The appeal of exotic cuisines and esoteric diets has done little to diminish bread’s status as the primary foodstuff of the Western world, and many areas besides. Symbolic as the ‘staff of life’ and ubiquitous, the Oxford English Dictionary describes it in wholesome simplicity as a ‘well-known article of food prepared by moistening, kneading, and baking meal or flour, generally with the addition of yeast or leaven’.

But charges of adulteration have long been laid against the baker, the miller and the farmer. Today, more than ever, bread has departed from the purity of its essential elements: flour, water and usually salt for flavour. In the early modern era, however, fast-acting yeast, derived from brewers’ barm, began to replace the traditional sourdough leaven: simply flour and water containing a live culture similar to yoghurt. The addition of yeast was the beginning of a downward spiral culminating in today’s industrial loaves, products of the insidious Chorleywood Bread Process.

A list of the ingredients, wheat apart, of a familiar brand of sliced white bread reads like pharmacopoeia: Emulsifiers, E471, E472e, Soya Flour, Preservative, Calcium, Propotionate (added to inhibit mould growth), Flavouring, Flour Treatment Agents, Ascorbic Acid (Vitamin C), E920, Dextrose. Such bland uniformity and chemical defilement led the great cookery writer Elizabeth David to muse: ‘A technological triumph factory bread may be. Taste it has none. Should it be called bread?’[i]

The quality of loaves from an Irish market worth €1.9 billion in 2019 should be a matter of public concern, as the consequence for our health of inferior bread is devastating. Perhaps more importantly, the satisfaction derived from the breaking of quality bread approaches the divine.

Wheat

The most commonly used grain (or ‘corn’ as this was referred to historically) for bread is wheat. A grass native to the Fertile Crescent of the Middle East, where agriculture and civilization originate, it is now cultivated across the globe, though often in marginal climatic zones. Worryingly, the last century has seen erosion of the genetic variety of wheat strains, and dependence on artificial fertilization.

From the 1940s Norman E. Borlaug and his collaborators developed new strains of wheat, correcting a structural deficiency in the stalk which couldn’t support heavy grains. Previously the most fruitful plants collapsed under the weight of their own seeds, before maturity. Borlaug’s group developed dwarf strains that could stand up to the weight of bulbous grains, thereby more than doubling yields.

Today, almost every kernel of wheat consumed by man and beast is derived from Borlaug’s selective breeding. But the resulting monocultures require greater use of pesticides than genetically diverse plants, while farmers must purchase hybrid seeds from large corporations.

Animal waste and crop rotation – traditional methods of restoring nitrogen to the soil after each growth cycle – are insufficient for the dwarf strains, which require synthetic fertilization. Wheat is now dependent on human intervention, just as modern domestic turkeys are generally unable to reproduce unless artificially inseminated.

The manufacture of synthetic fertilizer requires natural gas, both for heat and as a source of hydrogen. According to Fraser and Rimas ‘without a secure supply of nitrogen the world would starve’.[ii] Our agricultural model, and perhaps survival, is hopelessly dependent on a finite fossil fuel.

Further, it is said that stressed vines make better grapes. The same principle applies to today’s pampered wheat crop, insulated from any struggle with nature by human intervention. The diverse strains of wheat from yesteryear offered superior nutrition, and more varied flavours.

Two Methods

Notwithstanding the use of unleavened bread in Western (though not Orthodox) Christian ritual, it might be argued that such bread is not deserving of the the name, as the flour is not fermented before baking. Fermentation is achieved using one of two agents: the age-old sourdough leaven method, or through the addition of yeast.

