I was pretty sure I was going to die, sooner rather than later, one midsummer’s night in Libya’s desert. It was 1988. A cousin of Colonel Ghaddafi, a military man, was driving us to meet the Great Man himself. In the darkness, we had turned left off the tarmacadamed main road between Benghazi and Tripoli, and were bumping over scrub and dunes on an invisible track, when the realisation dawned on me.

The convivial chat amongst my companions – an Irishman, an Englishman and my Arab interpreter – dried up, and silence filled the jeep. Suddenly it was quite clear: we were being brought out here to be shot.

I knew the Englishman had lied about his Public School background. Had Ghaddafi found this out and deduced he was a spy for the Brits? This was around the period Libya was supplying arms to the IRA.

I was mixing in strange company, but my excuse was scholarship: my work on the Irish/North African connection had brought me to the regime’s attention as a person sympathetic to Islam, and who might also be sympathetic to Libya and its Leader.

My interpreter told me that twelve months previously he had turned down an offer to become Minister for Information: ‘You don’t say No to this man, but how could I work for the regime, having seen friends hung in the public square?’

He too had good reason to be nervous. He was the one who introduced me to the concept: ‘Bone in My Meal’ – meaning there’s a fly in the ointment or, life is great except for one tiny thing.

We two Irishmen could not think of any reason why they should try to get rid of us, except as awkward witnesses. On the other hand, maybe we had corrupted his aides by persuading them to smuggle our hard liquor into this strictly dry country. Worse, I had allowed one of them to polish off half my vodka (he explained that vodka didn’t leave a smell on his breath). Were they suspicious because I wrote my daily notes in the Irish language, and their regular surveillance of my room frustratingly divulged nothing?

One morning, after crying off on an excursion, I answered a knock on the door to find three burly and embarrassed men. They carried one towel between them and pretended that was the purpose of their visit. They entered, installed the towel, and departed sheepishly.

