A new book COVID-19 and Shame: Political Emotions and Public Health in the UK (Bloomsbury, 2023) co-authored by Fred Cooper, Luna Dolezal and Arthur Rose explores how the British government under Boris Johnson used shame as an instrument of coercive control during the pandemic.

‘Shame’, the authors contend, ‘is commonly understood to be a personal experience that arises when one feels judged by another or others (whether they are present, imagined or internalized) to have transgressed or broken a social rule or norm.’

It appears to exert a particular force in Westminster politics where cries of “shame” or “shame on you” are regularly hurled across the floor of the House of Commons. An anthropologist might trace this to the public school upbringing of a significant proportion number of MPs – David Cameron recalls in his biography, ‘At bath time we had to line up naked in front of a row of Victorian metal baths and wait for the headmaster’ – or a proletarian habituation through spectator sport.

The stigmatisation of apparently errant behaviour through shaming is not, however, unique to English (or British) culture.

Over the course of the lockdown in the U.K. the authors argue that shaming became ‘an important component of the ‘collective suffering, exacerbating and complicating other negative experiences and emotions.’ Those that stepped out of line were dubbed ‘covidiots’, while people questioning canonical scientific accounts could be dismissed as a ‘conspiracy theorists’, belonging to the ‘tin-foil hat brigade’.

Arguably, a drawback of the work is a tendency to assign primary responsibility to the bumbling and often insidious response of the British government, as opposed to a wider international consensus around COVID-19 within which that government’s face-saving policies emerged.

The authors also seem reluctant to criticize a medical profession, which, they argue, were subjected to widespread shaming. Surely governments lionised ‘front line’ doctors, albeit for their own ends?

Moreover, some doctors even participated in the shaming effort, agitating for stringent measures that often were not based on cost-benefit analyses, while demonising ‘granny-killing’ objectors.

The book contains important insights into the lives of ordinary people, many of whom suffered in silence as a result of a British government strategy that often relied on ‘Second World War kitsch.’

'A state of emergency is the best friend of the would-be-dictator' Andrew Linnane wonders whether our response to Covid-19 is undermining our democracy.https://t.co/op953eTx5p@broadsheet_ie @amandaknox @IlsaCarter1 @VillageMagIRE @PaulGilgunn @AliceHarrisonBL @liamherrick

— CassandraVoices (@VoicesCassandra) November 14, 2020

Social Media

Gabor Maté describes neuromarketing as ‘a strategic invasion of human consciousness.’[i] The extent of the role of social media companies in generating fear and curbing dissent is only now being revealed. The authors draw attention to its enabling role:

Pandemic shaming was enabled by the rapid formation and spread of virtual groups on Facebook and WhatsApp, created by physical neighbours to stay in touch and help each other out during lockdown.

They recall that, ‘[a]lthough often started with the noblest of intentions, solidarity and shaming frequently inhabited the same virtual spaces.’

‘At times,’ they observe, ‘the groups became mediums for ‘curtain twitching’, or the unspoken, unofficial surveillance or monitoring of one’s neighbours.’

Thus, ‘So-called pandemic ‘transgressions’ … were documented by ordinary citizens on these platforms and elsewhere, presumably looking out for themselves and other concerned members of their community.’

It should also be noted that social media companies platformed so-called fact checkers that were responsible for disseminating misinformation that cast opposition to a dominant narrative as simultaneously absurd and sinister. A ‘Strawman Conspiracy Theorist’ was used to stifle reasonable scientific debate.

A "strawman" conspiracy theorist appears to have been developed, especially by so-called fact checkers, to deter valid journalistic enquiry during the pandemic.https://t.co/IvMv3c76Nw@broadsheet_ie @BowesChay @PD03662439 @ciarasidine @LiamDeegan3 @WhistleIRL @FutureVisions5

— CassandraVoices (@VoicesCassandra) February 12, 2022

‘Covidiots’

When historians get around to providing an account of the pandemic response – that increasingly seems like a bad dream – the cartoon villains of Johnson and Trump will surely figure prominently.

Thus, the authors observe that when the term covidiot began trending on social media in early March, ‘there seemed to be only one covidiot for Anglophone Twitter, and that was Trump.’

They say this ‘gave the earliest iterations of the term a political valency: it offered an insult that the otherwise powerless might use as a means to humiliate a powerful individual.’

They argue:

[this] relied upon a historical tendency to portray Trump as morally and intellectually deficient throughout his candidacy for, and eventual elevation to, the US presidency. Seen in this light, the neologism owed its first success to the ease with which it fitted into an existing paradigm, as a novel shorthand for describing an existing situation.

Whatever came out of Trump’s mouth was consigned to covidiocy, even if he, occasionally, made sensible suggestions such as that the cure should not be worse than the disease. Profound antipathy towards Trump seems to have been exploited by lockdown evangelists, which caused profound damage, especially in developing countries such as India.

The book provides harrowing accounts of ordinary people caught in the crossfire of what became a culture war. The authors point to poignant accounts of the effect on society from the Mass Observation project:

I went out on Tuesday, with my son, to buy stamps. I sensed a slight hostility. People who would usually smile and let you through a door now avoid eye contact and stay their distance. The woman working in the Post Office was expressing her anger at people who had congregated on the beach the previous day. She hadn’t seen it herself, she said; but it was on Facebook (it must be true!) She said they were idiotic. It differed from her usual affable small-talk and it made me un-easy. I said we had been ourselves on Sunday and there was no-one around.

