Build me a cabin in Utah

Marry me a wife, catch rainbow trout

Have a bunch of kids who call me “Pa”

That must be what it’s all about

That must be what it’s all about

Bob Dylan, ‘Sign On The Window’, from New Morning (1970)

When I was eighteen, during a summer spent working as a bus conductor while waiting on Leaving Certificate results, I thought I’d got my then girlfriend pregnant. Through a warm, endless July, she crept from two to three to four weeks ‘late’.

Finally, one evening, a phone call came with the good news that she was happily surfing the crimson wave, and there was great relief all around. It must have just been prolonged exam stress, we agreed. But the strange thing is, while obviously not quite ready to be a father then, I have never really been as open to the possibility of parenthood since.

During the extended period of waiting for her period to arrive, we discussed what we might do if worse came to worst. She contemplated an abortion – a big deal in Ireland in 1979, even if she was, rather too neatly symbolically, nine months older than me, and already in college; as was, if you can believe it, the very fact of having premarital teenage sex itself – while I was prepared to abandon all immediate plans for further studies and instead get a job to support her and our offspring. Never such innocence, or foolhardiness, again. It must have been Love.

Throughout my twenties, I hardly ever gave much thought to reproduction, unless it was as to how to forestall it. Of course, there were girlfriends, but I was never with anyone with the underlying agenda of ‘getting married, settling down and having a family’ (or any combination thereof). That was something I put off, along with having a proper career, until my thirties – if at all. The procreative function of sexuality would have come a severely poor second to the pleasure involved, and its pursuit. Enjoy yourself while you’re young. (Or at least give it your best shot.) You won’t be young for ever. (So get your kicks before you get too old.) You can’t have fun all your life. (So have as much as you can now.)

Perhaps such attitudes are not so unusual among the under-thirties, and even more so now than then (in the 1980s’). Yet, as I approach my sixtieth birthday, and having even experienced the establishment of a stable relationship which led to marriage, I can confirm that this viewpoint has still not changed significantly and, if anything, has only solidified into a worldview.

While my sexual needs may be marginally less clamorous than they were when I was a younger man, it is time to make the bald, bold declaration: the urge to replicate one’s genes is an impulse I don’t understand. The reflections that follow are an attempt to understand why that might be, to unravel the reasons for this mindset within myself, in the context of the culture which surrounds me.

Extraordinary Lengths

Walk down any street, enter any populated space, public or private, go anywhere where there are people: almost every person you see is the result of an act of sexual intercourse, and a subsequent pregnancy and birth. Propagation of the species is clearly popular. Or, at least, sex is. Multiplication/That’s the name of the game/And each generation/They play the same.

Some people go to extraordinary lengths to have children, if they find it doesn’t come easily, what with the rigours and disappointments and sometimes multiple pregnancies associated with IVF treatment. Observant Christians, Muslims and Jews will all tell you that their God commanded them to “be fruitful and multiply”.

Indeed, for strict adherents of the Judeo-Christian and Islamic traditions, procreation is the only function of sexuality, and sex for its own sake, much less as a good in itself, is sinful. Atheists will argue that child-bearing and child-rearing are more basic than that: they are biological imperatives. The drive to reproduce is part of how scientists define living matter.

Why do I not feel this biological imperative? It is, apparently, the most natural thing in the world. So why do I feel such a general indifference, and even a personal aversion, to the concept? And in how much of a minority am I, in this regard? But also, conversely, if the topic doesn’t really matter all that much to me, why do I care enough to spend time thinking about it, and go to the bother of trying to write something cogent about it, in the first place?

My choosing, or at least accepting, a child-free existence must worry me, at some level, if I feel a need to defend my position. Is that because it has now become part of my biography, even my identity? Perhaps, but the more obvious answer probably lies in the familial and societal pressure and expectation that one will reproduce (“Do you have any kids (yet)?”), and should very much want to reproduce.

This ‘to do’ list approach to human existence – albeit the result of cultural mores, religious teachings, socially engineering legislation, economic necessity or prosperity, and a myriad other prisms through which it can be viewed – becomes internalised, no matter how unconcerned with or questioning of society’s norms and agendas one regards oneself as, and is by all accounts felt even more intensely by women than men. (Forget about the biological imperative, what about the biological clock?) But a little reading around reveals that the naysayers are no longer such a tiny minority, if they ever were. To be anti-natalist is not to be unnatural. Nor is being child-free.

