The bomb might be dropped any time soon now, apparently.

The end of all ends, a nuclear war, looms among the narratives of where Ukraine and Russia’s war might end. Timothy Snyder warns in this regard that a nuclear bomb ‘would make no decisive military difference’; adding that looking at ‘the mushroom cloud for narrative closure, though, generates anxiety and hinders clear thinking. Focusing on that scenario rather than on the more probable ones prevents us from seeing what is actually happening, and from preparing for the more likely possible futures.’

As much as we can agree with this statement, and as much as it is nothing but a prediction for one of the possible futures, other geopolitical analysts such as the Italian Lucio Caracciolo warn of the ease with which the nuclear option has entered public discourse, the talk shows and political debate.

What now seems evident after Ukraine’s successful counter offensive in the north, and the ongoing systematic bombardments on its energy infrastructure, is that hostilities are continously escalating and we should prepare for a new phase in this war. If the unspeakable does happen, it will coincide with a new era of warfare. Maybe the last.

How we develop historical awareness, and a particular narrative, depends more and more on which side of the Iron Curtain 2.0 we fall. For all our apparent enlightenment, time and again, we show ourselves incapable of building diplomatic bridges without brandishing the Sword of Damocles.

The Bomb might be dropped anytime now. But a cultural bomb, the normalization of the possibility of nuclear war, has already dropped from the virtual skies that we carry in our pockets; conveying an endless stream of images, produced by and for everyone, but curated and filtered by a few.

No one can say when it started dropping. Maybe with the invasion of February 24, or maybe 2014. Some say even 2001. Regardless of the date, we join other generations of humans that must now worry about the existence of nuclear weapons; of the apocalypse.

The first shockwave comes in the form of war’s inevitability as soon as Russia’s tanks began rolling down towards Kiev; until the last moment many, including me, were unconvinced the troops amassed at the border would ever march. The taboo of a land war directly involving nuclear superpowers was still intact.

We are generally shielded, or not even exposed, to pictures revealing the true horror of warfare. For the most part, what is put in front of us depends on the political agenda of warring superpowers or various forms of commodification of suffering. One wonders whether we are now even capable of autonomously creating our own memories; or freely perceiving the present and past, never mind the future under such conditions of conditioning.

The effect of an endless flow of images, tailored and auto-curated to arouse emotions – residing alongside our most intimate obsessions – requires acknowledgement. Their capacity to induce fear and trigger desire are the preferred tools of contemporary propaganda and such tools are used by both side of the Iron Curtain 2.0.

Even the posture he had to adopt to do so was symbolic. He had to bend down, to lower himself, in order to commit the ignominy of his seeing his own face … the creator of the mirror poisoned the human race."https://t.co/gtJMu7XUA3

— Frank Armstrong (@frankarmstrong2) September 7, 2022

Global Civil War

The political consequences of a lack of cognitive freedom in response to weaponized imagery and information are not new in history but, as with every historical constant, is a question that ought to be explored.

The times we live through are what the philosopher Franco ‘Bifo’ Berardi calls the Global Civil War, where:

‘[…] relations among individuals are wired and subjected to automatic connections: political power, therefore, is replaced by a system of techno-linguistic automatisms inclined towards the automation of every space of life, cognition and production.’

For example, how we react to the pictures of Nord Stream II’s bubbles or the Crimea Bridge strike, depend mostly on which conveyer belt of opinions and positions (“the techno-linguistic automatisms”) we find ourselves exposed to.

The same goes for how we perceive the veracity of the images of the massacre of Bucha, as well as Russia’s depiction of neo-Nazism in the Ukrainian armed forces, which was previously extensively covered in our media as well.

Voraciously consuming images of war – of a particular war – I often consider the extent to which images are being used to perpetuate suffering rather than end it.

Just like in the times of COVID-19 – if your memory stretches back that far – it now takes a great deal of discipline to regulate the right dose of news consumption, as the induced anxiety can be overwhelming. Never mind the moderation necessary to digest and discuss it; or put ourselves in another’s shoes.

