SYRIZA’s rise to power in 2015 created shock waves around the world. The international Left celebrated a victory that seemed unfathomable a few years earlier. Its electoral triumph gained even more attention than it otherwise would have, because the stakes surrounding it were exceptionally high.

The Coalition of the Radical Left, as is the meaning of the acronym, was about to engage in a crucial and tough negotiation with the E.U. and particularly Germany, regarding Greece’s debt. The party had been elected after promising to take a much harder stance in these negotiations. Analysts around the world were warning that this clash could endanger the global economy.

Nine years later, this once mighty political force that scared the world’s financial establishment, now lies in ruins. Poll after poll shows its electoral support diminishing. Opinion polls consistently show it to be in third place, trailing PASOK (Panhellenic Socialist Movement) by a small but steady difference. It is now perilously close to single digits.

Furthermore, after two recent splits (not counting the one in 2015, which will be mentioned later), and the clear and present possibility of a third one looming, it appears to have fallen into complete disarray internally, as its recent, almost farcical, convention exposed. To fully understand the trajectory of its downfall, however, we need to return to the historical context that created its rise.

José Manuel Barroso and Kostas Karamanlis in Dublin in 2004.

There is [plenty of]money…

In October, 2009, Kostas Karamanlis, president of the right wing Nea Dimokratia, the ruling party at the time, called an early election, after his party lost ground in the European elections in June of that year. In his election campaign the Prime Minister, who had been ruling Greece since 2004, was very open about the necessity of taking significant austerity measures.

On the opposite side, Giorgos Papandreou, president of the centrist party PASOK, the main opposition at the time, just a month before the election, in September 2009, uttered the phrase that was going to become emblematic in the years that followed: ‘There is [plenty of]money…’

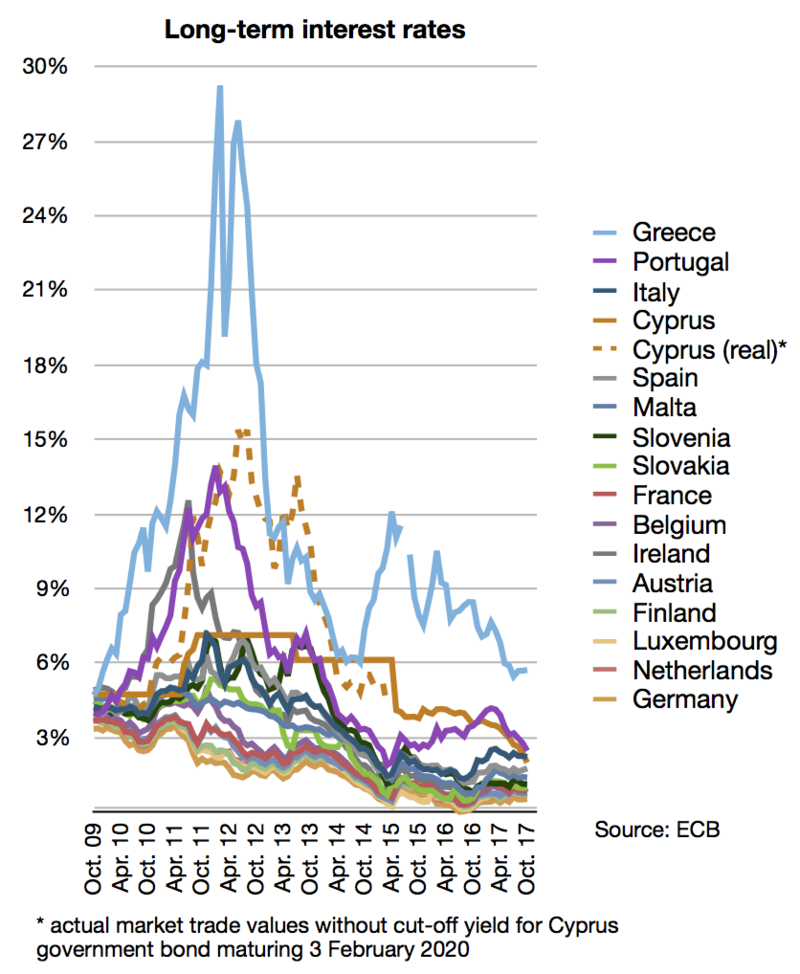

Naturally, PASOK won in a landslide, taking 44% of the vote, while Nea Dimokratia subsided to a mere 33.5%. It is important to note that SYRIZA was the last party to enter the parliament in this election with only 4.6% of the vote. Soon after his emphatic victory, however, Giorgos Papandreou had to face the grim reality of Greece’s problematic economy within the context of an unraveling global crisis, its perpetually rising debt, as well as a rising deficit, and probably worst of all, the cold determination of key players in the EU to make an example of Greece, as a means of enforcing hard line fiscal discipline across the Union.

On April 23, 2010, a mere few months after taking office, the PM made an historic announcement, from the picturesque island of Kastelorizo, at the far end of Greece.

In it, he explained that the real volume of the deficit of 2009 had just been exposed. The previous numbers had been cooked up it was revealed, which led to the coining of the expression ‘Greek statistics.’ He continued to say that his government inherited ‘a ship that is ready to sink’ and that Greece was unable to borrow money from the markets on viable terms.

Hence, he had to ask for the activation of a support mechanism from the EU, which was the colonial-style loan agreement that became known as the Memorandum. What followed was an almost decade long period of havoc, that saw Greek living standards plummet, the welfare state dismantled, and a great number of strategic national assets being sold off.

