Last month’s opening of the U.S. embassy in Jerusalem served to re-ignite Palestinian rage against what many there regard as a latter-day ‘Crusader’ state, a term with particular resonance in that region.

Krak des Chevaliers, Crusader Castle, Syria. Photo: Frank Armstrong, 2003.

No other city juxtaposes such piety and passion as Jerusalem. It is sacred to the three great monotheistic faiths of Judaism, Christianity and Islam, and located close to the birthplace of civilisation itself. All the dominant empires of the Mediterranean and western Asia have battled for possession of this strategic gateway to three continents, and on it goes.

With Europe enjoying a long, and increasingly complacent, holiday from its bloody history, and with the U.S. finding itself in ‘united states of amnesia’, the past is often forgotten; but in the Middle East – a heavily-laden term itself – a symbolic inheritance smoulders and crackles.

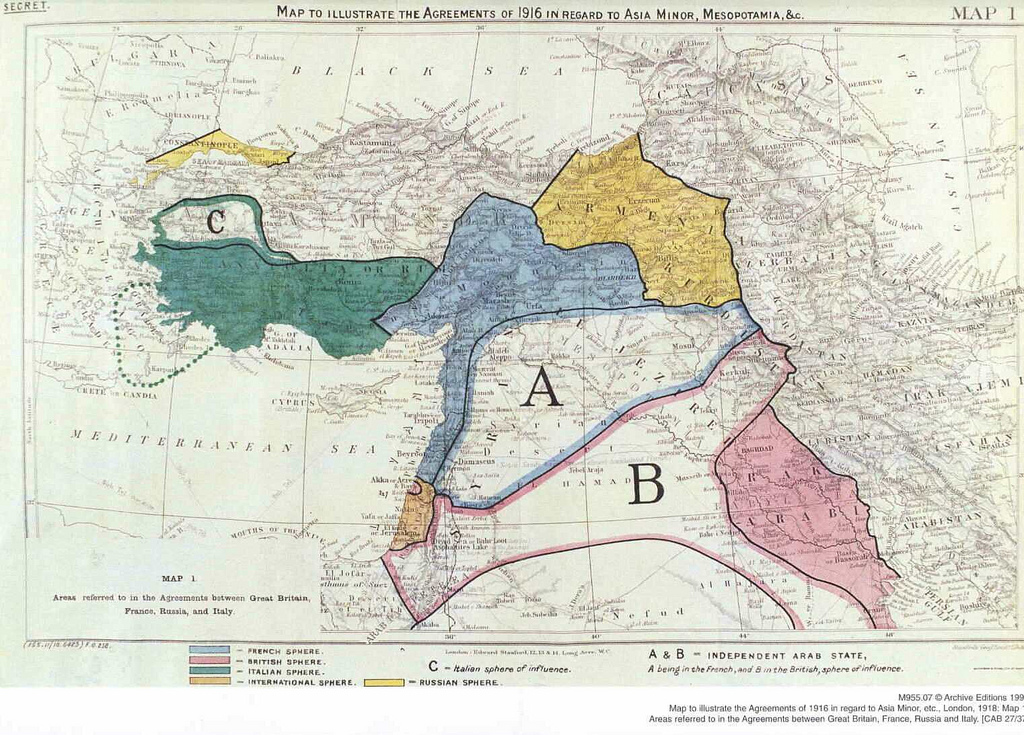

Thus, when Islamic State, or Daesh, burst into Iraqi and Syrian politics and declared a short-lived Caliphate in 2014, they claimed they were destroying the despised Sykes-Picot border. These ‘lines in the sand’ (somewhat altered after the war) demarcating post-colonial states were the product of a secret alliance between the Allied Powers to carve up the Ottoman Empire in 1916, against the claims of Arab nationalists.

The reason this latest gesture of U.S. support for the Israeli government of Benjamin Netanyahu – and nod to a domestic Christian fundamentalist audience – is a cause of such outrage lies in the profound meaning attached to the ancient city, which, ironically, derives its name from a Bronze Age ‘pagan’ deity Shalem; the preceding ‘Jeru; is a corruption of the Sumerian word ‘yeru’, for ‘settlement’ or ‘cornerstone’.

For Jews it is an historic capital, and site of the First and Second Temples, of which only the Wailing Wall survives after its destruction during the Great Jewish Revolt against Roman Rule (66-73 CE). The city also has profound associations with Christianity, as the site of the trial and crucifixion of Jesus Christ; furthermore among the Evangelical Rapture movement it is believed that the rebuilding by the Jews of their Temple will anticipate the Second Coming, which explains the devotion of many U.S. Republicans to the cause of Israel.