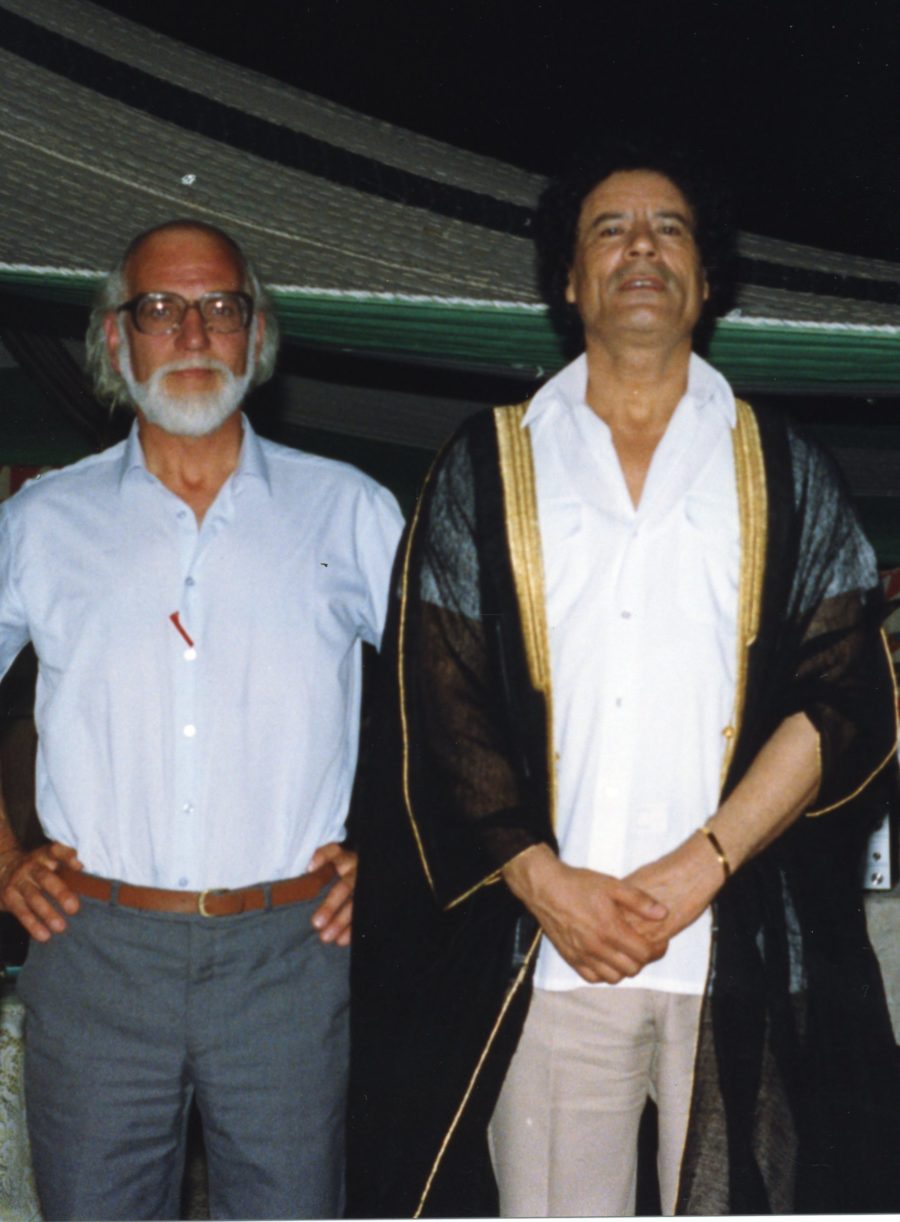

Perhaps I had not shown sufficient enthusiasm in the discussions about writing the Leader’s biography. Yes, it’s true. This was an exploratory visit. In preparation I had read most of the existing accounts of the man. The indigenous works were grossly sycophantic, the foreign ones mostly antagonistic, many written in British tabloid style.

Apart from a few objective demographic and economic descriptions of the country, I found only one account, Ghadaffi’s Libya, by Jonathan Bearman, with a preface by Claudia Wright, which struck me as fair-minded.

Perhaps I had insulted the Great Man at our first meeting when I spoke in Irish, leaving him and the interpreters upstaged until I translated my own words? I knew I was privileged. Five years earlier Kenneth Clarke, a Minister for Health representing the Thatcher Government, had hoped to meet Ghaddafi but was fobbed off with functionaries. My guides said the access granted to me was unparalleled in their experience. But I already knew flattery as the lingua franca of North Africa.

There again, it might have been my direct question: ‘How, sir, with the absolute power at your disposal, have you not become corrupt?’ Could the interpreter have translated that as an accusation?. No, not likely, because Ghaddafi replied: ‘But I do not have absolute power. The People have it.’

Hence the nervous silence as the jeep groaned and bucked all over the place. The military man seemed unsure of his path: he constantly peered around into the blackness, and occasionally up into the dark sky. I followed his glances into the dark and thought: ‘Yes, this would be a handy spot to lose four bodies.’ I had already seen the Kalashnikov resting handily on the floor beside him.

The driver suddenly jammed on the brakes. ‘This is it’, I thought. But all he did was get on the radio, and apparently ask for directions.

We resumed our helter skelter ride, and an hour later saw lights across the scrub. A circle of car headlamps greeted us. Should we be relieved, or was this to be some kind of show trial and execution?

