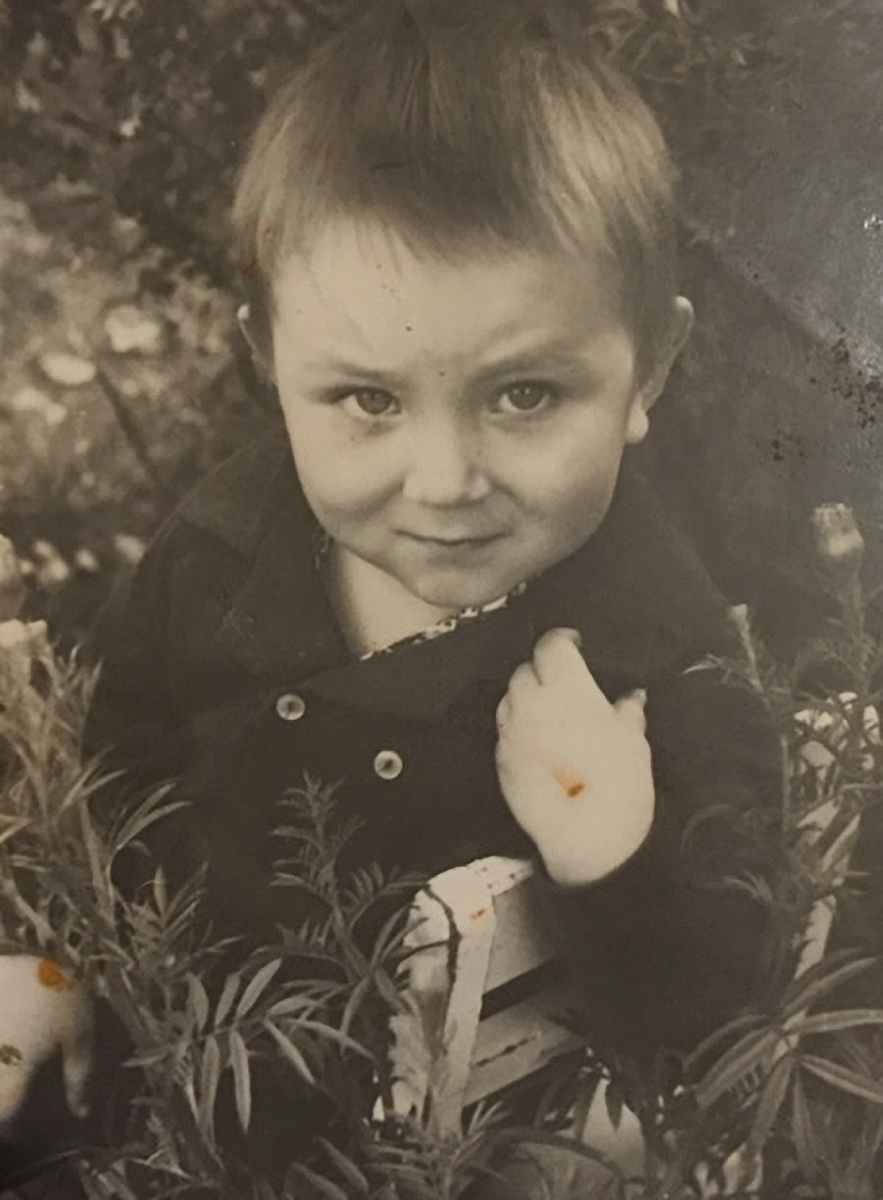

Prokopyevsk, 1974

SNOW is everywhere. So much of it, that the whole world looks like an old black-and-white movie. Through the grey haze, a pale and tired winter sun tries to warm the frozen land but only succeeds in turning water crystals into some kind of sparkling fairy dust.

Snow piles on double-sloped roofs like gigantic fur hats worn by Tartar warriors. It covers orchards and gardens with one unspoiled crispy sheet, broken here and there by naked trees and brush. Blackcurrant and raspberry bushes stretch crooked twig-fingers in a feeble attempt to gather some snow from the air as protection from the bitter cold.

Snow lies in huge mounds on the sidewalks where the cleaners have pushed it aside. Flakes of it fly in the air, which gives it colour and a shape resembling Grand-Dad Frost’s long silver beard to be tousled by the strong northerly gusts. Snow spirals up and off the tops of snowdrifts just as a desert breeze blows sand off the crest of dunes. But it’s not warm here, far from it. It’s freezing, and all things come alive if only to cloak themselves in the fluffy white mantle against frost-bite.