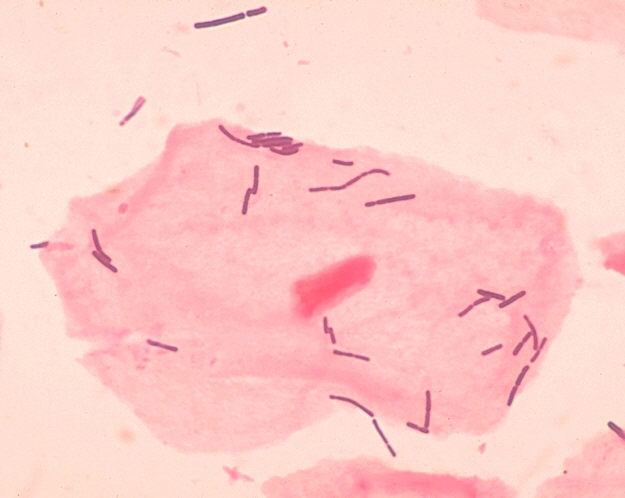

Sourdough is a combination of yeast and bacterial culture, which aids digestion of the grain. This compensates for our relatively short intestines compared to dedicated herbivores like cattle. Human ingenuity has produced what amounts to an external stomach.

Good bread, like Swiss Cheese, contains holes or ‘eyes’ left by carbon dioxide produced by fermentation and trapped by glutinous flour. This is especially apparent in strong white flours with a high gluten content; lower-protein ‘soft’ flour is usually reserved for cakes and biscuits, although it is now used in mass-produced breads.

A late-seventeenth century French journal succinctly describes the two methods of fermentation in use at the cusp of modernity:

the most commonly used one, called French leaven, is dough made with only water and flour and kept until it becomes sour… The other, which is called yeast, is the foam released from beer when it ferments. French leaven acts more slowly, causes the dough to rise less, and makes a heavier, denser bread. Yeast ferments more quickly, makes it rise more, and the bread it makes is light, delicate and soft.[iii]

These same methods are in use today, though since the breakthroughs of Louis Pasteur (1822-1895), brewers’ barm (usually derived from barley beer) has been replaced by cultured yeast with the same fast-acting effect but greater consistency.

Sourdough bread, leavened by a fermented dough ‘starter’ which has ‘caught’ yeast from the air, is denser than yeast bread. This starter contains a lactobacillus culture with sufficient yeast for bread to rise, though it is less active than pure yeast. The acetic note – its extent depending on the culture and method used – emanates from lactobacilli assisting the benign bacteria in our digestive tract.

Lactobacillus

Police Enquiry

In the seventeenth century, bread was a vital element of the diet for the average poor Parisian, who ate an impressive kilo-and-a-half per day. Indeed, the price of bread was one trigger of the French Revolution, inspiring Marie Antoinette’s famous – though apocryphal – solution: ‘let them eat cake’.

The perceived adulteration of bread with barm was, therefore, controversial. A dispute between guilds of bakers and innkeepers over the sale of bread brought the matter to a head. Innkeepers claimed that traditional sourdough Gonesse bread, purchased from out-of-town traders for retail, was superior to the yeasted ‘Queen’s bread’ sold by bakers. This bread, the innkeepers alleged, was a corruption of pure bread, i.e. dough made with only water and flour and kept until it became sour.

This early health scare led to the formation of an expert medical panel to address the issue of the use of barm, mostly imported from breweries in Flanders, sometimes in a state of autolysis. The origin of the adjective ‘barmy’ recalls the distrust, even in beer-friendly Britain, for this puzzling, fizzing substance. At that time, as today, wine was the preferred beverage in France and the inclusion of barm from beer in bread making was considered unpatriotic.

Following the debate between the guilds, a French police inquiry observed that one could take precautions against bread that was visibly poorly baked, but added: ‘It is not the same with fermentation, which makes the dough rise; which refines it and makes it lighter. Because the worst is sometimes what gives bread the best appearance of goodness.’[iv]

This echoes the sentiments of Elizabeth David centuries later in relation to the deceptive scent of baking, as she put it: ‘it is a fact of life that all bread, homemade, factory-made, bakery-made, good, indifferent, gives out a glorious smell, but to buy bread on its smell while hot is asking for disillusion.’ It seems that human senses are not always equipped to immediately discern good quality bread. Quality is revealed not just by sight, smell, or even taste, but through digestion, or rather the extent to which micro-organisms have already digested it. This accords with the oft-misrepresented Epicurus, who argued that one should avoid those foods which, though giving pleasure at the time, afterwards leave one feeling deprived.

