 to 1995, and then went to work in Siberia (in the region of Kemerovo Oblast) from 1996 to 2020. With the breakout of Covid-19, he returned to Ireland to live in Clonard Monastery in Belfast. As I write, Father Anthony is eighty-eight years old. There were others who came to work in the parish during the 1970s, a generation of Irish missionary priests and volunteers. Ezimar vividly recalled more details with each passing moment I spent in her company. She told me that there was another man called Father Brendan Callanan who arrived in Iguatu a few months after Patrick’s death. They called him Padre Brandão. She said that Brandão was now living in Ireland, working in a parish somewhere but she didn’t know the name of the place. She also knew Father Dick Rooney; and there was a priest called Brian Holmes (known as Bernardo in Iguatu) who had been a close friend of Patrick’s. They had studied together back in Ireland. He is now living in Mozambique. Father Holmes, originally from Cork, was travelling from Fortaleza to Iguatu to visit Patrick on the day he died.

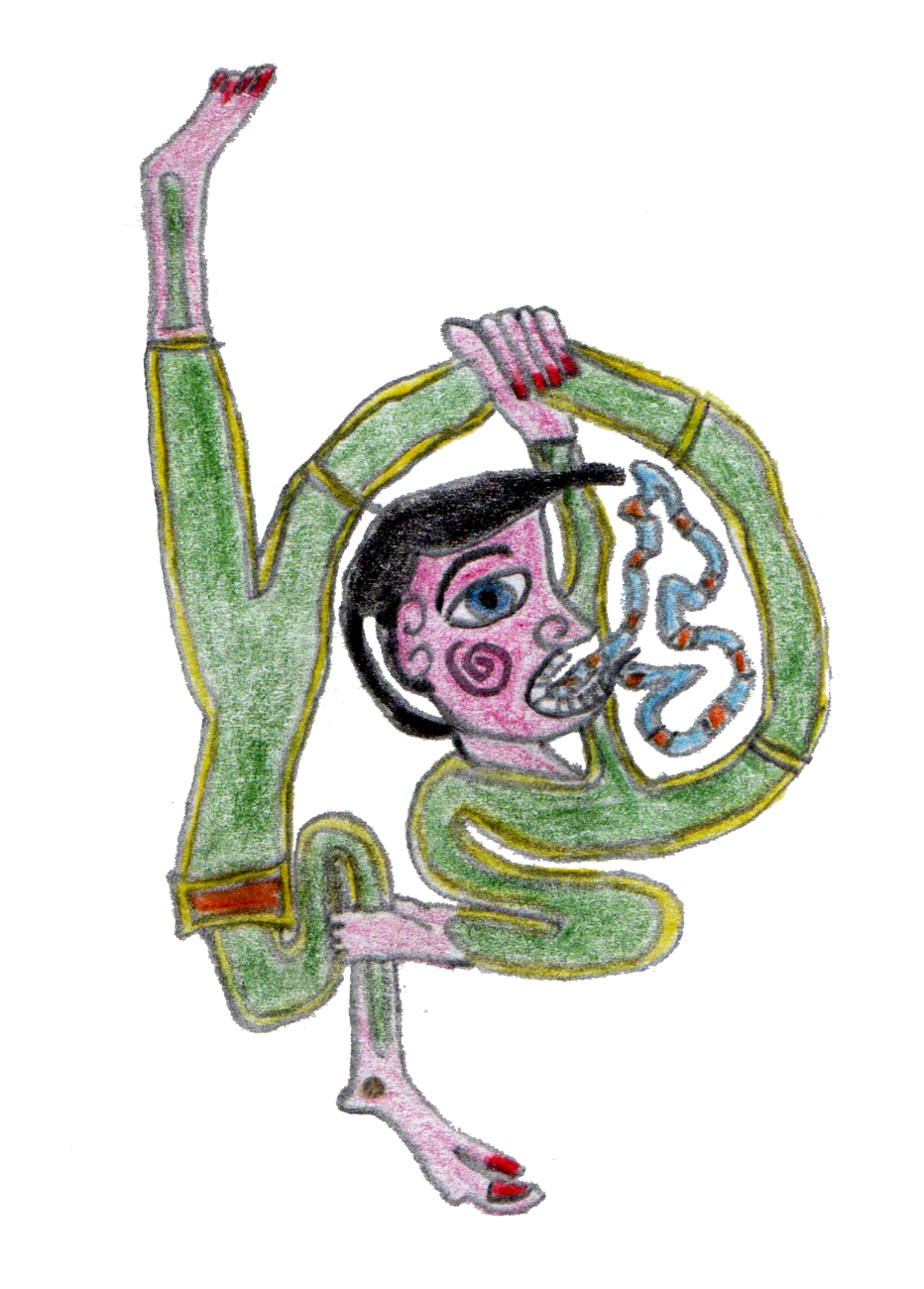

One of my drawings imitating an image from The Books of Kells, an Irish illuminated manuscript Gospel book in Latin from ca. 800 AD, now kept in the Trinity College Library in Dublin.

