Automation in a variety of sectors could liberate millions from mind-numbing labour. But despite technological advances workers’ earnings have stagnated since the 1990s, while the rich have grown seriously richer, as we face an unemployment cliff. A powerful remedy to the impending obsolescence of many types of work, and grotesque inequality, could be the introduction of universal basic income. This would provide an unconditional payment to every citizen sufficient to avert poverty, providing an opportunity for individual flourishing, to the ultimate benefit of society. Another appropriate response would be for the law to require all companies to register a defined social purpose, beyond simply the exploitation of opportunity for profit. That way the dynamism of entrepreneurship might be harnessed for the common good.

With irresistible force the alien sound of an alarm bleeds into my dreamscape. A hand shoots out clumsily in search of the offending contraption – an aged radio alarm clock spilling the flotsam and jetsam of morning news. Woe is this man on a chilly January morning in Dublin! Then silence, as a finger brings a relieving click to the harangues.

I hide in the womb of my duvet, cowering before the frigid lash of cold air beyond the covers. Plea bargaining begins in earnest: ‘Another hour or two won’t make a difference’; ‘You aren’t productive in the morning anyway’; until finally the imperial self asserts: ‘To hell with this, I am going back to sleep’.

In response my whole being softens at the unexpected leniency, eyelids resume a stately repose, the pulse slows, and agitation of thought gives way to a free roaming imagination in slumber.

I have been resisting proverbial alarm clocks all my life, whether calling me to school, employment or binding exercise regime. I bridle – like other independent-minded people I know – at outside agencies determining my hours of sleep.

Last year, I was put on my mettle when I heard Leo Varadkar’s glib announcement on taking office that he wanted to be a Taoiseach for early risers. Like those guardians of the Ancient Roman Republic I sensed a Rubicon being crossed into my home territory by a recalcitrant general. The battle between dream and reality had been joined, and I would carry the Late Risers’ Manifesto into the affray.

It is out of stillness – not forcing our thoughts – that creation emerges. Silently, we assemble meaning, deconstruct artifice and forge originality. Brother David Steindl-Rast puts it thus: ‘Communication out of silence is true communication. All else is chitchat.’

I imagine internal remonstrances are not entertained in the intimacy of Leo Varadkar’s chamber. Excuses for softness, or indulgence of loitering are given short shrift. More likely: ‘Where is my singlet? I need to look sharp for the weekly vlog.’ He wastes no time on idle speculation, vacant imagination is held in check. The ephemera of newscast is devoured. Now attendants are called for. Primed for purpose – carpe diem – he seizes the day.

From workout to workday: the life and times of Taoiseach Varadkar. Photograph: Laura Hutton/PA Wire, https://www.irishtimes.com/polopoly_fs/1.3315569.1512416086!/image/image.jpg_gen/derivatives/landscape_685/image.jpg

II

Leo styles himself a liberal, preferring the state to leave the individual alone, a commendable notion for many situations, but not so where this allows accumulation of vast wealth by a small minority. Economic liberalism is predicated on a shaky assumption that success, measured in money, sex or fame, derives from a single-minded focus on hard work. Such fortune cookie philosophy would explain his veneration for the alarm clock, and attention to scapegoating ‘welfare cheats’ while a minister.

It’s a grand delusion that early rising and hard work make dreams a reality, at its extreme recalling the banner greeting Auschwitz inmates: arbeit met frei ,‘work will set you free’. A devotion to labour for its own sake is misplaced: it can have the effect of dulling the mind.

Adam Smith, the father of modern economics, asserted that the tedium of monotonous industrial tasks would render anyone ‘stupid and narrow-minded’; maintaining that the torpor of repetitive labour renders an individual incapable ‘of relishing or bearing a part in rational conversation’, or ‘conceiving generous, noble or tender sentiment’. He asserted that this would come in the way of ‘any just judgment concerning even the ordinary duties of private life.’

The Adam Smith Monument in Edinburgh.

