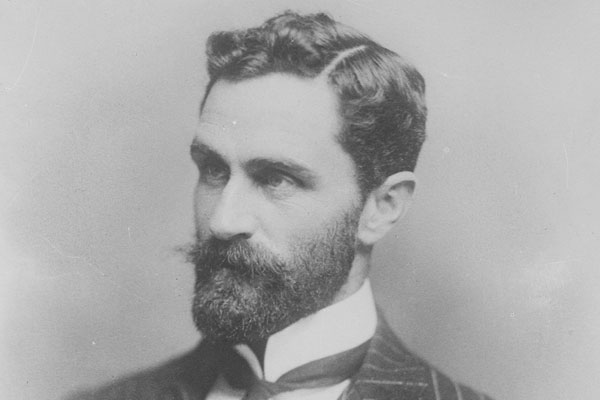

Where to begin the story of Roger Casement, humanitarian crusader, knight of the British realm, and 1916 revolutionary? Lawrence of Arabia wrote that he had ‘the appeal of a broken archangel’; Joseph Conrad said: ‘He could tell you things! Things I have tried to forget, things I never did know”; Edmund Morel described him as ‘suggestive of one who had lived in the vast open spaces’.

Casement’s life involved crisis, fissure, disintegration, newness and transformation, enduring intersections at the heart of our modernity. He is open to endless interpretation, and also – crucially – by reading and judging him we may better understand ourselves. He remains an enigma not only to others but also to himself; a complex and infinitely curious human being in troubled and confused times.

Born in Sandycove (close to where Joyce’s Ulysses begins) in Dublin in 1864, he spent much of his childhood on the coast of his beloved Antrim, Casement left for Mozambique while still in his teens, rising from a ship purser to an explorer under Henry Morten Stanley (the man who supposedly said ‘Dr. Livingston, I presume?’), and then to British consul. He was one of the central figures in exposing the genocide of millions[1] in the Congo region, then privately owned by King Leopold II of Belgium. His groundbreaking Congo Report in 1904 caused an international sensation.

Eight years on, Casement was again in the international spotlight after the release of another even more horrifying report on the brutal mistreatment, enslavement and murder of thousands along the Putumayo River[2] in the Amazon, led by the Peruvian Amazonian Company, which was registered in Britain. Both massive atrocities emerged out of the Western powers’ demand for rubber. At that time, wild rubber could only be harvested in the great jungles of the Congo and Amazon. He was knighted for his pioneering humanitarian work by the British Crown in 1913, which did not prevent him becoming a revolutionary in 1916.

The Putumayo atrocities in Peru, 1908 (photograph by Walter Hardenburg)

Casement’s journey may lie ahead of us, providing a compass to rediscover our humanity in living for the world rather than merely in it. That is why I consider him a Joycean hero. Firstly, James Joyce’s heroism is to be a radical cosmopolitan – combining the local and global – which is, for example, to be and feel Irish and simultaneously think and feel globally, and even cosmically.

A paradox central to radical cosmopolitanism is that we serve the present age by betraying it: Casement is hanged as a traitor for trying to liberate a people; Joyce is censored for endeavouring to revive a defeated people and celebrate their landscape and speech.

In 1904, when Joyce and his future wife Nora Barnacle left for Trieste, he wrote a letter to her revealing his vocation: ‘I cannot enter the social order except as a vagabond.’ For Joyce and Casement, to be a radical cosmopolitan is to be an exile soul – ‘self exiled in upon his ego’ as Joyce put it in Finnegans Wake – perpetually on a homeward journey. Thus, while every page of Ulysses is rooted in a specific place in Dublin, it is also what Yuri Slezkine called, ‘the Bible of universal homelessness’.

II

To be a Joycean hero is, secondly, to be driven by love – love for all living creatures, defined by a courage to oppose oppressive political systems; listening to an inner voice reminding us of our core values, shutting out belittling and paralysing chatter. The one time Leopold Bloom really sticks up for himself in Ulysses is in the Cyclops episode, when faced with patriotic bigotry and racism. He declares that true life is love. It is no coincidence that the only mention of Casement in Ulysses is in this same episode, as one who stood up for the indigenous peoples of the Congo and Amazon:

—Well, says J. J., if they’re any worse than those Belgians in the Congo Free State they must be bad. Did you read that report by a man what’s this his name is?