Four of us got into a car – Ezimar, Tereza, Mons. Queiroga and I – and we drove out of town for about ten minutes, following a road with shrubs, or mata, and buriti palm trees on either side. Raindrops began to fall for the first time in eight months. We stopped the car and walked the rest of the way along a dusty path littered with plastic waste with a rotting wooden fence on one side. Patches of mata were everywhere until we came to a wide-open treeless space where the Jaguaribe would soon be filling up again. No one spoke. I walked lightly out onto the cracked earth where Patrick had gone swimming. Each of us was in our own space, each of us dwelling on the same subject. After a while, I walked over to Ezimar. And then she broke the silence by telling me that the people of the Iguatu pray to Patrick and ask grace from him, like one does with the saints. She came close and said: ‘I pray; I ask things of him, and he intercedes. I receive my wishes in my prayers, thanks to him.’ [Eu peço; eu faço pedidos a ele, e ele intercede. Alcanço, graças por ele]. Then she said wistfully: ‘he always wanted to live here [ele queria sempre morando aqui]… He played guitar and he was happy’.

Dona Laurenise Araújo and I.

We drove back into town to visit Dona Laurenise Araújo, mother of fifteen children including Ezimar, and known in the town as Mãe dos Padres and mother of Brazil. She served me some snacks and coffee. Radiant and welcoming, with dyed purple hair, she must have been in her late eighties, and we laughed and flirted with each other. She told me that Patrick was beautiful. She was too, with her enormous hospitality, and the way she carried the weight of her ancestors with lightness and joy.

Lunch is served at the parish centre.

Then the four of us walked back to the parish office where volunteers were serving food for nearly one hundred people from the community – volunteers from the parish prepare a meal every day for those who need it. I was struck again by the kindness and tough life here. The words of the writer Jan Morris echoed in my head: ‘kindness, the ruling power of nowhere’. This is a region that has been abandoned by the Brazilian establishment, a place where liberation theology would be welcome. A proponent of this movement from Ceará, Padre Hélder Pessoa Câmara, once said: ‘When I give food to the poor, they call me a saint. When I ask why they are poor, they call me a communist.’ Here lies a deep tragedy in attitudes in Brazil and the world.

The volunteers who prepared lunch.

That night, Padre João Batista held a mass in the church. At the end of the sermon, he invited me up to the altar to face the full congregation and everyone stood up and gave a long round of applause. Later, when it was already pitch dark, I walked the quiet streets and passed by a gym filled with sweating human bodies working in motion with the exercise machines. I stared through the large window and watched. Most people were on running machines, half of them had earphones in, and some commercial pop music was blaring out into the street. I moved along. Ten minutes later, I was already at the edge of town. There were mounds of rubble and dirt on either side of the road, and only a few streetlights working. A cow was munching on the last tufts of grass available. In the middle of the dirt, there stood a sign that read “Vende-se Este Terreno” [This land is for sale] . After keeping the cow company for a few minutes, I briskly made my way back to my lodgings, longing to hear nature’s night orchestra once more. Outside my room I listened again to the sounds out there in the dark. Was that the spirit of the long gone jaguar growling into the night sky and through the trees? Calling out to me through Patrick?

“Vende-se Este Terreno” [This land is for sale]

The Retirantes – from Ceará to Curitiba to Espírito Santo

Time for one more intermezzo before I conclude this tale. It is another shock, a rupture of real absence, showing me perhaps how I was on the right caminho, beyond trained knowledge or logical articulations. As the Irish saying puts it: Éist le fuaim na habhann agus gheobhaidh tú breac [Listen to the sound of the river and you will get trout]. In 2017, I was invited to teach philosophy and literature at the federal university of Espírito Santo in the capital city Vitória by Professor Jorge Viesenteiner who was a good friend of my friend and colleague Marta in Lisbon. They had met while studying in Germany during their doctoral studies. Marta was meant to go to Vitória but she had to cancel and suggested that maybe I would like to go in her place. So off I went, landing in Brazil for the third time.