The worst shock for the citizens of Greece was in the beginning, which gave rise to massive popular protest movements, fierce clashes between demonstrators and police and a broadly acquired culture of disdain towards the political establishment. In this turbulent political climate, where governments formed and dissolved repeatedly, the two traditional big parties kept losing ground and PASOK in particular, saw its electoral base being gradually dissolved. SYRIZA, led by the young and charismatic Alexis Tsipras started gaining momentum.

Alexis Tsipras in 2008.

Leftwards

The disillusioned and desperate voters of PASOK were increasingly turning to the Left, where an up-and-coming new leader was promising another way out of the crisis, with better terms and more dignity. In the elections of May 2012, Nea Dimokratia won a Pyrrhic victory with a meager 18.8% of the vote. SYRIZA breached the traditional two-party system by coming in a close second on 16.8%, and PASOK dropped into third place with 13.2%. This was also the first time the unashamedly Nazi Golden Dawn party entered the parliament with 7%.

These results didn’t allow for the formation of a government, so a second election was swiftly called. In June 2012, Nea Dimokratia won the election again, this time with 29.6% of the vote. SYRIZA came a close second again with 26.9%, and PASOK dropped a bit further down to 12.3%. Nea Dimokratia was then able to form a coalition government with PASOK and another smaller party, but the old two-party system was thoroughly broken, and SYRIZA had by now cemented its place as the main opposition party. As the Memorandum policies tore apart Greek livelihoods, it seemed only a matter of time before the Left would win the next election.

That time arrived two and a half years later. In January 2015, after relentlessly campaigning against the Memorandum Agreements (there were three by now), Alexis Tsipras became the first Prime Minister to come from the traditional Left in Greek history. SYRIZA won the election with 36.3% of the vote and formed a coalition government with an ‘anti-Memorandum’ populist right wing party. Meanwhile, PASOK’s share collapsed to 4.7%.

Negotiations with the Troika

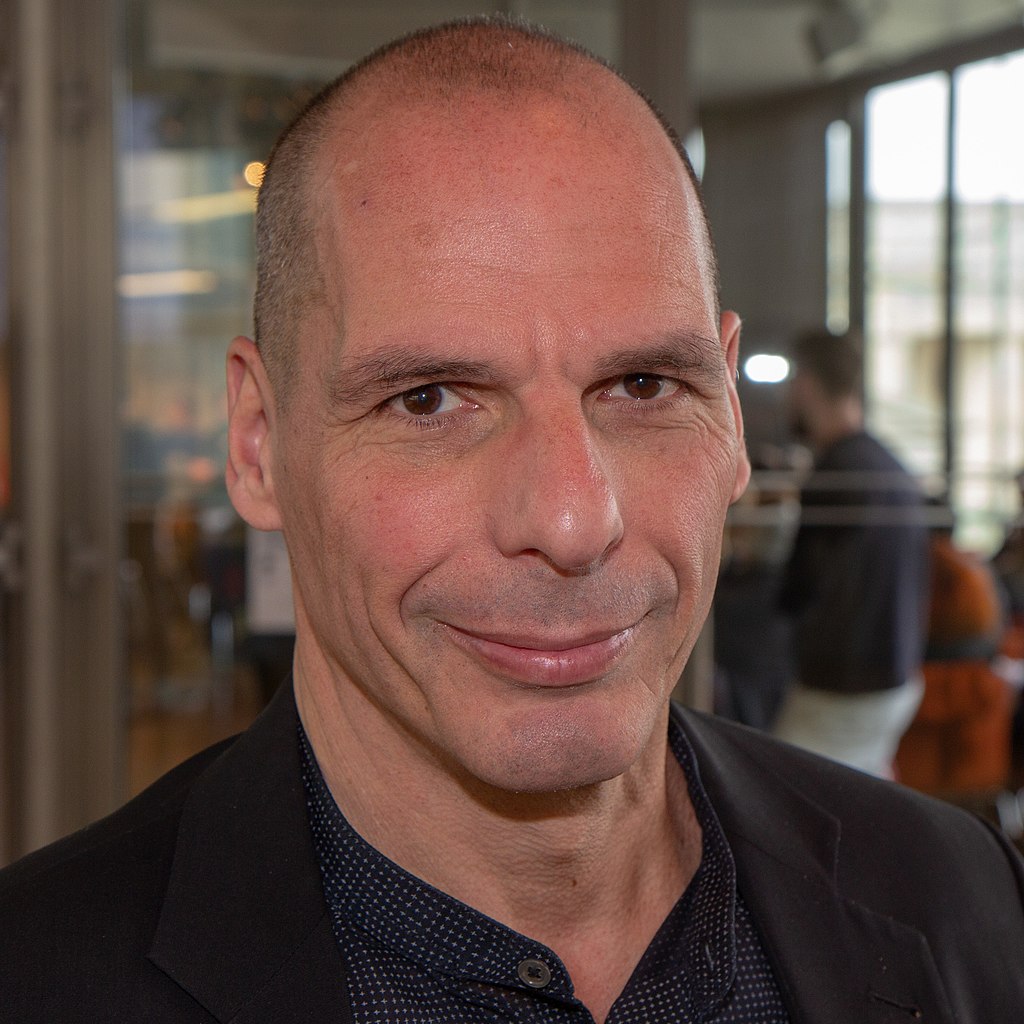

The rest is history as we say in these cases, implying that most people remember at least the gist of what happened. SYRIZA went on to try and renegotiate the Memorandum with the so-called ‘Troika’ (European Commission, European Central Bank and International Monetary Fund). This effort was spearheaded by the eccentric economy professor Yanis Varoufakis, but stumbled upon the unrelenting determination of people such as Germany’s Minister of Economy at the time, Wolfgang Schäuble, to create an emphatic cautionary tale, by steamrolling Greece and even pursuing its expulsion from the Euro currency, a scenario which became known as “Grexit” at the time.