Islam is also deeply-embedded in the city. Many Biblical traditions contained within Judaism and Christianity were accepted by Muhammad in the Qur’an, although he explicitly denies the doctrine of the trinity (though, surprisingly, not the virgin birth) in verse 171 of the 4th Sura: Do not say, ‘Three’. Stop. It is better for you, Allah is but one God. He is far above having a son. This doctrine of tawhid or ‘oneness’ is crucial to any understanding of Islam, especially the Sunni variant.

Above all the Muslim presence in Jerusalem is located in the shimmering Dome of the Rock completed by Caliph ‘Abd al-Malik in 691 CE on the site of the Second Temple after the Islamic conquest in 638 CE.

The Dome of the Rock. Photo: Frank Armstrong, 2003.

In the The Crucible of Islam G. W. Bowersock points to a Qur’anic verse inscribed on the north door of the structure in which Muhammad condemns polytheism. This was a charge that could be leveled against Christians with the trinity in mind. Bowersock argues this did not augur well for future sectarian relations: ‘Abd al-Malik’s Dome of the Rock arose on ground that was shared by the great monotheisms, but it proclaimed only one of them and offered no path to coexistence with the other two(1)’.

This lapidary statement of intent contrasts with the relative benignity of the lightning conquest by the followers of Muhammad of a great empire stretching from the Iberian peninsula to Persia. As Bowersock puts it: ‘Archaeological evidence which has been cultivated for this period in recent years confirm the lack of any substantive impact of the Muslims on local populations.’

Adherents of other monotheistic religions in that region simply had to pay jiza – a head tax – and a tax on land known as kharaj. Despite their initial opposition, and alliance with the Sassanid Empire in Persia, Jews were far better treated under their Islamic lords than their co-religious under ‘Christian’ rulers in Europe. Those who appeal to history in the Middle East, on all sides, tend to be selective in their recollections.

II ‘Middle’ or ‘Near’ East?

The term ‘Near East’ was coined at the end of the nineteenth century to describe the Ottoman Empire and its successor states, while the expression the ‘Middle East’ was used for the area that intervened between the ‘Near’ and ‘Far’ ‘East’. With the demise of the Ottoman Empire, however, the ‘Middle East’ migrated westward and came to include the ‘Arab’ states that had emerged from the Ottoman Empire. This, in turn, heralded the emergence of ‘Central Asia’ to describe what had been the ‘Middle East’.

This has given rise to the argument, advanced in particular by Edward Said, that the term should be expunged from use. Said was reacting to an enduring European discourse used to justify imperialism, often treating the region as a special case requiring tutelage.

According to a contemporary ‘Orientalist’ Bernard Lewis (d.2018): ‘The Middle East as an area of study for scholars in the western world presents peculiar problems different from those of most other areas. It is different than a situation in which we study a part of our own society. That I think is self-evident.’

Western imperialism did not cease with the end of the British and French mandates in Iraq, Jordan, Syrian and Lebanon whose borders are the legacy of Sykes-Picot. The presence of vast oil reserves has given rise to constant meddling. David Frum, formerly a speech writer of George W. Bush, who coined the phrase ‘axis of evil’, records that Bernard Lewis was invited to the White House in November, 2001, ‘to explain his views’.

Frum approvingly noticed ‘a marked up copy of one of Bernard Lewis’s articles in the clutch of papers the president held(2).’ The extent to which archaic Orientalist opinions retain their appeal, and more importantly a propaganda value, emphasising a distinction between ‘democratic’ West, and ‘tyrannical’ East, lends credence to Said’s thesis that: ‘the vindication of Orientalism was not only its intellectual or artistic successes but its later effectiveness, its usefulness, its authority(3).’

Does the term the Middle East to describe a great swathe of territory from Morocco to Iran retain any usefulness therefore? Nikki Keddie argues the term retains an explanatory usefulness for ‘an uneasy but still adapted blend of pastoral nomadism and settled life’ in the region(4).

This has roots in the ideas of the fourteenth-century Arab historian Ibn Khaldun’s who pointed to a perpetual conflict between badu (nomadism) and hadar (urbanites) in the region. He claimed the superior ‘asabiyya (group solidarity) of the badu brought successive victories against hadar. However, after a number of generations this ‘asabiyya is corrupted by the more luxurious of life in the city, and the cycle continues(5). Even today one can see certain of these dynamics playing out in conflicts from Syria and Iraq.