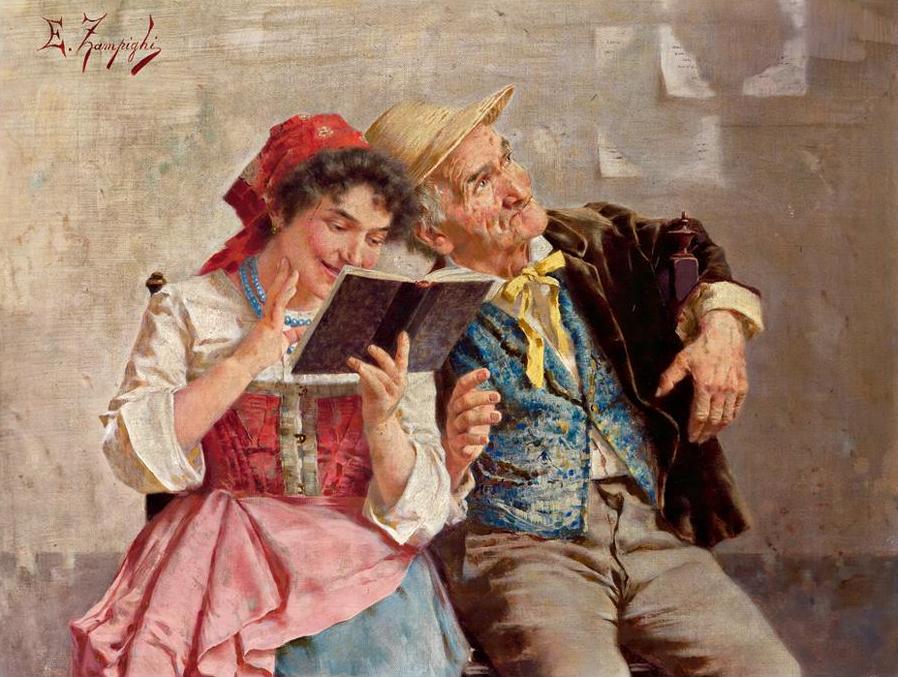

Eugenio Zampighi

Misanthropic and Philanthropic

Before we go any further, and risk becoming mired in ambiguity or contradiction, let’s define our terms, and where I would locate myself in the current state of the debate. Being ‘child-free’ (as opposed to the involuntary ‘childless’) is a choice that could be made for financial, physical, emotional, or any other number of reasons, whereas the more extreme ‘anti-natalism’ is a distinct philosophical position, as argued for by South African philosopher David Benatar in his 2006 book, Better Never To Have Been: The Harm of Coming Into Existence. Anti-natalists feel it is unfair to the children who are born and then left with the mess we leave behind.

There are two general categories of anti-natalism: misanthropic and philanthropic. Misanthropic anti-natalism is the standpoint that humans have a presumptive duty to desist from bringing new members of our species into existence because they cause harm.

Ecological anti-natalism (sometimes called environmental anti-natalism) is a subset of misanthropic anti-natalism that believes procreation is wrong because of the inherent environmental damage caused by human beings and the suffering we inflict on other sentient organisms.

The Voluntary Human Extinction Movement is representative of this type of anti-natalism. Philanthropic anti-natalism is the position that humans should not have children for the good of the (unborn) children because, in bringing children into the world, the parents are subjecting them to pain, suffering, illness and, of course, eventual death. Why become a cog in this endless cycle? Of course, there is a lot of room for misanthropic and philanthropic anti-natalism to overlap.

Furthermore, far from being the purview of some weirdo outliers, this essentially tragic worldview is a perfectly respectable literary-philosophical tradition, espoused to varying degrees by writers and philosophers as diverse as Sophocles, Flaubert, Poe, Schopenhauer, Nietzsche, Lovecraft, Beckett, Cioran, Larkin, Peter Wessel Zapffe and the anhedonic Thomas Ligotti. (Season One of the HBO series True Detective (2014) drew heavily on Lovecraft’s and Ligotti’s pessimistic, anti-natalist philosophy, as expressed by the character Rust Cohle.)