After six months of futile negotiations, on June 27, Alexis Tsipras decided to call a referendum on the agreement proposal presented by Jean-Claude Juncker on behalf of the ‘Institutions’ – which was simply a new label used for the Troika, a shift in semantics, arguably, of very little substance.

This referendum was never meant to be about Greece leaving the Eurozone and technically the question was not that, but it was widely presented as such, inside and outside Greece. It was perceived that if the Greeks voted ‘NO,’ that would lead to a head on collision with the EU, which would in turn end up in Grexit. This might have been the case indeed, if the SYRIZA government had held its hard line to the end.

On July 5, 2015, Greek voters overwhelmingly rejected the Troika proposal, with NO getting 61.3% of the vote, while YES received 38.7%. The next day, Yanis Varoufakis, who was a proponent of the hard line, filed his resignation from the Economic Ministry, as requested by Alexis Tsipras. This was meant to be seen as a token of good will towards the Institutions, but was mostly interpreted as a first step towards capitulation.

On July 12, after seventeen hours of negotiations, Greece came to an agreement with the Institutions, effectively signing a new Memorandum, with similarly harsh terms to the ones rejected in the Referendum, leaving many in Greece, and around the world, to wonder, to this day, what was the point of it. Essentially, the SYRIZA government and Alexis Tsipras had completely capitulated.

To be fair, this was done under immense pressure from the Institutions, particularly the EU ones, whose stance during the final stage of the negotiations amounted to a threat of total economic war. On the other hand, however, that stance was entirely foreseeable.

Yanis Varoufakis.

The First Split

After the capitulation came SYRIZA’s first split. On July 15, the first part of the new Memorandum was voted into law by the Parliament, thanks to the votes of opposition MPs, after 32 of SYRIZA’s MPs voted against it, including three Ministers. Others had already resigned.

Alexis Tsipras was then compelled to call an early election, which was held on September 20. He managed to win this election again with 35.5% of the vote, and form a coalition government with the same right wing populist party. Importantly, a new party formed by the dissidents from SYRIZA, who voted against the memorandum, didn’t manage to get more than 3% of the vote and was left without parliamentary representation.

SYRIZA was able to snatch victory in that second election of 2015, as the wrath of the public against the old political establishment was still warm, but also after getting rid of its ‘far-’Left faction, which was more open to examining Grexit scenarios. Thus, the party had effectively made its first pivot towards the political centre, notably retaining the bulk of the former PASOK voters that brought it into government.

At the same time, however, the glass had cracked, as the popular Greek expression goes. The party had received a massive dent to its credibility, which had not matured sufficiently to find expression in those very early elections. The path forward though, was going be one of gradual, albeit constant attrition.

Thereafter, SYRIZA’s rule was full of challenges, imposed by the memorandum, which finally reached a point of completion in 2018, although many (Yanis Varoufakis for instance) would argue that there are still commitments in place that bind Greece for decades to come. Regardless, Alexis Tsipras celebrated what he proclaimed to be the end of the memorandum era and tried to present that as a successful outcome from his administration. His time in office, however, was heavily tainted by the terrible tragedy in Mati, on July 23, 2018, where a wildfire claimed the lives of 102 citizens, in what was seen as a gigantic failure of crisis management by the State.

On July 7, 2019, SYRIZA lost the election, but not as badly as many had anticipated. Nea Dimokratia won decisively with 39.8% of the vote, and was able to form a single-party government, but SYRIZA came in second with 31.5%, thus maintaining the status quo of it being the other major party in the new two-party system. At the same time though, PASOK had managed to regain some ground, coming in third place with 8.1%.

After the defeat, Tsipras announced there would be a reorganization of the party, with more involvement, and also an increase in membership. He therefore presented plans that would make the party more inclusive, which also meant politically more inclusive, so that it would represent the whole spectrum of the Left to Centre-Left and would be appealing to the middle class, which had been heavily taxed during his administration. This was met with some resistance and begrudgery from a big section of the rank and file, namely the old guard of the traditional New Left.

The leader of Nea Dimokratia, Kyriakos Mitsotakis, became the new Prime Minister, continuing a Greek tradition of dynastic families dominating politics, as his father had been Prime Minister in the early nineties. His administration was riddled with numerous scandals and fiascoes and was also seen as autocratic, with brazen disregard for the Rule of Law. Many would argue that it is the most radical right wing administration the counrty has witnessed since the military dictatorship (1967-1974).

It was also tainted by a terrible tragedy, the train collision at Tempi, which claimed the lives of fifty-seven citizens, mostly young people. Therefore, it came as a massive surprise, including to the politicians and voters of Nea Dimokratia, that in the recent elections they won by an unprecedented landslide, while SYRIZA as the main opposition suffered one of the most comprehensive defeats in the history of the Greek parliament. Twice!

