My wrist watch stops dead shortly after we arrive in Tangier (at 21:16 – 2/6/2022, to be precise), which is symbolically appropriate. Time runs differently in Joujouka, the rural village located some 110km south of here in the Rif Mountains, for which this urbane, noisy, historically cosmopolitan port city is on this occasion serving as a gateway. I’d been to Morocco once before, in 2013, when the fissures in our marriage were beginning to make themselves felt. For that reason, and others, I was then flying solo. Now here I am again, with J, bringing her on part of the pilgrimage I had made then, having separated and reunited in the interim, working through whatever it was we’d had to sort out, together and apart. This would be a shared experience. Love me, love my obsessions.

In his monumental history of the drone in music, Monolithic Undertow: In Search of Sonic Oblivion (2021), which ranges from vibrating sound waves at the exploding dawn of the universe to the stoner/doom/drone metal of bands like Sleep, Earth, Boris and Sunn O))) – via the choral chanting of Buddhist and Christian monks, Indian raga, free jazz improvisation, various indigenous folk traditions, Krautrock, contemporary classical and avant garde, and electronic experimentation (drone is not codified or confined by genre) – Harry Sword devotes an entire chapter to The Master Musicians of Joujouka, in which he writes:

A mystic Sufi sect … the Masters – members of the tribe Ahl Serif – produce a narcotic cacophony that hinges on frenetic tribal drums, gruff call and response chants and the screeching drone of multiple rhaita pipes. Playing a music unique to the village and passed from father to son, the Joujouka sound is unlike any other.They’ve been at it for centuries. William S. Burroughs (or was it Dr. Timothy Leary?, provenance is disputed) famously called them the ‘world’s only 4000-year-old rock’n’roll band’. Playing for up to twelve hours straight, musicians and audience alike entering a waking dreamscape, theirs is a brutal trip. Joujouka music is principally about healing, delirium and fertility.

The Masters entered western consciousness initially through the Beats in the 1950s, and then the 1960s counter culture. Paul and Jane Bowles, Burroughs and his Canadian painter pal Brion Gysin, had all taken up post-War residence in Tangier, with visits from Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, Gregory Corso and Peter Orlovsky, among others. In 1951, Bowles and Gysin attended a Sufi music festival in Sidi Kacem, a couple of hours from Tangier, with a painter from Joujouka they’d met in the city, Mohamed Hamri. When he heard the Masters, Gysin was enthralled, saying he wanted to listen to their music every day for the rest of his life. Bowles, while an avid archivist of Moroccan tribal music – he made over 250 field recordings on location, Alan Lomax-style – was less enamoured, finding the Masters’ music ‘too crude’, and the hardships of village life unseemly. Later, when Hamri took Gysin to Joujouka, the ex-pat discovered to his astonishment that the music he’d fallen in love with was played by Hamri’s uncles. Gysin and Hamri then opened a restaurant in Tangier, the infamous 1001 Nights, where members of the Masters became the house band. It was there that Burroughs first heard them.

When the Rolling Stones arrived in Tangier in 1967, seeking respite from the fallout of the Redlands drug bust and attendant media attention while awaiting trial, Hamri and Gysin met them and Hamri struck up a friendship with Brian Jones, the only Stone to stay behind for a longer, more immersive encounter with the culture. Hamri brought Jones to the village, where he too was overwhelmed by the Masters’ music. Ever the ethnomusicologist, the troubled musician returned in 1968 to make recordings, which eventually saw the light of day in 1971 on Brian Jones Presents the Pipes of Pan at Joujouka. Before his death in 1969, Brian had produced the album and prepared the cover, which brought the Masters’ music to a wider audience outside Morocco. Later, in January 1973, jazz musician Ornette Coleman and the Masters recorded together, with ‘Midnight Sunrise’ surfacing later on his album Dancing In My Head (1975). In 1980, The Masters played at Glastonbury, as part of a three-month tour which included a week’s residency at London’s Commonwealth Institute. They were at Glasto again in 2011, opening the festival on the Pyramid stage. They have since toured as far afield as Japan.

