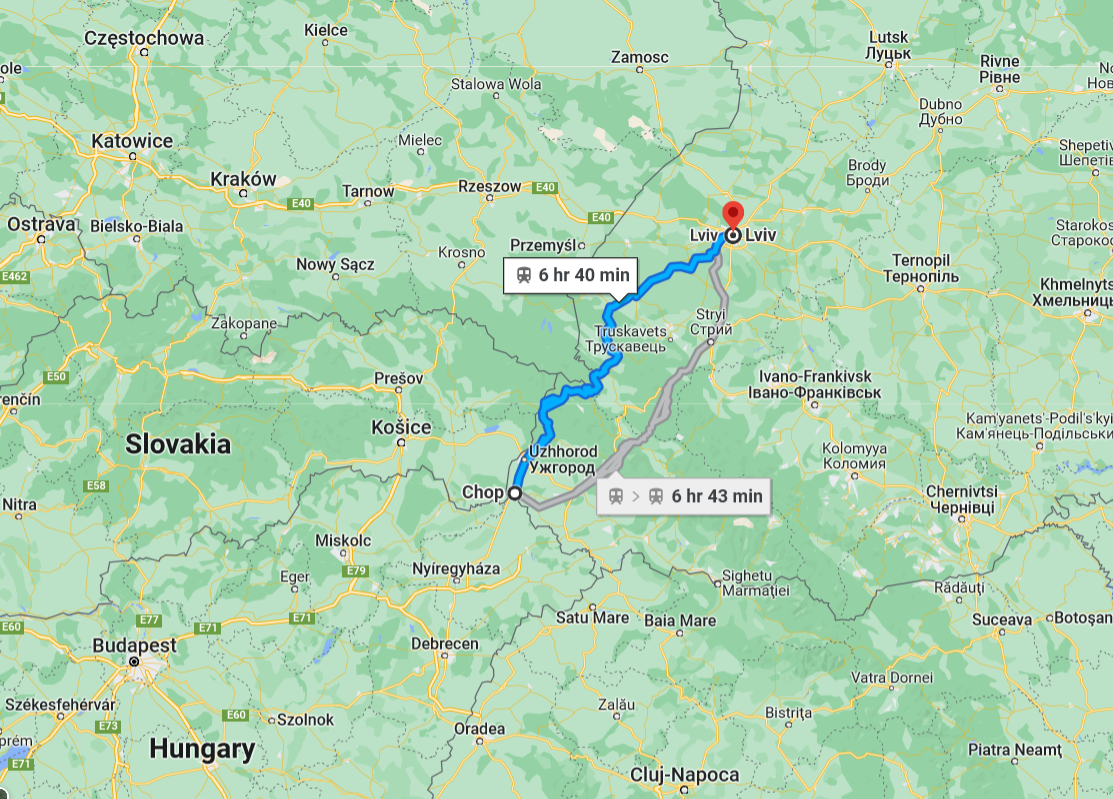

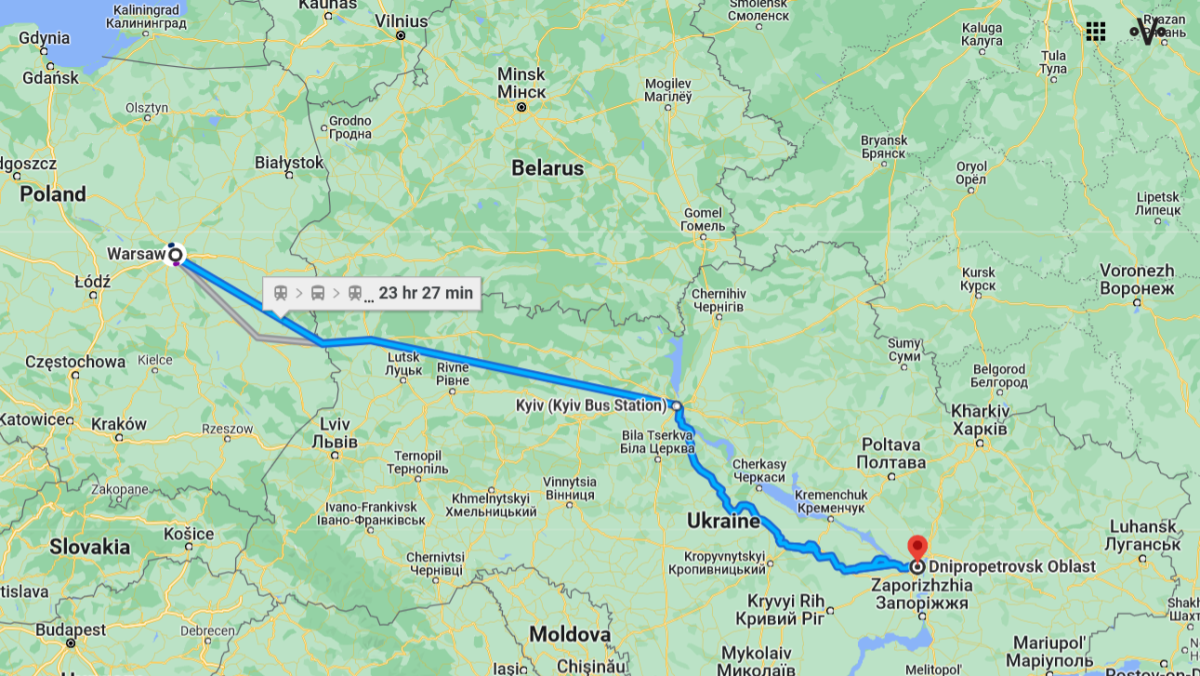

Frank Armstrong recalls two overland trips into Ukraine in 2015. The first was through the former Czechoslovak territory around Uzhhorod, as well as the former Polish city of Lviv or Lviv. Later that year he travelled by bus as far as Kiev and then east as far as Dniperpetrovsk.

Part 1 Summer, 2015

Crossing from Slovakia into Trans-Carpathian Ukraine at the Çop junction, trains from the West halt in deference to the different rail gauges used on the other side. Stalin contrived this to prevent easy entry for invading armies; or escape. Crossing the frontier into the former Soviet Union might instil a little trepidation even into a seasoned traveller.

Çop train station.

An illuminating mural in the cavernous train station depicts heroic scenes of a triumphant Socialism. Beyond at the platforms, trains retain wooden benches that recall another age. I knew I had left a rapidly converging Europe when the conductor smilingly declined payment after I presented too large a denomination.

I was among three other visitors to Ukraine arriving by train from Slovakia, although a border guard told me frequent car trips are made to avail of cheap petrol. The frustration of waiting inside a stationary carriage – akin to a panelled sardine tin – during a heatwave was offset by the friendliness of customs officials who simply checked for contraband medicines. No visa is required for EU visitors but the continued low-level warfare in the faraway east is deterring visitors despite a favourable Euro to Hryvnia exchange rate.

