Over the course of 2019 there has been a sharp increase in deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon rainforest. Human rights violations and ecological decimation in the region are more of a concern than ever under President Jair Bolsonaro, the so-called ‘Trump of the Tropics.’ Brazilian activist and humanitarian Bruna Kadletz calls on the international community to act in protection of the forest, before it´s too late.

The Amazon is burning

The pain of our beloved rainforest

burning in flames is our pain

It is the pain of all living creatures

The Amazon is burning through the criminal hands

Of agribusiness and our politicians

I first heard of Roger Casement on a visit to the Amazon region in 2017, when Alan Gilsenan, the Irish filmmaker who wrote and directed ‘The Ghost of Roger Casement’ (2002), told me about the Irish-born British diplomat’s journey into the rainforest at the beginning of the last century.

It was only, however, in the evening of August 18th 2019, during a film festival featuring Casement´s documentary in São Paulo, Brazil that I fully grasped his importance. Particularly at this time, when human rights violations and ecological decimation in the Amazon region are more concerning than ever.

Casement´s humanitarian efforts had gained him international recognition by 1904, when he reported on the torture and enslavement of indigenous peoples during the rubber boom in Congo under King Leopold.

In 1910 the British government sent him to the Amazon rainforest to investigate similar violations in the region of the river Putumayo, Colombia. There he described mutilation, rape, torture and exploitation, carried out under the rule of Julio César Arana, a Peruvian entrepreneur and politician. He also provided humanising narratives for the Putumayo people, emphasising their beauty and bravery.

Up to this day the indigenous people of Putumayo revere Roger Casement. In one part of the documentary an elder connected the survival of his people to the diplomat, adding that the Amazon needs another Casement to save the forest, and its people, from modern forms of exploitation.

I fell sleep inspired by Casement’s bravery and humanitarian commitment to bring an end to oppression, imperialism and violence against indigenous peoples.

On the following day, August 19th, a blanket of smoke cast a dark shadow over São Paulo. By 3pm the day had turned into night. Black, low-level clouds swallowed up the largest city in South America. The overcast winter afternoon had been caused by wildfires raging thousands of kilometres away. In Northern Brazil the rainforest had been burning for weeks, as wildfires passed through the states of Acre, Rondônia, Mato Grosso and Mato Grosso do Sul, reaching the border with Bolivia and Paraguay. The smoke travelled with the wind from north to southeast Brazil, darkening that São Paulo afternoon.

This corridor of fumes was also a symbolic reminder of the dark atmosphere pervading Brazilian politics, society and wider environment.

Far-right President Jair Bolsonaro, along with Environmental Minister Ricardo Salles and other supporters, must be held accountable for policies which have brought about this destruction. Prioritising the interests of agribusiness and the extractive sector has caused huge damage to invaluable ecosystems and suffering to native peoples.

Bolsonaro´s agenda has been catastrophic for Brazilians and the world. Now it is time for the international community to wake up. Individuals can exert pressure on national governments, leading to economic sanctions against the regime.

Image © Bruna KadletzThe Brazilian National Institute of Space Research (INPE) reports that so far in 2019 the country has experienced the highest incidence of wildfires in five years, registering 74,155 outbreaks between January 1st – the date Bolsonaro came to power – and August 20th. This figure represents an increase of 85% compared to the same period in 2018.

Data collected by the Institute of Environmental Research in Amazonia (IPAM) links the fires to deforestation, which is not solely explained by a period of drought. IPAM discovered that the ten Amazonian municipalities with the highest number of fires are also the ones with the highest deforestation incidences this year.

At the beginning of August, encouraged by Bolsonaro´s discourse, farmers in Pará state declared a ‘day of fire’, when several sites in the state were set alight. On August 10th, authorities registered 124 outbreaks in Novo Progresso, 194 in Altamira – followed by more than 237 the following day.

These criminal acts clear the land in preparation for cattle ranching or growing crops, including genetically modified soybeans, maize and canola that are imported all over the world, generally as animal feed rather than for direct human consumption.