Snow Castle

I’m a real Siberian child, enjoying myself outside in sub-zero temperatures. Melted snow on my mittens cakes up into a layer of large ice diamonds. It’s impossible to brush them off now, as the ice clings to the wool fibres. I don’t really care though – I’m all covered in snow, from head to toe. But I’m not cold, having warmed up from playing with my friends, building a snow castle in an enormous snow bank built by the bulldozer at the side of my house. The castle looks more like a hobbit-hole, inhabited by four tiny, white, furry creatures, popping out here and there on the sides of a snowy hill.

It’s probably -25C. But so what? Our castle of snow is being invaded by evil mercenaries from the neighbouring building, two-storied and posh. But the castle belongs to our post-war barrack, mine and Anyuta’s. We live in the barrack and the castle is ours by God and all man-made laws. We won’t surrender it while we’re alive!

Anyuta is covering the north exit, viciously attacked by an older more experienced soldier, Ruler, while I deflect a heavy snowball bombardment from the south. Ruler thought he was very clever when he started the attack of the gate defended by a ‘woman’ three years his junior. Nasty bastard! But Anyuta proved to be a tough nut. She’s spun around in the narrow exit to kick Ruler with incredible energy. Her tiny ice incrusted woollen boots are called valenki. That round face, outlined by the fake fur of her pink coat’s hood, is so close to mine, upside down, laughing. Her big brown eyes are shining through the cloud of vapour like two ice-glazed cherries, cheeks bright red, lit by the cold and the fight.

I’m throwing back the snowballs to my red-headed opponent, Toast, trying to cover Anyuta’s exposed face. The fat Toast is as evil as Ruler, because he’s purposefully aiming at Anyuta. But I’m a warrior! I’m a knight! A bogatyr! I will save my sweet maiden and our beautiful home, even if I have to die in the battle. I’m picking up a snowball in each hand, springing up and running towards my enemy screaming “Huraaaaaah!”

Toast has not expected that. With the first snowball I knock his hat off and his red hair bursts like a flame among the all-consuming whiteness. The second snowball smacks right into his scarred cheek and he immediately pleads for mercy, because I’m already at his bastion. All his snowballs, which he was preparing so patiently before the battle, are mine!

“On your knees, you disgusting creature! Kiss my boots, as you surrender!” I say, pushing his red head towards my valenki.

“I’m already on my knees, you dope! Stop pushing my head! My ears are freezing!”

“Plead for mercy, and I will give you back your useless helmet!”

Toast starts crying and I stack his rabbit-fur hat on his flaming head. It immediately falls down and he’s not picking it up, hoping he’ll catch cold and it would be a perfect excuse for him not to go to the kindergarten in the morning. His grandma would be fussing around him day and night, feeding him like a piglet for slaughter and pouring hot tea with raspberry jam down his throat. Plus, he could always blame me for his misfortune.

“Typical Germans,” I grumble. “Just a little kick in the ass, and there you are, crying like a girl!”

“Yeah, right, I didn’t knock your hat off, did I? Now, if I get ill, it’ll be your fault, and I’ll tell my grandma you did it!”

“Well, tell her whatever you want, you sneak!” I reply defiantly, even though I’m not looking forward to Toast’s grand-mother’s visit to my home and accusing me of all the imaginable sins that a five-year-old boy could have done. I know that my mom would just laugh it off, but my granny would be very disappointed with me, and I hate when she tells me she’s disappointed.

“I’m not Fascist!”

”I’ll tell your grandma that you were throwing snowballs at Anyuta’s face. It’s a miracle you didn’t hit her, you nasty fascist sneak!”

“I’ll tell my grandma you called me a “Fascist!” I’m not a Fascist!” Toast started crying in earnest.

Anyuta and Ruler are standing beside us.

“Stop blubbering, Zhenka,” says Anyuta, “he didn’t do anything bad to you!”

“He knocked my hat off!”

“You’re such a sissy!” says Ruler. “If you keep sniffling and go complaining, we’ll never play with you again. And when you go to school some day, everybody will know you’re a sneak and a traitor, and nobody will ever talk to you! Ever!”

