Dervla Murphy’s father was one of Pádraig Pearse’s patriots. Schooled in St Enda’s, aged eighteen he was incarcerated in an English prison for three years, ‘sewing sacks for the post office, wretchedly fed and crawling with lice’, as she wrote in her autobiography, Wheels Within Wheels. The Murphys were anti-Treaty Republicans. Every one of the family was jailed ar son na cúise.

Her mother’s family the Dowlings, on the other hand, were terribly respectable, and wealthy, until her mother’s father, a drinker, fell into the Royal Canal and died. His wife, Jeff, happened to be passing when his corpse was lifted out. Maybe as a result of this trauma, Dervla’s grandmother Jeff retained ‘a tight-lipped aversion to pleasure, however innocent.’

But at the home of Dervla’s father’s people, in Charleston Avenue, Rathmines, ‘there was poverty too, but it was happy-go-lucky rather than gloomy and self-pitying,’ Dervla wrote.

When Feargus Murphy and Kathleen Dowling married they immediately left Dublin for Lismore, a remote and beautiful tiny town in the Blackwater Valley of Waterford. Feargus had been appointed county librarian, and immediately settled in to create literary centres out of country libraries. He founded Ireland’s first mobile library with the help of Kitty – the couple sometimes sleeping in the library van as they toured the county.

Lismore Castle, Co. Waterford.

Dervla was born in 1931. By the age of two, her twenty-six-year-old mother had been crippled by rheumatoid arthritis. After travelling to England, Italy and Czechoslovakia in search of a cure she returned to Lismore, a hopeless cripple whom doctors advised to avoid having any more children.

The family loved and cosseted their one fierce chick. Dervla spent time in Dublin with her mother’s people, the enduringly Unionist Dowlings, and with her beloved paternal grandparents and cousins in Rathmines. There she roamed a house filled with Pappa Murphy’s books and her grandmother’s endless bridge games. Pappa had been on hunger strike in England for six weeks at the age of forty-eight, dragging his health down, and Granny had also been jailed.

In Lismore, Dervla grew up with a healthy level of wilfulness. Among her friends were the neighbouring Ryans, a conservative family. She spent as much time in their home as in her own; their son Mark, an intellectual priest, became a second father to her.

At home, she was raised on her mother’s preferred diet for her only child of raw beef, raw liver, raw vegetables and brown bread, with four pints of milk a day, with no place for tea or coffee let alone fizzy drinks. Cooking could be problematic: at one stage Dervla and her father made dinners on an improvised electric cooker which he had repaired; they wore wellington boots to prevent fatal shocks!

For her tenth birthday received a a secondhand atlas from her Pappa, and a second hand bicycle from her parents. This combination brought the realisation one day as she cycled up a favourite hill near Lismore that she could actually get to India if she simply kept pedalling.

At twelve she was supposed to enrol in St Angela’s Ursuline College in Waterford – her aunt Kathleen wrote to her enthusiastically from Mountjoy Prison promising she’d love it – but on account of the circumstances of her mother’s illness and perhaps also the meagre pay of librarians in the new Irish State, this was not possible until 1944, when she was thirteen.

Dervla loved the school and thrived there, but by the following year a crisis had developed in Lismore. A series of housekeepers had nursed her mother and kept the ragged home together. But this situation could not endure, leading to a conference with her parents where three options were laid before her: Dervla could leave school and nurse her mother; she and her mother could go to live with relatives in Dublin where it would be easier to find help and Dervla could attend another school; or Dervla could return to school in Waterford and her parents could somehow soldier on.

The decision was left to the fourteen-year-old Dervla: ‘We had just finished dinner and I saw my father’s hand shaking as he lifted his coffee cup to his lips,’ she remembered. Of course she chose to leave school and look after her mother.

The Murphys in Dublin were incandescent at the decision. A cataclysmic row erupted leaving the family at permanent loggerheads. ‘As a result of our tribal warfare I never saw Pappa again,’ she wrote. A period of love and funniness had come to a sudden end.

Dervla became her mother’s full-time carer until she was almost thirty, nursing by day and by night an increasingly helpless woman. Even in the early stages of her illness she was compelled to manipulate knitting needles just to turn the page of a book.

The only respite for Dervla were long walks with Mark Ryan, the neighbouring priest, and long cycle rides. On one such, aged seventeen, she met a solitary Englishman who, like her grandfather and her father, had been imprisoned for the cause – in his case in a Japanese POW camp in Burma during World War Two. Godfrey and Dervla established a private companionship until his death in 1959 in London when she was aged twenty-eight.

She had been writing since childhood, but in these years she did so with greater discipline and intent. She completed a novel about an illegitimate girl growing up in a small Irish town, which she sent out to half-a-dozen publishers; one of whom hinted that a happy ending would make it publishable, but Dervla was not prepared to compromise.

At least Dervla gained some relief from her onerous duties with a few long cycling trips – to Wales and Spain, through Italy, France, Belgium, Germany – but her increasingly mentally ill mother’s autocratic insistence on perfect housekeeping brought on a complete crack-up.

Her mother passed away in 1961 and her father a year later. Then in the terrible winter of 1963, Dervla headed off on her bicycle Rozinante, with a meagre bag of supplies, a few quid and a pistol. She was on her way to India.

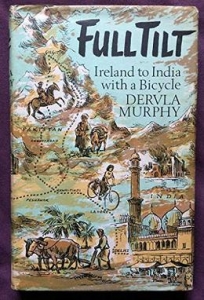

Her thrilling account of the trip, Full Tilt: Ireland to India on a Bicycle was snapped up by the prestigious British publisher John Murray. This was before the days of the hippie trail. Her journey had been unimaginably exotic (and yes the pistol did come in handy) as she cycled over the mountains of Pakistan, breaking her ribs, experiencing ravings after heatstroke, among other mis-adventures.

Dervla travelled and wrote about it for another forty years. Her books became classics in their genre. These covered work with the Dalai Lama’s sister in a camp for Tibetan refugee children that was a central experience in her spiritual life; riding a mule through Ethiopia, along with travels in Nepal, India, Madagascar, Peru, Cameroon, Palestine, Romania, Laos, and even Northern Ireland.

Dervla Murphy with Michael Palin in 2012.

When she gave birth to a daughter and brought her up single-handed, she may just have kicked out the first stones of the wall that then surrounded Irish women; this was in the age of Magdalen Laundries and Mother and Baby Homes. She demonstrated that a single woman with a baby did not have to be at the mercy of church and state and all-seeing respectability.

Dervla Murphy’s books have remained in print for longer than any other modern writer. She remains our greatest explorer, and a stirring voice of a liberal worldview that Ireland has only gradually accepted; a voice calling for a new world.

Lucille Redmond’s collection of stories, Love, is available on Amazon and on Apple Books