On May 21, 2023, Nea Dimokratia won the elections with 40.8% of the vote, a 1% increase on 2019, crushing SYRIZA with a double score, as they came in second with 20.1%. PASOK regained some more ground, establishing itself in third place by raising its share to 11.5%, and has since been considered to be back in the game. These elections could not easily produce a government, as they were held by the ‘simple proportional’ system, that was voted into law by SYRIZA during its rule.

According to many pundits, this was one of SYRIZA’s most critical failures. They legislated for the simple proportional system – a long-standing demand of the Left – but they were unable to navigate its consequences. This system doesn’t give any extra seats to the first party, so it makes it almost mandatory to form a coalition government with other parties.

SYRIZA was unable to convince the electorate that they would be able to secure such a coalition agreement, as they confronted the stern refusal of PASOK to leave that window open, as well as the Varoufakis party and the Communist party. The right-wing populist party that had been their partner in government before, didn’t even exist by then. So, isolated by the rest of the Left, they ended up falling victim to their own law, while at the same time creating the impression that such left-wing ideas sound more democratic in theory, but are dysfunctional in practice.

Nea Dimokratia wanted to achieve a single party government and seeing this was entirely within their reach, they instantly opted for a repeat election, which would be held with the old system which provides an up to fifty seat bonus to the party in first place. Nea Dimokratia had already voted this ‘boosted proportional’ system back into law in 2020, but when the election system changes, it comes into effect after the next election.

The campaign period was very short. The repeat elections were to be held over just a month. The results of the May elections had taken absolutely everyone by surprise. No polling was able to predict this. In fact, it was the first time anyone could remember in a long where the polling was not seriously favouring the right wing faction.

The shock was numbing for SYRIZA politicians and supporters. There was very little time and very low morale to be able to make any drastic changes for a more effective campaign. A second electoral humiliation seemed inevitable, and the main sentiment was fear that the second defeat would be even worse. And it was.

On June 25, 2023, Nea Dimokratia won with 40.6% of the vote, and formed a single party government, while SYRIZA lost even more ground, getting 17.8%. PASOK made very little gains, coming in third with 11.8%, but found itself closer to second place, affirming its comeback, after sinking into near oblivion eight years earlier.

President Joe Biden greets Greek Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis, Monday, May 16, 2022, in the Oval Office. (Official White House Photo by Adam Schultz)

Resignation of Alexis Tsipiras

After such an unmitigated disaster, it was inevitable that Alexis Tsipras should resign. He didn’t do so immediately, but a few days later, fueling conspiracy theories down the line.

Many supporters and colleagues tried to dissuade him, as it seemed unthinkable to replace him. He was the leader who drove the party from barely entering the parliament, to governing the country in the space of a few years. There was almost a cult of personality around him, which persists to this day among a broad section of left-wing voters. But no leader, no matter how historic, could bear the weight of what had just happened. So, on June 29, after being president of SYRIZA for fifteen years, Alexis Tsipras resigned, leaving the party in even further disarray.

An internal election was called to elect a new president. In July, four candidacies were submitted to the party Central Committee. These candidates represented different fractions within SYRIZA and the different approaches within the reorganization and the political direction of the party in the future.

Efklidis Tsakalotos, a former minister of the economy, was the candidate representing the old guard of the New Left, the generation that broke away from the Communist Party after the split of 1968. They had been pushing back for years against the agenda of pivoting further to the centre.

Representing the aforementioned centrist agenda was Nikos Papas, the former right-hand man to Alexis Tsipras, a former Minister for State, as well as Minister of Digital Policy, Telecommunications and Media. He is probably the most Machiavellian figure to emerge out of the Greek Left in several decades.

Between the two, politically, was a female politician that had risen to prominence within SYRIZA’s rank and file. Well-educated, rather moderate, but still representing the Left, Effie Achtsioglou is a former Minister of Labor, Social Security and Social Solidarity. She became the clear favorite to win the race.

Finally, a fourth candidate entered the fray as a dark horse – the seventy-seven-year-old Stefanos Tzoumakas, a former minister from the old PASOK administration of the 1980s, which had been much more left-leaning in policies than the PASOK of the mid-1990.

This internal election was scheduled to take place in September, meaning most of the campaigning would take place in the summer. Given that timing, on top of the destroyed morale from the preceding national election, the trajectory of the campaign seemed very idle and ultimately grim. There was no hype, no discussions, no passionate political argumentation, no media coverage, and not much interest if truth be told.

It felt as if hardly anyone cared about this election and there was serious concern that the whole process would take place very quietly, with Effie Achtsioglou being elected after an embarrassingly low turn-out, undermining her position from the beginning. Her victory was considered a certainty, as polling showed her to be very far ahead of the other three candidates.

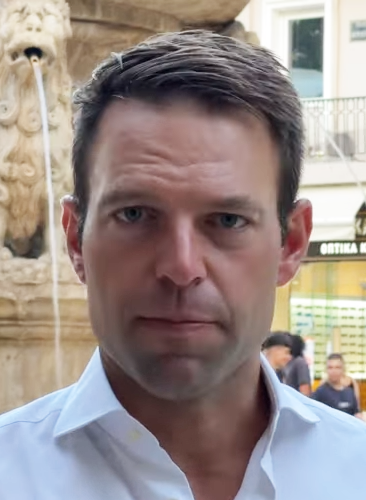

Stefanos Kasselakis.