With a diabolical enemy in our sights, such as our culture demands, as well as a defined timeline of events, wherein we struggle to look past February 24, 2022, we weary of discussing strategic failures – reckless dependence on Russian gas – and broken promises – NATO’s expansion eastwards despite undertakings – over the last two decades by Western governments.

Are we capable of comprehending and reconciling Russia’s (not just Putin’s) very real phobia around encirclement – something that history teaches us is hundreds of years in the making – alongside Ukraine’s legitimate path to independence, which also goes back centuries? Is there now scope for rational dialogue?

Frank Armstrong recalls his travels through Ukraine in 2015 with words and images, at a time when the drumbeat of war was already evident.https://t.co/gky3z3ajZN@broadsheet_ie @BowesChay @MattChristmas @WhistleIRL @danieleidiniph1 @j_reilly33 @danwadewriter @KevinHIpoet1967

— CassandraVoices (@VoicesCassandra) March 5, 2022

Filo-Putinisti

Recently, one of Italy’s most prominent newspaper, Il Corriere Della Sera, published the names and pictures of ‘influencers’ who, allegedly, the Kremlin benefit from. Labelled ‘filo-Putinisti’, among these are independent journalists, academics and politicians, treated as ‘enemies of the people’.

It is not very different to how Clare Daly and Mick Wallace have been treated by the Irish Times.

To call for a strategy that would include negotiation with Putin’s regime would be to go against what Italian journalist Nico Piro calls the ‘Pensiero Unico Bellicista’ (Unique Bellicose thought current). Unequivocaly taking NATO’s side is what counts. Whoever doubts the legitimacy or even the sanity of ‘interventionism’, even in the closet, is accused of aiding and abetting the enemy.

How is it that we have been shielded from what has been happening in the Donbass since 2014? Fourteen thousand died in brutal trench war raging at the edge of Europe. Now, suddenly, we feel the heat of the battle across Europe, and simultaneously wonder whether we will have sufficient energy to heat our homes.

Let’s keep pretending Putin’s invasion came as a surprise. Countries don’t invade each other anymore. Nuclear superpowers don’t engage in land wars anymore. Right?

The mnemonic silence over the war in Donbass, has morphed into a cacophony of coverage in the wake of a fully fledge invasion, filling, for months, the void left behind by the receding pandemic, as ominously Europe faithfully follows the dictates of a declining US Empire.

Actually, it seems that as much as rest of the world is preoccupied and even annoyed with Putin’s invasion, it is now giving the finger to the West, after centuries of exploitation.

It seems incredible how the US, apparently so tired of being an Empire, and on the retreat elsewhere, is still willing to unleash the most pervasive and subtle of propaganda campaigns, suppressing dissenting opinions in countries it sees as vassals, perhaps in order to preserve itself, or what is left of its power.

This is no time for negotiation is the message, or better still, there was never time for any. Negotiation cannot occur with a genocidal dictator, or can they?

The propaganda operates not just to change the narrative of the past; it makes one forget that there was a past; or that the past is always brought to us through competing narratives on the battlefield of time and discourse.

Now, with our sense of time destroyed, and with that an opportunity to discuss, and possibly negotiate, we become more and more ready, and even eager, to kill one other. This is the paradox of a time we had dared to call the “End of History”.

The Dust

To remember is, more and more, not to recall a story but to be able to call up a picture.

Susand Sontag, Regarding the Pain of Others (2003)

As Susan Sontag remind us, representations of war and suffering have a long history and contain codes of production and consumption: From Goya’s print series The Disasters of War; to Fenton’s Crimean war pictures; Picasso’s Guernica; and pictures of the 9/11 terrorist attack exhibited in the exhibition ‘Here is New York’.

Francisco Goya Disasters of War – Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen

Nonetheless, exposure, or really, the immersion in the infosphere, where the weaponization of images and messages is unprecedented, cannot be compared to any of the previous decades of warfare.

There is now an overwhelming revival of violence in this all-pervasive info-sphere. The message of its inevitability seems a deliberate imposition to distract us from those past and present voices with a lot more to say than a fleeting frame destined to be rapidly replaced in our compulsive doom-scrolling.

