Before Ireland’s third pandemic lockdown began, in December 2020, I paid a visit to my local library, in the hope of stocking up on books and films to sustain me in the months ahead. And I’m glad I did: the long weeks of isolation would have been far heavier, more dispiriting and lonely, without the hoard of soul-food I gathered from the library’s gloriously ample and eclectic store.

Among the titles which have so enriched my days since, was a retrospective collection of work by the indigenous Peruvian photographer, Martín Chambi, born (to my rather boyish delight, exactly a hundred years before myself) in 1891. I can say without exaggeration that it’s become one of my favourite books.

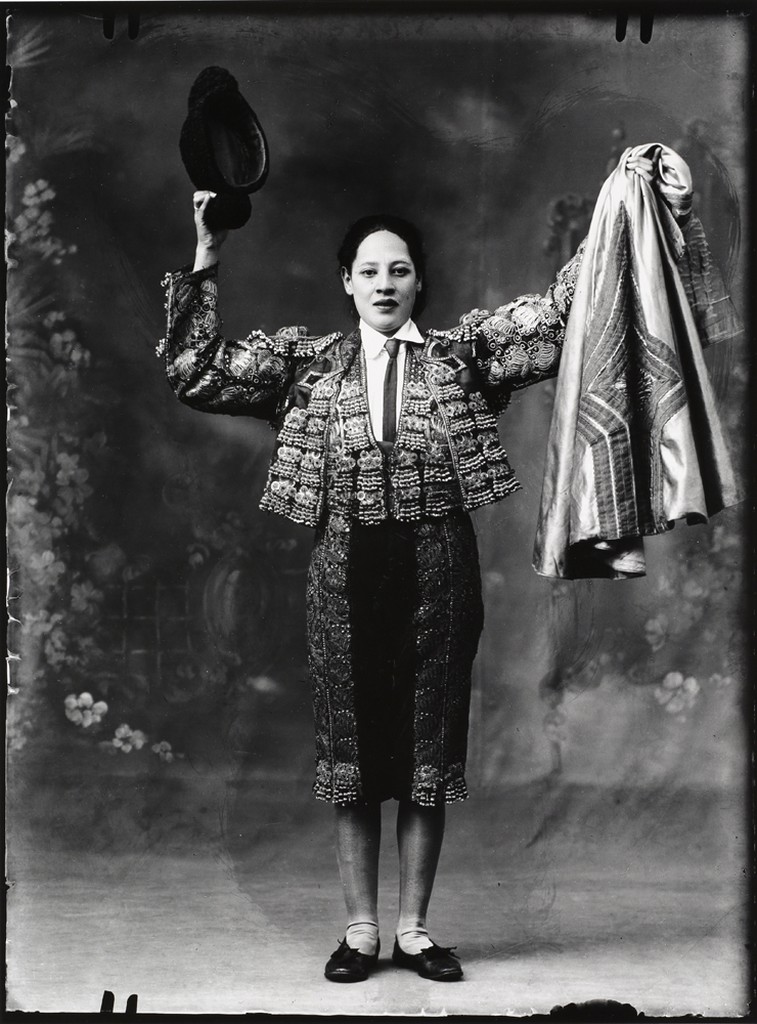

Cataloguing and celebrating the work, migration, landscapes, and customs of primarily Quechua-speaking peoples in the Peruvian Andes, where the Inca empire reigned until the late sixteenth century, Chambi’s images form a mesmerising record of the effects of social and political marginalisation; while at the same time seeming nearly to sing, in festive tribute, to such communities, his own.

“He was the first great photographer not to regard us through the eyes of the colonist”, observed Sara Facio, founder of the Museum of Latin American Photography in Argentina (Hopkinson, 2). “I am representative of my race”, he said himself: “my people speak [through]my photographies.”

I’ve never practiced or studied in the visual arts, and so my response to photographs tends to be intuitive and instantaneous, rather than analytical and honed. In so far as I’m able to classify my preferences, I seem to share François Truffaut’s belief, “that a successful film”, for example, has “simultaneously to express an idea of the world and an idea of cinema,” and moreover to sympathise with his demand “that a film express either the joy of making cinema or the agony of making cinema.” I expect the same from photography.

I’m most attracted to those artists who deploy their techniques and draw on their chosen traditions skillfully, of course, but also with a view to making a statement on reality. And by reality, I mean any space of experience and interaction in which other people – their rhythms, labours, presence, and visual attention – are implied or acknowledged.

