The attention in W. G. Sebald’s writing to the fascist era in European history anticipates many of the controlling measures of our time. Images abound throughout his work, leading to observations and recollections both of historical incidents, literary tradition and the lives of friends and immigrants, as well digressions on nature. We find a unique blend of memoir, historical and philosophical disquisitions, and a form of narrative storytelling based on fact with the occasional intrusion of fiction.

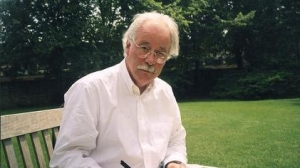

W.G. Sebald

Sebald’s oeuvre represents a novel semi-fictional genre with precedents in Nabokov’s Speak Memory (1951). In effect, he subverts fiction and its use of metaphor. He may be considered British in the sense that every European émigré from Otto Khan Freund to Sigmund Freud has been, and the speckled observations of an outsider about a new homeland permeate the texts.

A professor of literature for many years in East Anglia University, Sebald died in a car crash following a brain aneurism. This ended a meteoric rise, and thwarted the possibility of a Nobel Prize for Literature. Albert Camus at least lived to receive the accolade before dying in similar circumstances.

At many levels, Sebald’s books display a sense of impending mortality and certainly schadenfreude. He invokes a feeling of being among the last of the U.K. émigré intellectuals of cosmopolitan sophistication, and his work merits inclusion in the great Middle European intellectual canon of Franz Kafka, Joseph Roth and Stefan Zweig, among others. There is an abundance of cultural references that recalls this heritage.

There is also an unmistakable Proustian feel to the descriptions, though oddly that author is never expressly invoked in what is Sebald’s factual narrative of ideas, or of images which play with memory though reflections distinct from Proust’s technique. Thus, we find no attention to high society, or social politics and love affairs, as much as memories of dislocation, a recurring outrage at man’s inhumanity towards his fellow man, and an acute sense of transience and fungibility.

The Rings of Saturn

The Rings of Saturn (1995) is the most obvious example of an exhumation of the European intellectual tradition. It begins with an admission that this is a reconstruction of notes a year after a hospital admission.

An evocation of Rembrandt’s painting ‘The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp’ (1632) suggests more than a brief flirtation with the possibility of his death. He also compares himself to Grigor in Kafka’s Metamorphosis, when he awakens as powerless as a slug, and indeed Kafka is omnipresent throughout his work.

Rembrandt’s ‘The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp’

Visits to the most mundane of buildings or scenery stoke foreboding and evanescence. In a striking passages he visits the British coastline, where he equates declining fish stocks with human destruction and desecration in Belsen. It is a shocking juxtaposition of ecocide with murder and genocide, especially the Shoah or Holocaust, which also pervades this work, and indeed is all-pervasive as a backdrop or synonym.

The great Irish humanitarian revolutionary Roger Casement features heavily in The Rings of Saturn (1995), with the inherent contradictions in his life – receiving a knighthood prior to negotiating with the Kaiser during World War I – examined thoroughly. Casement’s gun running led to a show trial culminating in his execution, a scene masterfully conveyed in Sir John Lavery’s painting ‘High Treason: The Appeal of Roger Casement’ that hangs in the King’s Inns in Dublin where I lectured for many years. It is a sage warning that sympathy with the oppressed rarely, if ever, coincides with the interests of the establishment.

High Treason: The Appeal of Roger Casement by Sir John Lavery.

Vertigo

Vertigo, (1990) is another non-novel featuring a trip to mainland Europe. It succeeds in stirring the same reflections on human infamy and cruelty as in his other work. This includes a disquisition on the incarceration of Casanova by the authorities for vice. Vertigo represents a grand tour through historical sites, with attendant horrors recollected, and brought into a contemporary frame.

Italy is a prevalent and semi-fictional narrative chapter where we meet Kafka’s Dr K, before proceeding through personal narratives on friends and relatives disappeared, or driven mad or suicidal, with linkages to landscape and cultural artifacts. Here, we seem to be witnessing the unravelling of the immigrant through displacement.

The book concludes in England with a vertiginous dream of environmental destruction influenced by a passage from Samuel Pepys – a description of the Great Fire of London of 1666.

It occurs to me that it is exactly the sort of book that fascist authorities, presently resurfacing throughout Europe, would ban or burn. Or perhaps it is more likely to be the victim of a broader loss of historical memory, best described as a social media auto-da-fé.

The Great Fire of London, depicted by an unknown painter (1675).

Other Works

The Emigrants (1992) is a story of dislocation obviously personal, but using the lives of others to show how awfully sad immigrant experiences can be. Suicides are much in evidence along with mental institutions. Cultural adaptation is always difficult for the emigrant.

Furthermore, the grim industrial buildings of the North of England are wonderfully evoked in an analysis of the life and work patterns of the artist Herbert Ferber, who he met many times in Manchester.

The book concludes with images of Jewish graves and a fascinating codicil on how even the ghettos maintained an appearance of normalcy, with functioning post offices and judicial systems, throughout the carnage of the war.

The most famous and lyrical of his books is Austerlitz (2001), stemming from an apparently fictional conversation with a gentleman of that name in Belgium. Among his works, it is the one that most resembles a conventional novel.

The oeuvres is virtually unclassifiable, albeit threading through it we find a transplanted and expatriated lens on a European history of cruelty, barbarism and murder – also evoked in Francisco Goya’s black paintings.

Goya’s (La romería de San Isidro), A Pilgrimage to San Isidro, 1819–1823.

Through the endurance of his writing, as the perpetual outsider, Sebald operates from outside time to provides a distinct perspective on what is happening in our present age.

In a clairvoyant way Sebald’s books anticipate the revived relevance of the Holocaust, and spotlights the immigrant experience, while emphasising the importance of civility and culture. He also presage an impending environmental collapse.

One of the last of the great European intellectuals seems to have anticipated what we are seeing in this period of greatly diminished civil and human rights; yet at a certain level he was merely asking us to remember, in a culture of casual forgetfulness.

Feature Image: The Liberation of Bergen-belsen Concentration Camp, April 1945 Overview of Camp No 1.