A Twist in the Tale

Then out of the blue in late August, a massive twist in the tale occurred. It took most people by surprise, but there had been assiduous preparations going on under the radar during SYRIZA’s idle summer of wound licking. A young, rich and handsome, gay Greek businessman who had been a resident of the USA since adolescence –previously working for Goldman Sachs and being a ship owner – who had only very, very recently joined the party, started getting a lot of traction on social media in the last days of August, making TikTok-like videos with political statements.

Rumors started spreading among SYRIZA supporters that an almost messianic figure had come from America to save the party. It escalated very quickly until finally, on August 29, ten days before the internal elections were scheduled to take place, Stefanos Kasselakis announced his candidacy to the Greek people by means of a viral video (and also with much less fanfare a few days later, through the official party process).

Έχω επίγνωση ότι δε διαθέτω κομματική προϋπηρεσία. Η προϋπηρεσία μου είναι στην εργασία, στην κοινωνική ζωή. Η υποψηφιότητα που τώρα θέτω δείχνει έναν άλλο δρόμο: Από την κοινωνία και για την κοινωνία.

Αρκετές γενιές χάθηκαν. Είναι ώρα να φτιάξουμε το Ελληνικό Όνειρο που τόσο… pic.twitter.com/cUejwTOany— Stefanos Kasselakis – Στέφανος Κασσελάκης (@skasselakis) August 29, 2023

The stagnant waters of the internal election suddenly turned into a full-blown tempest and took the spotlight of media coverage, even monopolizing the headlines for many days. This guy who had seemingly appeared out of nowhere, was exclaiming that he was the one who could beat Mitsotakis, and appeared to pose the only credible threat to Efi Achtsiolou after the resignation of Alexis Tsipras.

Most of the party cadre were taken aback, especially as, despite his enormous clout, he didn’t seem to have the support of any of the party’s prominent MP’s. Except one that is. Pavlos Polakis has been a very particular character within SYRIZA. Known for his abrupt manners, coarse rhetoric and polemic stance against the Mitsotakis administration, he was passionately loved by a significant section of the party’s supporters and fiercely hated by his political opponents. Often labeled ‘toxic’ by his opponents, a label which may have even appealed to some of his own supporters.

Polakis had previously disagreed with the decisions around the process of succession back in July, and, although he was widely expected to, had not submit a candidacy for the internal election. Now it seemed that he had figured out another plan altogether.

Other than their common Cretan ancestry, the somewhat aristocratic Kasselakis and Polakis seemed a very odd couple. And yet, from the beginning, Kasselakis was being labeled ‘the Polakis candidate.’ Among the thirty members of the central committee that signed endorsements for Kasselakis’ submission of candidacy, there was only two current and six former MPs. Except Polakis, most of them were largely unknown to the general public.

The rank and file of the party was instantly rather suspicious of the American-bred newcomer, his dramatic entrance and his precipitous rise in popularity. The other candidates and their supporters within the party also quickly expressed their reservations. Except Nikos Pappas.

In retrospect, it’s tempting to think that he never seemed as fazed as everyone else. For one thing, Kasselakis soon made it clear that he represented the ‘pivot to the Center, so we can govern again’ line, with a twist of American modernity. He spoke about ‘the Greek dream,’ the ‘modern, patriotic Left,’ ‘healthy entrepreneurship’ and other rather centrist-sounding rhetoric. Indeed, he had already written an article back in July, calling for SYRIZA to become a Greek version of the Democratic Party of the USA. But his wildest statements were yet to come.

After the initial shock, and the realization that this guy was not a joke, but was in fact, getting significant traction among the desperate and disillusioned SYRIZA voters, the criticism began, and got gradually harsher.

The old guard, the remaining left wing of the (increasingly less) left-wing party, was the first and loudest to react. Tsakalotos and his supporters labeled him ‘a phenomenon of meta-politics,’ ‘TikTok politician’ and accused him of wanting to abolish the left-wing character of the party.

Meanwhile, various revelations about Kasselakis’ past started circulating, fueling resentment against him among the traditional Left. Articles and speeches by him were uncovered from no more than a decade before, where he expressed openly neoliberal views, even praising Mitsotakis specifically.

Stefanos Tzoumakas completely unloaded against him with raging rhetoric, but he had very little influence, as he was nothing more than a cult figure in the race. Effie Achtsioglou was more reserved in expressing her doubts around his suitability, albeit she eventually did. Nikos Pappas on the other hand, merely welcomed him in the race, saying that new candidacies would bring more attention to the race.

He got that right for sure. This election had hardly even making it into the news, but after Kasselakis’ appearance, his candidacy became a primary focus of the news media. This was only interrupted by the catastrophic flooding in Thessalia, which was also a reason to delay the first round of the election by one week, to September 17, thus giving Kasselakis more time to unfold his communication strategy.

Effie Achtsioglou.

Social Media

What played a critical and rather shady role in this whole affair was social media. It had been mostly word of mouth and social media rumours among members throughout the summer, that many prominent party cadre and MPs had been undermining Tsipras in various ways and had invested in his defeat in order to replace him, cancel his plans for broadening the political framework of the party towards the centre and take back control of the party. This was especially directed at the traditional Left faction, coming mostly, but not exclusively, from former PASOK supporters that had joined the party at the time of the Memorandum.

There was also, however, apart from the informal channels, a certain digital tabloid media outlet, called Periodista, that consistently peddled that precise narrative, sometimes even boasting ‘you’re not going to read this anywhere else.’ The owner and chief editor of Periodista, Dimitris Bekiaris, is widely considered to be a stooge of Nikos Pappas, who had, among other things, given him an enviable position in the public service under his Ministry, back in 2015.