Sasha, the Ruler, has already started school, and he was quite an authority among us, the kindergarten kids. He already knew how to count ‘til one thousand, and could even properly hand-write his name.

I could only count up to ten and print my name with huge crooked letters (even though I was pretty proud of my achievements and even intended once to print my initials with pee on the snow).

We’ve always liked to listen to his stories about the teachers, uniforms, broken pen-boxes and other kids in such an ‘adult’ institution as THE SCHOOL. Everything seemed to be so magical and appealing in his ‘grown-up’ world. We still have to wait for two years to enter that wonderland called THE SCHOOL and stop being called ‘kids.’

Toast has stopped crying as if a divine illumination had descended on him from the gathering snow clouds and the early winter dusk. The last rays of sunlight tinted the snow around us fuchsia-pink, like the magical blood of the fallen heroes who were fighting for our hobbit-holes (pardon, CASTLE) so bravely and now are no more.

We can almost see them, our imaginary knights, archers and common soldiers, dying in the field for our lord and ladyship’s honour and our home. Zhenya the Toast’s head is covered with fallen snowflakes that make his red flaming hair burn with an ominous pink sparkle.

“I was joking, you dopes,” he finally says, shaking the tears off his colourless eyelashes and putting his hat on. He realized he may indeed catch cold and it won’t give him any advantage now. “It’s so easy to scare you! Would I ever give my pals away? Is that how you think of me?”

“Friends then,” says Sasha the Ruler. “Peace to this beautiful unspoilt and unconquered castle! Long live the king and the queen! I have to go home now. The blasted Crow (his primary school teacher’s nickname) gave us loads of homework to do. Enjoy the potty training in your kinder-garten tomorrow.”

Little Germany

“I have to go too,” sniffles Toast. “My grandma will be awfully worried. It’s getting dark. Plus, she’s been cooking apfel-kugel today. Yummy!”

Zhenya looks like an apfel-kugel himself – all round and “toasted”. His red hair, freckles and a scar on his cheek make him resemble a plump, freshly fried doughnut, stuffed to the brim with the German delicacies his grand-mother fills him with all day long. Zhenya is not stingy – he brings his granny’s culinary production to the street in amounts that could feed a small battalion of the Red Army – and we all gorge ourselves on pies and sweets cooked according to the ancient German recipes.

Zhenya’s grand-mother is indeed German, but not one who was born in Germany. She’s Volga settlement German – eighteenth century.

Tsarina Catherine II signed a decree allowing foreigners who so desired to colonise unspoilt Russian territories. More than 30,000 Europeans were recruited, mostly from Germanic kingdoms and principalities. Most of those Germans and their descendants settled on the River Volga, living in their own communities unmolested until the Second World War.

Jealously they guarded their traditions, language and cuisine, carrying in their hearts a nostalgia for their forefathers, who’d left their homeland centuries ago to find happiness and prosperity in wild and cold Russia. In spite of having been born in their new ‘Motherland’, somewhere deep in their consciousness, they always missed their ancestors’ walks on the Rhine, Christmas Markets, mulled wine and roasted chestnuts.

But when the war broke out, ‘Little Germany’ attracted unwanted attention from Stalin. The Great Leader thought Germans on the Volga might easily side with the enemy – they were Germans after all – even though they’d lived through two centuries of Russian history and become as Soviet as anybody else in my huge country.

But their foreign blood made them potential traitors, and the whole settlement was sent to Siberia, the Urals and Kazakhstan, where they were thinly dispersed amongst the locals. Thus, my little town in the middle of nowhere, has real foreigners in its midst, speaking Russian in a German accent so thick, that we can hardly make heads nor tails of what they are saying.

I laughed to myself, when Zhenya’s Granny was telling my own babushka, that she finally bought herself a nice pair of sobaki – our word for dogs. When obviously she meant to say sapogi about her new boots. Evidently the subtleties of our so-called barbaric language eluded her, so uncorrected she carried on bragging about the warmth and comfort of her new winter dogs.

She comes to our humble home complaining about me. Because I bring her Zhenya to tears quite often. I call him a fascist, especially when he makes me mad. That happens a lot, because he is too girly, and one girl, Anyuta, in our company is more than enough. But to his face I’ve never called him ‘Toast’, ’doughnut’ or ‘fat-factory,’ because it would be a dig below the waist.