In The Myth of Sisyphus, Albert Camus posits that the only serious philosophical problem is that of suicide: having been born, is life worth living? One could counterargue that perhaps an even more serious philosophical problem is that of parenthood: rather than deciding whether or not to end a life that is already in existence, to decide whether or not to bring a life into existence in the first place.

Of course, most people don’t even give such a weighty problem a second thought. Or, if they do, it’s all part of their plan. Nor is it only men who can be less than enthusiastic about propagating the species, for social or personal reasons. Apart from obvious examples like Simone de Beauvoir – for whom marriage, child-rearing and family life represented a prison house for women – thirteen of the writers who contributed to Selfish, Shallow, and Self-Absorbed: Sixteen Writers on The Decision Not To Have Kids (2015), edited by Meghan Daum, were women.

More recently, Sheila Heti’s autofictional novel Motherhood is framed around a choice between having a child and writing a book. Exhibit Number One, regarding the outcome of this dilemma, is the object we are holding in our hands as we read. We should add the qualification that this dichotomous set-up is at best fallacious and at worst false, since many if not most writers – even female ones – somehow manage to do both. (How do they do it?) However, that the topic provides the focus for a bestseller is in itself noteworthy.

Eugenio Zampighi

To Each Their Own

Where do I lie on this scale? Well, what began as carefree child-freedom has probably hardened over time, and with some thought – as these things often will, into full-blown anti-natalism, roughly equal parts mis- and phil-. However, I should qualify the last assertion by saying that I am not prepared to go to war with anyone who fervently wants to have children: to each their own.

I am not about to undertake a crusade, or even launch a campaign, against those desperate to reproduce. I have never understood people who want you to be like them, or do as they do, who elevate their personal preferences into a modus vivendi for all.

I would only question their choices and beliefs to the same extent that they would question mine. The basic tenet of anti-natalism is simple but, for most of us, profoundly counterintuitive: that life, even under the best of circumstances, is not a gift or a miracle, but rather a harm and an imposition. According to this logic, the question of whether or not to have a child is not just a personal choice but an ethical one – and the correct answer is always no. So, if genuine anti-natalism means opposing all births, under all circumstances, then I am still of the merely child-free persuasion. I don’t necessarily consider all procreation to be unethical: I just believe in the individual’s right to choose.

I have had personal, up-close experience of this pressure to propagate, as applied not so much by my parents – as is generally the case – but by an ex-sister-in-law, and a brother-in-law.

Aged twenty-six, I had brought my then girlfriend, an Italian woman I had met during a sojourn teaching there, back to the homestead for a visit. In our sitting room one evening, in front of said girlfriend, then sister-in-law chose to launch into what she probably thought of as a homily, but I took to be a tirade, about how I should settle down and start a family, as though this was the only possible course of action now open to me. (Said lady had in the past opined, “I don’t want people like you teaching my children” – although I never quite worked out what was meant by ‘people like me’.)

She even went so far as to culminate in querying indignantly, “What do you believe?” Is there really any sane, let alone succinct, counter to this line of inquiry? Did she think she was establishing some sort of solidarity with my girlfriend? Similarly, when I was in my forties and married, my brother-in-law, of the fundamentalist evangelical Christian persuasion, while doing some tradesman work in the house I shared with my wife, started pontificating about the necessity of having children if you are married.

One is, it seems, not respecting the sacrament of marriage if one doesn’t. I subsequently complained to my sister about her husband’s behaviour, not least about the upset it had caused my wife, and we didn’t see him again for a very long time. Again, I ask: why does everyone else want you to be like them? Is it because they feel threatened by, or envious of, other, different lifestyles? Or because they are so sure they are right? Because accepting the same burdens and responsibilities they have taken on will make you a better person (in their eyes, anyway)? Could it even maybe be because they are happy, or think they are, and they want you to be happy too?