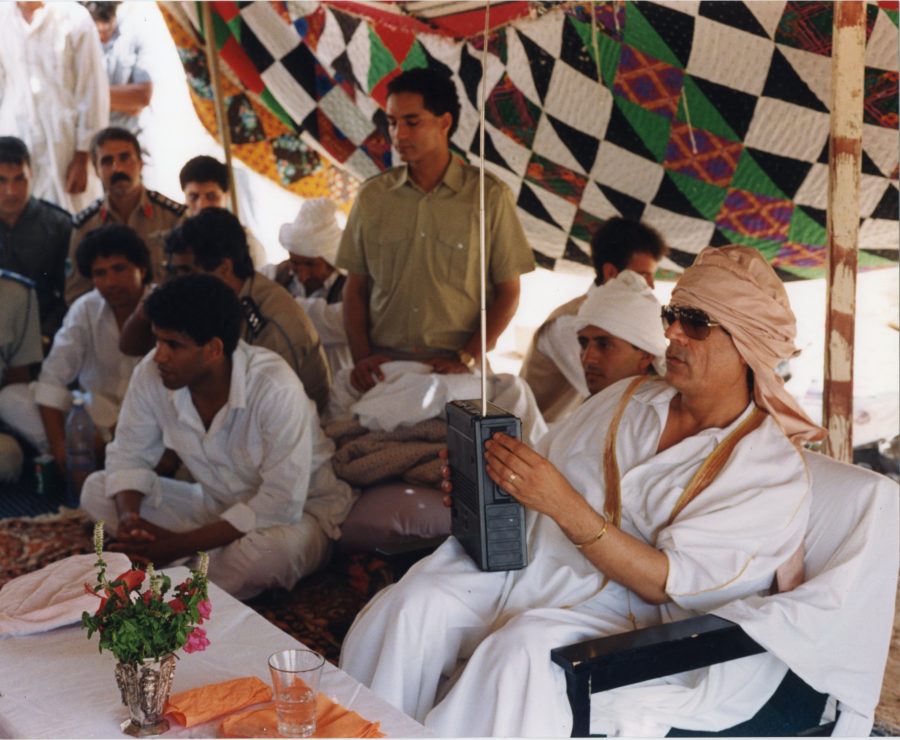

At the far side of the circle stood a figure straight out of Sigmund Romberg’s 1926 Broadway Musical ‘Desert Song’: a tall sheikh in flowing robes.

I have to confess that my first ever ‘encounter ‘ with North Africans was in a musical comedy in which I sang and acted in 1961, and in which I was described by the music critic of the Irish Times, the late Charles Acton, as ‘the only unconvincing character on stage’; a comment which fortuitously saved me from making a greater fool of myself in the theatre for the rest of my life. This did not, of course, prevent me from exposing my inadequacies in other areas.

A quarter of a century later Acton penned an enthusiastic endorsement of my Atlantean speculations, saying he was entirely convinced of an Irish-Bedouin musical connection. We never met.

The real Sheikh who now faced me was Ghaddafi. I realised this was his answer to my question about avoidance of corruption: the implication was that he was at heart a Bedouin, a man of the desert. The utter cleanliness of the desert kept man pure.

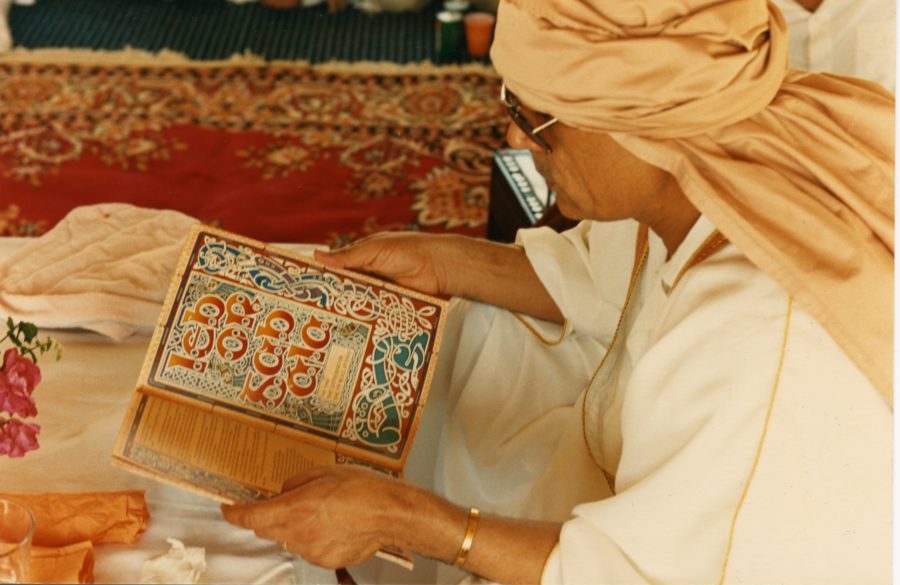

He answered my first question – about Bedouin incorruptibility – by handing me a jackrabbit and a pigeon which, to judge by their warmth and the tiny pulse I could still feel in the rabbit, were only recently sacrificed. These gifts did not reassure me.