Frank Armstrong argues we shouldn't rule out vaccines causing 'among the worst' excess death figures in 50 years, but identifies a more likely reason for this.https://t.co/fUBQG1EzIJ#ExcessMortality #CovidIsNotOver #CovidVaccine

— CassandraVoices (@VoicesCassandra) February 22, 2023

Irish Experience

In Ireland we witnessed similar shaming tactics. Thus, in the so-called ‘paper of record’ the Irish Times, a column from Dr Padraig Moran from November, 2020, arrived with the by-line: ‘Mindless rule-flouting behaviour is the real problem in the pandemic.’ Another article by Kathy Sheridan from 2020 referred to ‘maskless ignoramuses with Trumpian belief systems.’

A grandmother was even jailed in Ireland for refusing to wear a mask in shops and restaurants.

Unsurprisingly, we have seen no retractions or reassessments on the subject of those “maskless ignoramuses”, despite a Cochrane review stating that the ‘pooled results of RCTs did not show a clear reduction in respiratory viral infection with the use of medical/surgical masks.’

The shaming reached a crescendo in Ireland with vaccine passes and the scapegoating of an unvaccinated minority by politicians and prominent journalists in late 2021.

Gabor Maté provides a fitting description of the political class that exploited the virus for their own ends:

The system works with cyclic elegance: a culture founded on mistaken beliefs regarding who and what we are creates conditions that frustrate basic needs, breeding a populace in pain, disconnected from itself, others and meaning. A select few – especially those with the sort of coping mechanisms that prime the to deny reality, block out empathy, fear and vulnerability, mute their own sense of right and wrong, and abjure looking at themselves too closely – will be elevated to power.[ii]

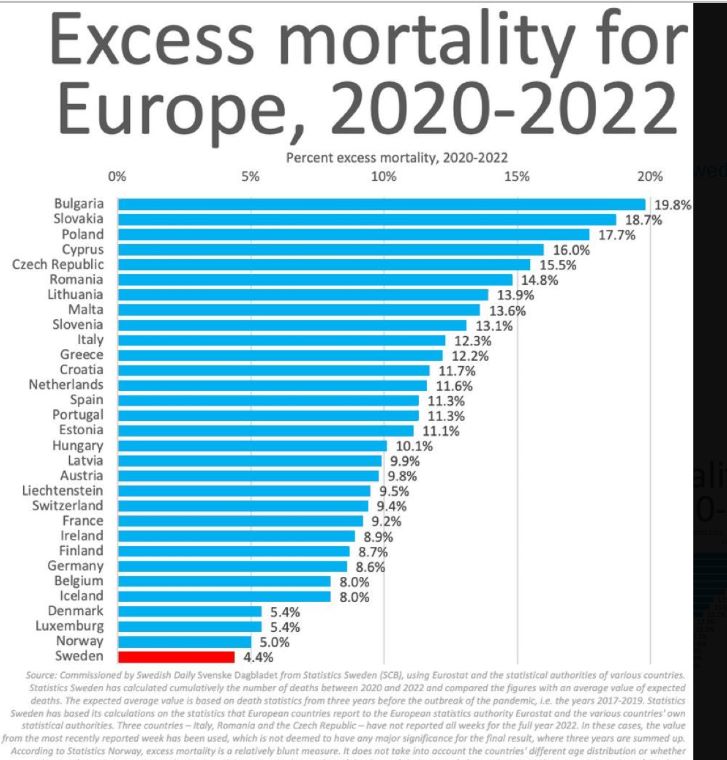

Sadly, many among the medical profession were fully on board with this effort, disregarding the traumas caused by lockdowns, which seems to be contributing to the excess deaths we are witnessing in the wake of the pandemic. The fact that Sweden has experienced the lowest level of excess death in Europe over the period is widely ignored by those that condemned that country as a pariah state.

This is perhaps unsurprisingly given Gabor Maté’s observation that, ‘[a]t present there remains powerful resistance to trauma awareness on the part of the medical profession’[iii]

Given so much of what we saw during the pandemic in the U.K. and beyond was guided by the medical profession it seems, as Jon Jureidini and Leemon B. McHenry put it ‘a complete revolution in medicine is exactly what is required.’[iv]

Richard Kearney's Touch asserts the importance of physical contant in healing. Crippling anxiety in the wake of COVID-19 indicates a need for medicine to reform.https://t.co/4SLoA3YFaK@broadsheet_ie @BowesChay @indepdubnrth @corourke91 @itsmybike @NMcDevitt @iHealthReform

— CassandraVoices (@VoicesCassandra) December 1, 2021

[i] Gabor Maté, The Myth of Normal: Trauma, Illness, & Healing in a Toxic Culture, New York, 2022, p.299

[ii] Ibid, p.357

[iii] Ibid, p.277

[iv] Jon Jureidini and Leemon B. McHenry, The Illusion of Evidence-Based Medicine: Exposing the crisis of credibility in clinical research, Wakefield Press, South Australia, 2020, p.198.

Feature Image: Village stocks in Bramhall, England, c. 1900.