—Casement, says the citizen. He’s an Irishman.

—Yes, that’s the man, says J. J. Raping the women and girls and flogging the natives on the belly to squeeze all the red rubber they can out of them.

Ulysses is set on a single day – the 16th June 1904 – itself a symbol of love for Joyce as this was his first official romantic encounter with Nora Barnacle. As the patriarchal, colonial powers of Britain, France, Germany and Russia locked horns in a horrific world war, sending millions of young men to needless slaughter, Joyce wrote his masterpiece of ineluctable love – embodying truth, beauty and freedom.

‘I cannot enter the social order except as a vagabond.’ – James Joyce, 1904

Love incorporates both sundering and reconciliation, and remains a consciously unstable force in Joyce’s work. It resides ‘ineluctably constructed upon the incertitude of the void’ – a sentence from the penultimate episode of Ulysses, which could serve as Joyce’s definition for art, beauty and human existence.

‘… and finally when up in those lonely Congo forests where I found Leopold I found also myself – the incorrigible Irishman – I realised then that I was looking at this tragedy with the eyes of another race’ – Roger Casement, 1907

Casement’s affirmation of life drove his love for the marginalised populace of an unprotected wilderness. Like Joyce, who wrote in the language of the coloniser on behalf of both the colonised and coloniser, Casement recognised the tensions between coloniser and colonised. He concluded a letter to his friend William Cadbury in 1911 with these words: ‘PS. If I wrote a history of the slavery I’d be kicked out of the public service.’

III

Thirdly, a Joycean hero acknowledges the ‘epic of the human body’ – Joyce’s description for Ulysses. With nations and empires obsessing about war, obliterating the body and any hint of joyful sensuousness, Joyce and Casement’s war is an affirmation of the body, a resounding ‘Yes’ to life that is the last word of Ulysses.

Joyce’s solitary writing of Ulysses, with each episode representing an organ of the body during the life-negating years of World War I, and Casement’s tireless campaign for the voiceless oppressed in the Congo, Amazon and Ireland – along with his anti-colonial and anti-war essays collected under the title The Crime Against Europe – represent a grand defiance and affirmation of the human spirit.

Casement can be found buried deep in the fourth and final section of the second part of the four books that make up Finnegans Wake set in the ocean off the coast of Ireland, on embarking and disembarking: ‘… and after that then there was the official landing of Lady Jales Casemate…’ There is allusion here to both Casement and checkmate (‘Casemate’), jale (to work) and jail (prison). The Lady can imply Britannia a symbol of the British Empire, and equally can allude to an idea of a crossdresser or homosexual – also echoing the description of Bloom as the ‘new womanly man’ in the hallucinatory ‘nighttime’ episode of Circe in Ulysses.

To Bloom’s ‘new womanly man’ and Protestant Jew subjected to racism and betrayal, Casement is a sensitive homosexual, who was also well positioned to understand deeply the oppression and silencing of the marginalised. As the mischievous, plural voice will say to the reader in the middle of Finnegans Wake, “do you hear what I am seeing?”

IV

Fourthly, the Joycean hero embodies the antinomies and conflicting identities of the human self, such that Casement is, what Joyce calls in Finnegans Wake, “two thinks at a time” and “twosome twiminds” – as Protestant/Catholic, British consul/Irish revolutionary, Christian/homosexual, and traitor/humanitarian. The “twosome twimind” is key to understanding Joyce’s thought and vision – seen in words such as ‘chaosmos’, ‘thisorder’ and ‘jewgreek’. The conflicted, dissolving, plural hero reveals the cracks and anxieties of his age – with Ireland a site of contradictions culminating in a bitter civil war (1922-23).

The phrase “twosome twiminds” comes from the chapter on Shem Skrivenitch – Joyce’s thinly disguised self-portrait – in Finnegans Wake:

[…] a nogger among the blankards of this dastard century, you have become of twosome twiminds forenenst gods, hidden and discovered, nay, condemned fool, anarch, egoarch, hiersiarch, you have reared your disunited kingdom on the vacuum of your own most intensely doubtful soul.