The Masters’ performances in their home place feature a dancer sewn into goatskins: he represents Bou Jeloud, a Pan-like figure, half-goat half-man. In the legend, Bou Jeloud gave an Ahl Serif ancestor the gift of flute music and bestowed fertility on the village every spring when he came out of his cave and danced. This is commemorated in the Joujouka festival, now held every June. In 2008 the Masters honoured the 40th Anniversary of Brian Jones’s influential recording by opening their annual Rite of Spring to outsiders. Since then the extended gathering has become an annual occurrence, attracting artists, filmmakers, musicians, writers and fans from around the world. As well as generating valuable global publicity, the boutique festival is an important economic factor in the life of Joujouka, which remains predominantly a working agricultural village. These guys are still primarily farmers, who have not turned pro.

The extended festival offers a unique opportunity to around fifty guests, on a first-come first-served basis, to spend three days with the Master Musicians. This small influx stay in the village with the Masters and their families as hosts, and experience the music in the place – set amid a spectacular landscape – where it originated. The Masters play non-stop each night for three or four hours, in a large three-sided, green-and-red tent at the madrasa. During the lazy afternoons, spontaneous jams break out. Tickets are limited because you lodge in family homes, enjoying breakfast with them, and partake of a communal evening feast in the madrasa, before the Masters get down to business. It may be more arduous to get to, as well as more expensive (although with transport from and to the railway station, plus full board and lodging included, it probably all works out fairly equitably in the end), but it sure beats hell out of the rough and tumble crowds at Electric Picnic.

J is an ’80s and ’90s indie pop and rock girl (just as I, to some extent, am that boy). These days her principal favourite listening is Bach’s concertos for harpsichord, the plinkity-plonkity predictable resolves of which grate on my nerves (although I do have a certain tolerance for some of his keyboard works for church organ, for example the Fugue in G minor, which at least occasionally utilise the harmonic possibilities of that instrument for dronish effects – even if the lauded composer can never quite help himself when it comes to showing off his considerable chops). Sitting at our table on a terrace overlooking the swimming pool in our well-appointed hotel, with the techno beats of synth pop booming from the nightclub downstairs, I wonder how she will take to Joujouka – the village, the people, and the all-enveloping drone?

The next morning we are sharing a taxi with Richie and Marek, two Joujouka veterans I met there on my last visit, bringing us to El Ksar El Kebir, the nearest town of any size to the remote village. From there, we join another local taxi to take us up to our weekend destination. Like any expedition of faith – religious, quasi-religious or secular – Joujouka inspires devotion. Muslims may be required to take the Hajj to Mecca only once in a lifetime, but many Joujouka heads – those who get it and realise this ritual is for them – wind up coming back every year. Richie, a Scottish guy living in Portsmouth, and Marek, from London, are two such. Later I will reunite with Phil, hugging like long lost brothers. He’s an American labour lawyer now married (to a woman he met in Joujouka) and relocated to Mallorca, who always appears on some rented, high-end 1000cc motorcycle, which he then takes off on when the festival is over on Monday mornings, lighting out for the High Atlas mountains and the desert beyond, getting to places inaccessible by car and bus, or even camel.

But as every good nostalgist should know, you can’t step into the same river twice. The lingering pandemic, which had made the brandishing of vaccination certs mandatory at airports and passport controls on our journey here, means that Covid-hesitancy has depleted the usual number of attendees. There are about twenty-five people here this year, rather than the full complement of fifty. While facilitating more intimacy, this in turn makes it slightly more difficult to get a spontaneous vibe going later in the evening. Add to this the news that the festival’s chief organiser will be absent this year, for personal reasons, and one of the main points of contact and social lubricants between the villagers and their guests is removed.

There are other notables missing: Miho Watanabe, the indefatigably humorous Japanese academic, musicologist and multi-instrumentalist, who has travelled to many remote corners of the world to discover more about diverse native musical forms of expression, but who keeps returning to Joujouka; and Stephen, Phil’s ex-Navy biker buddy, now some sort of recondite computer coder – if Phil can be formidably cerebral, Stephen is possessed of the imp of roguish madness which lets him share my absurdist sense of humour. On the previous occasion I also met Donal, London-Irish friend-of-friends, and purveyor of the Exploding Cinema club; and David, copywriter and author of numerous articles on the Beats, Lou Reed, and the Deià of Robert Graves. Then there was Paul, music magazine editor, and writer of books on Iggy Pop, David Bowie, and Brian Jones. So: interesting folks. I have since noticed that the Masters’ website, in advertising the 2023 festival, starts with the admission that: ‘After two years of absence and a small offering this year, The Master Musicians of Joujouka annual festival is back in 2023.’ Still, reduced is better than nothing – and there would surely be fresh encounters to be had.

