In the mid-1990s Seosamh O Cuaig and I were filming a programme for TG4 in the State of Minnesota. It concerned an 1880 shipload of emigrants from Conamara.

In the city of St. Paul we were told that the term ‘Connemara’ was a century-old Minnesota synonym for lazy. This was curious, because nobody in the 19th century could survive on the rocky garrantaí of Conamara without hard, relentless physical work. There was no dole.

We learned that the ‘Connemara’ slander originated in 1880 when a Catholic Bishop, John Ireland, publicly blamed his financial troubles on a group of fisher-families from this area. He had taken them from their rocky fields and canvas currachs in the West of Ireland, and settled the oldest and youngest members of the families, against their will, miles from the city on the vast prairies.

They were instructed to become farmers. For the fit and young of the same families the bishop organized jobs in the city of St. Paul. Then came the worst winter in living history with temperatures thirty below.

The plight of those raw prairie dwellers was so desperate that they became the subject of national debate in the American Press. The Bishop, responding to WASP criticism, said they were too lazy to work. His criticisms were widely reported.

Naturally his urban flock and his separated brethren – the Freemasons of Morris County – did not doubt his word. But the Conamara immigrants, being neither literate or English speakers, could not defend themselves in that language, had no access to the print media.

In Spring the Bishop relented, the ‘Connemaras’ were delivered back to the city of St. Paul – which was where they had thought they were going in the first place. They made a success of their lives, one of them eventually becoming mayor of the city.

At least one Conamara family persevered on the prairie – that of Learaí Ó Flathartha – and also thrived. Nevertheless the slander of ‘laziness’ had persisted to this day, mainly because the immigrants could not defend themselves in English.

‘But,’ as Seosamh O Cuaig grimly said to me during the course of making the film, ‘I can read and I can write, in English’ Therefore we intensified our researches and the film eventually showed how these people had been used as scapegoats for the failed ambitions of the colonizing Bishop, a Republican and an entrepeneur. Helped by a laicised Bishop Shannon we detailed his predecessor’s personal ownership of the railway land awarded to him for the purposes of Catholic settlement. It seemed clear that as time was running out on his contract, Bishop Ireland used these poor people simply to buy time and fulfil his undertakings to his friends in the Railway company.

So fraught were his financial dealings that after he died his sister, a Mother Superior, destroyed all of the personal papers that related to the incident. But the mud stuck. Two Irish-American Minnesota lawyers happily told us, on film, that their Limerick-born father had emphasized to them: ‘Make sure people know you are from Limerick, not from Conamara.’

‘the cash crop’

Nearly a century after the Minnesota mess, in 1973 in Conamara I had recorded a vox populi with youngsters attending the Irish Summer Colleges in Conamara. All townies, they unanimously dismissed the place as consisting of nothing but rocks, with no attractions whatsoever. The locals, according to a few, were lazy.

How could they have made this judgment in three weeks? Presumably they had brought that bit of baggage with them from their suburban homes. Luckily, they know a little better now and there certainly is no local resentment to the Summer College industry.

Business is business and the modern students are referred to locally by the affectionate term ‘the cash crop’. Nevertheless, from Marx with his term ‘rural idiocy’ to Garret Fitzgerald’s opposition to Knock Airport; from John D. Sheridan’s bucolic ‘Thomasheen James’ to stand-up comics today, there is something universal in this urban contempt for rural-dwelling ‘culchies’.

The painter Michael FarrelI would jokingly ask sculptor Eddie Delaney and myself: ‘Are you two still rotting away in Connemara?’ The perception is based sometimes on ignorance, sometimes on fear of the wild men of the West.

A film editor whom I brought to Conamara years ago confessed to me that his ventures beyond the Pale had hitherto never brought him further than Leixlip – fifteen miles from Dublin.

Over the years, and quite separately, I remember two old friends of mine, a journalist and an actress, saying they felt threatened in the company of people in South Conamara. In forty years I have never felt thus threatened. My friends could not explain why they felt that way. I can only speculate on the reasons.

Dancing at the Crossroads

First, there may be resentment at the imposition of obligatory Irish on the monoglot English-speaking population of the island. This State policy was a Dublin invention but the resentment it engendered was directed at the imagined native speakers in their ghettoes in the West, as well as at soft targets like the writer Peig Sayers, and former Taoiseach (prime minister) and President Éamon de Valera, universally known as ‘Dev’.

The latter’s quite admirable ambitions for human beings on this island were regularly ridiculed. Incidentally, what precisely is wrong with good-looking girls and athletic young men, small local industry, and the human activity of dancing which Dev advocated?