In September 2023, these rumors and conspiracy theories spiraled out of control on social media, with very well known and prolific SYRIZA twitter accounts raging against the ‘nomenclature’ in favor of Kasselakis. Many people with inside knowledge of the party’s higher echelons, would swear, mostly in private, that the informal communication apparatus of SYRIZA in social media had always been controlled by Nikos Pappas.

This rumor mill peaked just a few hours before the first round of the election.

On Saturday, midnight, September 16, Nikos Manesiotis, a journalist largely unknown to most people until that point, but highly controversial since then, published an article, where he claimed that Efi Achtsioglou sent an sms to Alexis Tsipras the night of the second defeat pushing him to resign.

Very quick to reproduce that article was Dimitris Bekiaris, through his tabloid. So quick in fact, that either by a typing error or some dubious miracle, the article appears until today to have been reproduced before it was published in the original Manesiotis outlet. The aforementioned SYRIZA twitter accounts picked it up and waved it like a pitchfork. The news spread like wildfire and became the headline of the day. The day of the election that is.

Kasselakis won the first round with 44.9%, gaining a serious advantage for the second round against Achtsioglou who got 36.2%. At the lower end of the same clash, Tsakalotos came in third with 8.8%, followed closely by Pappas who got 8.6%. Tzoumakas got 1.3%.

The next day Pappas got behind Kasselakis and Tsakalotos behind Achtsioglou.

The two camps were set for the second round that would come after one week.

On September 19, one of the closest associates of Alexis Tsipras, Thanasis Karteros, wrote an article in Avgi, the official SYRIZA newspaper, where he completely dispelled the sms conspiracy theory, using notably scathing language. describing: ‘Lies, provocations, revelations from the intestines about malicious sms, that neither the receiver, nor anyone else was aware of, until we were enlightened by the rats of the internet.’

But it was too late. The election campaign was muddied and any notion of the truth had been relativised by the proliferation of incessant trolling polemic in social media.

Kasselakis Victorious

On Sunday, September 24, Stefanos Kasselakis won the second round with 56.7% of the vote, against 43.3% for Efi Achtsioglou and a new day dawned for the Greek Left. A pretty grim day so far. To be fair, Kasselakis appeared to make an effort to reconcile the different factions of the party, but the chasm was too deep. He immediately offered Achtsioglou any position she might want in the new reality of the party. Achtsioglou declined claiming she was ‘too exhausted’ to take on big responsibilities, which, admittedly sounded disingenuous, given she was contesting for the leadership of the party until the day before.

But the most acrimony kept coming from the Tsakalotos faction of the old guard. They were particularly triggered by Kasselakis’s speech on October 10 at SEV, the Union of Greek Industrialists, where he introduced himself as a left-wing businessman and made remarks hardly distinguishable from a ‘trickle down’ narrative. He stated that ‘SYRIZA is passing to the next stage of its historical trajectory, where it does not demonize the word ‘capital,’ but sees it as a useful tool for prosperity.’ Going even further, he suggested that they should offer stock options to employees, something already previously proposed by Kyriakos Mitsotakis.

From that day on, it was a mere countdown before the first split. Or rather, the first stage of a two-stage split. A month later, on November 12, the Tsakalotos faction, including the majority of the prominent historical cadre of the old guard, announced its departure from SYRIZA with a strongly worded text of resignation. Two MPs and 45 members of the Central Committee left the party.

This had seemed inevitable for some time, and the supporters of the president didn’t appear very worried about it. It was seen by many of them, and definitely by the raging trolls on social media, as a politically hygienic purge, that would liberate the party from a burden holding it back. At the end of the day, they didn’t have enough MPs, or popular support, to create another party that could be competitive. The assumption was that they would soon be all but forgotten as a relic of the past. This had happened before and could be the case again, but the splitting was not complete yet.

Kasselakis and his entourage were hoping that they would merely get rid of the annoying, ideological old geezers, but keep the predominantly forty-something Achtsioglou faction within the party. But that was not how things turned out.

After his victory, Kasselakis became increasingly aggressive with those who he considered to be questioning his authority and were not keeping in line with his vision for the transformation of SYRIZA. He maintained a harder stance towards the Tsakalotos faction, which was expected to leave anyway, but his somewhat authoritarian style created discontent that spilled far beyond the old guard.

On November 23, 9 MPs and a total of fifty-seven party cadre from the Achtsioglou faction announced their departure from SYRIZA, stating in their text that ‘Stefanos Kasselakis was elected democratically. But his course is undemocratic.’

The nine MPs declared themselves independent, and as had been speculated over the days before, they joined the other two MPs from the Tsakalotos faction, so that they could reach the minimum threshold of ten MPs necessary in the Greek Parliament to form a ‘parliamentary group,’ and enjoy institutional status and representation.

Thus, the two-stage split was completed and a new party was founded, called Nea Aristera (New Left). Its name was meant to point at its historical ideological origins, but also project the idea of a new beginning. The new political force found itself with little time to build an apparatus before the European elections, but with a ready-to-go parliamentary group.

Quite belligerently, Kasselakis labeled the Achtsioglou faction and the new party ‘defectors,’ and raged against them for not surrendering their seats back to SYRIZA. Their usual response was that the SYRIZA they were elected to didn’t exist any longer, and the new ‘Kasselakis party,’ as they labeled it, was hardly even left-wing any more.