Last time I was assigned the room in which Brian Jones purportedly stayed during his sojourn here (I’m sure they tell more than one guest that, every year). This time J and I are billeted in a smaller room in a house a little further afield from the madrasa. But at least it has a double bed (with a straw mattress), instead of reclining sofas all around the walls. Family homes here are built around a central shady courtyard with a well in the middle. There is no running water, and the toilet is the proverbial hole in the ground, a shower is buckets of water (heated if you are lucky) thrown over yourself. Electricity only arrived in the mid-’90s.

Sometimes I think I’m getting too old for this. Also, I fret over J’s adaptation to the Spartan conditions. But that’s before the music beings. There again, I have my misgivings about how she will respond to that, too.

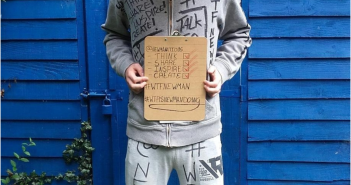

the definition of a gentleman..

Q: “What’s the definition of a gentleman?” A: “Someone who knows how to play the bagpipes, but doesn’t.” Corny, I know; but telling. Why do some people have such an aversion to many other iterations of the drone? I have heard the bagpipes described as one of the greatest instruments of torture ever invented. How can people be repulsed by the soothings of the uilleann pipes, or driven to distraction by sean-nós singing? Because of cultural associations that they would prefer to forget? Or are they genuinely put off by what they perceive as the sheer monotony of the sound, and its accompanying volume? More commonly than irritation, you hear people say they can’t stand drones because they find them boring. But drones are not boring – or else they are meant to be. A commercial device called the Mosquito discourages young people from loitering in shopping malls; it emits sounds in the 17.5-to-18.5-kilohertz range which, in general, only those under the age of twenty-five can hear. Drones are life’s underlying hum made more manifest. Louis MacNeice certainly thought so, in his jocose poetic lament for the decline of folk culture in the Western Hebrides, and indeed throughout Europe, ‘Bagpipe Music’ (1938). It’s no go the Yogi-Man, it’s no go Blavatsky/All we want is a bank balance and a bit of skirt in a taxi seeks to mimic the sound of the titular instrument.

The cultural dissemination of the drone is beautifully captured in Tony Gatlif’s wonderful documentary, Latcho Drom (Romani for ‘safe journey’) (1993) – perhaps the greatest film ever made about music and people. With scant dialogue and no voiceover, it presents scenes from Gypsy life, starting in Northern India, and working its way westward through Egypt, Turkey, Romania, Hungary, Slovakia, France and Spain. This is one route drone music took from the east, the other being through North Africa, Galicia, Britany, Cornwall, Wales and Scotland, to Ireland. It is a sound fundamentally at odds with the Anglo-Saxon conception of the world. Ethnomusicologist Joan Rimmer has suggested that the music of the Arab world, Southern Europe and Ireland are all linked, while folklorist Alan Lomax has said in interview: ‘I have long considered Ireland to be part of the Old Southern Mediterranean-Middle Eastern family of style that I call bardic – highly ornamented, free rhythmed, solo, or solo and string accompanied singing that support sophisticated and elaborate forms.’ Máirtín Ó Cadhain compared the singing style and dark physical appearance of Seosamh Ó hÉanaí to that of the Gitanos of Granada. This so-called ‘black Irish’ appearance is often attributed to Spanish Armada shipwrecks in the west of Ireland, or ancient trade routes from there with the Berbers. Film-maker Bob Quinn, in his Atlantean series, suggests a North African cultural connection, explaining the long physical distances between the cultures with the seafaring nature of the Connemara people. The musical connection has also been tenuously connected to the fact that the people of Connacht have a significant amount of ancient Berber or Tuareg DNA.