The River Uzh in Uhherod.

Borders are often a legacy of ancient battles or coincide with impassable mountain ranges or rivers that deterred conquest and absorption. A change in topography often gives rise to socio-economic boundaries; shifts from upland, semi-nomadic pastoralism to settled arable land bringing larger settlements: different political regimes and ethnic compositions may arise.

On the road between Uzhhorod and Lviv.

But twentieth-century Europe brought more artificial borders imposed by distant remote peace treaties or later omnipotent Superpowers, and saw the decline of multi-ethnic empires. Thus, Hungary was reduced from one part of a dual Austro-Hungarian Empire to a disgruntled rump that ruefully surveys its over two million ethnic brethren in neighbouring countries. The hated Treaty of Trianon after World War I was reflected in that country’s alignment with Nazi Germany during World War II. Revanchist Hungary remains a potential source of instability.

Traditional hay stacks between Lviv and Uzhhorod.

There is no obvious difference in terrain between Trans-Carpathian Ukraine and eastern Slovakia, and the region contains a sizeable Hungarian minority. Yet as one travels into the surrounding countryside a different agriculture becomes apparent: a shift from the ubiquitous cash crop of maize on the Slovak side to traditional hay stacks in Ukraine, seemingly gathered in traditional manner with scythe and pitch fork. Since the twentieth century, political frontiers have acted like natural boundaries accentuating patterns of development.

On the road between Uzhhorod and Lviv.

