Even if these operations are shocking revelations to those who have a romantic notion of the past then the risk of their disillusionment is worth the price of finally exposing the hypocrisy of those in the establishment who rest self-righteously on the rewards of those who in yesteryear’s freedom struggle made the supreme sacrifice.

Sinn Féin Pamphlet, The Good Old IRA, 1985.

It’s fair to say we shouldn’t apply the same judgment to people of the past as we do to our contemporaries. Throughout history, men and women have been conditioned to live and think in ways quite alien to prevailing sensibilities. Looking back into pre-history, we find infanticide commonly practised by hunter-gatherer communities, probably to ensure collective survival.

Many Irish people in the 1930s supported either Fascism in Italy and Germany, or Communist Russia, without being acutely aware of what was happening under those regimes; let alone what would happen during World War II, and beyond.

At that point democracy seemed in global retreat, as a civilisation-defining war loomed between two rival systems, while the surviving democracies contended with a Great Depression that suggested an inherently dysfunctional capitalist system. A person might reasonably be attracted to a radical alternative, however horrifying these totalitarian systems may appear to us now.

Arguably the best did not lose their moral scruples – or democratic values – albeit they may have lost ‘all conviction,’ as Yeats anticipated in ‘The Second Coming’; indeed, he has been described as a fascist ‘fellow-traveller’ himself.

It begs the question: when does the past become a foreign country, where they do things differently? When do we stop judging people by the standards of today? At what point does a new era begin? Can a person even straddle two epochs?

For example, the Sinn Féin party that now stands on the brink of power in Ireland are commonly castigated for the conduct of the IRA during the Troubles in Northern Ireland. Yet few, if any, members of that party in Dáil Eireann actively participated in the Provisional IRA.

In contrast, the origin of Fine Gael, which emerged as a combination of Cumann na nGhaedhal, the Irish Centre Party and the National Guard, better known as the Blueshirts, in 1933, tends to be ignored, or even qualified.

O’Duffy leading a salute with the Blueshirts, December 1934.

Thus, Irish Times columnist Stephen Collins defines the Blueshirts as ‘best understood as para-fascists,’ which according to one source is ‘a larger category of regimes that adapted or aped ‘fascist’ formal and organizational features, but did not share the revolutionary ideological vision of genuine fascism.’

Such nuance might have been lost on General Eoin O’Duffy and his more earnest acolytes; albeit my own great-grandfather, John A. Costello – whose commitment to human rights made him an acceptable Taoiseach to former IRA chief of staff and leader of Clann na Poblachta Sean MacBride in the First Interparty Government of 1948 – injudiciously declared in 1934: ‘the Blackshirts were victorious in Italy and … the Hitler Shirts were victorious in Germany, as … the Blueshirts will be victorious in the Irish Free State.’

During periods of crisis even decent people can be carried along by waves of hysteria that cause civil liberties and common decency to be cast aside. A famous 2003 documentary ‘The Fog of War’ features former Defense Secretary Robert McNamara attempting to rationalise the U.S. bombing campaign in South-East Asia. Our present era where we witness a Populist clamour for mandatory vaccination may, in time, be viewed as one such illiberal period.

A youth growing up in a Catholic, or Protestant, working class neighbourhood in Belfast during the 1970s might easily, and perhaps reasonably, have become involved in what we now define as terrorist organisations. That individual might even have committed awful terrible crimes in the Fog of War.

It is a very delicate question as to what point we should let bygones be bygones and allow even participants in a sectarian, or post-colonial, struggle to participate in government without being constantly reminded of their past. Fine Gael certainly had no problem going into government with Clann na Poblachta in 1948, despite the latter’s association with the Republican cause.