If you find drone music boring, or oppressive, or maddeningly distracting, I suggest that the fault may lie with you or your attitude to life, rather than with the drone. Your antipathy is explicable as rage against the unwanted. The trick is to turn this anger to your advantage, through

Metanoia, an Ancient Greek word (μετάνοια) meaning ‘changing one’s mind’, which refers to the process of experiencing a psychotic ‘breakdown’ and subsequent, positive psychological re-building or healing, a transformative change of heart, a transcendental conversion. Try focusing your attention, meditating, being ‘mindful’ as they say nowadays. In other words, whether squatting cross-legged on the ground, or whipping yourself into a frenzy of idiot dancing, don’t be afraid to enter the trance state. Listen to the voices within – until, one by one, they all disappear. Drones are as much about providing profound spiritual balm as they are a reminder of mournful, cosmic tedium. The choice is yours as to which way to go. The drone is what prayer should be – as Beckett has it in Malone Dies, the ‘last prayer, the true prayer at last, the one that asks for nothing.’ Om.

And that is about as historical/philosophical/spiritual as I’m going to get in droning on about drone.

Understandably, J had grown accustomed to hearing me rattle on about Joujouka, long before she decided to come here with me. Or so I had thought. Strangely, when I talk to her about it now, she says that I never said much except that I loved it, so she wasn’t sure what to expect. We had been living apart since the pandemic began, and neither of us had travelled on an aeroplane in over two years, so there was appreciable anxiety and hesitation around the trip, on both our parts. There was more at stake than just a holiday.

She makes friends with the family we are staying with, especially the teenage daughter of the house, Selma, who begins teaching her Arabic. Selma’s father is a French language teacher, and works in another town. Most Joujoukans of working age have migrated to Tangier or Chefchaouen, sometimes visiting for weekends, leaving a preponderance of the very young and the very old in the village. Selma spends a lot of time with her grandparents. As for the status of women, like the urban/rural divide in any country, there is more freedom and equality to be had in the cities, while traditional roles still obtain in the countryside. Selma will not make her life here.

Slowly, J is becoming more like her old self again. After a number of serious health issues, and being cooped up for lockdown, caring for her dying father, she is impressed by the way people here ‘just let things be, how happy they are with little’. This is what she remembers about being there:

Being with you again. The well in the middle of the farm. The great, fresh food. The green canopy. The hole to pee in. Taking my shoes off outside our room. The chickens outside. Donkeys, goats and chickens wandering around and the large village square. The walk to the music. The dust on the road. The heat. The trance of the music. The sweet, sweet mint tea. The talk around the table. The Goat Auntie – her lovely smile (a reference to Nadia, a Copenhagen-based Lithuanian pianist, who came with her aunt, a former concert violinist grown frustrated with orchestra politics, who now breeds goats – thus amalgamating two good personal reasons for being in Joujouka). Feeling shy. Feeling out of condition. The great walk to the cave. The music. The language barriers. The dancing. The strange day when I was blessed. The Japanese dancing. The long, colourful djellabas.

Ironically, given the Dionysian intensity and volume of the Masters’ sound, and the frenetic movements or trance states which it induces, this music is believed to have healing powers to cure instances of insanity. Legend has it that in the fifteenth century the Sufi mystic saint Sidi Achmed Sheikh, the ‘healer of disturbed minds’ who brought Islam to the surrounding area, arrived in the village and bestowed the ability to heal manifestations of madness on this group of local musicians, in return for which he was given the gift of their music. The village is his resting place. For centuries visitors have peregrinated to his tomb here to seek cures for mental illness. The musicians are said to be blessed by baraka, the spiritual power of the saint, and people also seek them out in the hope that they might partake of it. I’m as cynical as the next person when it comes to Rousseauan idealisations of the Noble Savage, and am fully aware of Edward Said’s critique of western Orientalism. Perhaps the salutary properties of this supposed baraka transmitted through the Masters’ music is a load of superstitious codswallop after all – but I’d still rather go to Joujouka seeking a cure for anxiety, depression, neurosis or psychosis, than to any psychiatrist from the so-called ‘developed world’. The experience of hearing the Master’s music live is indubitably preferable to undergoing a course of electro-convulsive therapy, and undoubtedly no more or less efficacious.

Talking to me now, J concludes: ‘Would I go again? Not sure – time is short, perhaps I’d like to try other places, other experiences. Compared to how you said it would be, it surpassed it. Joujouka was more primitive than I imagined, but Morocco more modern. You were right about an out of this world experience. Thank you for taking me.’

J is Scottish, and grows wistful when she hears bagpipe music: I knew she’d get Joujouka, and its ecstatically healing drone.