In Eastern Europe north of the Balkans, the legacy of Soviet victory in World War II remains largely intact. Apart from the relatively amicable separation of Czech Republic from Slovakia in 1993 the frontiers are unchanged. The recent land grab by Russia of Crimea and incursion of irregular troops into Donetsk may herald a more turbulent phase in European history. Borders rarely shift without an accompanying tide of blood, even more perilous in an era of mutually assured destruction.

Lviv

The most dramatic territorial legacy of World War II was Poland’s westward shift, forcibly ceding significant territory to the Soviet Union in return for large swathes of eastern Germany. Millions of Poles were removed from their ancestral homes and re-located in the west. Among the territory lost was the historic city of Lviv (Lvov to Poles) to Ukraine.

Prior to World War II, it contained a population two-thirds Polish. It is now almost entirely Ukrainian although reminders of the Polish period include a statue to their national poet Adam Mickiewicz, who was actually born in Vilnius, the capital of Lithuania.

Lviv.

Lvov was annexed by the Austrian Hapsburg Empire (and re-named Lemberg) in 1772, in the first Partition of Poland, becoming capital of Galicia which was the poorest province of the Empire. But this period left a remarkable architectural legacy that prompted UNESCO to designate the historic centre as ‘World Heritage’.

Today Lviv as it is now called is relatively prosperous, drawing a large number of tourists from neighbouring Poland. Predictably the old city is fringed by a swathe of functionalist Soviet-era apartment blocks, but it retains an abundance of old world charm and the hum of cafés that spill onto carless streets.

Lviv.

There are nonetheless signs of a country at war with stands erected by the extreme nationalist Svoboda Party supporting the war effort and offensive toilet roll featuring a picture of Vladimir Putin available in souvenir shops. I spoke to one women of student age who railed against a terrorist, separatist threat to the integrity of the state. She could have been mistaken for someone referring to the existential threat posed by ‘enemies of the people’ in Soviet times. The uncompromising language of extremism is unmistakable.

Lviv.

The demise of the archaic, multinational Hapsburg Empire after World War I might be seen as the death knell for so-called Mitteleuropa. Most successor states that emerged in the Versailles settlement were inspired by a nationalist vision promoting a singular cultural identity, and hostile to diversity within the confines of the state. In contrast during the imperial era cities at least were a mosaic of religious and linguistic groups.

Market stall, Lviv.

The population of ethnically variegated Mitteleuropa was particularly unsuited to the identification of a nation with a single state that reached a violent apotheosis with the Nazi ideology of the master race.

Lviv.

Transnational Jewry were the most obvious victims, but anti-Semitism was not limited to the Nazis, continuing into the Cold War-era: as late as the 1960s thousands of Jews fled Poland in the wake of a number of purges.

Jews had flocked to Poland in great numbers at the end of the Middle Ages due to the tolerance shown there compared with in the rest of Europe. It became known as paradisus Iudaeorum (paradise for the Jews) and contained two thirds of the continent’s Jewish population. Great centres of learning were establish in cities including Lviv, and agrarian settlements known as shtetl that contained many layers of Jewish life dotted the countryside. There Yiddish, a Germanic language written in Hebrew script, found its highest expression.

Lviv.

The writings of Joseph Roth (1894-1939) recall the extraordinary cultural diversity of the Austro-Hungarian Hapsburg Empire. Born a Jew in the city of Brody near Lviv in the province of Galicia, The Radetzky March is a paean to the fallibility of that Empire; his journalistic account of Eastern European Jews, The Wandering Jews, remains a valuable insight into the remarkable diversity of the Jewish populace.

Roth despised the numerous frontiers erected in his lifetime, that impeded his passage and that of many others throughout Europe. He wrote

a human life nowadays hangs from a passport as it once used to hang by the fabled thread. The scissors once wielded by the Fates have come into the possession of consulates, embassies and plain clothes men.

The possession of a particular passport at that time was indeed a matter of life or death.

A melancholic alcoholic, Roth committed suicide in Paris in 1939 just before the Europe he knew was consumed by the fires of hatred.

The Versailles settlement also created what now seems the curious state of Czechoslovakia, stretching almost a thousand miles from east to west, as a homeland for Czechs, Slovaks and Ukrainians (or Rusyns as they were then known), but also containing large and disgruntled German and Hungarian minorities.