However, post-war, the fallout from fascism is still felt by all, and calling someone a fascist just because of his German heritage isn’t nice either. Toast’s granny detests the fascist label as much as he does.

But when she visits us for a chat with my grandma, and brings us a big slice of straight-from-the-oven apfel strudel, then I bless the Germans (and Germany) for remembering how to bake those delicious pies, and wonder where Toast’s granny gets apples in the middle of the winter.

The carrots I have at home are no match for her warm pie and its golden crust covered with melted sugar. Granny gives it all to me, wiping a tear from her eye; while, like a starved puppy, I lick its sweet filling from my fingers.

Once, when Zhenya’s grandma had just left, I proceeded to devour the pie my eyes had been feasting on for hours, and she sat beside me, stroking my hair.

‘Gemography’

“Eat, sweet child, eat. It’s not your fault we’re so poor. I wish we had money and connections to get you some bonbons or a chocolate bar. I wish your father came over more regularly and took care of you. But soon, you’ll grow up, go to school and learn how to read and write, even gemography…”

“I already know how to read, Babushka. They taught us in kindergarten! And it’s “geography”, not “gemography”. Ruler told us he will study geography next year.” I saw myself as practically a scientist, since I knew how to pronounce the word “geography”, and an adult like my grandma didn’t.

“Oh, that’s good! It’s so good indeed. You’re such a clever boy, Mishenka! Now, the school will be so easy for you! And then you’ll study hard and you can be whatever you choose to be! Imagine, you’ll be a doctor when you grow up? You’ll wear a white gown and a stetho … stethacope … that thing to listen to the chest. Everybody will respect you, and the people will greet you on the street “Good morning, Mikhail Gennadyevich”, and you will have your own office and a nurse … Imagine! You just have to study hard at school and get good grades.”

“I will, Babushka. Can’t wait to go to school! Can I go next year?” already seeing myself dressed in a white gown with a stethoscope around my neck.

“Not yet, sweetheart. You’re only five. Just wait for two years.”

“But why? I can already count to ten.”

My grandma hesitated: “You have to grow up a little. Otherwise the school desk will be too big for you. You won’t see what the teacher writes on the black-board.”

My dream of becoming a doctor soon burst like a soap bubble. I’d have to study first. On top of that, I’d have to wait for two long years before even beginning my studies.

So unfair! I turned back to the apfel strudel, finishing the remains of the slice in two seconds and started to feel sleepy, with the images still floating in front of my eyes: a white gown, a stethoscope, a blackboard (whatever it is in reality, but I see a black, charred by the fire board from a pirate ship), a doctor’s office and me there, behind the school desk.

Bride-to-be

Toast’s round shape, and Ruler’s tall and lanky one, start to disappear in the snowfall. It’s become a little warmer now, and snowflakes glide through the air like extra-terrestrial insects, waltzing around in their mysterious mating dance. They finish and die, covering the earth with their tiny bodies to protect it from the winter cold. The entire world is blanketed by their heroic sacrifice. I don’t know anything else beyond our barrack, orchards, kindergarten and the two-storied buildings where Toast and Ruler live.

Anyuta takes my hand. A year younger than me, I consider her a perfect candidate to be my bride when I decide to get married. She’s pretty, sweet, and she plays with boys, while other girls in the kindergarten only play with stupid dolls and don’t go out to the street without their parents

My grand-dad doesn’t like Anyuta. He calls her “little gypsy”, and says Anyuta’s mother is a “slut.” Trying to defend the lady of my heart and her mother, I told him once that I’m a slut as well.

“That boy is properly stupid! Honestly! Now, he’s a slut too!” he turned to my grandma. “I tell you once again, don’t let him play with that gypsy girl! She’ll be the exact copy of her mother! Mark my words.”

“He’s a child, for God’s sake. You shouldn’t use those words in front of him. What if he goes and says to Ninka “Good morning, Mrs. Slut?” What then? Are you going to explain to her where he heard the word and why he called her so?”

“She knows it herself that she’s a slut, your Ninka woman. Did you see her with a new tall guy the other day? She just dumps the little gypsy at her mother’s and jumps on anyone with a cock and a pulse,” my grandpa grumbles. “What else can you call her? Virgin Mary?”

“Don’t mention the Virgin Mary, for God’s sake! God forgive us,” my grandma made a quick sign of cross on her chest. “Please, don’t say that in front of the child again! There’s no need for him to learn all those words of yours!”