Believers undertake pilgrimages all the time, be it holy expeditions to Marian apparition sites such as Lourdes, Fatima, Medjugorje, or our own Knock (a destination to which my devout father, who was unquestioningly and without any trace of scepticism well into this stuff, organised an annual busman’s outing), or the religious journey which provides the backdrop for Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, or the bereaved who traipse the Camino to Santiago de Compostela in Galicia. My own parents’ idea of a summer holiday was the parish pilgrimage to Rome, Assisi and Loreto (they never quite had the wherewithal to make it to the Holy Land), a trip sixteen-year-old me declined to share with them, understandably not fancying a week or two in pullman coaches with the blue-rinse set, shepherded by the local dog-collared men-in-black. Better to remain at home, and have a ‘free house’ with my friends. Loreto is a particularly interesting case, as its showpiece is the Holy House of Loreto, or as it is also known, the Flying House – the purported childhood abode of the Virgin Mary in Nazareth where, according to the Bible, an angel appeared to her to tell her she would give birth to Jesus, a feast day in the Catholic calendar dubbed The Annunciation – which according to the tradition was miraculously saved by angels so that it would not be destroyed by infidels after Christian crusaders were expelled from Palestine in the 13th century, and flown by them to its present location on the Adriatic coast.

I hold all revealed religions to be inherently daft, as any old bollocks will do in constructing one. At least Buddhism, which indulges in neither polytheism nor monotheism, and is more of a non-authoritarian guide for contented living, doesn’t go in for divine intervention of any kind to bolster its paths to enlightenment. At the same time, I try to cultivate in myself respect for people of faith, however ludicrous their gullibility may appear to me, and have no wish to offend them. People are welcome to their delusions, as long as they don’t start trying to foist them on me.

Of course, my pilgrimages would have to involve music. My first, and the first time I was ever outside Ireland, aged seventeen, was to see Bob Dylan play at Blackbushe Aerodrome in Surrey in July 1978. My mother stipulated that I couldn’t go unless my older cousin Raymond accompanied me. Thankfully, he did – which was kind of fortunate, as on the way back, sleepless at 6am, I nearly boarded a train for Glasgow instead of Holyhead, until he alerted me to the fact that this was not necessarily our preferred destination. I wrote a poem about the weekend round trip, a long meandering ballad which was accepted for publication by the late David Marcus in the New Irish Writing page of The Irish Press, my first appearance in a national outlet. And now here I am in the midst of this Moroccan musical trek, for the second time. As Bernard MacLaverty has it is his finely-wrought novel Grace Notes (1997), when describing the conclusion of his composer heroine Catherine’s creative journey: ‘Music: her faith.’ I might imagine myself more sophisticated than the regions of religious pilgrims, but I may well be just as much another kind of fundamentalist. After all, lots of people don’t get the fascination, devotion and reverence Bobcats have for Bob Dylan.

The afternoons are spent listening to some of the musicians play folkier jams, on liras (a recorder-like flute, quieter than the night-time’s oboe cousin, the rhaita), doumbek drums, lute-like ouds, and a bodhrán gifted to the village by an Irishman. A revolving door of players sit in for a while, have the craic, then go on their way, for all the world like a trad session in an Irish pub. The one constant, and the highlight for me, is Sheik Ahmed Talha, one of the most musically talented and humble guys you are ever likely to meet. A tebel drum player by night, he turns fiddle-player by day, improvising away with a bow on the strings of his instrument, held upright like a miniature double-bass, resting on his knee. Unlike the Bou Jeloudian suites of the evenings, these melodies come with vocals, and are really local folk songs.

Later on Sunday afternoon, when the sun has eased, a group of us walk to Bou Jeloud’s cave, a mile or two from the village. The legend begins with Attar, a young shepherd, who dared to rest in the forbidden cave of Magara, while his flock grazed on the greenery below. The cave was seen as taboo by villagers and, soon enough, Attar was roused from his slumber by the sound of pipes being played by the part-goat, part-man figure of Bou Jeloud – the ‘father of the skins’. Bou Jeloud made a deal with Attar: he would teach him the secrets of his music, on the understanding that Attar never share them. If he did break this vow, his teacher would be entitled to take a bride from the village. As is the way of these stories, Attar couldn’t keep the music to himself, and was heard playing by an infuriated Bou Jeloud, who then came to take his promised bride. The villagers kept to the bargain, but presented Bou Jeloud with the mad Aisha Kandisha, who tired him out with her insane dancing. Although briefly gratified, Bou Jeloud could eventually take no more, and left the village alone. Following his departure the villagers enjoyed a successful harvest. The ritual would continue each year, and time after time, Bou Jeloud would leave without a woman, and a rich harvest would follow. When Bou Jeloud finally vanished for good, Attar continued the ritual by dressing in goatskins himself, dancing with local boys who took on the role of ‘Crazy Aisha’. And so it continues to this day.

