To tell you the truth, I could easily have been a father, and I would be a father now, had my wife J not miscarried a baby we once made. This was in 2002, so he or she would have been eighteen by now. So strange to envisage it: another life – for me, for J, and for that life. And had that bundle of multiplying cells survived to become an independent living being, would it have fundamentally altered the attitudes I am expressing now? Or confirmed them? Although I have to confess that for the most part I was just going along with the whole plan for J’s sake.

Women feel motherhood from the time of conception. Men don’t feel fatherhood until they are holding their child. I even remember a trip to Holles Street Maternity Hospital to make a sperm donation, so that it could be tested for any abnormalities, due to side effects from other medical treatment I had been receiving. The next time I went to that place was to visit J in a ward when she was recovering from losing the baby. She hadn’t even known that she was pregnant.

In the first of a series on his attitude to having children Des Traynor explores his upbringing and argues that being anti-natalist is not to be unnatural.https://t.co/GnTht5jurt@broadsheet_ie @BowesChay @corourke91 @danieleidiniph1 @IlsaCarter1 @KevinHIpoet1967 @GarzonVico

— CassandraVoices (@VoicesCassandra) November 1, 2021

I said terrible things to her, while she’d been campaigning for me to father her child, before I acquiesced. I’d told her she was only making love in order to conceive. I’d told her she would be a terrible mother.

Despite having her own human foibles, I was wrong – if for no other reason than the fact that she is nothing like my mother. Just as I am nothing like her father – a fear she speculatively expressed early in our relationship. Of course, she could have been a bad mother for entirely different reasons than my mother was, but, just as equally, possibly not. And how will we ever know, now?

All she ever wanted was for us to be a family. All she wanted was to nurture, to have some extension of herself to love. I was not mature enough at the time to grasp that. Instead, I’d asked her, fearing for our freedom, “What will you do with this baby?” To which she’d replied, not seeing any problem, “Love it.” (‘What you get married for if you don’t want children?’ T. S. Eliot, The Wasteland, II. A Game of Chess. Companionship, Tom?) I can only excuse such wretched behaviour by pointing to Paul Stewart’s study of Beckett, Sex and Aesthetics in Samuel Beckett’s Work (2011), where he deflects accusations of misogyny in the maestro’s oeuvre by positing that because for him women represent the threat of progeny, they are therefore simultaneously desired and reviled.

Having mined his upbringing for clues in part 1, Des Traynor draws on the literary canon and the Irish Constitution for insights into his attitude to having children.https://t.co/qyewMrsMpJ@broadsheet_ie @Des_The_Dog @BowesChay @BenPantrey @danieleidiniph1 @KevinHIpoet1967

— CassandraVoices (@VoicesCassandra) November 8, 2021

Reincarnation?

Speaking of women, not to be upstaged, my mother chose to end her time on Planet Earth while J was miscarrying (which began before but ended after Mam died). Had J gone on to discover that she was pregnant, and had we given birth to a healthy baby, I would have read that as my mother giving us a parting gift, almost a reincarnation of her spirit.

As it turned out, I see it as my mother robbing us of our unborn child, taking our unformed baby away with her, instead of leaving it to us – as though we were unworthy, as though she didn’t trust us with it: the last thing she took from me. My mother was always terrified that I’d get someone pregnant out of wedlock. Hey Ma, not to worry: I didn’t. But when I did get married and make my wife pregnant, nothing came of it. Is that some kind of subtle revenge? And if so, by who on whom?

I could still be a father now. But not if I can help it. J can no longer be a mother. If this is still a source of sadness and regret for her, I apologise profoundly and profusely.

Foreign Adventures

Freedom?

‘Fearing for our freedom.’ Did we do so much more with it, than the breeders in our circle of friends and acquaintances? Sure, we were able to holiday in Italy, Portugal, Spain, Greece, Morocco and India, while they had to settle for annual summer trips to the Aran Islands; and we were able to take weekend city breaks to Paris, Amsterdam, Delft, Bruges, Ghent, Prague and Tallinn, while they were not kicking back but rather gearing up to arrange play dates and other activities to keep the children occupied during the days off, and ferrying them to and fro – because we didn’t have to worry about getting kids on and off aeroplanes, and because we had more disposable income.

Not that we had that much more: we just didn’t have to make as much, and what we had went further. I certainly got to go to way more gigs than my peers, not having to worry about sourcing competent and reliable babysitters and being able to afford to pay them. I’ve probably read a lot more books than someone preoccupied with childcare.

If you think the trade-off wasn’t worth it, then prove me wrong.