My own reading of these events is that, given the severe socio-religious strictures against pre-marital sex, and the shame and suffering of pregnancy ‘outside wedlock’, I guess in early 1960s Ireland (and elsewhere), when these people were courting, the only way to have guilt-free sex was to get married; and so, given the lack of available contraception, as a corollary that meant no option but to have children – whether you wanted them or not. Hence the Irish Family. So these people became seriously invested in the nuclear family as a universal norm. They had no other choice, except abstinence; and they certainly didn’t want you having something they never had. Heaven forbid, you might even enjoy it.

‘The Surprise Baby’

From the foregoing, it will be surmised that my brother and sister are somewhat older than me. This is indeed the case: the brother is twenty-one years my senior, and the sister has seventeen years on me. I am the youngest of three, by a considerable stretch: the afterthought, the heart’s scald, perhaps even a mistake. (And colloquially, in some circles, ‘the shakings of the bag’. Although also known in Swedish, I’m reliably informed, relatively more benignly if not entirely unambiguously, as ‘the surprise baby’.)

My brother and sister have four kids and six kids respectively. Looking back, I can see now that maybe my place in this familial structure took the onus off me to continue the lineage, and even that my own lack of motivation to have a family could have been an equal and opposite reaction to their extreme fecundity. I also retrospectively realise that, despite my parents’ relative reticence, the act of my bringing a girl home signified to them that my ‘intentions were honourable’, and that I was probably serious about marrying her.

Now that this essay has taken an unfortunately autobiographical turn, I recognise that the psychologists in the audience (both amateur and professional) will look to my childhood and adolescence, and my experience of being parented, as a revealing explanation for my indifference to procreation, rather than my having a genetic predisposition towards a certain frame of mind and worldview.

Maybe it’s how I was nurtured, rather than my nature? Perhaps they may even be right. Was my mother a monster? Did my parents have a fractious relationship? Were they neglectful, or did they regard their issue as a luxury they could ill-afford? While I recoil at the prospect of making this meditation on childlessness all about me, it occurs to me that I would have to field accusations of evasiveness were I not to engage with how my own formation has influenced my current thinking.

My father was twenty-four when my brother was born, and my mother was twenty-one. They were twenty-nine and twenty-six, respectively, when my sister came along. They were forty-five and forty-two when I rocked up. Do the sums. That is quite a chasm in the so-called generation gap. In fact, it is more like two generations, and growing up with my parents was a little like the reported experience of many people who are reared by their grandparents: they may love you, but they don’t exactly prepare you for dealing with the contemporary world, or help you to negotiate it.

Of course, as a child you are not aware of such anomalies at the time, and even into adolescence and adulthood you mostly just try to get on with things and play the hand you’ve been dealt.

It is only very gradually that the singularity of one’s own background becomes apparent to oneself, and can be crushing. It many ways, it is a lifelong, ongoing, realisation, constantly refined into old age. We are all works-in-progress.

Not that my parents were especially old school. In many ways they were more liberal than my brother and sister – who as young parents themselves, married and gone from the family home and starting their own families by the time I was four, were already becoming responsible authority figures, according to their own lights. Actually, it is more appropriate to write of my father and mother as separate entities, since they never exactly operated in tandem.

My father was traditional, conservative and dogmatically religious; but he was also kind. It is difficult to conceive of today, but he organised annual pilgrimages to Knock shrine for his colleagues, the busmen of C.I.E. He was praying the rosary in the front room while I was listening to The Sex Pistols in the kitchen. It broke his heart when, in my early teens, I announced that I didn’t want to go to Mass anymore.

My mother was a reader, and therefore could possibly be described as more open-minded and, if nothing else, she probably helped to inculcate in me a love of literature (although, curiously, not music – at least not the kind of music I was interested in: rock’n’roll was the work of Satan, and she put as many obstacles as possible into my path when I was trying to pursue a career in it; of course, she may well have been right, in that rock’n’roll is the Devil’s music, at any rate it is if you are doing it right – but she saw this as a bad thing, while I thought it was great), but she was domineering, exigent, and prone to exaggeration (‘The Queen of Hyperbole’ I dubbed her); she was also strict.

She was creative – a brilliant knitter and designer – but, like many intelligent and talented women of her generation, frustrated by domesticity, even if she would never have admitted it openly, or even to herself. Plus, we were working-class and poor, with the concomitant money worries and lack of opportunity and limited horizons.