The final ascent to the cave is rocky and precipitous. Some of us make it up, some of us don’t. Last time, I didn’t, taking a perverse pleasure in making the journey and then not entering. This time, I manage to climb up, gingerly finding my footholds, and clamber inside. I’m obviously making progress in conquering my vertiginous fears. We gaze out at the sun declining over the rolling hills and valleys, verdant with their precious crop. J didn’t trust herself enough to get up here with me, or perhaps it was getting down afterwards that proved too worrisome. Ascent is only half the battle, and descent can be just as tricky. Maybe she will complete the final stage next time – if there ever is one.

Back at the ranch on Sunday evening we gather once again for an exquisitely lengthy post-prandial goodbye set from the Masters. Rhaita players sit in a row on one side, tebel players on the other, and work up their non-stop, improbably inventive rhythms, defying any conventional time signature. The percussionists pound out an incessant barrage of colliding patterns on their goblet drums (with sheep hides for skins), struck with a piece of wood shaped like a spoon in one hand and a thin stick in the other. Just as one passage of play is reaching a crescendo, one of the drummers will suddenly throw a curve ball change of beat, and the rhaita players kick in again, building another fugue, carrying on a follow-the-leader routine, constantly upping the ante, using circular breathing techniques to maintain the notes, until unified screeches ring out in ascension, gaining in intensity until the pitch is ringing out beyond the lavish tent, high into the homestead hills, reaching the starry sky above. And Jesus Christ, it is loud. Who needs electricity?

If you are going to attend the oldest, most exclusive dance party in the world, you better get up on your feet and get lost in gyrating to the pure sonic upheaval. It’s then you feel the music coursing through your body, and the visceral sensations transcend any rave you’ve ever been at, until you don’t know where you end and it begins. By moving alternately on the carpeted dance floor between the horns and the drums, you can control the mix. Ahmed El Attar, the group leader, lends a hand, setting aside his drum for the moment to entice all sitters to jive, starting with the prettiest women, but not stopping until even the most reticent man is on his feet. I watch as J cavorts with Marianne and Tomoko, her American and Japanese sisters. Then Bou Jeloud appears, brandishing his leafy olive branches, twitching with venom like a strung-out speed freak, and the bonfire is ignited. The diminutive Mohamed El Hatmi is a quiet, dignified village elder by day. Now, in the guise of the goatman, as if possessed, he attacks the musicians, the village boys, and ourselves with his sticks. We will doubtless be made more fertile, and a good harvest is guaranteed.

From a safe distance, Selma stands watching her grandfather perform with the other men of the village. Will the secrets of baraka ever be passed on from father to daughter, as well as from father to son? It will take a while to change a system which has existed since time out of mind. Or maybe it’s just not her thing. She has told us she wants to be a policewoman: a very perspicacious and practical career choice in these parts, considering the possible perks.