Last July Ricardo Magnus Galvão, then director of INPE, attracted the attention of Brazilian and international media when he defied the president by revealing the extent of deforestation under Bolsonaro´s administration. The President dismissed scientific facts and attempted to discredit INPE´s data in a failed attempt to mask the rainforest’s grim fate. In exchange for exposing the truth Galvão was removed from his post.

The Amazon is burning and dying a painful death, while Brazilian agribusiness celebrates governmental permits to deforest and exploit the rainforest. In Tocatins, a state located in the heart of the Amazon region, within a single day of August the government issued 557 authorisations to deforest specific areas of the state – all aimed at exploiting the land for agriculture.

Altamira, in the state of Pará, registered the worst concentration of deforestation in Brazil. Between 2013 and 2018 the municipality had seen clearances of 1.9 thousand square kilometres of rainforest. In 2017 I visited Altamira, including the area where the controversial Belo Monte Hydroelectric Complex was built.

To clear space for the canal, diverting water from the Xingu River to the dam, Belo Monte construction had cut down large stretches of the rainforest. Along the route to an indigenous village deep inside the jungle, we drove by what seemed a graveyard of trees. Tens of thousands of massive tree trunks laying silent on the ground told a vivid story.

The municipality illustrates another alarming link – the relationship between deforestation, natural resources exploitation and violence towards human beings. Altamira is the second most dangerous city in Brazil, with one-hundred-and-thirty-three recorded homicides for each one hundred thousand inhabitants. Thus, according to Daniel Cerqueira, coordinator of the organization Violence Atlas: ‘The cities with the highest deforestation rates are the ones with the highest numbers of homicides.’

In the years I lived in Maranhão in legal Amazonia, I witnessed aspects of this dark reality. Most of the numerous occurrences of illegal logging in protected areas were closely associated with violence against indigenous people.

Like many Brazilians I feel a mixture of despair, powerlessness and sadness over the direction our country and political system has taken. It is painful to watch what is happening, and even more so to realise this is only the beginning in an era marked by climate breakdown, ecological decimation and societal collapse.

As the elder of the Putumayo indigenous people stated in ‘The Ghost of Roger Casement’, we are in urgent need of a contemporary version of Roger Casement to denounce the atrocities, human rights violations and ecocide, especially in Brazil. And, more importantly, to bring about a shift in consciousness. But will politicians and world leaders listen to the pain and suffering of Pachamana and those fighting for her survival, for all our survival?

We must preserve hope, even in these dark times. I am constantly searching for motivation to confront how everything seems to be falling apart, and when my greatest source of inspiration is burning down.

Roger Casement inspired me to delve deeply inside myself in order to find the courage to walk straight into the heart of suffering, shed light on human rights violations and ecological devastation, and help instigate transformation.

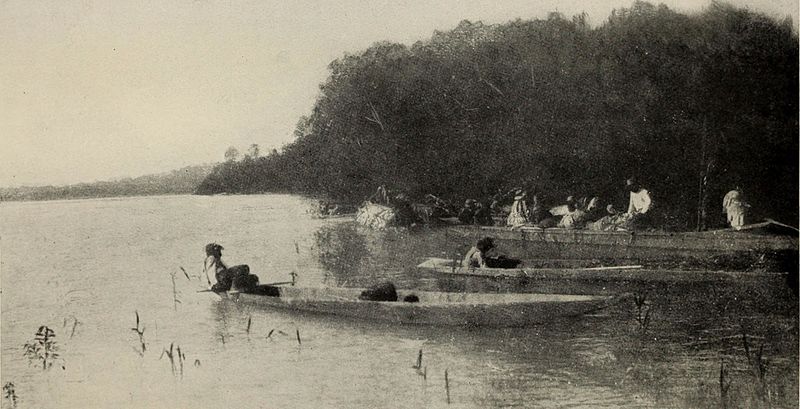

Featured Image is of Roger Casement among the Putumayo people c.1913.

If you enjoyed this article you might consider purchasing our new hard copy Cassandra Voices II.

Become a part of the Cassandra Voices community through a monthly donation on Patreon.