Also with Truffaut, I like to glimpse, if I can, something of the artist’s own peculiar passion from the work they’ve produced: to trace beneath the surface of a photograph, or indeed a poem, some shadow of that human fixation, that otherwise private and unresolvable neediness and knottiness, which partly impelled its making. In other words, I go back to images and artworks that seem, however delicately, to dramatise a tension I also feel in my own life, between outwardness (love of the world) and introspection (the ability to self-examine). These, broadly, give some indication of the shaping concerns, and no doubt also the limitations, of my appreciation for photography: what I look for, and why.

Such reflections also drive to the heart of what I found, and what I value so much, in Martín Chambi’s work specifically. By approaching his “people” in a spirit of creative sympathy and affection, camera in tow, he was also, I believe, asserting and defining his own life in the world: taking a side, but in a way that affirmed his deepest needs and sense of belonging; the instincts of his evolving self, as an inheritor of Amerindian culture in a rapidly, often violently modernising era. All of this, moreover, shines, easily and entrancingly, in the images he left behind.

Importantly, to the extent that he was photographing indigenous, peasant, and labouring people as people, with the warmth of recognition and respect, Chambí was not only offering a series of social documents on his time, but elaborating a visual rebuke to those discourses and forces (of metropolitan disdain, colonial hegemony, economic plunder) that thrive on the invisibilisation of some classes and communities, and the elevation and sanctification of others. His photographs are a defiant counter-narrative to the schematism, relentlessness, and embedded calculation of such world-histories.

Within (or alongside) this quality, however, is another. In fact, there’s a baseline atmosphere in Chambi’s work, difficult to describe, but which I find totally captivating. Its main element, I think, is intimacy: an intimacy, reached for and reciprocated, with his subjects. In real terms, after all, almost anyone can point a camera in a given direction, and click: anyone can take a photograph. But it’s surely a rare observer who can sight and salute, in every other portrait, the exact individual and their humanity. Trawling his work today, it’s as if Chambi has seen some inner light in each person, each scene, a light that even they had only been foggily aware of before, and handed it back to them, in praise and thanks – for it was theirs to give, theirs to keep.

