Today bottled spring water is an everyday drink, and sales run into the billions every year throughout the world. In polluted cities many inhabitants don’t trust the public water supply and use it only for washing. For relaxation and thirst quenching they are willing to pay for bottled spring water from their own country or imported from distant lands.

Indeed, there is a widespread belief in the value of spring water, even if in many localities tap water is just as rich in mineral content as the bottled water described with impressive statistics, on colourful labels.

Throughout continental Europe, as far back as Roman times, people have made secular pilgrimages to springs and wells with folkloric reputations. During the so-called Celtic era around Britain and Ireland people flocked to holy wells which they believed contained magical healing powers. Christian evangelists like St. Declan and St. Patrick acknowledged the ancient beliefs and urged their flock to say prayers and perform penitential rituals at these water sources – hence the designation of thousands of Holy Wells throughout England, Scotland, Wales and Ireland, many of which have vanished into oblivion as a result of changes to the underground water table and urbanisation.

19th century photochrom of the Great Bath at the Roman Baths.

Bath

The springs at the base of hills near Bath in Somerset, a town founded by the Romans about 60 AD, were cherished from Celtic times for their purity and health effects, but the Roman emphasis on hygiene gave an added boost to the reputation of the place and over the centuries Bath developed into a major health resort.

Hydrotherapy i.e. the medicinal use of water, became fashionable from the late 16th century. People bathed in cold waters, rubbed painful parts of their bodies with water, or bathed in thermal springs to relieve arthritis, rheumatic pain and other ailments related to skin, stomach and bodily organs.

In continental Europe from the end of the 18th century onwards members of the landed aristocracy began holidaying in rural idyls, often in the mountains, where chalybeate waters were found.

In this period, Hotels were founded to cater to the card-playing, horse riding and other costly inclinations of this leisure class of visitors. The urban haute bourgeoise followed the fashionable aristocratic trends.

In the heyday of the Austro-Hungarian empire Kurorte (places with reputations for curative waters) thrived. It could be a mixture of complacent decadence and health seeking. Many places in today’s Czech Republic, Hungary, Austria and south-eastern Germany still incorporate the word Bad (baths) in their names. The languid decadence has departed and serious health therapy regimes now prevail. Trades unions in Germany and elsewhere organize health holidays for workers and their families.

A geyser in Karlovy Vary, Czech Republic.

Irish Health Waters

In the 18th and 19th centuries several places around Ireland were major attractions for both rich and poor seeking comfort and cure from health-giving waters. Local economies thrived as hotels, shops, taverns and local transport catered seasonally to thousands of visitors coming from England and closer to home.

Only Lisdoonvarna in Clare remains to remind us of a tourist boom from former days. Below are a few details about places that once featured on the health map for urban sophisticates.