Suitability for Prime Minister?

As time passed, the consequences of the acrimonious split started registering in the opinion polls. After the Christmas break and the new year, poll after poll was showing SYRIZA’s electoral influence waning and PASOK making gradual gains, until several of them started showing SYRIZA in third place with a tendency to reach single digits. At the same time, Kasselakis performance in the question of ‘suitability for Prime Minister,’ was staggeringly low, reaching just 4% in one poll.

This became yet another cause of friction and nagging within the party, as a shimmering question arose in everyone’s mind: What happens if SYRIZA performs as miserably as the polls suggest in the European -elections? There was a lingering murmur that Kasselakis would have to resign in that eventuality.It was in that climate that the party was heading towards its convention in late February.

On February 17, five days before the convention which was set to take place February 22-25, Kasselakis took an initiative that created yet more turmoil. Completely circumventing every party organ, he used his personal social media to ask members to log in to the digital platform SYRIZA, in order to fill in a questionnaire, with a rather provocative content.

Questions included whether SYRIZA should change its name and symbol and as whether it should identify as Left or Center-Left. The remaining rank and file of the party went ballistic over this and called for an immediate meeting of the political bureau, where Kasselakis was expected to explain his actions.

Kasselakis did not, however, attend the meeting on February 19, as he was in London. Instead, he sent a letter which left the assembly of the political bureau unimpressed, and which was characterized as patronizing. Party cadre who had supported him in the internal elections were now openly expressing their discontent about his behavior and even mentioning the possibility of replacing him.

Notably, Pavlos Polakis and Nikos Pappas both expressed criticism during that meeting. After the fallout of a two-fold split, the new president was once again being doubted and his leadership questioned. In response to that he made an unequivocal statement in London, during an event in LSE, that same evening, three days before the convention. After being asked if he would consider resigning if he lost in the European elections by more than twenty percentage points, he answered with a simple, unequivocal ‘No.’

The following day, Kasselakis returned to Athens and attended the second meeting of the political bureau, giving the members an ultimatum. He refused to be judged by the results of the European elections in June and asked the attendees to commit that they would not challenge his leadership for the next three years – all the way to the next national elections – regardless of how the party performed in June. Otherwise, he would call for another internal election. According to reports the response he got was that nobody can receive such a blank check and that this was an unprecedented request.

The next day, on the eve of the convention, some in the media described the meeting of the political bureau as a defeat for the new president, as he didn’t get the commitment he had asked for (only three members supported that request) and had to walk back his threat of an internal election. In any case there seemed to be some kind of compromise reached that members hoped would make the convention less contentious than it was projected to be with that last minute escalation. But another massive plot twist was about to take everyone aback and light a fire under the convention.

Dramatic Intervention

February 22, was the first day of the convention. It was set to begin at 6pm, with Stefanos Kasselakis giving his introductory speech at 7pm. At 4.48pm, Alexis Tsipras broke several months of silence and neutrality with an emphatic intervention that he posted on social media. In it, he passed critical judgment on almost all the protagonists.

Regarding those who had left to form Nea Aristera he wrote: ‘The defeated of the internal elections already left the party, because they lost the fight for its leadership. Not concerned with this fragmentation, the one who wins is our political opponent.’ Of Kasselakis he said: ‘The winner is reportedly asking for a three year blank check, regardless of the result of the European elections. Thus projecting an anticipation of electoral failure and also not caring about its consequences.’ Finally, towards unnamed plotters, he said: ‘While others disagree behind the scenes, but are quietly waiting for the electoral failure to come, so they can pin it on him. Not caring about what that would mean for the party and the country.’

Most importantly though, he brought back the internal election scenario, saying that Kasselakis was right to bring up the issue of his leadership being questioned, but advised him ‘to seek a vote of confidence, not from the political bureau, but from those who made him president.’ Despite the omni-directional criticism, Tsipras’ intervention was mostly interpreted by media pundits as an attack on Kasselakis. Not just in terms of what he said, but also given the timing. The text was posted without prior notice, just over two hours before Kasselakis’ opening speech. One can only imagine the panic and frenzy of his speechwriters, having to adapt to that at the very last minute.

The new president picked up the glove thrown by the former president and delivered a fiery opening speech at the convention. His passionate p0erformance was likened by some commentators to a television evangelist sermon. He spoke away from the podium, using a teleprompter, often addressing the crowd directly, which was overwhelmingly on his side. He finished his speech shouting ‘Find me an opponent and let’s go!’ proclaiming an internal election for president, seemingly ignoring that it wasn’t his decision to make, and he could only submit it as a proposal for the convention to ratify. Which it didn’t.

But there was quite a roller-coaster before getting to that point. The first evening of the convention was promising more heated confrontation, and definitely a lot of behind-the-scenes commotion. Late into that same night there was, reportedly, a meeting between eight prominent SYRIZA cadre, to discuss the rapid developments. Nikos Pappas was one of the people present.

The main topic of this dinner meeting was which candidate would stand against Kasselakis, after his flamboyant challenge. The meeting decided to call on Olga Gerovasili, a former minister, government spokesperson, vice-president of the parliament and a very close associate of Alexis Tsipras, to be the new president’s opponent. This stand-off, however, would be seen as a proxy clash between Kasselakis and Tsipras, something that would be likely to tear the party completely apart.