I attempt a translation of this passage, alluding to our unconscious designs:

a nigger among the white bastards of this dastard century, someone who has developed a dual or conflicting mind, going against the gods, condemned and foolish, containing elements of the archetype of the anarchist, egoist and heretic, and raising up your disunited kingdom upon the void of your own most doubtful or despairing soul.

This could be an illuminating description for Casement as well as Joyce, who both performed the role of outsider. Each employed the term ‘the language of the outlaw’, and Joyce’s use of the word ‘nogger’, alluding to the offensive word ‘nigger’, is used in an opposition he shares with Casement to the colonial master. These controversial and conflicted figures – each one simultaneously magnanimous and egotistical – intertwined as servants and traitors of the ‘disunited kingdom’ (Ireland and/or the United Kingdom).

In dueling opposites, Casement is a powerful example of combining the realist and the romantic: as one who casts a suspicious eye over human systems in his clear, jargon-free, reports on Congo and Putumayo. He was among those dangerous dreamers, living a mythic life of complexities and great challenges, a mediocre poet whose life became an epic poem.

The Amazon River in 2017 (photograph by Bartholomew Ryan)

V

Finally, the Joycean hero’s journey is one of transformation. Casement became an orphan at the age of thirteen and then spent twenty years in Africa and seven years in Brazil. He embarked on a transformative journey from advocate of British colonial rule to humanitarian crusader and anti-imperialist.

If we observe the stylistic differences between Casement’s diaries from the Congo and those from the Amazon it is as if each has been written by a different man. The cryptic statements, short-hand daily reminders and mini weather reports in the Congo diaries give way to the sprawling, dense, meandering Amazon journals, opening out like the great river itself.

It is no accident that Casement loved and collected butterflies – the epitome of transformation. Transformation is deeply ecological. Casement was acutely sensitive to his environment. As he moved up river he was surrounded by the vegetation of the two largest jungles of the world. In his journals we find the eye of an ethnographer and environmentalist, who understands the intimate connection between any land and the people living there.

This frontier environment at the limits of human endurance raises his awareness of the truly global struggle he was involved in. In a letter from Brazil after publishing the Congo Report, he wrote that it was deep ‘in the ‘lonely Congo forests’ where he found King Leopold II, who directed the enslavement of the country, along with himself – ‘the incorrigible Irishman’. The rivers and trees of the two mightiest jungles on Earth lead Casement to places few are willing to travel.

The James Joyce Bridge over the River Liffey in Dublin today.

Finnegans Wake may be viewed one day as the great novel of ecological thought, a theme hinted at in Ulysses. This is apparent on every page of his last work as words mutate in each sentence to become living, breathing entities, and as all things, animate and inanimate, metamorphise. Ultimately in this extravaganza of ecological vision, the river is crucial to emptying out, recycling and renewing. Hundred of rivers from all over the world are woven through the famous chapter involving the two washerwomen gossiping about Anna Livia Plurabelle on the bank of Dublin’s River Liffey (whom she is); the first word used in the book is ‘riverrun’; and Joyce’s final soliloquy is delivered by Anna Livia Plurabelle – meaning the plural, beautiful, river of life. The rivers and the trees are the site for transformation, creativity and redemption for Casement, Joyce and humanity.

Bartholomew Ryan co-wrote (with Christabelle Peters) and performed a two-act monologue play on Roger Casement in Lisbon, Strasbourg and Bergen in 2016. He is a philosophy research coordinator at the New University of Lisbon (http://www.ifilnova.pt/pages/bartholomew-ryan) and leader of the international band The Loafing Heroes (https://theloafingheroes.bandcamp.com/)

Featured Image: Daniele Idini

[1] See Hochschild, Adam; King Leopold’s Ghost: A Story of Greed, Terror, and Heroism in Colonial Africa, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1999.

[2] See Goodman, Jordan; The Devil and Mr. Casement: One Man’s Battle for Human Rights in South America’s Heart of Darkness. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2010