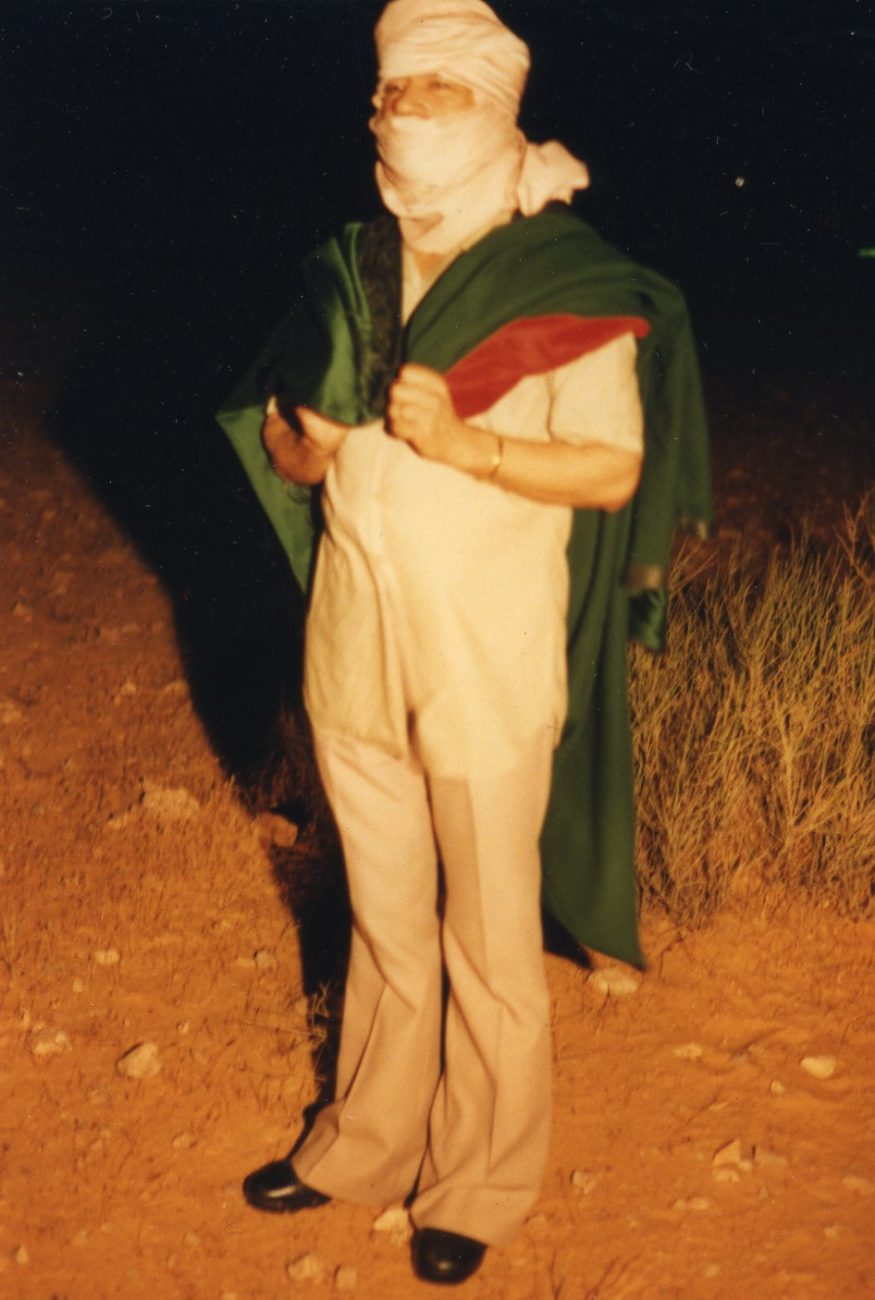

I thought I might as well get a photograph and sought his permission. He gestured to his Bedouin costume and half-grinned: ‘If they see me dressed like this they will certainly say I am a terrorist.’

A rug was spread on which we sat, in front of a small fire. Our host lowered himself onto a stool, deftly slipped into place by an armed female bodyguard, one of his so-called ‘revolutionary nuns.’ He did not even glance behind him. ‘Now that’, I thought, ‘is the confidence of power’. She also draped a cloak around his shoulders and made sure we kept a respectful distance. Then, of all things, he poured us each a cup of tea.

In an effort to avoid staring, I ventured that in his youth in the desert he must have often drunk tea round a fire like this. ‘No’, he said. ‘We did not have the luxury of tea in those days.’

That put me in my privileged Western place. Conversation with this man had not been easy. Perhaps he just wanted to be stared at.