Paternal Bonding

Son or Daughter?

If I had had children, would I have preferred a son or a daughter? The latter, hands down. Fathers favour daughters, mothers favour sons (and, generally, vice versa) – or rather, a parents’ relationship with a same sex child is usually more complex and fraught than it is with a child of the opposite sex.

Shakespeare was fond of daughters as redeeming of all fathers’ misdeeds, at least in the later ‘romances’ (Pericles’ Marina, The Winter’s Tale’s Perdita, Cymbeline’s Imogen, The Tempest’s Miranda). However, his earlier King Lear, that most mistreated of parents – even if he did bring much of it on himself – also had daughters, and it didn’t really work out so well with the first two.

Admittedly, he did have one loving, dutiful daughter, notably getting it right with the youngest, to compensate for the elder two cruel, self-interested termagants he also spawned. One out of three ain’t bad. But Cordelia dies anyway. That’s the difference between romance and tragedy. But while there may be some slim hope for a daughter, becoming a father of a son instantly marks you out as a bad guy, to be rebelled against and toppled – even, if we are to take the story of Oedipus literally rather than metaphorically, to be killed.

While much depends on the extent of your offspring’s sedition, it is kind of impossible to win, as a Dad. No way am I re-enacting that particular little domestic yet universal drama. Some may say I am merely operating out of fear of failure as a father, and am crippled by such anxiety, which is itself a kind of self-fulfilling prophecy: because I think I will fail as a father, I will fail as a father. But all fathers, and mothers, fail, to a greater or lesser extent.

To recast a favourite formulation from Beckett: to be a parent is to fail, as no other dare fail. Then again, ‘Try again, fail again, fail better.’ But how many0 chances do you get in one life to succeed? Maybe better not to try at all. Others may posit that my lack of progeny, because of distaste at the world, because of its inherent unfairness, is also a self-fulfilling prophecy: that is, because I view the world as distasteful because it is unfair, having progeny would have turned out to be distasteful and unfair too, for me and also for them – rather than redemptive. And, indeed, it is true that one has to somehow believe in life, and the future, to have children. Or, at least, it helps. But for those who identify with Miguel de Unamuno’s Tragic Sense Of Life, the whole enterprise can seem somewhat futile. In any case, I view the failure of parenthood as inevitable – because even the most conscientious of parents will tell you that you can look after your children only up to a certain point, and you can’t stop them from making all those stupid mistakes that you made (even those you know about).

Actually, I think I would be – or rather – would have been, a pretty good father, all told. But what if, for a myriad of unforeseen reasons and circumstances, I wasn’t? I see no reason to make an irreversible bet on finding out. I don’t think the odds are great, and I still don’t see the percentage in it.

The Act of Parturition

I have always found the thought of the act of parturition, that is giving birth by pushing a baby out into the world, vaguely repulsive, definitely messy and probably very painful.

How do women do it? Maybe I’m just a wimp. Or maybe not, since quite apart from all the blood and guts involved, you can even die while doing it. (Is it really any wonder that 10 to 15 per cent of women suffer some form of postnatal depression, and that one in a thousand develop puerperal psychosis, given the utter physical trauma attendant on forcing yet another member of the next generation out into this hostile world?)

It has always reminded me of the chestburster scene in Ridley Scott’s Alien (1979), a sequence specifically designed to prey on male fears, according to critic David McIntee in his Beautiful Monsters: The Unofficial and Unauthorized Guide to the Alien and Predator Films (2005). ‘On one level, it’s about an intriguing alien threat. On one level it’s about parasitism and disease. And on the level that was most important to the writers and director, it’s about sex, and reproduction by non-consensual means. And it’s about this happening to a man.’ He notes how the film plays on men’s fear and misunderstanding of pregnancy and childbirth, while also giving women a glimpse into these fears.

Similarly, David Lynch’s Eraserhead (1977) taps into themes of tokophobia and fear of fatherhood, while Roman Polanski’s Rosemary’s Baby (1968) envisions pregnancy and childbirth as a form of Satanic possession.

But birth is where we all come from (unless we’ve been cloned, or are the products of in vitro fertilisation, without the subsequent implantation in a uterus – a far safer and more sensible way of doing things, in my opinion), so there must be nothing to it. (Ducks and runs for cover.) I’m joking, of course.