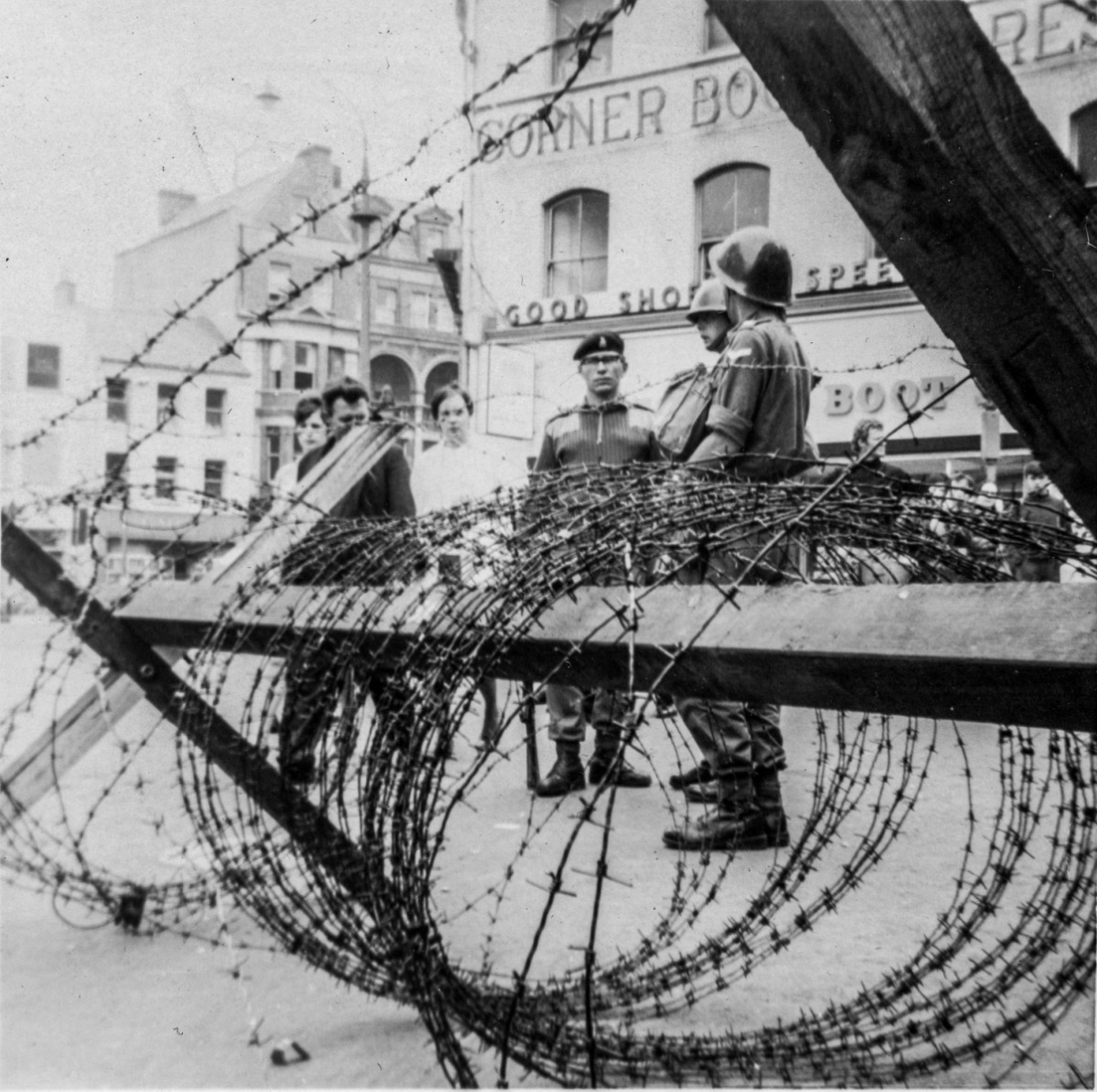

Belfast, 1969, Bob Quinn.

The Northern Ireland power-sharing executive represents an imperfect attempt to move on from the Troubles. It has at least diminished the level of politically motivated violence in that society.

This process was actively encouraged by successive Irish governments, especially through the mechanism of the 1985 Anglo-Irish Agreement, culminating in the participation of Sinn Féin in government.