As well as not having economic capital, there wasn’t much social or cultural capital knocking around either. Neither of them had got beyond primary school. I’m sure they’d had hard lives, struggling to make ends meet, with a boy born in 1939 and a girl in 1944, neatly parenthesising the privations of the Second World War, which continued into the dour 1950s.

However, while for a small child any given reality is accepted as normal and taken for granted, looking back from an adult vantage point, with some experience of observing other parent/child relationships, I would define my mother as simultaneously both distant and overbearing – or overbearingly distant, or distantly overbearing.

There is some history here: while expecting me, she moved out of the family home and decamped to a damp flat above Walton’s Music Shop on North Great Frederick Street, Dublin, taking my brother and sister with her (thus disrupting the former’s accountancy studies), apparently amid accusations from my father concerning her ‘clandestine inclinations’ (my old man had a very superior vocabulary, for a busman), the implication being that I wasn’t his child.

I suspect this was a complete fabrication on my mother’s part, although he would not have been above fits of jealousy. More likely (and for reasons I don’t fully comprehend), he was shamed by ribbing from his work colleagues about becoming a father again aged forty-five. Or perhaps it was these co-workers who, for a laugh, planted seeds of doubt in his mind regarding her fidelity and my paternity.

While these complexities are shrouded in mystery and the mists of time to me, accessible only through often conflicting second-hand retellings, it is certain she did have some cause for grievance. It is acknowledged that he would come in late from work when the rest of the family were in bed asleep, and bang around the kitchen making as much noise as possible, all the while taking protracted silences with his spouse when they did happen to meet up. (Joke: it was a typical Irish marriage – they spoke to each other once a year, whether they needed to or not.)

But then again, apart from his workmates preying on his insecurities, maybe he had his reasons too. As a simple working man, maybe he would have just appreciated having some dinner left out for him, after working double-days on the back of a bus. Taking silences was also my mother’s métier, for expressing her frequent displeasure, again alternating with loud, vehement outbursts of anger. I was much subjected to this parenting method, even as a small child.

Eugenio Zampighi

‘Dutch Uncle’

Guilt came early, and was ladled from a great height, for anything construed as misbehaviour – like innocently being too boisterous when playing with my nieces and nephews. It was as though she always, sometimes faintly and sometimes outrightly, disapproved of me at some basic level. (What did she expect an eight-year-old boy who didn’t get out all that much to do when said nieces and nephews were around? Just sit there in silence, minding my own business, or venturing occasionally to make polite conversation?) She talked to me, as she used to say herself, ‘like a Dutch uncle’.

I used to think the phrase meant someone who talked at length. Only recently did I find out that it is an informal term for a person who ‘issues frank, harsh or severe comments and criticism to educate, encourage or admonish someone…thus, a “Dutch uncle” is the reverse of what is normally thought of as avuncular or uncle-like (indulgent and permissive).’ But, predominantly, silence was the air she moved in, and its ambience extended to all and everything around her, at least when we were home alone together, which was a lot of the time. (Conversely, when in other company, and doubtless as a form of unconscious overcompensation, she could be loquacious to the point of tedium – there was rarely a happy medium.)

Dad was too busy working long hours, topped up with copious amounts of overtime, trying to keep the show on the road. She would quickly lose interest in being cooped up with a small boy for days on end. Consequently, I spent a good deal of time as a little lad in solitude, more than average for a child of that age, and was left to my own devices. I had to make my own fun. I was lavished with toys, but other humans – even those of around my own age – were strange, otherworldly creatures.

While I largely welcomed them when they invaded my world, I wasn’t always sure how to deal with them. (‘How do I work this new toy?’) Later, when I was around nine or ten, she went out to work, as a seamstress in the linen room of a hotel, and then as a general operative in a local pharmaceutical factory, and my aloneness was complete.

I came home every day from school to an empty house. But my mother’s greatest sin, as an extremely manipulative individual, who fought strenuously to control the family narrative (in which my role was to become the rebellious bad boy) was that she sought to turn me against my father (easily enough accomplished, due to his long, work-related absences and her being the chief caregiver – when the humour took her), but then later and depending on her mercurial moods, as if by fiat, she would blame me for disrespecting him. Being a powerless pawn caught in this crossfire between the king’s limited movement and vulnerability, and the queen’s infinite space and resources, would be enough to wreck anyone’s head. I was just another means for them to get at each other in their ongoing war of attrition, collateral damage in our bizarre love/hate triangle.