Palmyra, Syria. Photo: Frank Armstrong, 2003.

Today, the term the Middle East approximates with the region subjected to the first wave of Muslim conquest (the Iberian peninsula apart), and arguably that legacy is still evident. This is not, however, to equate the region with the ‘Islamic World’, or more vaguely ‘Islamic government’, since ‘Muslims in power’ took on varying forms in places such as in India during the Mogul Empire, where it was the minority creed.

Nazih Ayubi argues that the jizya and kharaj taxes imposed by the original ‘Islamic’ state were the basis of a ‘tributary’ mode of production, involving wealth being extracted by the politically and socially superior from the politically and socially inferior. This survived into the Ottoman Empire (1299-1922), under whom all land was owned by the state, and where until the seventeenth century, armies were composed of slaves requisitioned from the populace(6).

European colonisation, especially after World War I, dragged much of the region into the world economy, sweeping away political structures in the process, but underlying cultures endured, and the architectural inheritance of the region serves as an important reminder.

Thus, the shared historical experience of much of the Middle East, under the original ‘Islamic State’ and especially the Ottoman Empire, in combination with enduring nomadic social structures suggests a regional congruence. Colonialism had a significant impact, and distorted borders, but the region is also a product of a far longer history, which encroaches heavily on the present.

III Israel’s Iron Wall

Contrary to the image of a technologically-advanced, forward-looking society, the ghosts of history also exert a magnetic pull on Israeli society.

The conduct of the Israeli authorities reflect the ideology of the Likud Party, now led by Netanyahu, which has been the dominant political force in Israel since its foundation in 1977 under Menachem Begin.

The Arab-Israeli wars which greeted the foundation of Israel in 1948 (known as al-nakba – the catastrophe – to Palestinians) brought a succession of Israeli victories, especially the 1967 Six-Day War which effectively neutralised Gamal Abdel Nasser, the erstwhile champion of Arab Nationalism.

Their ascendancy in the region was affirmed by the demise of the Soviet Union, and establishment of the U.S., Israel’s Cold War patron, as lone Superpower. The Palestinian case was further weakened by PLO support for Iraq before the first Gulf War in 1991, and the invasion of Iraq and toppling of Saddam Hussein in 2003.

But despite accords with neighbouring Egypt and Jordan, Israel faces perpetual conflict as most Arabs have a fixed view on her as a colonial, oppressive presence in the region. Only continued autocratic rule in Egypt and Jordan (maintained by vast U.S. ‘development’ aid) keeps these sentiments in check.

The Israeli electorate has consistently favoured leaders unwilling to countenance concessions, and the expansion of settlements is a fixed policy. Withdrawal from Gaza in 2006 was a strategic realisation that it was untenable to maintain 10,000 settlers inside a grossly over-populated strip of land containing over a million and a half Palestinians. Better to focus on shoring up the fertile parts of the West Bank, and Jerusalem.

To explain Israeli intransigence it is necessary to explore the basis of Likud ideology, which can be traced to three principle sources: first, the writings of Ze’ev Jabotinsky; second, the experience of the Holocaust; and third, the emergence of religious Zionism after 1967.

Zev (Vladimir) Jabotinsky.

Ze’ev (Vladimir) Jabotinsky (1880-1940), a Russian born Jew, is generally viewed as the spiritual founder of the Israeli Right. In 1923 he wrote an influential article entitled ‘On the Iron Wall (We and the Arabs)’ in which he asserted that a ‘voluntary agreement between us and the Arabs of Palestine is inconceivable now or in the foreseeable future’, since, every indigenous people ‘will resist alien settlers as long as they see any hope of ridding themselves of the dangers of foreign settlement.’

In response to resistance Jabotinsky advocated ‘an iron wall’ of military might which ‘they [the Arabs]will be powerless to break down.’ Only then ‘will they have given up all hope of getting rid of the alien settlers. Only then will extremist groups with their slogan ‘No, never’ lose their influence, and only then will their influence be transferred to more moderate groups.’ At that point he envisaged limited political rights being granted.

Jabotinsky’s metaphorical “iron wall” was given literal expression by Ariel Sharon’s construction of a ‘security fence’ in 2003 cutting through the West Bank, although the anticipated acquiescence of the Palestinians, in Hamas at least, has not materialised.