The next day, Olga Gerovasili had a series of meetings with many key figures among the rank and file. Her name was already all over the media until finally on February 24, the third day of the convention she announced her candidacy, before loud booing from the crowd, that forced the facilitator of the convention and even Kasselakis himself to intervene to stop the heckling.

What ensued was an unprecedented back and forth, impromptu debate between Kasselakis and Gerovasili, that continued the following morning – the final day of the convention. There was a strong disagreement about the procedure and the date of the proposed election that heated the atmosphere even further, as two different proposals were submitted by the two opposing sides.

As more and more of the people attending were agonizingly realizing that there is a clear and present danger of yet another split, perhaps even more acrimonious than the previous ones, Kasselakis and Gerovasili started calling on each other to stand down, in a bizarre blame game that seemed to reach an impasse.

The future of the party was hanging on a thread, until the final plot twist occurred that provided a way out by means of vague compromise. Three prominent SYRIZA cadre submitted a carefully worded proposal to the convention. Its main point was to reject the proclamation of an internal election, confirm confidence to the president and go forth united to the battles ahead ‘the first one being that of the European elections.’

The effort was led by Sokratis Famelos, the leader of SYRIZA’s parliamentary group and one of the few remaining people who enjoy widespread respect within the party. Along with him was Giorgos Tsipras (a cousin of Alexis Tsipras), who had supported Kasselakis in the previous internal elections. The third one was Nikos Pappas.

If this proposal were to be voted on, the other two would automatically become redundant. It gained enormous traction very quickly and easily passed by a large majority among the 5.000 representatives that were present. There was a general sense of relief, mixed with a realization of damage sustained, as if everyone had managed to run out of a crumbling building during an earthquake. The next day was not going to be easy, but the worst outcome had been averted, although the party had (barely) survived.

Olga Gerovasili.

Winners and Losers?

There was a lot of discussion in the media after the convention, about who were the winners and losers. As much as there were different interpretations to that, the common denominator was SYRIZA had lost overall. Some pundits described it as a lose-lose situation for everyone involved. The only one who came out unscathed, as the one who, almost literally, saved the day, was Sokratis Famelos.

Kasselakis and his team tried hard to present it as a victory for their side, but the fact of the matter is that they didn’t get any guarantee that the president will remain in his place regardless of the outcome of the European elections. Also, his proposal, which he insisted on until the last moment was ultimately rejected by the convention in favor of the Famelos one. Furthermore, his rather erratic behavior at many points during the convention might have received a lot of applause from the attendees, but these people are not representative of the population at large. His overall image among the broader public definitely sustained damage.

Olga Gerovasili also had her image tainted, as she was repeatedly booed by members of her own party on prime time national television. Furthermore, she appeared rather weak, after preferring to avoid the head on collision with Kasselakis. As for Alexis Tsipras, he also undoubtedly had his status wrinkled, as his own proposal was also rejected by the convention and his intervention was seen by many as making things worse. Many pundits describe him as the main loser of this whole debacle. Some other pundits, however, speculate that his main purpose was to distance himself from Kasselakis for future reference.

All these plights of the Greek Left, make one wonder to what extent SYRIZA ever really stood a chance. Its rise to power was a product of a very specific and very turbulent historical context when for a moment, everything that was solid was melting into air. They saw a massive void in the previously galvanized political establishment and jumped excitedly in to fill it. They grabbed a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity, but ultimately left the impression that they didn’t really know what they were getting into.

Their administration was suffocated and chastised by all the main powers of the Western world as soon as they got into office. They fought against them half-heartedly, without ever convincing anyone that they would be prepared for an ultimate showdown. And thus they had to succumb. All the back and forth and pointless drama made them look like amateurs who were hopelessly improvising. And once the fervor and turmoil that brought them into power subsided and became a bygone era, they struggled to find a road map to become a sustainable force for the long term.

Eventually, a majority of them internalized the idea that the party wouldn’t be able to govern again as itself and had to change its appearance and even its political identity. The tragic irony is that this had already been happening, little by little over the previous years. But it seems they needed a more definitive and somewhat ceremonial manner to make a point that this is not any more the old SYRIZA of the 2015-2019 administration. No longer the Coalition of the Radical Left

that bites far more than it can chew, but a modern, moderate and patriotic party of professional politicians that know what they’re doing and can play the contemporary communication game just as well as the Mitsotakis gang.

Truth be told, that’s not been going too well either. However, while this article was being written SYRIZA has seen a slight recovery in the polls, which, coupled with the simultaneous stagnation or even small drop of PASOK in the same polls, has brought it back into second place, but still below their last national election results. But even if Kasselakis manages to overcome his very bad start and gain more ground in the polls, or even get a positive result in the European elections, SYRIZA as we knew it is gone.

In any case, the road ahead is a very difficult one for the Greek Left. Polling consistently shows the unchallenged domination of Nea Dimokratia under Mitsotakis. It seems extremely unlikely that any single party could defeat them, especially in a national election. A completely fragmented political spectrum of the centre-left is heading towards the European elections without any prospect of cooperation whatsoever. The assumption is that every force wants to maximize its electoral influence in June. Then, after the dust settles and there is a certain hierarchy established, there will be a gradual process of political fermentation (as we say in Greek) in order to form an anti-Mitsotakis front. But right now, this prospect seems light years away.

Feature Image: Syriza party chairman and former Prime Minister of Greece Alexis Tsipras in 2012.