In the aftermath of the Munich Agreement of 1938 which dismembered that country, the far eastern province of Ruthenia containing most of that Ukrainian population was annexed by Hungary, but was transferred to Ukraine itself after the arrival of the Red Army in 1945.

The First Czechoslovak Republic was a microcosm of the Hapsburg Empire with republican institutions. Although clearly dominated by its Czech constituent, many of its first leaders such as Thomas Masaryk were socially progressive, and eschewed narrow-minded nationalism.

It is perhaps Europe’s tragedy that his vision of a multi-ethnic democratic state did not endure.

The Europe of Joseph Roth and Thomas Masarky was torn asunder by the twin hydras of Nazism and Stalinism. Ironically one of the groups that suffered most was the German populations who were forced out of their ancestral lands across Eastern Europe, many thousands perishing in the process.

Europe is the poorer for the homogeneity of many states.

Perhaps the arrival of the idea of a political and cultural Europe might generate a more accommodating reaction to minorities, but unfortunately attitudes in Ukraine suggest the idea of Europe itself can be exclusionary, as if humans feel the need to find an oppositional Other.

Lviv.

This exclusionary idea of Europe is not limited to Ukraine as vociferous Hungary and several nearby states also identify enemies within. The Romany people remain a pitiable underclass in most places they live.

Latterly migrants fleeing political turmoil in the Middle East have been greeted by barbed wire fences on the Hungarian border.

We have yet to reach an epoch when cultural diversity is seen as a boon. It would be tragic if the political idea of a Europe, a response to the conflagrations of the early twentieth century could become the case of further conflict.

Part II, Autumn, 2015

Ukrainians like to say they live in the largest fully European country. That scale is enhanced by a transport infrastructure relying on unwieldy, Soviet-era rail and roads that are mostly potholed outside of a few stretches of motorway, as I discovered to my discomfort on a recent trip into eastern Ukraine. Moreover, with average salaries less than €200 per month travel is a rare luxury for most in this profoundly unequal society. In a country of great diversity and relative youth, national identity is fragile.

Kyiv.

The depredations of the Soviet era when Ukraine was theoretically an autonomous republic but really an integral part of a vast imperium are apparent in the unforgiving architecture of its cities. In the outskirts of Kiev, as elsewhere, tower blocks loom at heights unknown in Western Europe, and inside the capital concrete monoliths sully the splendour of a pre-Revolutionary heritage that includes the UNESCO medieval site of Santa Sophia Cathedral.

Kyiv.

The deadening weight of the Communist aesthetic recalls the advice of Marxist theorist George Lukács:

What is crucial is that reality as it seems to be should be thought of as something man cannot change and its unchangeability should have the force of a moral imperative.

In the long shadow of imposing structures and heroic monuments people would accept the inevitability of the triumph of Communism. Alas, since independence in 1991 the trend has been to replace this with the brash sheen of American capitalism, an implicit genuflection to the Cold War victor and its consumerism.

Kyiv.

Obviously architecture was the least of the excesses of Communism in Ukraine. That mantle is reserved for their great famine known as Holodomor when Stalin’s policy of de-kulakization (1929-1932) killed something between two and seven million Ukrainians and annihilated the social fabric of village life: either you took a job in a collective or went to a city elsewhere in the Soviet Union.

Kyiv.

Simultaneously, entire nations, including the Tartars who once occupied Crimea, were forcibly relocated to different parts of the empire. This destruction was compounded by the German invasion in World War II, although Ukrainians had an ambivalent, and in some cases collaborative, relationship with the Nazis during over two years of occupation.

Kyiv.

Today in Ukraine most cities in the south and east are Russian-speaking. Parentage is often, unsurprisingly, mixed: a group of young professionals I met in the city of Dniperpetrovsk revealed ancestry Ukrainian, Russian and even Tartar. All spoke Russian as their first language but considered themselves Ukrainian. Even religion, historically, did not separate Ukrainians from Russians as both followed the Greek Orthodox rite. It evoked the question: what does it mean to be Ukrainian beyond living within the borders of that state?

Kyiv

A civic nationalism divorced from the kind of destructive ethnic identification that bedevilled the break-up of Yugoslavia would minimise lethal divides. But the current taste for symbols of Ukrainian identity, such as the surge in popularity for traditional dress, suggests this is not on the agenda. Pride in cultural inheritance can easily be skewed towards atavistic violence.