Then I had an inspiration: I remembered that the feast of Abraham’s sacrifice of his son Isaac was imminent. It had seemed to me that Ghaddafi’s father was sparsely mentioned in accounts of his life – even though the father lived to the age of ninety-five – whereas the Leader’s mother was very prominent in despatches. ‘Ah-ha’, thought I, ‘maybe there’s something Oedipal in the background’.

‘I wonder’, I said, ‘about Abraham and Isaac and your relationship with your own father’.

‘I share your wondering’, he said and refilled my cup.

No more questions for the moment, your honour.

The Englishman referred to an alleged whipping episode of Arab boys by the Brits in Egypt. He asked whether this had fuelled the Leader’s anger.

‘Not especially’, he replied, ‘I saw all of humanity being whipped, I saw cruelty towards humanity everywhere.’

I realised this man should have been a film director. He did in fact finance the epic ‘Lion of the Desert’, at a time when oil revenue was unparalleled. His four months of army training in England were largely spent at Beaconsfield – now the location of the National Film School. The elaborate scenario he had set up for us was a masterpiece of wide-screen cinema. Only the dialogue needed a little polishing. We were flattered at the show put on for us but, needless to say, were, quite literally, a captive audience out there in the desert.

There was a certain amount of polite conversation which did not last long. My fellow Irishman made a reference to Samuel Becket, quoting the phrase ‘Imagination dead Imagine’, which resulted in blank looks all round. I’m still not quite sure what his point was.

I enquired, fairly disingenuously, whether Mr. Ghaddafi saw himself as a kind of philosopher king in the Socratic mould. I forget the answer, if he gave one at all. The conversation was desultory. What must he have thought of these idiot Irishmen who spoke of literature and philosophy as if they were keys to understanding life’s great mysteries?

In a practical tone, Ghaddafi referred to a letter he had written to Kurt Waldheim about Bobby Sands and the Hunger Strikers. I mentioned the book Ten Men Dead by David Beresford and Peter Maas, and he asked me to send him a copy. I never sent it.

After perhaps a half-hour he stood up. The conversation petered out. Our minds, I suspect, were running on parallel tracks miles apart, and consequently doomed never to meet. He seemed to be satisfied he had made his general point: that the ascetic life of a desert Bedouin was the ideal on which to base one’s life and society. Mind you, the fancy suit, possibly Armani, that peeped out from under his desert robes slightly undermined the homily.

A large dormobile drove up. The Leader rose, shook hands, vanished into its interior and off it trundled into the blackness. Our guide explained that the Leader suffered from some arthritic condition; hence the dormobile. I was assured that I would have at least sixteen – a figure plucked out of the air – meetings with the man, and that if the biography was successful I would be commissioned to make a film of his life with an unlimited budget. With these dreams of grandeur we were left to face the uncomfortable ride home across the scrubland. At least we were still alive.

It wasn’t the end.

On the way back a couple of jackrabbits were trapped in the corridor of our headlights. Our driver stopped the jeep suddenly, grabbed his rifle and leaped from the vehicle. Laughing, he began blasting away at the terrified animals. It was as if he was relieving the tension of the past few hours. He missed. I got out to stretch my legs and he offered me the rifle. I declined, much to his surprise.

We slept uncertainly that night wondering what other scenarios Mr. Ghaddafi had in store for us.

********

Some months later in the Crane Bar in Galway I met five American students bound for London to catch a PanAm flight back to New York, and their University in Syracuse. I admit this may be hindsight, but even in the presence of my lively two-year-old, they seemed unusually subdued for young people. I don’t believe in premonitions. Maybe they were just worn out with travel.

A couple of days later I heard about the horror of the plane crash in Lockerbie, Scotland. The news bulletin said many of the passenger were students from Syracuse University in New York. When it emerged that a bomb was the cause, the finger was pointed at Libya.

I did not refer publicly to my encounters with Ghaddafi until much later. I feared my musings might endanger the people who confided in me there – despite their urgings at the time to tell the world. I hope it is safe for them now if I mention in passing that one of them brought me to a beach in Cyrenaica and said: ‘When you go home, tell the Americans that this is the easiest place to invade.’ Not far away was a place called Tobruk, which even I had heard of.

Interesting things happen to me in North Africa.

All images (c) Bob Quinn.