Any account of giving birth I’ve heard or read makes it sound like it takes place in a low circle of hell. (‘They don’t call it labour for nothing’, etc. ‘Push! Push!’ Adam’s – and, more’s to the point, Eve’s – Curse.) Anne Enright, Claire Kilroy, Sinead Gleeson and Jessica Traynor have all written eloquently on the vicissitudes of accouchement (some more affirmatively than others), but the prize for most visceral description must go to Shulamith Firestone, who in The Dialectic of Sex: The Case for Feminist Revolution (1971) wrote that ‘…childbirth is at best necessary and tolerable. It is not fun. (Like shitting a pumpkin, a friend of mine told me when I inquired about the Great-Experience-You-Are-Missing.)’

Always allowing for the possibility that those describing the process are exaggerating for effect in order to elicit kudos, there still has to be a better way of doing the thing – if doing the thing must be done. Indeed, it is the same Firestone who was an early proponent of cyberfeminism, that is the idea that women need technology in order to free themselves from the obligation of reproducing, thus pointing to a future in which individuals are more androgynous and views of the female body are reconstructed. Her arguments have been subsequently developed by Donna Haraway, who in A Cyborg Manifesto (1985) sought to challenge the necessity for categorisation of gender, positing that gender constructs should be eliminated as categories for identity.

About the many and various sexual acts I have performed, I can attest to no corresponding squeamishness, or horror of bodily functions, on my part.

Stroller or Buggy?

I also have a morbid fear of the vehicles known variously as Buggies (European English), or Strollers (American English). Can we settle on the more universal and neutral Pushchairs, or the perhaps posher Perambulators? – although which term we employ can create some ambiguity as regards signifier and signified: are we referring to the smaller, fold-up apparatuses where the baby sits facing away from the pusher; or the larger, more solidly built contraptions resembling nothing so much as a Sherman tank going into battle, where the little stranger faces their means of locomotion?

Whatever you care to call them – and in any case it is both I have in mind – I defiantly distance myself from them in the street and in supermarkets, full sure that they have no other purpose or mission than to nip at my heels, or crash into my shins, or crush my toes. Those in charge of them should really be more careful. Perhaps these ‘go-cars’ and ‘prams’ should come with a health warning; or better still, be licensed.

Cyril Connolly famously singled out ‘the pram in the hall’ as one of his Enemies Of Promise (1938), a phrase, along with ‘the tares of domesticity’, that has been seized on by a subsequent generation of feminist criticism as blatantly misogynistic (although maybe not so anti-women as previously thought: vide the reference to Sheila Heti’s Motherhood above). ‘The overarching theme of the book…’, according to that ever-reliable critic Wikipedia, ‘is the search for understanding why Connolly, though he was widely recognised as a leading man of letters and a highly distinguished critic, failed to produce a major work of literature.’ And we think we invented ‘creative non-fiction’? The full quotation from Connelly reads: ‘There is no more sombre enemy of good art than the pram in the hall.’ Me? I don’t even have that excuse.

Bouncy Castle

While we’re on subject of loathsome objects best avoided, here are two words guaranteed to strike fear into the heart of any prospective parent: bouncy castle. Also, on the positive side, it’s an unalloyed boon that I will never be obliged to read the Harry Potter books, and pretend to like them. For these small blessings, much thanks.

Most young parents of my acquaintance seem to spend their lives merely running a busy creche with someone they used to go out with (or ‘date’, as the Yanks say). More generally, openly declaring oneself an anti-natalist from the outset (out of the closet!) does help to circumvent that tiresome “Where is this relationship going?” discussion, raised at a certain point in most fledgling liaisons – at least by people whose main objective in their amatory affairs is to conduct a round of interviews for potential husbands and fathers (or wives and mothers); while furthermore, in the longer term, contributing to the avoidance of the workmanlike rigours of ‘trying for a baby’ (those daily doses of folic acid!), which can only turn what should be a spontaneous pleasure into a meticulously planned duty roster.

Imagine even having to attend a Parent/Teacher Meeting – as a parent or as a teacher. To listen to your hope for the future be praised or blamed by a jobsworth who probably hasn’t as broad an education or as much life experience as you.

Or to listen to a pushy parent, convinced their little tyke is a genius, and that the fault for any deficiencies the scamp may manifest is to be placed firmly at your door. That’s the difference between school when I was going through it, and school now: back then, parents deferred to teachers, and sat there and took it; nowadays teachers are constantly on trial by parents, and everything their little darlings say is believed. Rate My Teacher? Nah, Rate My Student, more like; or, more’s to the point, Rate That Parent.

Again, I have personal experience of this phenomenon: my mother wouldn’t talk to me for a week after my educators informed her at one such confab that “He’s only using half his ability.” I wonder whose fault that was? The teachers’ or my mother’s? The school’s or my home’s? It certainly wasn’t mine, at that age.