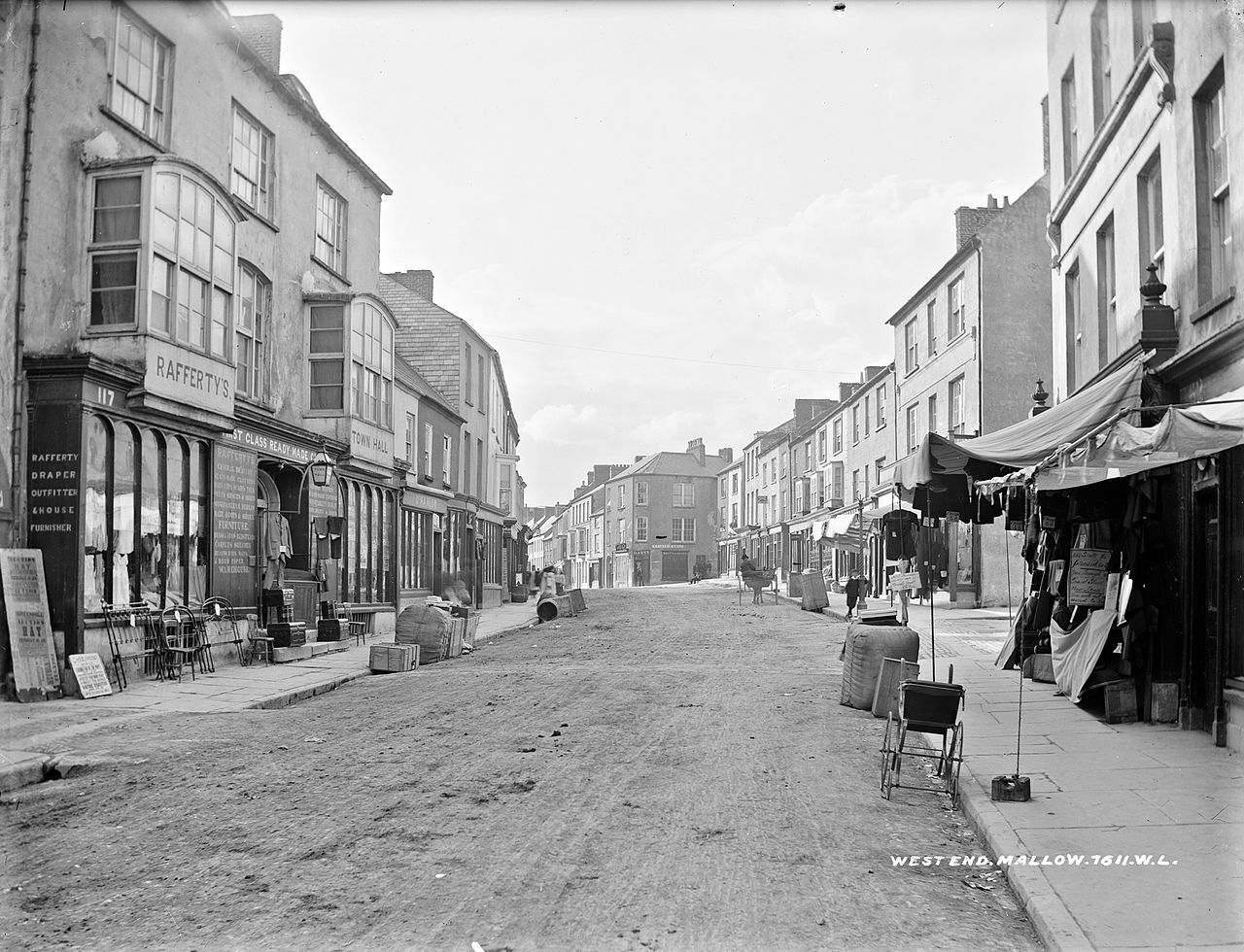

Thomas Davis Street (Main Street), Mallow in August 1903.

Mallow Springs in Cork

With the advent of Christianity one of the Mallow springs was dedicated to St. Patrick. The largest of the group is known as Lady’s Well. The belief that the spring had medicinal properties stems from the work of Dr. Rogers of Cork, who in 1727 treated a sick woman in Mallow and observed that the only liquid she could retain was water from the spring.

After her recovery Dr. Rogers invited Mr. J. Rutty from Bristol Spa to visit Mallow. Rutty wrote a book called Mineral Waters of Ireland, published in 1757, and highlighted the medicinal aspects. He quoted Dr. Rogers as reporting a wide range of cures including for: disorders of the stomach and skin; respiratory problems such as catarrh, coughs, and asthma; urinary disorders; and diabetes. Mallow became a popular health resort for about thirty years, especially in spring and autumn, but by 1850 it had ceased to function due to the social effects of famine and a switch of focus on English spa towns and glamorous resorts on the continent.

Mallow seems to be the only place in Ireland where thermal springs were known to exist. Many modern 5-star hotels offer so-called spas, which are really designer ‘hot tubs’ and Jacuzzis in luxury wellness centres created for moneyed holiday makers.

Struell Wells, near Downpatrick, County Down (pictured in feature image).

Located about three kilometers from the historic town of Downpatrick in Down, Struell (derived from the Gaelic word tSruthail or stream) comprises two wells, two bathhouses and the ruins of a church. It is a remarkable archaeological site. The evidence from Struell strongly suggests that it was an important sacred site in pre-Christian times. It is not far from Saul where St. Patrick is said to have met Dichu in the fifth century and made his first convert.

There are two roofed wells believed to have curative effects, the Drinking well and the Eye well. From the 17th century until the 1840s Struell was a popular place of pilgrimage. Today it still attracts people in search of cures and spiritual inspiration, and is an important stop on the St. Patrick Trail laid out by the Ulster tourism board.

Swanlinbar, County Cavan

In the 18th century people from England flocked to the three spa wells near the village of Swanlinbar, near the border with Fermanagh. Three wells had water rich in mineral trace elements and had a “rotten egg” taste and smell.

A hotel located at the well in Gortoral hosted the health pilgrims, who were told that drinking the water would allay scurvy, depression and bad appetite. The rotten egg flavour comes from the sulphur content.

Drumod well just south of Swanlinbar is still accessible and attracts visitors to this day. In his book about the mineral waters of Ireland above mentioned J. Rutty devoted many pages to the area of Swanlinbar and spread its fame around Britain and continental Europe.

The remarkable tale of the healing waters of Ballyspellan in Kilkenny https://t.co/DDI4Cbfqsx

— Kilkenny People (@KKPeopleNews) November 26, 2021

Ballyspellan Spa in County Kilkenny

Ballyspellan Spa, about 20 kilometers from Kilkenny city, no longer exists, but the spring water that flows through the limestone-rich Clonmantagh hills is still available to visitors who know about the medicinal properties.

There is a well near Johnstown village where people go to fill bottles with the water. In the early 18th century the gentry of Dublin and other towns made holiday visits. Rochfords’ Hotel nearby offered hospitality. Some of these well-heeled visitors enjoyed hunting foxes and hares, horse racing and dancing. Hurling was another attraction for whoever enjoyed the clash of the ash.