I’m thinking of Raymond Carver’s very short short story ‘Popular Mechanics’, in which an argument over custody between a departing husband and his wife concludes thus: ‘She would have it, this baby. She grabbed for the baby’s other arm. She caught the baby around the wrist and leaned back. But he would not let go. He felt the baby slipping out of his hands and he pulled back very hard. In this manner, the issue was decided.’

Christmas Morning

A memory, of Christmas morning, when I was aged about ten or eleven. The scene, my sister and brother-in-law’s house, where my mother had decamped for the duration, with me in tow, in another of her flits from my supposedly tyrannical father. I remember her eyes on me, watching me as I opened my presents from Santa, and I was conscious of the obligation to perform happiness and joy for her, because she was having such a sad life, and as her young dutiful son I was obliged to cheer her up.

It struck me, even then, that this was not how most of my contemporaries were required to behave, and it marked me apart. But there was always something performative about my mother, and those interacting with her. She spoke frequently of Love, but she used the apportioning of it as a form of punishment and reward. She constantly felt that others – not least her youngest child – should strive to gain her approval. In turn, I felt a constant pressure to show that I was having a happy childhood, and an equal pressure not to be any trouble – at least until adolescence hit.

This giving and withdrawing of affection, a constant tightrope walk of appeasement, has definitely made its mark on the quality of my adult relationships, especially with women: I associate people loving me with people wanting something from me, and with it arbitrarily being taken away if they don’t get what they want. Perhaps this experience of love is not so different from most people’s – for how often is any love offered unconditionally?

It is, however, one of the foundational and enabling myths of parenthood that parents are supposed to love their children more than themselves. But how many do? My mother did not love me more than herself. Maybe my father did. If work is love in action, he certainly slogged his guts out to keep us in the comfort to which we had no right to become accustomed. She, on the other hand, far from providing unconditional love, instead veered towards viewing me as a needless vexation and a thankless nuisance.

I can see now that, as a good-looking and quick-witted young woman, my mother thought she could have done much better in the marriage stakes, but she had been cajoled by her parents into a very early alliance with my father, because he was a kind man and they knew he would do his best to look after her. Which, understandably, wouldn’t have made my father feel great, especially since she was the love of his life.

Did I mention that she’d given birth to a stillborn girl, carried to full term, a year or two before I was born? She hadn’t expected me to live. When I was born healthy, and did live, I was ‘a miracle’. But then she had to deal with the consequences of this miracle. She left the grubby flat in North Frederick Street, diagonally opposite the Rotunda Hospital where I first saw the light of day (damn, my real dirty little secret is finally out: although I was bred on the Southside, I was born on the Northside – which side of the river is more opprobrious I will leave it to readers, informed by their own personal prejudices, to decide), and returned to the suburban council house I was brought up in, because it had taps with hot running water.

Did I also mention that she fell ill with double pneumonia after I was born? My seventeen-year-old sister looked after me for the first few months of my life – fed me, burped me, changed my shitty nappies, all the things it is assumed mothers do with their new-borns. I have the impression that my mother never bonded properly with me.

Despite her previous maternal experience, she didn’t know how to be around me. To a degree that was unhealthy, she wanted to be wooed – by her son rather than by her husband. Or, failing that, she wanted to be placated. I harbour the notion that my mother harboured the notion that she would have had some great second act to her life, had I not been born.

I also harbour the notion that she was suspicious of those who had ‘notions’ – especially her children – because she had never been given the opportunity to indulge her own notions. She embodied avant la lettre, and would certainly have been an enthusiastic appreciator of, The Cult Of The Difficult Woman. But, as Jia Tolentino astutely argues in her essay of that title, these days it is not so difficult to be a difficult woman. Be that as it may, I can categorically state: as a very small child, having a disappointed menopausal and/or post-menopausal mother, is not a good thing. And not just not good for the child, but also for the mother.