“He’s a boy! He’ll learn them sooner or later, won’t he? Especially if he keeps playing with that little gypsy girl,” retorted my grand-pa. “He doesn’t understand what we’re talking about anyway. Do you, Mishok?” He turned to me.

“Of course I do!” I was really eager to show my grand-dad that I’d already grown up. “I also have a cock! And Anyuta has a cunt!”

I rushed to demonstrate all the information I’d learned about sex from Ruler. He’d told us once, that both Toast and I had cocks so small, that we could do nothing with them but pee. That was how I came to comprehend that strange object on my body. Obviously aware of it, I didn’t know it was called a “cock”.

He’d also said that women had cunts which I interpreted as merely the absence of having a cock. Consequently, I’d undressed a doll in the kindergarten, confirming my theory that girls had indeed absolutely nothing there. Just a small hole at the bottom.

“Mishenka, my little boy, don’t say those words. There are bad, really bad. Only drunkards and criminals use them. You won’t use them, will you?” My granny looked like she was going to cry.

“I told you!” my grand-dad seemed to be pleased. “Little gypsy! She’s teaching him all this stuff. And these are only flowers – the berries will come later.”

Scared, I was sure I’d said something awful. Granny was about to cry and I hate seeing my grandma crying. I told myself, that I’d never ever use those words in front of her again.

An ugly beast

Anyuta and I stand in the gathering darkness in front of our barrack. She lives in number 6, and I – in number 1. There are ten one-room flats in total in this long, dark, red-brick building. The snow on the roof almost blends into the snowdrifts, as if the building is even bigger.

I don’t want to go home yet. Neither does Anya. The falling snow sparkles yellow in rectangles of light cast from the apartments. Above the half-curtain that covers only the bottom part of the window, I can watch Anyuta’s grand-mother cooking dinner.

Standing in front of her flat, I feel far away from my own home. Unable to see what my own granny is doing, I get a physical sensation of being miles away, in a raging snow-storm at the North Pole. I’m gripped by fear that I’ll be lost and because of me, grandma will cry with grief.

Anyuta is holding my hand. ‘We’d better make ourselves a house,’ she says. ‘I’ve never seen such a snowfall in my entire life.’ I agree. I’ve never seen such a snowfall either. I couldn’t even distinguish the windows of the barrack from the building now. What I saw resembled a series of pale suns secreted behind gossamer.

We walk towards the row of toolsheds built in front of the barrack. A sheet of freshly fallen flakes lay undisturbed, and clean ahead of us. Hand in hand; we’re knee-deep in the snow. Pioneers in uncharted territories, the first to spoil the virgin beauty of land that hasn’t known a man. At least today. The last wind left a snowdrift to tower in front of the sheds and for us it’s like the Himalayas!

When we approach the danger zone, at the gap between those sheds leading to the public latrines, Anyuta stops me with her hand.

“Let’s not go there. Mom says an ugly beast lives there and he has very stinky breath. Do you smell it?” She sniffs the air, but the usual summer stench can hardly be perceived in the freezing cold. “She says he likes to eat small children, especially girls!”

“I’m not a child, Anya! I’m five! And I’m a whole year older than you. You don’t even know what five means yet! You still show your fingers when they ask how old you are. But I’m a grown up man! Don’t be afraid, my princess, I will protect you!”

I know exactly where the stench comes from, because my mum tried to teach me how to use the latrine once. Petrified with fear, I refused even to approach a big gaping hole on the floor, full of excrement and flies.

But I don’t tell that to Anyuta. Besides, her mother may be right. The beast might live inside that stinky pit. I pull her a step forward, then, after a moment of thinking, I decide to make a snowball for good measure. ‘If the beast comes out, I’ll throw the snowball right between his eyes, and he’ll die forever!’

Easier said than done, though. I suddenly smelt the putrid stench of the latrine monster. Did someone cough out there, in the gap? Or roar? The snow is waist high and we’re so far from home! We can’t run fast either. We’re stuck in the snow. Scared, I see Anyuta’s eyes wide with terror. Has she seen the beast? Can the beast cast a freezing spell?