Kyiv.

I discovered an increasing despondency among my new-found friends at the capacity of Ukraine’s politicians to bring meaningful improvement to the country. Each revolution, including the latest Euromaidan against the staggering corruption of former President Victor Yanukovych has brought disappointment. The oligarchs remain dominant, led from the front by billionaire President Petro Poroshenko, the richest man in the country.

According to a recent report from the Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group a desultory one in five cases against high-ranking officials ends with conviction and imprisonment.

River Dniper, Dniperpetrovsk.

The aspirations of the young and dynamic quivering at the possibility of joining the European mainstream remain frustrated. Inevitably in some quarters there is nostalgia for a more authoritarian era proximately represented by Vladimir Putin’s Russia. According to my friends in Dniperpetrovsk the divisions in Ukraine are often generational.

Dniperpetrovsk.

Nearby Donetsk is still controlled by Russian-led insurgents. An unsteady ceasefire has held there since September. There have even been attempts, as in Russia, to rehabilitate Stalin. The city was previously called Stalino. Nostalgia for the Soviet Empire is being incubated.

Russian aggression feeds extreme Ukrainian nationalism. Military build-ups have pernicious effects wherever they are found. In Kiev an array of tanks is parked outside the foreign ministry and the distinctive grey camouflage of the Ukrainian army now seems a fashion accessory, most of all for supporters of the far-right Svoboda (Truth) party.

Kyiv.

An encounter I had with one character in a Kiev hostel was revealing. When I said I was Irish he proclaimed his admiration for the IRA, and was a little put out to hear that I was not a supporter of what he perceived as another underdog fighting an imperial foe. The fighters against the Russian-led rebels in Donetsk were his heroes.

Ukraine offers huge rewards for Russia. It is an agricultural powerhouse, once the bread basket of the Soviet Union, and today is the world’s fifth largest corn producer and the largest producer of sunflower oil. Further, although corruption even extends to the awarding of degrees, its educated population especially in technical disciplines are an important asset.

Kyiv.

All nations have their myths that bind disparate groups together inside one state. The complication for Ukraine is that its history is deeply entwined with that of Russia’s. Even the name ‘Rus’ originates in the medieval kingdom with its capital Kiev established by Viking colonists before it was gradually Slavicised. Ukrainian identity was forged through contact with neighbouring empires: first the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth that once stretched from the Baltic to the Black Sea, and afterwards the partitions of Poland beginning in the eighteenth century, under the Austro-Hungarian Hapsburg Empire which served as a hothouse for numerous nationalist identities, including Zionism and Nazism.

Memorial to victims of the Holocaust, Dniperpetrovsk.

As their language crystallised in a form and with a script different to that of Russian, and poets especially Taras Shevchenko illuminated a national character, nineteenth century nationalists turned to the Cossacks as a distinguishing source of identity.

Historical Museum, Dniperpetrovsk.

Translated as ‘free man’, Cossacks were bands of escaped serfs that resisted the Catholicism of their Polish landlords and established military settlements along the Dniper and elsewhere, in the late Middle Ages. Their indomitable spirit strikes a chord with modern Ukrainians and is resurrected in re-creating of their settlements in Dniperpetrovsk’s impressive historical museum. The tragedy for the Cossacks was that after throwing off the shackles of the Polish nobility they succumbed to the Russian Empire. This has an obvious contemporary resonance.

Passing through the interior, where vast fields stretch beyond the horizon, one sees the great possibilities for this country. Encountering the wide-eyed interest of people in world affairs, their knowledge generally beyond that of their Western European counterparts, fosters a visitor’s optimism; witnessing small kindnesses from those with few possessions is touching. But the current system is failing people and the longer that endures the further the already pronounced wealth inequalities will grow, and with that the entrenchment of petty tyrannies.

Russian Dolls, Kyiv.

Membership of the European Union is not a panacea for Ukraine. Ensuing emigration could lead to a crippling brain drain, and a free market could be problematic in some sectors. But equally Europe cannot allow a new Iron Curtain to develop. In the end Ukraine needs to find an accommodation with its Russian neighbour to whose fate it is bound.

Young Ukrainians need reassurance that their country can be reformed. Countering Lukács: reality as it seems to be ought to be thought of as something we can change.

Versions of these articles were originally published in Village Magazine.