I very much doubt my mother was up for the sleepless nights, and the many other demands of child-rearing, at her age, in her delicate state of health, and having done it all before and thought it was all over. I was not, as a psychiatrist once asked me – clearly ignorant of the history of access to contraception in Ireland, due in no small part to the acquiescence of her profession in the machinations of the great church/state sponsored lie – a planned pregnancy.

Candidates for Divorce

If you love someone, you want to have children with them, it is said. As will be surmised from the foregoing, in my opinion, if my parents had been living now, and been more solvent, they would have been prime candidates for divorce, and very likely much better off for it. Or, at least, I would have been. During a discussion between the Ma and me on contraception and the ‘risks’ of pre-marital sex (still a hot topic in the early 1980s), she informed me that I was the result of ‘one lousy intercourse’.

Somehow, I don’t think I figured greatly in her plans. In a similar disquisition on the whys and wherefores of abortion (although now at long last safely legal in Ireland, still something of a red rag to a bull in some quarters) she revealed, “You could have been an abortion”, to which, if I’d had enough presence of mind, I should have countered, “Well, if I had been, I wouldn’t have known about it.” (Echoes here of the perennial cri de coeur of teen angst: ‘I didn’t ask to be born.’) What things for any mother to say to her son!

I have heretofore been ashamed of airing these exchanges for public consumption, possibly in an effort at blocking out the damage they would have done to the still evolving me, and a refusal to acknowledge how singularly and egregiously brutal they were. After all, the first love in your life is supposed to come from your mother. But I am ashamed no longer. I am too old now for it to matter what other people think of me, or of my mother, or of our troubled relationship, or of her memory.

Apropos: I am writing this as personal memoir because if I tried to write it as fiction, no one would believe it. I am used to not being believed. You decide whether or not you believe me now.

Defining ‘Natural’

Was my mother ‘unnatural’ in her attitude to motherhood? Well, that very much depends on your definition of ‘natural’, doesn’t it? In this regard, it is instructive to quote from Laura Kipnis’s essay in the aforementioned anthology, Selfish, Shallow, and Self-Absorbed: Sixteen Writers on The Decision Not To Have Kids, entitled ‘Maternal Instincts’:

…despite my proven talents at nurturing, I don’t believe in maternal instinct because as anyone who’s perused the literature on the subject knows, it’s an invented concept that arises at a particular point in history (I’m speaking of Western history here) – circa the Industrial Revolution, just as the new industrial-era sexual division of labor was being negotiated, the one where men go to work and women stay home raising kids. (Before that, pretty much everyone worked at home.) The new line was that such arrangements were handed down by nature. As family historians tell us, this is also when the romance of the child begins – ironically it was only when children’s actual economic value declined, because they were no longer necessary additions to the household labor force, that they became the priceless little treasures we know them as today. Once they started costing more to raise than they contributed to the household economy, there had to be some justification for having them, which is when the story that having children was a big emotionally fulfilling thing first started taking hold.

All I’m saying is that what we’re calling biological instinct is a historical artifact – a culturally specific development, not a fact of nature. An invented instinct can feel entirely real (I’m sure it can feel profound), though before we get too sentimental, let’s not forget that human maternity has also had a fairly checkered history over the ages, including such maternal traditions as infanticide, child abandonment, cruelty, and abuse.

I might add, similarly, that belief in a God or the gods was rather more popular in the past – and, in fact, for most of recorded history – than it is today. All life comes from God, the believers tell us: that is why they are ‘Pro-Life’. Are we contemporary godless atheists somehow, then, wrong?

My mother would have looked askance and jeered at today’s required standards of parenting. One time, when I was around twenty-two, she presented me with an itemised bill she had taken the trouble to compile, for how much it had cost to rear me.

It was high time I started paying it back. “There’s no return in you” was a common theme. Do I not have kids because I thought they would have cost me too much, because I could not afford them? “We did our best for you,” she told me another time. And perhaps they did. “I reared two gentlemen and a lady,” the Da would often boast. Except you don’t need to be well-off to praise and encourage your children. You just need to love them, and want what’s best for them. Never mind loving them more than yourself.

Featured Image: Idyllic Family Scene with Newborn by Eugenio Zampighi (1859-1944)