The poet Thomas Sheridan wrote about the spa. The area was the birthplace of Dr. Ronan Tynan, a noted singer, bone setter and limb amputee. Long after the fashionable gentry ceased to spend their holidays in the area the well remained a summer focal point where locals congregated to drink the water and divert themselves with sports and pleasant conversation.

St. Munn’s Well at Brownscastle in County Wexford

Near Taghmon in County Wexford ‘patterns’ were held during the 18th century on the saint’s feast day 21st October. The waters at nearby St. Munn’s Bed were sought by pilgrims in search of cures for back ailments.

Unfortunately, however, a lot of drunkness and fighting ensued from the partaking of strong poteen distilled in the hills and sold to pilgrims, and by the early 19th century the annual custom was banned by the clergy, but some locals continued visiting the place discreetly.

In the mid-twentieth century two local men, Jack Sinnott and Christy Murphy drained and piped the vicinity and Seamus Seery with others built a footpath access so that the general public could visit without difficulty.

Lisdoonvarna in County Clare

The medicinal waters of Lisdoonvarna were first written about around 1740 and the gentry from far and wide began flocking to an area not far from Ennistymon in County Clare, where no village existed at the time.

In the second half of the 19th century hotels were built and the precious waters, rich in sulphur and iron, were under the control of private owners. The Guthrie family built a pump house for dispensing the water, one prominent woman in the family being known as Biddy the Sulphur. A certain Dr. Westropp purchased the site and introduced baths. The main visiting season was in September when harvesting was complete. Several hotels and boarding houses competed for customers.

Lisdoonvarna became associated with matchmaking as parents brought marriageable daughters on holidays there. Matchmaking festivals still take place, and many young people independently take trips to Lisdoonvarna in search of fun and friendship.

Although I have never tasted the sulphur waters, Lisdoonvarna is important has a personal significance as it is the place where my parents met in the autumn of 1942: my mother visiting from Limerick and my father from more distant Kildare.

Lisdoonvarna has attracted German and other young continentals seeking out pubs in Clare where traditional Irish music is to be heard. The popular song Lisdoonvarna was first sung by Christy Moore in the 1980s, and helped publicise the folk music festival. It is fair to say that drinking pints in ‘singing pubs’ is now more popular than ‘taking the waters’ among this age profile.

Glencar Waterfall at Glencar Lough.

Lesser Known Spa Waters in County Leitrim

Several localities which are not well known nationally have water springs and wells that have been sought out by health connoisseurs.

County Leitrim has sulphur and chalybeate (iron-rich) water sources. Around Sliabh and Iarainn (the iron mountain) overlooking Lough Allen in mid-Leitrim old ordinance maps indicate the presence of twenty spa wells, but hardly anybody visits the spots nowadays, although hillwalkers find the whole area overlooking Lough Allen attractive, and remains of old sweat houses can be found. In the Mohill district the neglected remains of a spa well rest obscurely on a private farm

Drumsna in South Leitrim is reputed to have a number of sulphur streams, not universally prized by locals on account of the ‘rotten egg’ flavour and smell.

One well in MacManus Cross, between Jamestown and Carrick-on-Shannon is still visited by individuals seeking water to cure worms in children and horses.

Not far from Dromahair in North Leitrim is a little-known locality on the side of a wooded hill known as Derrybrisk (Doirebriosc in Gaelic, which suggests woodland with oak trees).

Older inhabitants of Dromahair, Killenummery and Ballintogher remember sweet summer Sunday afternoons until the 1960s when people from the adjoining townlands and visitors from Sligo town, arriving on bicycles, congregated at Derrybrisk spa, as it was then known. Card playing and chatting was the point, not tasting the sulphur water. Farmers came to fill bottles of the sulphur-rich water and use as medicine for sick animals. The water, diluted in ordinary water, was also said to cure worms in young children.

The advent of motorised transport and mass media such as radio and television seems to have brought these social afternoons to a halt. The spot is difficult to access today. Several farms in the Ballintogher area have streams tasting of sulphur, indicating that there is a lengthy vein of sulphrous limestone in the hills around.

Modern medicine and improved diets have lessened the traditional appeal of medicinal waters, but folklorists and natural health enthusiasts hanker after the old ways.

Leitrim largely missed out on the 19th century enthusiasm for taking the waters, but today the ‘forgotten county’ as it is sometimes termed, is ripe for a reimagined rural outdoor tourist industry.

Hill walkers can be brought on guided trips to view the remains of archaeological sites and curiosities. Old abandoned sweat houses, spa wells, holy wells, dilapidated monastic sites, dolmens and abandoned mining projects – all these and some important War of Independence memorials invite domestic and foreign tourists.

Craft whiskey and gin are among other spirit waters which have made an appearance. In Drumshanbo in mid-Leitrim Gunpowder Gin has proved to be a dynamite product for domestic and export consumption. Now if only a daring chemistry graduate would invent a novel sulphur water-based alcohol elixir, preferably with the rotten egg smell removed.