The second major influence on Likud, and Israeli society in general, is the trauma of the Holocaust experience. The collective memory of passivity in the face of genocide mandates a policy of fierce reprisal in response to the taking of Jewish life. Restraint is characterised as appeasement.

In his book A Place Among the Nations (New York, 1993) Benjamin Netanyahu dwelt on the lessons of appeasement of Nazi Germany, and the betrayal of Czechoslovakia. Arabs are likened to Nazi Germany, Palestinians to the Sudeten Germans, and Israel to the small democracy of Czechoslovakia, the victim of Neville Chamberlain’s 1938 Munich Agreement with Hitler.

This Holocaust motif was also harnessed by opponents of Yitzhak Rabin after he signed up to the Oslo Accords in 1991. Inside the Knesset (Israel’s parliament) two Likud deputies proceeded to open black umbrellas comparing Rabin’s deal to Chamberlain’s Munich capitulation, while effigies of Rabin dressed in SS uniform were set alight at right wing demonstrations.

The ferocity of Israel’s response to Hamas, however, works against the moderate leadership that Jabotinsky’s model requires. Likud policy exceeds the methodology of the ‘iron wall’, and perpetuates conflict.

The last major influence on Likud is religious Zionism, especially that generated by the optimism of the 1967 victory. Those enormous territorial gains were interpreted as a sign of divine favour, and settlement of the land became a religious imperative.

Its force was demonstrated by the assassination of Yitzhak Rabin in 1995, which effectively de-railed the Oslo Peace Process. Rabin’s killer was a young extremist by the name of Yigal Amir. During his trial Amir told the court that according to halacha (Jewish law), a Jew who gives his land to the enemy and endangers the life of other Jews must be killed.

IV The Wahhabi Formula

Alongside uncritical support of Israel, the other plank of U.S. Middle Eastern policy has been a long-standing alliance with the Al-Saud family, who gave their name to the country of Saudi Arabia in 1932. As Guardians of the Holy Cities of Mecca and Medina to which all Muslims are called on to make a pilgrimage hajj at least once in their lifetime, the hand of history lies heavily. The ruling family have used a Wahhabi blueprint to project their power both internationally and domestically

The writings of Muhammad Abdel Al-Wahhab (1703-1792), a religious scholar brought up in the strict Hanabali school, repudiate unorthodox practices such as saint veneration. This was common among the Shi’a (faction), which had broken with the dominant Sunni – faithful custodians of Muslim practice (sunna) – after the murder of the fourth caliph Ali in 661 CE.

Al-Wahhab exalted the doctrine of tawhid: ‘God’s uniqueness as omnipotent lord of creation and his uniqueness as deserving worship and the absolute devotion of his servants’, which is reflected in the inscription on the Dome of the Rock.

In 1744 Al-Wahhab entered into an accord with the tribal lord Muhammad Al-Saud. The politico-religious alliance generated vast conquests in Arabia as previously warring tribes were once again united under the banner of Islam. In exchange for ideological justification and recruits for the conquests, shari’a, religious law, as interpreted by the ulama, the religious scholars, was imposed on the territories.

In his writings Al-Wahhab emphasised that obedience to rulers is obligatory even if the ruler should be oppressive. The commands of the ruler (the imam – ‘commander of the faithful’) should only be ignored if he contradicts the rules of religion.

The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia adopted this Wahhabist formula once again at the beginning of the twentieth century, but a shift in the balance of power has seen the temporal authorities, bolstered by oil wealth, largely dictate to the ulama. This led Helen Lackner Lackner to opine that ‘the fiction of Wahhabism which has lost its real roots with the destruction of the age old desert culture can only be maintained by an intellectual petrification.(7)’

However, by the 1970s Islam had become according to Kostiner and Teitelbaum ‘a two edged political instrument – as the kingdom’s primary medium of self-legitimisation, and as the main venue of protest for opposition elements.’ Given how formal political protest, in the shape of political parties, had never been tolerated, unsurprisingly, opposition emerged from the religious milieu, culminating, arguably, in Osama bin Laden and Al-Queda.

State application of Wahhabism also leaves the Shi’a as a persecuted minority (5-10% of the overall Saudi population) perpetually at odds with the regime, and subject to repression.

Mohammed bin Salman with U.S. President Donald Trump, March, 2017.