Yet what we hear today in Ireland from the likes of Fintan O’Toole is that Sinn Féin somehow has a flawed pedigree, and must apologise, again and again. Frankly, it’s boring and inconsistent.

There is a larger question around how we represent political violence in an Era of Centenaries. The decision of Fine Gael and Fianna Fáil to enter into a coalition might be viewed favourably in terms of a definitive end to ‘tribal’ Civil War politics.

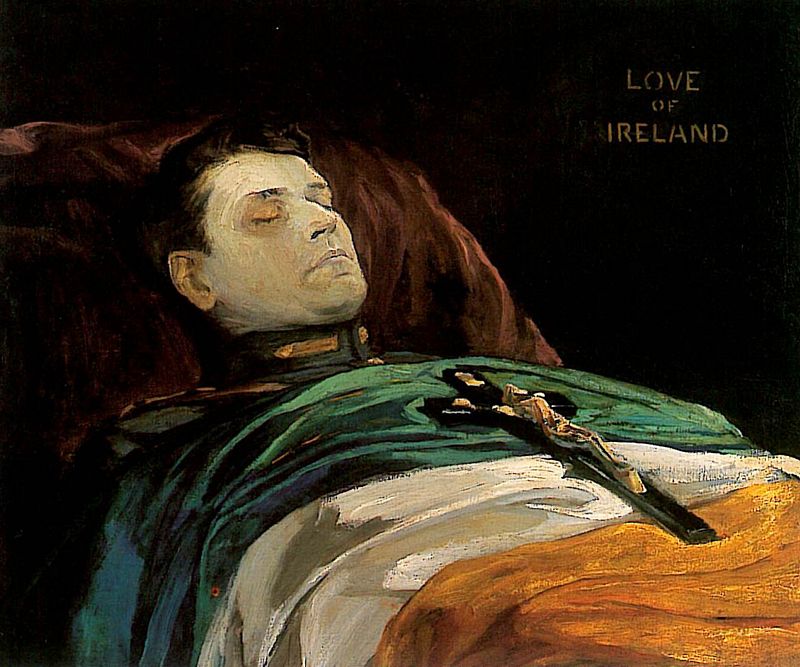

But what of the use of historical figures associated with those parties? In particular, is it appropriate for Fine Gael to remind the public of its association with Michael Collins, one of the great exponents of what supporters define as urban guerrilla warfare and detractors terrorism, or at least extra-judicial assassination?

Moreover, Collins participated in the Easter Rising led by Pádraig Pearse who said in 1913: ‘Bloodshed is a cleansing and sanctifying thing, and a nation which regards it as the final horror has lost its manhood … There are many things more horrible than bloodshed, and slavery is one of them.’

The shell of the G.P.O. on Sackville Street (later O’Connell Street), Dublin in the aftermath of the 1916 Rising.

Political violence was intrinsic to Pearse’s, and arguably Collins’s, approach to the birthing of the nation. They were men of their time, but were a faction within a faction that enjoyed less popular support than the Provisional IRA during the Northern Troubles.

Besides, while the British authorities in Ireland prior to independence were hardly a model of good government, they had at least distributed much of the land among peasant proprietors and developed reasonable infrastructure. Home Rule was on the statute book. It might be argued that 1916 made Partitition inevitable.

In contrast, the sectarian Unionist government – ‘a Protestant parliament for a Protestant people’ – in Northern Ireland was denying civil rights to Catholics, gerrymandering constituency boundaries and sponsoring the B Specials, a sectarian, quasi-military reserve special constable police force.

The Northern Troubles was a dark period in the history of the island, but to suggest those involved were, and are, inherently evil rather than, in most cases, products of historical forces, is lazy reasoning. Let’s put to bed the idea the Troubles disqualifies Sinn Féin’s participation in government for ever more, and move on to scrutinising the detail of their policies, in particular a failure to adopt a discernible position on the optimum response to COVID-19 in Ireland.

Featured Image: Michael Collins by John Lavery, 1922.