Whatever his faults, Dev was way ahead of E. F Schumacher’s ‘Small is Beautiful’ philosophy. The small linguistic communities of the Gaeltachtaí may in the past have been a material source of resentment in that the grants the natives received were positively discriminatory and favoured Irish-speaking households. But they did not get electricity until 1956!

The pure and simple truth of the resentment, according to research by Mairtin O Catháin, published in the Galway Advertiser, is, as Wilde said, rarely pure and never simple. O Catháin showed that substantial Gaeltacht grants – not the petty ones based on linguistic facility but the serious ones for business and enterprise – actually benefit more the fictional ‘gaeltacht’ residents of booming suburbs such as Bearna, Moycullen, Knocknacarra and Claregalway than the actual Irish-speaking families in small villages like Cill Chiarån or Carna.

Garnering votes from such dense English-speaking suburbs once guaranteed Fianna Fáil success in elections to such quangos as the Board of Udarås na Gaeltachta. Indeed one of that party’s proud successes was a man from Claregalway who could speak no Irish whatsoever!

This is the pragmatic reason why the outrageously fictional extension of ‘the gaeltacht’, invented by Fine Gael’s Patrick Lindsay more than fifty years ago, could be maintained by Fianna Fáil’s clever directors of elections. The result is that the only community for which Irish is the first language gets a minimum of the kudos and all of the brickbats for speaking Irish.

The above Mr. Lindsay actually spent his retirement as my neighbour in Conamara. He once said publicly and in my presence that he was attracted to the place by its ‘touch of savagery.’ Despite his unconscious racism, the locals drank happily with him in Tí Michael Jack’s pub.

One can be sure that the modern version of W.B.Yeats’s freckled fisherman in Connemara cloth going to a place ‘where stone is dark under froth’ is no Irish speaker at all. He probably has a pad in Ballyconneely, Connemara where three-quarters of the houses belong to weekend visitors from Dublin and environs.

Then there is the neo-liberal urbanite’s association of the Irish language and rural life with poverty and idiocy. There is the canard that, as in the nineteenth century, incest flourished because the roads were bad and that this resulted in a population of malformed retards.

But a medical doctor’s RHA survey of Leitir Mealláin in 1891 – which I possess – described this community as the healthiest and handsomest he had ever seen. The endless parade of bright and beautiful young native speakers on TG4 for more than the past decade should by now have given the lie to that perception.

‘Going to the Source’

But a lie that’s big enough – as Goebbels proved – becomes the conventional wisdom. Years ago I attended a Temple Bar debate in Dublin where Dr. Terence Browne of Trinity College and Fintan O’Toole of the Irish Times locked horns. In the course of it Terence Browne referred to Irish as a dead language. Fintan did not disagree.

I had just driven up from my Béal an Daingin post office, where the staff and customers all joked and did their business in Irish. I mentioned this as evidence that the rumours of the demise of Irish might be exaggerated, and asked Terence how he could support his impression. His dismissive answer was couched in analogies to ‘dead’ Latin.

I concluded this was not personally researched, and a second hand opinion derived from the conventional East coast urban wisdom, i.e. that Irish was a suspect badge of the unholy trinity of nationalism, Catholicism and Provo-ism. I did not have the nerve to remind this fine scholar to take his own academic advice and ‘go to the source’, before dismissing the language.

The source of my own experience is over forty years living and working in the only bilingual community in Ireland, whose tradition is neither narrow nor insular: it knows Boston better than Enda Kenny, and all the main cities of England better than Bertie Ahern – in other words, Conamara is made up of men and women of the world.

Long before Sir Anthony O’ Reilly said Ireland was a great place to tog out in, but that the real game was ‘elsewhere’, the people of Conamara and rural Ireland in general were forced to explore that ‘elsewhere’. And it was not to play the gentleman’s game of rugby, but to survive their abandonment by the entrepreneurial class from whom O’Reilly sprang.

In the time I have lived in Conamara most of my work has been devoted to countering this subconscious racism, trying to persuade Irish urbanites – including its professional gaeilgeoirs – that my rural neighbours are not lazy thugs, but the hardest-working people I ever encountered; not ‘thick’, but the most coherent and smart, bilingual community in this island.

At a practical level, every family in Conamara could build their own house and make any repairs necessary, grow their own food, build a boat, excavate their own fuel, subtly negotiate the traps of central bureaucracy, and be on first name terms with their local and national public representatives. Such skills are pretty thin on the ground in suburbia and, when global warming intensifies, my neighbours are the kind of people from whom I will certainly be seeking survival advice.