I have heard vague murmurs, accusing organisers and attendees here of ‘cultural appropriation’ and, even worse, ‘poverty tourism’ – in short, that the whole affair is just another hipster stop-off on some world music global circuit. All nonsense, of course. The concept of cultural appropriation is annoyingly imprecise and so deeply flawed. It seems to me to be little more than an academic version of the hoary old chestnut ‘Can white guys play the blues?’, which is insulting not only to the white guys (and girls) who love the music and want to play it, but also to the black guys (and girls) whom it exoticises as having a superior aptitude for expressing genuine feeling in a musically authentic manner because of their racial purity and troubled history. This is the equivalent of claiming, ‘My residue of inherited emotional hurt and suffering because of my ethnicity is greater than yours and, furthermore, is directly the fault of yours.’ It may be a valid area of enquiry for sociologists and postcolonial theorists, but it makes little or no sense to actual musicians. It’s as reprehensible as defining your identity around patriotism, which is, if we are still to accord with Dr. Samuel Johnson, ‘the last refuge of a scoundrel’. Even if such essentialism does account for part of what you are, why get so reductively precious about it? Why not, instead, share it? For the fact is that there wouldn’t be any blues at all if it wasn’t for cultural and racial miscegenation and cross-pollination. Blues music is a hybrid form derived from the meeting of African polyrhythms, field hollers and microtonal inflections with European melodic and harmonic structures and counterpoint, coming from the folk and even classical traditions – which is what makes it, along with jazz and rock’n’roll, North America’s greatest gift to the world. That slavery was a component in this process is undeniable and immensely regrettable, but such exclusionism is hardly going to retrospectively correct it now. For every Led Zeppelin, who had to be dragged through the courts before giving the African-American composers who influenced them the credit and royalties they or their estates were due, there was a Rolling Stones, who always gave songwriting credit to their musical progenitors, and through the 1960s British Invasion helped the U.S.A. to discover its own musical heritage, as well as making the twilight years of many original bluesmen and women a whole lot more comfortable. Just watch them worshipping at the feet of Howlin’ Wolf on Shindig! in 1965. Prior to accepting the booking, they had in fact insisted that The Wolf also appear on the programme, or else they wouldn’t.

As Zadie Smith has said in interview about her work, after the success of her debut novel White Teeth, “If I didn’t take a chance I’d only ever be able to write novels about mixed-race girls growing up in Willesden”, adding, regarding political correctness: “Identity is a huge pain in the ass.” Or, as Bernardine Evaristo put it more succinctly, “This whole idea of cultural appropriation is ridiculous. Because that would mean that I could never write white characters or white writers can never write black characters.”

Add to this that the music of the Masters is very much a live experience, of which all recordings are but an approximate representation. We hear sound and, by extension, listen to music, not only with our ears, but also with the rest of our bodies. Detonating shells set off supersonic blast waves that slow down and become sound waves. Such waves have been linked to traumatic brain injury, once known as shell shock. Symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder are often triggered by sonic signals: New York residents experienced this after 9/11, when a popped tire would make everyone jump; so too did Halloween bangers in Belfast and Derry during the Troubles. It is necessary to induce and re-enact the initial trauma, in order to heal it. As Keith Richards said in 1974, when many of his band’s contemporaries were concentrating on studio work, “A band that doesn’t play live is, to me, only half a band.” Plus, everyone who goes to the trouble of getting to Joujouka in the first place really knows their music, and is respectful of the people and the place. It’s about cultural appreciation, rather than appropriation.

Besides all of which, as Harry Sword reports in his book, Gysin was almost bitter when Hamri brought the Joujouka musicians to do shows in Tangier in the 1960s, as if the music should be kept secret. The same sort of protectiveness, which verges on proprietorship, can be found Paul Bowles writing, where it is evident that he was a somewhat colonial figure who saw old, underdeveloped Morocco as a tableau, and hated any modernisation. But this attitude underlines a disrespect and disregard for the people. Bowles wasn’t kind to Moroccans in that he was writing about a medievalesque Morocco, and disliked seeing that changing. But that somebody in Joujouka has a fridge is a good thing – otherwise meat goes bad and children get sick; or you can’t keep your insulin if you’re diabetic. Your lifespan is going to be reduced if you don’t have access to a road or a water system. Should that culture be preserved at the expense of modern healthcare?

There is also the hope that by bringing in visitors each year from all over the world, the children of the village will get a perspective of how important the music is, and in turn, keep it going.

And now, if you’ll excuse us, me and Sheik Ahmed are off to check our privilege.

Monday morning, coming down, we say our goodbyes, and share a taxi with a Japanese couple to Chefchaouen, the famous ‘blue city’, about two hours away to the east. We will have a relaxing week here, in a beautiful hotel with all mod cons, lush vegetation, hanging gardens full of bougainvillea and hydrangeas, loungers and a pool. We visit the medina, the Kasbah, have massages in a hamman spa, take a day trip to the waterfalls at Akchour. J’s recollections are of ‘The blue, the cats, the shower, the swing chair, the food, the swim in the pool so fresh, the echoing, haunting call to prayer – like bees swarming, at first threatening then meditative.’

On our last evening here, we climb to the disused Spanish Mosque, overlooking the town from a hill to the east, to watch the sunset, as many tourists, Moroccan and foreign, do. On the way back down, we hold hands and then kiss, almost as though we’ve just met a few days ago, for the very first time, and the years dissolve and reassemble around us.