ChildrenofMen

Children of Men

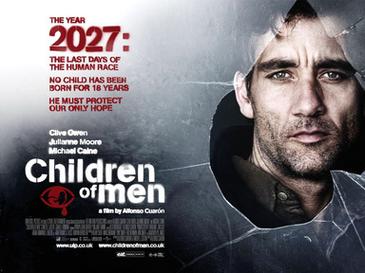

The literary and filmic genre most concerned with human extinction is dystopic science fiction. Alfonso Cuarón’s Children Of Men (2006) (based on P. D. James’ 1992 novel of the same name, with the addition of the definite article) envisages the world of 2027, when two decades of human infertility have left society on the brink of collapse.

The narrative arc of both book and film is a journey from despair to hope, sponsored by the notion that any such hope depends on the birth of future generations. Otherwise, all we can look forward to is despair, chaos and anarchy.

It is, in many ways, a modern-day nativity story, where the birth of a child is elevated to the status of The Coming Of The Saviour, who will redeem humanity from its many sins and vices. James herself has referred to her book as ‘a Christian fable’.

Denis Villeneuve’s Blade Runner 2049 (2017) (a sequel to Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner (1992), which was in turn based loosely on Philip K. Dick’s 1968 novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?) makes great issue of fertility as a prerequisite for, or at least an indicator of, humanity: the ability to reproduce makes replicants more human-like, and therefore more sympathetic and relatable.

Thus, if Deckard (whose standing as human/replicant is left ambiguous) has fathered a daughter with Rachael (a replicant), it renders the termination of replicants not only futile, but unethical and murderous. In the novel, the android antagonists can indeed be seen as more human than the human (?) protagonist. They are a mirror held up to human action, contrasted with a culture losing its own humanity (that is, ‘humanity’ taken to mean the positive aspects of humanity).

Klaus Benesch examined Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? in connection with Jacques Lacan’s ‘mirror stage’. Lacan claims that the formation and reassurance of the self depends on the construction of an Other through imagery, beginning with a double as seen in a mirror. The androids, Benesch argues, perform a doubling function similar to the mirror image of the self, but they do this on a social, not an individual, level.

Therefore, human anxiety about androids expresses uncertainty about human identity and society itself, just as in the original film the administration of an ‘empathy test’, to determine if a character is human or android, produces many false positives. Either the Voigt-Kampff test is flawed, or replicants are pretty good at being human (or, perhaps, better than human).

This perplexity first found an explanation in Japanese roboticist Masahiro Mori’s influential essay The Uncanny Valley (1970), in which he hypothesised that human response to human-like robots would abruptly shift from empathy to revulsion as a robot approached, but failed to attain, a life-like appearance, due to subtle imperfections in design. He termed this descent into eeriness ‘the uncanny valley’, and the phrase is now widely used to describe the characteristic dip in emotional response that happens when we encounter an entity that is almost, but not quite, human.

But if human-likeness increased beyond this nearly human point, and came very close to human, the emotional response would revert to being positive. However, the observation led Mori to recommend that robot builders should not attempt to attain the goal of making their creations overly life-like in appearance and motion, but instead aim for a design, ‘which results in a moderate degree of human likeness and a considerable sense of affinity. In fact, I predict it is possible to create a safe level of affinity by deliberately pursuing a non-human design.’

Brave New World

Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World (1932) paints a dire picture of society in 2540, rendered selfish, consumerist and emotionally passive through the (mis)application by a ruling elite of huge scientific advancements in reproductive technology (prefiguring that tabloid terror, ‘test tube babies’) and narco-conditioning.

But what if these grim prognostications about the disappearance of humanity, either literally or metaphorically, could be turned on their head? In fact, they have been. This horrifying dystopia could without too much trouble and just a little finessing be flipped into a much-to-be-aspired-to utopia, as Huxley himself attempted in Island, the 1962 revision of his more famous work.

This exploration of the possibilities opened up by biochemistry and genetic engineering for curing man, the sick animal, of his desires, violence and neuroses, sometime in the distant future, is taken up in more depth by Michel Houellebecq in The Possibility of an Island (2005). The distant descendants of Daniel have been culled from his DNA, with all the annoyingly rancorous human traits ironed out of the mix. So, we are transported to 2000 years in the future, where Daniel25, like the rest of these ‘neohumans’, passes his days in neutral tranquillity, adding his commentary to his ancestor’s personal history, striving to understand what could have made him so unhappy, while the remnants of the old human race roam in primitive packs outside his secure compound.