Peasants sharing bread, from the Livre du roi Modus et de la reine Ratio, France, 14th century.

In condemning the use of yeast, the leading medical expert in the case Gui Patin stated:

To say, as those who defend it do, that they have not seen anyone drop over sick or dead from eating this bread is not a good way to clear it of the faults with which it has been charged. It is like sugar refined with lime or alum, or heavily salted, peppered and sliced meats, or wines in which one tosses lime or fish glue, or other things bad in themselves which men concerned about their health avoid, even if none of these things causes death or threatens one’s health on the day it is ingested.

In spite of this advice the Paris parliament maintained a policy of laissez faire. The preference for yeast may be explained by its faster action than leaven, and in truth many still prefer the fluffiness it imparts. Today in France pain au levain is less common than baguette de tradition française made with yeast, which is now, ironically, a symbol of France. In most countries fast-acting yeast has taken the place of the slow action of traditional leaven. Yet worse was to follow with advances in industrial technology.

Elizabeth David.

Caustic Assessment

Elizabeth David’s English Bread and Yeast Cookery, first published in 1977, provides an outstanding contribution to the subject of baking, exploring the history, science and practice of the craft. It offers a caustic assessment of the baking industry that remains as vital today as when first published, though one limitation is that most recipes call for yeast rather than sourdough leaven.

David wrote in the wake of the Chorleywood Bread Process, invented in 1961, and known in chilling Orwellian language as the ‘no-time method’. Eighty-percent of bread in the U.K. is currently prepared using this method, which involves a super-quick fermentation; the slow maturation of dough is replaced by a few minutes of intense mechanical agitation in special high-speed mixers. This sounds miraculous, but solid fat is necessary to prevent the loaf collapsing and a large quantity of yeast is added: David asserts that sixteen times as much yeast is used with the CBP as in some traditional recipes; a bit barmy really.

Such a huge amount of yeast is used in order to speed up the process, and to increase volume by maximizing dough expansion. Powdered gluten may also be added to lower-protein soft flour. Admittedly this has reduced the U.K.’s dependence on the ‘harder’ strains of wheat imported from warmer countries. Writing in the wake of the CBP, Elizabeth David remarked: ‘It will be interesting to see the efforts of the milling industry to sell us bread which is more suitable for cake, or at any rate for cattle cake.’

In fact preparing bread with soft British and Irish wheat strains is possible using artisanal methods, it just requires a longer fermentation period to develop the gluten. Perhaps as a result, over-worked bakers in the past acquired a reputation for being strong, and dumb. But the convenience of modern methods comes at a nutritional cost.

Give Us Our Bread

In the early feudal period a lord of the manor held a milling monopoly over grain grown within his domain. But by the late fourteenth century the situation had changed with the emergence of independent millers, who acquired a reputation for unscrupulous behaviour.

Robin the miller, unknown 15th century artist.

Thus, in Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales (c.1400), millers are lampooned as cheats who over-charge for grinding corn. This is an enduring stereotype revealing resentment against the wealth of an emerging capitalist class of millers, at a time when field crops formed 80% of the diets of poorer sections of society.

Our bread-dependent civilization has tended to generate and perpetuate social hierarchies dependent on the ownership of land, milling technology and the storage conditions required to preserve a year round supply, and sufficient seed for the following year.

Until recently, when health authorities recognised the importance of roughage in our diets, white or, more accurately, a yellowish-shade of bread was more expensive and reserved for the wealthy. This snobbery against darker loaves can be explained by their common adulteration with inferior grains, unground husks, and even indigestible matter.

Relative whiteness indicated purity, though the bran and wheatgerm was never entirely extracted using pre-industrial techniques. The first roller mill was opened in Glasgow in 1872 and since then white bread has been affordable for the masses, who assumed the bread esteemed by their social superiors was of a superior quality. Soon bread was even being bleached to conform to the consumer’s expectation for pristine whiteness, though most bleaching agents are now banned under E.U. (though not U.S.) law.