Over the course of the last century especially, workers, including those engaged in monotonous ‘unskilled’ work, joined forces to win a series of improvements to their conditions. These included ample leisure time, giving scope for many among the proletariat to enjoy a reasonable standard of living. This permitted recreation along with access to higher education, a decent life followed for most of us in Western Europe. The decades after World War II are known as Les Trente Glorieuses in France and Il Miracolo Economico in Italy, as salaries kept pace with labour productivity. In large part this was down to the political clout of the Left, including Communist parties.

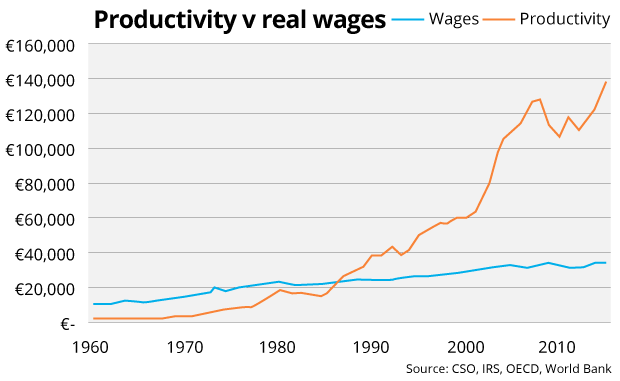

But these developments have given way to what is widely regarded as a Neoliberal Order. Since the 1990s real wages have stagnated, while private, and often public, debts have spiralled, with the wealth of a few expanding grotesquely. Tellingly, whereas in the 1950s the CEO of General Motors, then the model of a successful US business, was paid 135 times more than assembly-line workers, fifty years later the CEO of Walmart earned 1,500 times as much as an ordinary employee. Essentially, efficiencies enabled by new technologies are enriching those at the apex of corporations.

Unions, which were vital for bringing workers’ rights, are now in retreat. Those that remain often only represent employees in privileged positions. A chasm below an unemployment cliff looms in front of us, with little opposition to the new world order.

III

These developments are a feature of a technological revolution, especially in communications with the advent of the Internet, which is shattering a short-lived, post-Cold War consensus, and shifting the economic substrate. Moreover, the world wide web has rendered words, video and music virtually uncommodifiable, wreaking havoc upon the livelihoods of independent-minded writers, musicians and others artists, who struggle to share fresh approaches to life.

Automation looms in a host of industries which will further enhance ‘labour productivity’, at the expense of labour, and to the benefit of capital. The graphic below illustrates what has occurred in Ireland since the 1960s: from the 1990s productivity ceased to be passed on to workers.

Irish productivity per worker v. real wages since 1960. Source: https://www.irishtimes.com/opinion/david-mcwilliams-why-ireland-s-growing-economy-isn-t-making-you-richer-1.3327231

Our present disorder is comparable to the expansion of the Roman Republic in the first century BCE, when territories to the West and East fell to generals such as Caesar, Pompey and Crassus. These charismatic consuls pillaged unprecedented loot, bringing enormous prestige and popularity that led to an oligarchic triumvirate. This gave way to the Roman Empire in 49BCE, under Julius Caesar.

Today, we have our own benign despots of Big Data, whose loot would make an emperor blush. Their algorithms convey us from purchase to purchase, intruding ever more into our inner-most thoughts. Most worryingly, the independence of voting intentions are being severely undermined by sophisticated (anti-) social media devices.

At the outset of a dizzying technological revolution a small number of individuals wield unaccountable power, and as time passes the freedom of the Internet recedes. Just as the Celtic tribes of Gaul cowered before the ingenuity of Roman legions, structures of democratic government – states and transnational bodies – melt before the tortoise formations of the corporations, and their often solipsistic commanders. Of whom it might be said:

The sense that he was greater than his kind

Had struck, methinks, his eagle spirit blind

By gazing on its own exceeding light[i]

As in another age where the value of men was assigned in conquest, a capacity to appeal to a wide public with a new Internet tool, whether useful or not, has brought mind-boggling fortunes to the founders and shareholders of Google, Facebook, Instagram and the rest. There are few safeguards against truly villainous characters concentrating unassailable political power through vast fortunes. The descent of the Roman Empire into corruption and excess should be a warning.

