The palpable relief being felt by many over the accelerating approvals of apparently safe and efficient Covid-19 vaccines is hardly surprising. But away from triumphalist headlines, partially satiric messages have circulated widely on social media essentially stating: “I can’t wait for a new vaccine to come out so I can refuse it.”

These are easy to dismiss as frivolous, or the ravings of an unhinged libertarian fringe, but such statements also evoke a frequent paradox in Western societies; namely calls for scientific breakthroughs to benefit the health of all, while maintaining a scepticism about public health measures enacted by governments and reliant on a mercantilist pharmaceutical industry. And more ominously, concerns over anti-vaccination lobbying distract from life and death issues surrounding equitable vaccine access for a large portion of humanity.

Edward Jenner 1749-1823.

Pitfalls of the Public Good

Heralded as a milestone among Enlightenment advances, Edward Jenner’s late 18th century inoculation of his gardener’s son with cowpox is a path well-trodden by medical historians. In attempting to provoke an immune reaction to the far more dangerous smallpox virus, this precursor to modern vaccination built on centuries of traditional practices, notably in Africa, the Middle East and East Asia.

By subsequently infecting his test subject with live variolous matter to prove his point, Jenner likewise carried on a long tradition of dubious experimentation. Despite minimal understanding of disease transmission – let along virology – vaccine development has consistently provoked opposition, whether political, philosophical, spiritual, or from scientists themselves.

A significant factor in the dramatic European demographic expansion over the course of the 19th century was the spread of smallpox vaccination. There is a reasonable corollary between the broadening of States’ responsibilities over health matters and the emergence of openly anti-vaccine movements. Both processes accelerated during the Pasteur-Koch era even as the array of infectious diseases that were understood and potentially preventable expanded.

Uncertainty and disbelief shifted to the questioning of the basic premise of vaccination, manufacturing conditions, and even the means of prescription to a population. More familiar incarnations include arguments over the presence of aluminium adjuvants; discredited studies pointing to the occurrence of autistic disorders; the possible corruption of decision-makers for the benefit of laboratories; or a broader discordance between the interests of the pharmaceutical industry and those of public health.

A succession of scandals led Ben Goldacre in Bad Pharma: How drug companies mislead doctors and harm patients (Fourth Estate, London, 2012) to write: “I think it’s fair to say that anti-vaccine conspiracy theories are a kind of poetic response to the obvious regulatory failure in medicine and in the pharmaceutical industry. People know that there is something a little bit wrong here.”

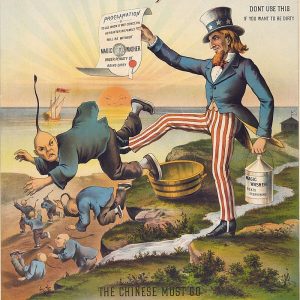

Far from being solely a European issue, health coercion, including the authoritarian imposition of mass vaccination, has unsurprisingly manifested itself in colonial history. A highly toxic plague vaccine developed in India was tested on prisoners (along with the microbiologist responsible for its discovery), before being made obligatory for Chinese residents of San Francisco during an outbreak of Bubonic plague in turn-of-the-century San Francisco.

An 1886 advertisement for ‘Magic Washer’ detergent: ‘The Chinese Must Go’.

Attempts to tackle African sleeping sickness are similarly striking. The example of pentamidine in the 1940s, an antibiotic which was believed to treat sleeping sickness (ten million preventive injections would prove as useless as they were dangerous), highlighted not only the irrationality of colonial policies in place at the time, but also a blind faith in scientific progress. Public health policies could indeed seem far removed from what was being referred to as the common good.

Past failings and Understandable Reservations

Vaccines have since become a highly symbolic element of the State’s power over the human body, with objections today frequently based on claims of infringement on individual liberties. But while the dismissal of scientific evidence is disturbing in and of itself a far more sinister side exists, the assassination of health workers administering polio vaccines in Pakistan being an obvious example.

As opposed to a demonstration in national power it is rather a question of a State failing in its responsibilities, be it through limited health infrastructure or outright negligence. And the CIA’s fake Hepatitis B vaccination campaign used to determine the whereabouts of Osama bin Laden in 2011 has hardly reassured those living in areas beyond the government’s remit. Rather, long-standing doubts about the motives behind mass vaccinations have been reinforced.

Delta Force GIs disguised as Afghan civilians, while they searched for bin Laden in November 2001

A comparable incredulity can be observed at present in Europe, where compliance with health measures taken by various States to fight the Covid-19 pandemic remains closely linked to the trust of populations in their respective governments – a trust that has unfortunately long since been waning in many societies. Hopes in scientific research for the health of the greatest number of people is confronted with the reality of a mercantilist pharmaceutical industry, or even the possible instrumentalization of public health by certain opportunistic governments to suppress pre-existing social discontent. All amidst a backdrop of wider deteriorating democratic norms and respect for basic human rights.

Debate, or Lack Thereof

While it is undeniable that an army of researchers was required to secure a Covid-19 vaccine, a cynic would question the speed with which pharmaceutical companies have developed a serum for a large and clearly solvent market, while many diseases remain outside the agendas of these laboratories. The legitimacy of a vaccine passport can also be challenged, not only because its medical effectiveness is still questioned by many, but also because it could prove a powerful deterrent to migratory phenomena and the right to asylum. The well-intentioned rush to digital health could unfortunately prove to be an additional obstacle for many countries for which access to Covid-19 vaccination may be late or even logistically impossible in view of refrigeration requirements.

If there is one matter on which there should be a consensus among populations, it is that of equitable access to these new therapies, especially given the infusion of public funds to finance the research. In particular, the terms of agreements between laboratories on the operation and licensing of Covid-19 vaccines should be made public and openly debated.

Whether or not one is convinced of the merits of vaccinating at this time against this particular virus; whether or not one questions the way this pandemic has been managed by our respective governments; and whether or not one criticises the manufacturing conditions of the serums, it would seem deeply naive to leave in the hands of competing economic powers one of the essential pillars of any society: the possibility of preserving the health of the greatest number of people. The history of vaccination, despite all the missteps and at times understandable reservations, provides an apt demonstration of this goal.

Featured Image:

The authors are researchers with the Research Unit on Humanitarian Stakes and Practices, Médecins Sans Frontières – Switzerland. The views expressed in this article are theirs and in no way represent the organization to which they belong.