At the same time, it devalues those frames, often taken by the rare photojournalists who are able to go where it really matters – at great risk to their lives – and actually convey what their subjects are unable to. Often because they are dead.

The curated, over-mediatic exposure of one tragedy instead of another is not really a novelty in the way we use and experience imagery of a current context of interest, but, as well explored in a recent podcast by the Economist, we live in a radically more transparent battlefield.

The abundance of what is called Open Source Intelligence data, of which photography is a key component – its democratization as with the latest Iranian protests – is to be welcomed, even if it is a double-edged sword.

On the one hand, we can say that we have never had as many tools available to us in the search for truth. On the other, the concept of truth, or what is truthful, has never eluded us to such an extent as in recent times.

In an attempt to clear the view amidst the Fog of War, we create individual, atomized fog, which follows us wherever we go.

Little wonder that in our so-called liberal-democratic hemisphere we have no idea how to bring democratic oversight to social media platforms; even leading some of us to cheer on the idea of Elon Musk, the richest man on earth, taking control of such a decisive device for dialogue and confrontation as Twitter.

No amount of moderation, fact-checking, algorithm-driven-filtering or surveillance, can keep pace with the endemic disinformation present in our feeds; as much as no amount of critical thinking, rational argumentation and corroboration can prevail over a propaganda machine built right inside our minds.

“We have no doubt we will prevail.” As the war in Ukraine enters a critical new phase, the country’s First Lady, Olena Zelenska, has become a key player—a frontline diplomat and the face of her nation’s emotional toll. https://t.co/DCXWYnzAsK pic.twitter.com/wcaY5IFGHf

— Vogue Magazine (@voguemagazine) July 26, 2022

In Vogue

There’s little doubt that photography carries the popular connotation of bearing truths: ‘the image doesn’t lie.’ But we don’t need not look too hard to work out how easy it is it for a photograph, and its caption, if not to lie, to deceive. If not to manipulate, then to be as alluring as a Vogue feature can be.

Annie Leibovitz’s photograph of Ukraine’s First Lady Olena Zelenska before a grounded Antonov plane and surrounded by fierce special forces is, in my modest opinion, a photographic masterpiece.

Having said that, going through Rachel Donadio’s piece, and Leibovitz other pictures I recognise how instrumental this is to the current war struggles. Via the gloss of what many desire – to be a celebrity or to become a hero – the image of a presidential couple of a devasted country becomes something we aspire to.

With each blast we feel more and more impotent at creating the conditions for dialogue to occur. Is it possible that neither Putin’s Russia and his allies, nor the West, composed of thirty NATO members supporting Ukraine is willing to take a step back from the brink?

How are we to create the conditions, if the dominant message is one founded on our utter impotence, because it’s always the other sides fault?

Hannah Arendt remind us in her essay “On Violence” that

It is often been said that impotence breeds violence, and psychologically this is quite true, at least of persons possessing natural strength, moral or physical. Politically speaking, the point is that loss of power becomes a temptation to substitute violence for power […] and that violence itself results in impotence.

If we are actually talking about the possible, and rational, use of the most powerful weapon available it is exactly because power is slipping away from the Western alliance, as much as from Putin’s regime.

Nothing new in that as the re-allocation of power is one of the preoccupations of history itself, seldom unaccompanied by violence. But what does it mean when the existence of nuclear arsenals capable of causing our premature extinction are carelessly normalized as facts of life? Like any other storm. Like any other crisis. Like something we’ll remember. You see the path? And where it leads?