Just as Johannes Gutenberg was buried in an unmarked grave while others profited from his invention of the printing press, opportunism rather than ingenuity tends to be rewarded under current economic structures; as with the phenomenon of Trump, who recalls the fiddling Emperor Nero himself. This acknowledged master of the soundbite is the product of inherited wealth, and the redoubtable political nous of Steve Bannon, who recognised the impending obsolescence of the American worker.

Yet it takes an outlier such as Bannon – whose final solutions I deplore – to lay down a challenge to our New Age consuls: ‘They’re too powerful. I want to make sure their data is a public trust. The stocks would drop two-thirds in value.’ Where are the mainstream liberals we might ask?

One such, Leo Varadkar, offers no opposition to the current order. Indeed, he unashamedly promotes dominant corporations in Ireland, through low, or non-existent, corporation taxation, which has long been justified by narrow national self-interest. We had an ‘Ireland First’ doctrine here long before Trump invented America’s.

The Irish state has been reduced to the role of croupier at a casino table where the super-rich trouser their winnings without being required to even tip the attendants. So obsequious is the Irish government that the award of an enormous windfall to the exchequer of the Apple tax bill is being resisted: ‘Would sir like to cash his chips in now or later?’.

IV

The impending obsolescence of much unskilled work may provide an opportunity for a fuller flourishing of homo sapiens. Liberation from tedious tasks, such as driving and manufacturing, should provide scope for the development of the “generous, noble and tender” sentiments referred to by Adam Smith. These resources may be shared with the Global South in time.

A powerful remedy to our present inequalities would be for wealthy federations such as Europe and the United States to introduce a guarantee of universal basic income: an unconditional payment sufficient for every citizen to avoid poverty. It could offer an opportunity for individual fulfillment in various domains, ultimately to the benefit to society. This would require, however, most states to improve educational and cultural facilities, which can be financed by effective taxation of assets, and simplification of codes.

An often parasitic financial industry must be regulated and taxed effectively, while the sustenance of life: especially a roof over one’s head, nutritious food, and public transport, must all become affordable; if not the cheap air travel to which we have grown accustomed. In many respects a Communist ideal, but with the major difference that the originality and drive of the entrepreneur should be harnessed

The Financial Crisis of the past decade originated in failings within the banking system, unconnected to what were, in fact, increasing efficiencies simultaneously occurring in the real economy. Rethinking economics in its wake involves questioning theoretical limitations on fiscal stimuli. The value we ascribe money currency is a product of the human imagination, and governments possess a singular capacity to generate more of it through expenditure.

Recent experience indicates that it is possible to expand the supply of money through our fiat currencies, without generating inflation. Thus austerity measures, which generally affect the poorest disproportionately are generally both unnecessary, and counter-productive. Optimum allocation of government resources should involve a weighting towards provision of basic necessities, which usually sees money being spent within a local economy.

Aligning policy to the basic needs of the population should be the role of democratic government, but this is often derailed by special interests. Socio-economic rights can be enshrined in European treaties so as to avoid a repeat of the disgraceful impoverishment of ordinary Greek people during the Crisis. But government expenditure must avoid the rampant inefficiency and careerism often found in the state sector, where people often stay in jobs out of fear.

The great error, and folly, of ‘Bannonism’, which Trump seized on for his peculiar policy of ‘America first’, is to assume that nation-states, even one the size of America, can mount barriers insulating them from the rest of the world. The racist idea of a chosen people singularly entitled to the good life is the source of much of the conflict in this world. We may respond positively to collective identities derived from mythology and literature, but these are imaginary concepts and ought to be acknowledged as such, rather than merged nonsensically with notions of biological inheritance. We are one people.

That’s my Steve.

V

One objection to the idea of basic income might stem from a pessimistic assessment that if not spurred by a need to work, homo sapiens will indulge his vices, especially excessive consumption of drugs and alcohol. Yet it is apparent that the oblivion of intoxication is associated with the end of the working week in jobs that do not inspire. It is also apparent that a sense of worthlessness generates excess, often self-destructive.

A legal right to economic security would take much of the fear, and even boredom, out of life, while affording the possibility for many to follow their dreams. The pursuit of money as an end in itself, is a lust for power held in common with the warlords of yore. Such moguls are a rare breed requiring containment (who in their right mind would have the motivation to become a billionaire?), and perhaps even compassion.