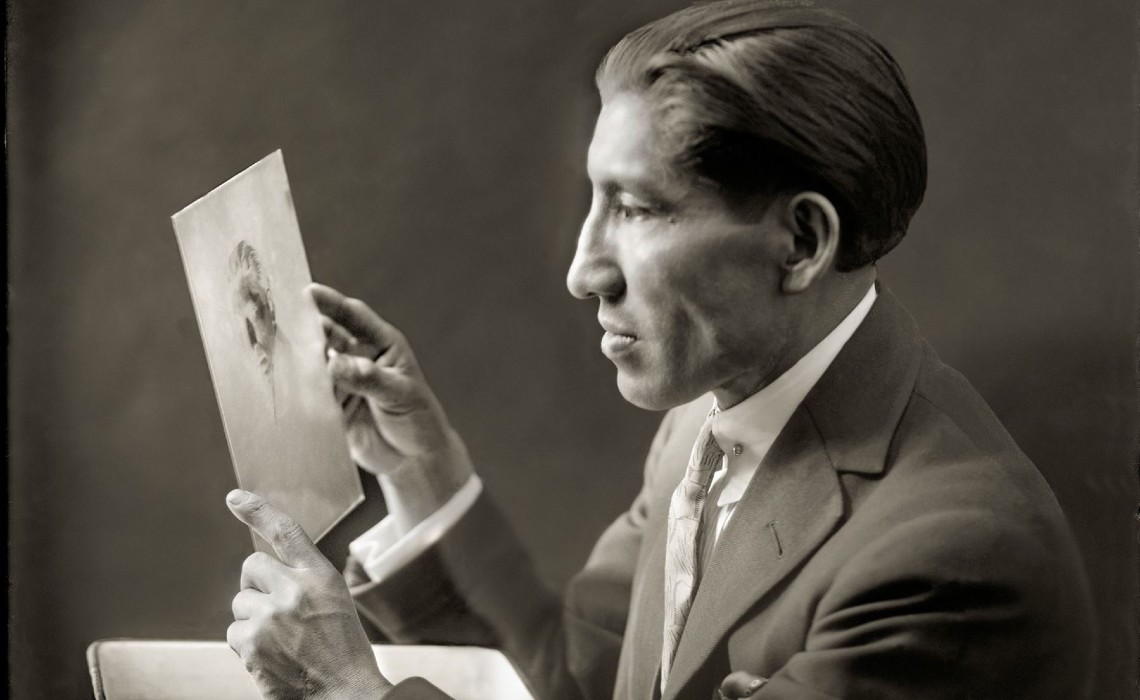

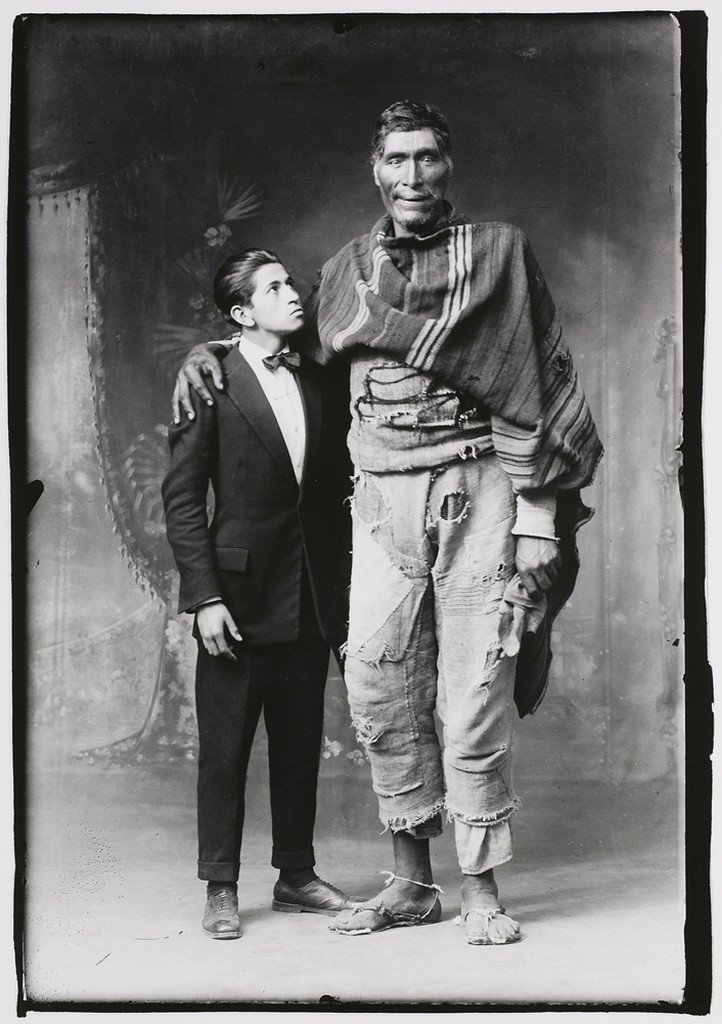

I’m thinking of the so-called “Giant of Paruro” (7 ft tall), pictured by Chambi in 1925: the gentleness in his face and hands, the intense, unobtrusive quiet of his stance, raggedly clad and yet majestic. Or a year later, the portrait of Miguel Quiespe, known as ‘El Inca’ after tramping barefoot across the mountainous region of his native Paucartambo, organizing for the cause of land rights and reform; later (I learn) he was found dead in Lima, assassinated. He sits before the camera, both statuesque and bristling, in native garb, seemingly immersed in thought, as he raises a (criminalised) coca leaf in one hand, his eyes turned downwards, hidden in shadow and light. Then, one of my favourites, a photograph in which Chambi himself appears, pacing a hand-woven, local rope bridge in Cuzco, 1929, a trail of bent-backed, quick-stepping pedlars passing on either side of him, as they haul their loads against a backdrop of wide, sun-white sky.

And there are many more: carefully glanced and emotionally laden images of life and the living, in the far reaches of an epoch hostile to both, promising only poverty and physical erasure. In Chambi’s work, by contrast, every presumed margin seems to gleam, a vital centre and a known locale, human to the root. Linger long or attentively enough over these pictures, and you might just hear their chatter and talk, the lithe exchange of their moment, break out – photographer and friends, laughing shyly with one another.

Speaking for myself, I look at these social portraits with a sensation that blends vivid familiarity and strangeness, awake to the dauntingly vast distances (of time, place, circumstance and experience) over which my nevertheless visceral certainty of identification must travel. Perhaps this is an effect of the artist’s own kinship: the impression, always, that the particular gaze – directed as it may be, curated as its chosen vistas undoubtedly are – is not so much motivated by acquisition and judgement, fixing people in their places, as filled by what is surely a kind of joy, the capacity for human affinity and recognition.

As our twenty-first-century pandemic rages on, as vaccines are tested, staggered, and accumulated unevenly across the globe, I realise that we live in an era, as Eduardo Galeano once said, “of powerful centres and subjugated outposts”, ruled by regimes of in-/visibility and engineered inequality – whose dominance is never total (267). I believe that’s why these photographs speak so eloquently: with their art, vision, feeling, and friendship. We still live in Chambi’s world.

References

Eduardo Galeano, The Open Veins of Latin America (NYU Press; New York, 1973/1997).

Amanda Hopkinson, Martín Chambi (Phaidon; London, 2001).

François Truffaut, The Films in My Life (Da Capo Press; Boston, 1994)