Reference Group Theory

Years ago in Canada I learned the principle of reference group theory. It is better known as the pecking order, establishing who we are in relation to the echelons above and below us. Thus, Toronto English speakers look down on the French of Quebec. They both look down on the Scots of Nova Scotia who in turn look down on the Irish of Newfoundland or ‘Newfies’.

In the US the WASPS looked down on the Irish Catholics, who looked down on the Italian Catholics. And everybody agreed that all a Polack fish was competent to do was drown. At the bottom of the heap were the Blacks and then the aboriginal native Americans.

It was social benchmarking, each group maintaining its pecking order. Conamara is not entirely free of this. I have heard a man from An Spidéal expressing doubts about the degree of civilization of people twenty miles west of him.

Reference group theory is not just financially and socially alive in a class-ridden society such as ours. It has deep roots in our insecurities. It emerged in Kerryman jokes, yummy mummies and SUVs, the DART accent, Ross O’Carroll Kelly and especially the terms ‘culchies’ and ‘knackers’ It is accepted as part of the natural order.

But we are essentially social animals and have depended for our evolutionary survival not on our individual natures being red in tooth and claw, but on the social behaviour called cooperation which is designed to keep the more ugly parts of our nature under control.

No bypasses or rat-runs

It is a poor reflection of Western civilization that, before and since Hiroshima, the animal species most actively practising cooperation is the ant. The ruthless competitor, the profiteer at all cost, those CEOs who show a paper profit by getting rid of as many employees as possible are still our heroes, no matter how often they have revealed their feet of clay.

Is this an argument against Market values and modern Progress? Yes, if progress and the oil that lubricates the so-called free market and our modern lifestyle mean the death of community and consequent lack of empathy with our neighbour, quite apart from the distant deaths of hundreds of thousands of innocent Iraqis, together with the destroyed lives of 30,000 decent young Americans. Not to mention the imminent decay of our planet.

Is there any point anymore in pleading for non-consumptive lifestyles – not to mention understanding, tolerance, respect, love your neighbour, kiss a Traveller for Christ? Did the warnings of Mountjoy prison ex-Governor John Lonergan, or homeless children’s protector Fr. Peter McVerry have any effect?

Did Bono and Geldof and all the NGOs make us deaf to the fact that Charity begins at home? The corporations and advertisers who make so much money from our insecurities, fears and petty snobberies have set us on a material and metaphysical road which has no bypasses or rat-runs or backwaters.

There may be no escape from our unsustainable lifestyles and topsy-turvy values until the sea levels rise, oil runs out, the tankers grind to a stop and clean water is $100 a barrel. It will end in tears. Perhaps sooner than we think. But I am an optimist. That’s why I long ago embraced the rural life, planted trees for my six children and ten grandchildren and cut wood for my stove.

I believe that despite all the spin-doctoring, truth will out, that we are all now aware of our responsibilities, all travellers on the road to God-knows-where, tourists in the departure lounge, mice sailing on a ship of cheese. But I’m also realistic enough to remember Dorothy Parker’s words:

‘O life is a glorious cycle of song, a medley of extemporanea / And love is a thing that can never go wrong / And I’m Queen Marie of Romania.’

Do you think this piece is valuable? If so, you might consider providing us with financial support via Patreon, or simply pay us a small sum directly using PayPal: [email protected]. Thanks for supporting independent journalism. Subscribe for free to our monthly newsletter here.

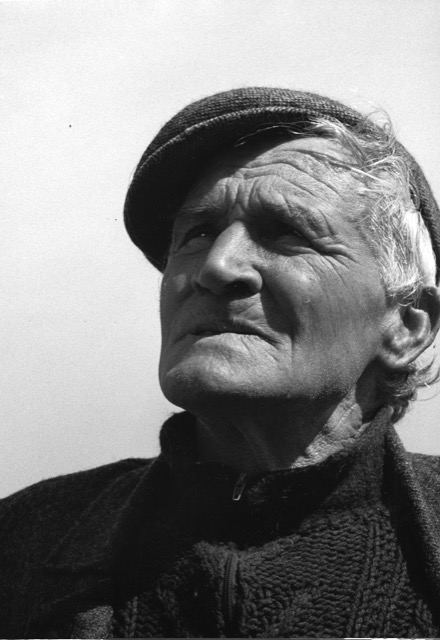

Featured Image is of Dara Beag O Fatharta.