Oven Ready

The oven is the last piece in the jigsaw of technology and accumulated wisdom required in bread-making. Bread may be baked in a pan over an open fire in the form of ‘griddle cakes’, but a hot oven serves best, filled with steam which gelatinizes the outer layer of bread to give it a firm crust. A critical mass of population and wealth is, however, required for such ovens to be built, and the necessary fuel gathered. Thus, less technologically developed societies usually heat a cauldron over an open fire, consuming grain in the form of soup called frumenty and other stir-a-bouts.

The Second Agricultural, beginning in the seventeenth, which preceded the Industrial Revolution, led to the demise of most domestic bread-making in Britain: the Enclosure Acts denied rural communities access to common land where fuel could be gathered; it was too expensive for urban households to maintain ovens; and coal which came into widespread use billows black smoke unconducive to baking.

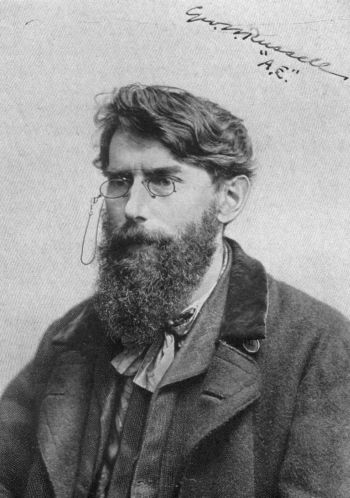

George Russell (Æ)

Over the course of the nineteenth century, shop-bought bread became the norm, especially as many women joined the labour force. In Ireland this process occurred in the latter half of the nineteenth century. In 1913 George Russell Æ observed the effect of the transition in Ireland:

There is no doubt that the vitality of the Irish people has seriously diminished, and that the change has come about with a change in the character of the food consumed. When people lived with porridge, brown bread and milk as the main ingredients in the diet, the vitality and energy of the people was noticeable, though they were much poorer than they are now… When one looks at an Irish crowd one could almost tell the diet of most of them. These anaemic girls have tea running in their veins instead of blood. These weakly looking boys have been fed on white bread.[v]

Cultural Indicator

The story of bread is like a Russian doll, a multi-layered revelation exposing a great deal of our civilization. Perhaps above any other food it requires human ingenuity in agriculture, engineering and cuisine. No wonder it provides the metaphor of transubstantiation.

Sadly, the dominance of indigestible white bread from unmatured dough has been a nutritional and gastronomic calamity. Constipation is the large and rather pained elephant clambering about the room, and bread is now marked with the dreaded sign of fat, as a contributor to the global obesity pandemic. But it shouldn’t be this way: unadulterated sourdough bread combines nutritional benefits with supreme gustatory enjoyment, in the true Epicurean sense.

One issue for us to consider is an over-reliance on hard wheat strains, considering other grains are more suited to our growing conditions. The present fluctuating climate recommends diversity, and as omnivores this is to our nutritional benefit.

The Classical Greek author Atheneaus records seventy-two varieties of bread baked in his time. Today we expect homogeneity. The spectre of food shortages looms, however, due to over-reliance on finite fossil fuels.

Individuals and communities can begin to take control of their own bread supply. Domestic baking is tricky but rewarding. In Denmark all schoolchildren are taught how to bake, a valuable lesson that could be introduced to our schools.

With more time on our hands during lockdown may have shown a willingness to make bread to a reasonable standard. Apart from saving money, this shouldn’t be too labour-intensive as sourdough keeps well without preservatives, and can be baked in batches. For most of us bread is a com-pan-ion for life, and nothing less than the best should suffice.

Feature Image: Daniele Idini

[i] Elizabeth David, English Bread and Yeast Cookery Cookbook, Grub Street, London, 2010,

[ii] Evan D. G. Fraser and Andrew Rimas, Empires of Food , and the Rise and Fall of Civilizations, Free Press, New York, 2014, p.2

[iii] Madeleine Ferrières, Sacred Cow, Mad Cow: A History of Food Fears, (translated by Jody Gladding), pp.111-133

[iv] Ibid, Ferrières

[v] Leslie Clarkson, Margaret Crawford, Feast and Famine: Food and Nutrition in Ireland 1500-1920 Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2001, p.238