Just as history imprisons the Israeli government in their tyrannical treatment of the Palestinians, similarly Saudi Arabia is bound by its inheritance. The current Crown Prince, thirty-two-year-old Mohammed bin Salman, courts Western approval by granting women the right to drive, but has done nothing to alter the male guardianship system, where male relatives or husbands have control over almost all aspects of women’s lives.

More meaningful is Saudi participation in the Syrian and Yemeni civil wars, which serve as bloody proxies for internal contradictions. The age-old conflict with Persia/Iran is, similarly, linked to a battle to preserve conformity in the country itself.

V Monotheism v Polytheism

No one cause explains the complex origins of conflict in the Middle East. Moreover, arguably violence is inherent in the human condition, and those of us living within the relatively peaceful confines of Europe and America are perhaps living through a golden age of relative peace. Nonetheless, it is apparent that the wars of the Middle East have boiled with almost unmatched intensity since the end of the Ottoman caliphate in 1922.

Oil wealth and vast military arsenals have played a role, as does the proximity to Europe which bequeaths embroilment in destructive alliances. But a society that had been so dominated by the instructors of a monotheistic faith now appears devoid of leadership, while the other two that emerged in the region also claim dominion. It seems in the nature of each one to suggest that the other is intolerable, despite the obvious similarities.

For centuries the Ottoman Empire imposed an orthodoxy that brought relative tranquility, but this was predicated on exploitation by social superiors. The popular appeal of Arab nationalism faded with Nasser, and failed to alter the social structures to forge genuinely fair societies. Political Islam appeared as ‘the answer’ in the late 1970s, but it has often been the only avenue for the expression of discontents, and contains within its inheritance repressive tendencies towards competing belief systems, including atheism.

Palmyra, Syria. Photo: Frank Armstrong, 2003.

In 2015 the world looked on in horror as so-called Islamic State set about destroying the remains of the Hellenic city of Palmyra, which I had the pleasure to visit in 2003. One may have assumed it was vandalism on a grand scale, but its destruction appears to have flown from the doctrine of tawhid. The disorder of the present was viewed through the prism of pre-Islamic Arabia, as Bowersock explains:

The tribes, clans and gods of Arabia at this time worked to the advantage of external powers. It was precisely this diversity and disunity that would be a threat to Muhammad when he first began to receive his revelation from Gabriel and would be resolved only as the Islamic movement gathered strength(8).

No rival could be allowed to stand before submission (Islam) to one God.

One of the pantheon of gods worshipped at Palmyra is called Allat (earlier known as Ailat). She is often depicted as a consort of another pagan god Allah, whose name Muslims appropriated for the one God of Islam. A Jungian analysis would suggest a symbolic severance from the eternal feminine, which gives rise to enduring conflict; the vehemence directed at the so-called Satanic Verses, purportedly featuring a dialogue between Muhammad and that deity, are revealing.

Jewish monotheism is not only characterised by one god but also by one people deserving of God’s intercession, which could explain the single-minded attitude of Israel towards the rest of the world. Nor has the idea of a tripartite Christian deity diluted a singular conviction legitimating the destructive colonisation of most of the planet, in the name of God. All of the monotheistic faiths are characterised by a disjunction with the feminine, and perhaps Nature itself.

Aqaba, Jordan. Photo: Frank Armstrong, 2003.

The wounds of the Middle East continue to fester, with no end in sight to the conflicts in Israel, Syria and Yemen. Religion continues to play a divisive role and forgotten are the days of the first Islamic Empire when individual conscience appears to have been respected, at least beyond Arabia. One fears that calamities will continue until a radical reappraisal of our religious traditions occur.

Frank Armstrong completed a Masters in Islamic Societies and Cultures in the School of Oriental Studies (SOAS) in 2004, and lived for a period in the Middle East.

Feature Image: Kevin Fox, all rights reserved.

(1) G. W. Bowersock The Crucible of Islam (London, 2015), p.158

(2) David Frum, The Right Man: The Surprise Presidency of George W. Bush, (New York, 2003) p.171-175

(3) Edward Said, Orientalism (New York, 1978), p.128

(4) Nikki R. Keddie, ‘Is the a Middle East’ International Journal of Middle Eastern Studies Vol. 4 (1973) p.269

(5) Nazih Ayubi, Over-stating the Arab State: State Politics and Society in the Middle East, (London 1995) p.30

(6) Ibid, p. 39

(7) Helen Lackner, A House Built on Sand – A Political Economy of Saudi Arabia, London, 1978 p.217

(8) G. W. Bowersock The Crucible of Islam (London, 2015), p.158