It is notoriously difficult to capture the obliterating thrill of listening to music, much less playing it, never mind describing the music itself, in mere prose. It’s what makes most rock journalism, or any kind of writing about music, even and perhaps especially academic studies, painfully redundant. If anything can be said to, music partakes of the ineffable – and therefore is usually relegated to being discussed in terms of its theoretical structure or sociological impact. As a maxim attributed to several sources has it, ‘Writing about music is like dancing about architecture.’

So too, in my opinion, is writing about intimate relationships. Unlike some writers who have made great hay out of their marital problems and breakups (or, conversely, washed the clean linen of how enviably happy they are with their perfect partners in public), I have never wanted to capitalise on my disappointment, heartbreak and stress by writing about it in any directly confessional, memorial-ish way. I never wanted to be divorced (although, in fairness, perhaps some of them didn’t either). For proof – and while one should never tempt fate by speaking too soon, pretending a journey is over – I even waited long enough so that I could finish by recounting a reconciliation rather than a rupture. As far as I can see, most people don’t get divorced because of infidelity or domestic violence or the easily pleaded ‘irreconcilable differences’, but because they have grown bored with the patterns of the relationship they have established, and fancy a change. They want to try something different, or they start wondering if their lives would have turned out completely differently if they’d married someone else. Or else, they resort to unfaithfulness and partner-bashing and their differences being irreconcilable because they are bored, and need an outlet. Equally, most couples who choose to stay together – after a given time – do so ‘because of the children’, or because of their mortgages, or because they are fond of their creature comforts and dread a downgrading change. Or maybe some people even get good at getting divorced, after they’ve done it a couple of times. But there are different ways of being married, even to the same person.

For boredom, as we have established, is an inescapable fact of life. If it wasn’t, then explain games to me. Like chess, or its poor man’s version, draughts; or cards, be it anything from Bridge to Snap, or the gamblers’ Holy Grail, Poker; or golf, or Formula One motor racing, or even football. Or board games: they don’t call them bored games for nothing. They can’t all be accounted for by ambition expressed through competition, because very few people are good enough at them to compete at a level that really matters. Rather, all these activities are about passing the time. Granted, social theorists and educationalists will tell us that children playing games is part of the process of socialisation – learning how to deal with other people. But as J.M. Coetzee has the narrator of his novel Disgrace (1999) note about its protagonist David Lurie, an academic who has been downgraded to teaching Communications 101, ‘Communication Skills’, and Communications 201, ‘Advanced Communication Skills’:

Although he devotes hours of each day to his new discipline, he finds its first premise, as enunciated in the Communications 101 handbook, preposterous: ‘Human society has created language in order that we may communicate our thoughts, feelings and intentions to each other.’ His own opinion, which he does not air, is that the origins of speech lie in song, and the origins of song in the need to fill out with sound the overlarge and rather empty human soul.

Drone is about acknowledging this taedium vitae, and transforming it. Instead of being crushed by it, you are subsumed by it, putting it to good use. Drone slows time down, and makes room for memory. The journey is inward, as well as outward. You won’t hear the sound of yourself, or the sound of the world, or the sounds of the world inside yourself, or yourself in the world, unless you listen intently.

Unlike the exciting and/or relaxing holidays of flings and affairs, it is difficult to be married, to anyone. Although it can, on occasion, perhaps even often, be rewarding and fruitful. Good marriages, bad marriages: first they are good, then they are bad, maybe then they are good again, then maybe they are bad again. It’s a cycle. Irreconcilable differences? We have them every day of the week. Maybe all true love is a form of masochistic endurance. Try it, if you think you’re tough enough.

As for pilgrimages, they too can be one facet of self-mortification, as well as a way of merely filling in time. But, just as with my marriage, and just as with my lifespan on this earth – I came to dance. Did ye get healed? Oh yeah, we did. Just like every time. Joujouka has vouchsafed its miracle of harvest once again. But this time round, since it’s all circular and everything is connected, let’s have an epilogue instead of an epigraph. In my end is my beginning.

There is no intensity of love or feeling that does not involve the risk of crippling hurt. It is a duty to take this risk, to love and feel without defense or reserve.

William S. Burroughs, Letter to Jack Kerouac, from Lima, Peru, May 24th, 1954