It’s a startlingly beautiful planet, Mother Earth. But we are royally fucking Mother Nature up, big time. We don’t deserve it, or her. An analogy can certainly be drawn between the harm humankind has caused to its own environment, and the harm that parents do to their own children. High time we terminated those relationships; or, at the very least, radically recalibrated them.

How do you explain to a child a world in which Donald Trump was the President of the United States of America for four years? And that his cabal of ghouls, grifters and vampires – many of them members of his own brood – held sway? And that seventy million people still voted for him a second time around? Worse, what if that child grows up thinking that state of affairs is somehow normal? Worst, what if s/he grows up into the kind of person who would vote for him or his ilk themselves, despite your best parental efforts at instruction, guidance or influence? That such people are even permitted to exercise the franchise, let alone allowed to breed, is deeply disturbing (because they would seek to curb your voting and reproductive rights). What if you, however inadvertently, breed one of them?

But, irony of ironies: to my father, I would be a failson, in terms of passing on his values and beliefs, the thing he held most dear: his Roman Catholic faith. Devotion to God sorted everything out for him, made sense of his world. God never meant much to me, after a certain age, except for the hassle encountered if you admitted to scepticism regarding his existence.

Donald Trump is a person who could have an infinitive number of pejorative adjectives affixed to his name, but none of them are necessary: everyone already knows what he is; yet many people voted for him regardless, either because they endorse this, or in spite of this. The same is true of Boris Johnson as Prime Minister in the United Kingdom, where 40 per cent of the British electorate will always vote Tory, no matter what! Tell that to the children. Or, given the questionable quality of the main opposition to either Trump or Johnson, try telling them that two-party democracy is somehow a good idea. Perhaps I am just losing it. Maybe I am at the end of my tether.

Have I missed out? Undoubtedly, parenthood is a common human experience I will not share. But I don’t feel particularly bad or bereft about it, especially when I look at the hassles of child-rearing, and the often fractured relationships and tensions between my peers and their offspring (although I will concede that I estimate that this generation is making a better fist of fostering good relations with their children than the previous generation did – a vast generalisation, I know, but something in the air due in some part to less authoritarian parenting styles. I’m thinking here about witnessing a good friend of mine taking a phone call from his thirteen-year-old son, and promising when prompted to send on a copy of Led Zeppelin IV for his boy’s delectation). I read in an interview with poet Michael Longley where he said that having children was the most profound thing he’s ever done, more so than all the poetry. But would I have felt the same way? There is no guarantee.

There is the question, already broached, of who will look after me in my old age? Peasants are supposed to churn out lots of nippers, as the kind of security provided by insurance policies. (Aristos don’t need as many, because they can already rely on their inherited wealth, which will be duly passed down to their heir and the spare, which was all that was necessary and sufficient for them to sire.) But these days, such indemnification is more likely to have relocated to Australia than to be on hand for your decay and demise. They could even predecease you. The idea that your children will be a comfort to you in your old age is at best a cosmic gamble – as is bringing them into the world in the first place. It is fruitless to speculate on whether or not your offspring can or will help to alleviate the indignities and sufferings of your senescence. Such mortifications, and how I manage them, may be something I am only beginning to find out. As I would have had to do anyway, with or without children.

If I had children, would I be writing this? No, and for more than just the obvious reason (that is, that I don’t have children). Odds on I’d be so busy looking after them and preoccupied about their welfare and their future that I wouldn’t have the time, energy or inclination to write at all (just as Sheila Heti speculates). Which leads to a further consideration concerning children as a form of sublimation for personal ambition, as a kind of compensation for lacks and voids and failures in your own life up until you have them. You may believe that they complete you, but is that fair on them? Or on the world? For whom, or for what, do these proud parents think they are doing a favour? The world, or themselves? Whatever their justification, the answer is neither, I suspect.

We were all kids once. Would we really like to go back there?

Maybe it all comes down to Eros and Thanatos. What if the death instinct is stronger than the sex instinct? It always is, in the end. Love doesn’t conquer all. It doesn’t conquer Death. Unless you are talking about what you leave behind, after your own extinction. For many people, for good or ill, that is their children. But there are other things you can leave behind. Even if it is only a form of negative space. I still regard my childlessness as almost unquestionably my greatest achievement. It is part of what I will leave behind. It is my gift to the world. I bequeath to all my unborn children, imagined and unrealised, forever unsullied and unfulfilled, mercifully untainted by human existence, all my Love.

Feature Image: Three daughters of King Lear by Gustav Pope