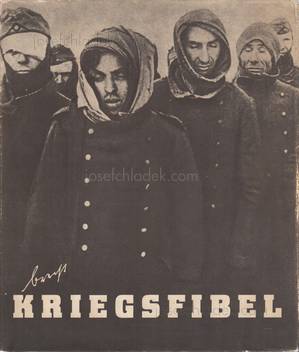

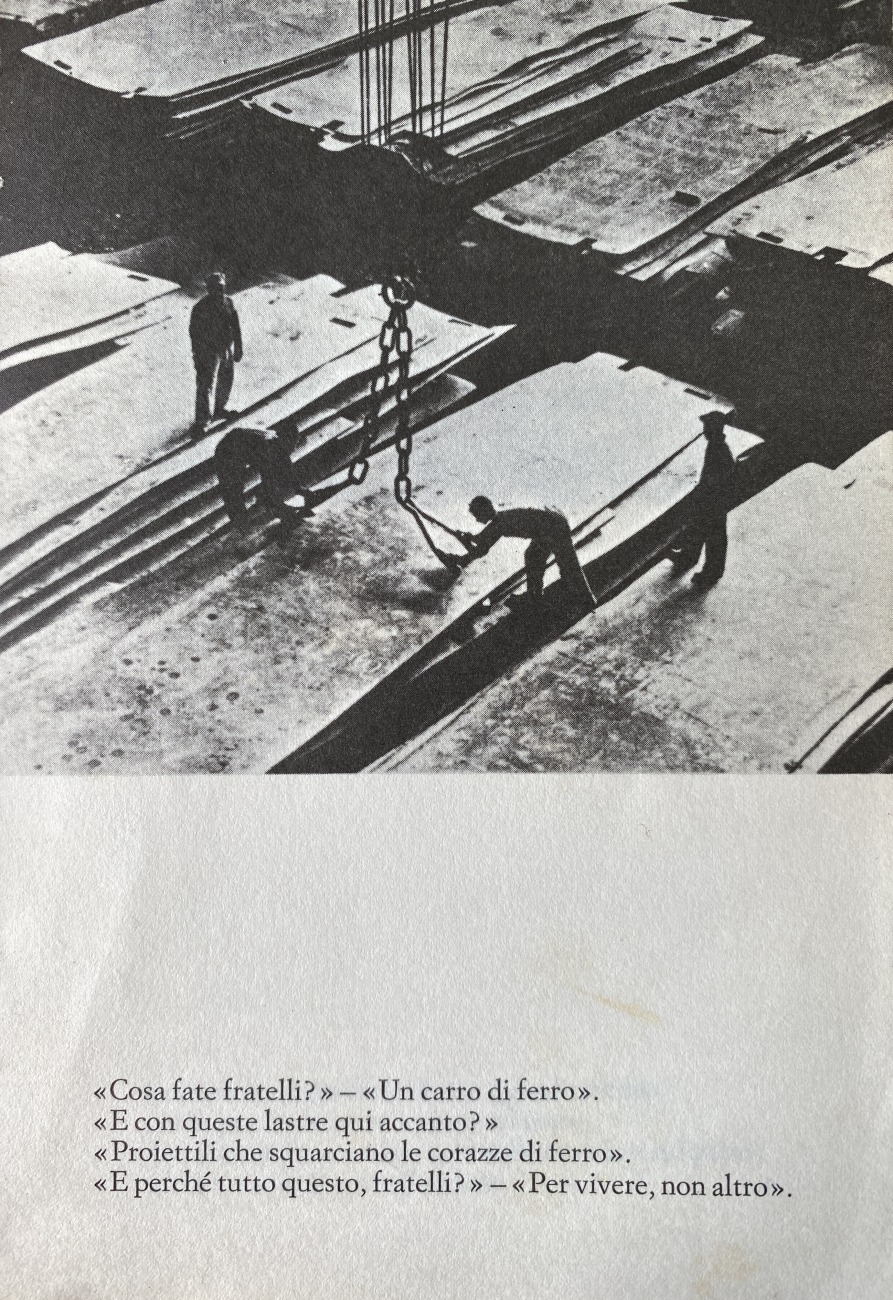

In 1955, Bertolt Brecht published a book called Kriegsfibel or War Primer. It was a collection of photographs, cut out of newspaper and magazines, which he re-captioned with his own verses.

Such a document now exists not only thanks to Brecht’s artistic sensibility, but also because new generations survived to look at it again.

“What are you doing, brothers?”-“An iron tank”.

“And with these slabs here?”-“Bullets that will pierce those Iron armors”.

“And why all this brother?”-“To live, nothing else”. From Bertolt Brecht’s Kriegsfibel