The state of Espírito Santo is wedged between Bahia to the north, Rio do Janeiro to the south, and Minas Gerais to the west. Anyone from Espírito Santo is called a capixaba. It is a Tupi-Guarani word meaning ‘cleared land for planting’ [upi caá and pixaba]. The indigenous peoples who lived in Espírito Santo called their corn and manioc plantations capixaba. The name stuck. During the time I spent in Vitória, I became good friends with Jorge. We stayed in contact afterwards and happily saw each other again in 2019 in Lisbon. When I released my solo album in March 2022, which was written in Brazil, I sent it to Jorge, and told him a little bit about the final song called ‘Iguatu’. On 12th March, I received a voice message from Jorge. He had listened to the album, and was particularly drawn to ‘Iguatu’, as his mother had been born there, which was news to me. He said he couldn’t understand some of the details and words of the song but that it moved him profoundly. He decided to share the song on his WhatsApp family group, saying it was a friend’s song about a cousin who was a priest who had drowned there. His mother – who didn’t understand any English – wrote back to say that she remembered a priest who had drowned in the river Jaguaribe a long time ago. Jorge was amazed. ‘You knew this priest?’ he asked her. ‘Of course I knew him!’ she said. ‘Padre Patrício. I worked with him in Cáritas.’

Jorge’s mother, Francisca Iranilda de Lima, was born in Iguatu in 1951 only five years after Patrick was born. She told Jorge that Patrick was young and beautiful (‘jovem e bonito’). In the voice message, I could hear Jorge laughing. His mother remembered so many details from what seemed so long ago. They had had formed a close relationship working together in the parish. She recounted to Jorge that on the day Patrick arrived in Iguatu, he was taken to the parochial centre, where a reception and lunch awaited him. Jorge’s mother and her superior Expedita Alcântara (affectionately called ‘nenzinha’) had prepared potato puré with peas and stuffed turkey, which was served with malt beer. After drinking the beer, Patrick suddenly felt very sick. It may have been an allergic reaction, and he had to be taken to hospital. Francisca Iranilda remembered that day very clearly. Jorge said that his mother began to cry softly as memories flooded back of the land she had left a long time ago. A life before another life.

At the end of 1974, Francisca Iranilda left the northeast, like so many others at that time, for the south of Brazil. Curitiba is the city that Francisca Iranilda moved to, where Jorge was born, and also where a girl I fell in love with is from; the town’s name is said to come from old Guarani ‘kur’-‘ity’-‘ba’. ‘Ty-ba’ is a suffix for ‘many’, and ‘kur y’ refers to the pine tree, which points to the large number of Araucaria brasiliensis pine trees in the region. Francisca Iranilda still has cousins in Iguatu, but the majority of her family left. They were part of the so-called Retirantes – a large movement of peoples who came down from the sertão regions because of drought, and extreme poverty. Iguatu was just another small town in the sertão, a land of forgotten people in Brazil. After teaching in Vitória, I voyaged down the Amazon River, and I came to understand why the Amazon represents the lungs of Brazil (and maybe the world). But now I understand that the sertão is the heart.

I could feel and hear in the audio message that Jorge was getting emotional. How was any of this possible? Had some strange energy called me to Espírito Santo in 2017 so we could become friends? Did Jorge know unconsciously something else was going on? To whom am I speaking? Jorge began and ended his audio message by repeating words I had said to him from the marvellous poem ‘Le souffle des ancêtres’ by Senegalese poet Birago Diop: Os mortos não morrem. Les Morts ne sont pas morts. The dead do not die.

Jaguaribe River, 5 February 2020.

Riverrun

Language is like a river: starting with a stutter, springing up, then moving under and over stones, building up speed and increasing volume, meandering and digressing, curving and slowing down, gathering and carrying dirt and grime and rubbish, becoming stagnant, getting wider, then picking up rhythm again before emptying out into the open sea. ‘The water of the face has flowed’, as Joyce writes in Finnegans Wake. Rivers and languages are states of wandering. I am a wanderer too. Iguatu – that ‘good water’ – becomes a song of call and response, where singing is existing, and where the jaguar’s breathing rises and falls in the night.

I hear the Minas Gerais poet Carlos Drummond de Andrade’s words: A ausência é um estar em mim [Absence is a presence in me].

I hear Patrick on the streets of Iguatu.

I hear him in the voices of Ezimar, Francisca Iranilda, Joan and Sister Bríd.

I hear him in the stones of the church where he is buried.

I hear him in the hum of the taxi and its drivers Ishmael and Joaquim taking me home.

I hear him in the children playing and laughing together by the dirty, dusty roadside.

I hear him in Roberto Carlos’s pop songs of salvation from 1972.

I hear him in the bichos’ sounds in the amhdhorchacht.

I hear him in the rivers, an ever-changing space of whirlpools, deep as a human soul.

Jaguaribe River, 18 March 2020 at the bottom left corner is Djalma, the sacristan of the Prado-Iguatu church.

Zagreb, October, 2022.

Many thanks to Tomica Bajsić and Croatian PEN Centre for supporting me and giving the space and time to write this text.

Listen to Bartholomew Ryan’s song: ‘Iguatu’ on bandcamp.