Anyuta’s tomcat, Shaitan, jumps out of the shed with a piece of sausage in his snout and dives into the gap. Something inside the shed falls down with a loud metallic clatter. In a split second, we see two bright green spots. Shaitan’s eyes are glowing in the forbidden gap, until he turns his head back, listening to the night. Everything returns to normality. The total silence, interrupted sometimes by a howl of the wind under the rooftops, and the barking of a dog somewhere.

Anyuta smiles.”Oof, Shaitan scared me breathless! I’ll tell my grandma now who steals her smoked sausages from the shed. She thinks mum drinks wine with her boyfriends there, and they eat the sausages for a snack,” she’s looked away.

“You know that Shaitan means ‘demon’ in Turkmenish? I saw it in a cartoon. I called the cat Shaitan, because he was scratching me badly even when he was a kitten. I love him though, when he’s not hungry. He can be very friendly. He doesn’t like when I pull his tail though. Or touch his belly.”

The Perfect Spot

We’ve decided not to climb the Everest, but walk around it, to the toolshed’s doors, where the wind, for some reason unknown to us, has blown all the snow away. And there, we’ve found a perfect spot for our home: the wall of snow makes a mountain on one side, the shed-door on the other, and the ‘snow-hat’ hanging from the roof above us.

It almost touches the peak of the Everest, and so it isn’t snowing here. It’s warm and cosy. We make a huge table on the mountain side, two cubical chairs, and as a final touch, I cut the window into the outside world. Anya starts ‘cooking dinner’ – snowballs with sugar, and I’m making cookies from the harder pressed sheet of snow I’ve cut on the side of the mountain. The cookies look so good! I rub them against the door to perfect them in the shape of stars, crescents and circles.

“How did you do that?” Anya’s brown eyes are again wide open.

“When you marry me, I’ll make these cookies for you every day. Even in the summer. I’ll find snow for you…”

I suddenly feel that I should kiss her and give her a snow doughnut as an engagement ring. She’s so near. I reach out and kiss her on the lips, like I used to kiss my mum before I grew up to the mature age of five. Anyuta’s lips were wet and covered with snot. I barely stop myself from spitting out and saying “Oof, yak!”

“Don’t do that again,” she says angrily, “I’m too young to be a mother! You know where all this kissing leads!”

I honestly don’t know. How could I?

“First, it’s all this kissing-wissing, and then – oops, you’re pregnant. That’s what my grandma said to my mom,” she explains patiently. “You can get pregnant from kissing, you silly.”

“Pregnant?” Even the word bewildered me. It sounded so funny.

“Yes! Belly with a baby! How do you think you were born? Found in the cabbage patch?”

Wasn’t I? Until this moment. My mum always told me, that as I was born in the middle of the summer, I was found among the cabbages on my granny’s orchard. She said she went out to bring a cabbage for soup, and found me, big, fat and pink, but with a head of long black hair. She always said that I was born with long black hair. However, the contradiction of “being born” and “found in the orchard” never bothered me until now.

“Do the men get pregnant?” I ask her trembling with fear.

“Mmmm,” she touches her chin with her mitten and looks up thinking. “I’m not sure…”

In shock now I realize, I’m way too young to be a mother as well. On the other hand, why are men called fathers? I’ve never heard anybody call a man Mother. Even though, Uncle Semyon has a really big belly. God, he must be pregnant. My heart sank. What will my grandma say when my belly starts growing? Why on earth have I kissed her? And Anyuta’s still trying to recall what her grandma said.

“I think so,” she says finally. “Do you think only we women have to suffer?” She takes my snow doughnut though. “It’s beautiful! Are those mini diamonds?”

“It’s just snow!” I immediately forgot about my little ‘pregnancy problem’, more concerned by an imminent slap from my grand-dad, when he finds out I’m having a baby.

“Snow is mini-diamonds, you silly. Look!” She catches a drifting snow-flake. “Look at it closer. Do you see how beautiful it is? It’s like a little flower, only pointy. Look!”

The snow-flake is indeed the most beautiful thing I have ever seen so far, and I immediately decide to immortalise it on paper for Anyuta. As soon as I get home, I’ll draw it!

“Mishenka, where are you, sweet kitten?” I hear my granny’s voice from far away. “Come home, child! It’s freezing cold out here!”

“Can I play a little longer, Bab?” I said sticking my head out of the improvised window to see granny, but the sash collapsed and our sweet home flooded with millions of mini-diamonds that smashed my childhood dreams. Still vivid. In snow.