Naturally, many of us enjoy the regularity and community of daily work. That is nothing to be ashamed of, and there are numerous roles which will survive the technological onslaught, preserving the satisfaction derived from tasks well done. Home-makers, farmers, carers, and teachers of all kinds will always be required. The pleasure of craftsmanship and joint enterprise can be enhanced, so as to generate greater pride in work. Goods produced in an ethical and sustainable manner should be encouraged through targeted subsidisation aimed at reducing waste.

Technology professionals are particularly prized in our economy, and their continued usefulness is assured. Many wish to devote their talents towards altruistic goals, rather than work for vampire corporations, which exploit people and the Earth. The model of the open source linux operating system – such I avail of in this programme as I write – shows how a spirit of cooperation endures to make technology a collective resource.

We might also contemplate a radical shift in company law. The inherent danger of profit-seeking corporations was once widely recognised. Thus, between 1720 and 1825 it was a criminal offence to start a company in England, during a period of rapid economic expansion. In the United States until the nineteenth century there were two competing ideas regarding the purpose of companies: the first involved those with charters restricted to the pursuit of objectives in the public interest, such as canal building; the other regime issued charters of a general character, allowing companies to engage in whatever business proved profitable.

The latter category emerged triumphant, divorced from responsibility to fellow citizens, and often a unaccountable abstraction with separate legal personality. By altering the nature of the company under law we may continue to harness the thrusting energy of entrepreneurship for positive ends.

Acquisition of wealth is not the be-all and end-all for most of us, especially if basic needs are met. But we may still have a real dedication to what we do. Changes in company law requiring any company to have a public interest purpose contained in its articles and memoranda of association could prove hugely beneficial.

VI

Human creativity is manifest in a wide variety of fields. We may discover different vocations throughout our lives, some economically productive, others seemingly desultory, but perhaps crucial to individual development at particular junctures in life. The technologies we have developed should allow many of us to indulge our passions, which can ultimately be to the benefit of all, if creativity and invention are deployed in the right direction.

For many of us, the orthodox structure of the working day is unsatisfactory, and diligence occurs in pursuit of self-ordained objectives, rather than via external imposition This may seem like the privilege of an avant-garde, who tend to have enjoyed educational privileges, but many are increasingly imperiled by current economic structures, and wish to stand apart from what amounts to a conspiracy promoting the purchase of property.

We might draw wisdom from the lifestyle of the early modern craftsman, who was not beholden to a dictatorial clock, which has cast its shadow over the working day since the Industrial Revolution. Households would retire for a few hours after dusk, waking some time later for an hour or two, before taking what was referred to as a second sleep until morning. During this interlude, people would relax, ponder their dreams, or perhaps make love. Others would engage in activities like sewing, chopping wood, or reading, relying on the light of the moon, or oil lamps.

Nor was the working week set in stone, and the seasons would dictate the extent of one’s labour. Naturally, the number of burghers who dragged themselves out of a generalised misery at that time was limited, but those managing to do so could operate in tune with their own rhythms, not the demands of the omnipotent factory owner who emerged ascendant after the Industrial Revolution. In many respects the cooperative nature of linux programming represents a return to the model of the craftsman, as Richard Sennett has argued.

VII

The level of poverty we permit in our superficially developed societies is, simply, unconscionable. Insecurity and fear afflict far more than those living in destitution, and are the silent forces that drive us to the edge of reason. We have our winners and losers, but the number in the former category has declined considerably in recent decades, as the technological race stretches out the field.

Just as the Roman Empire grew out of economic imbalances resulting from conquest, our own societies confront unassailable capital, which feeds a delusion that chosen people can be saved from barbarian hordes.

The possibilities for homo sapiens are boundless. But we require basic safeguards to flourish. Companies can operate for the benefit of society as a whole, harnessing the dynamism of the entrepreneur, and working cooperatively as the craftsman once did. Let us avoid the fate of the Roman Republic, and prosper together.

[i] Percy Bysshe Shelley, Julian and Maddalo, (1819).

Frank Armstrong is the content editor of Cassandra Voices, www.frankarmstrong.ie.

Featured Image: Daniele Idini.