Architects … are better able than many other professions to ride out recessions … They will use the lean times to think hard about the directions architecture might take when the good times roll once again.

(Glancey, 2009)

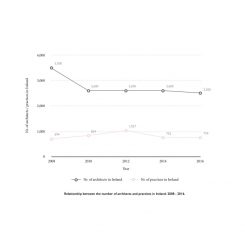

In August 2008 Ireland was the first EU country to declare itself officially in recession. The economic downturn was swift, and in the succeeding years the country found itself in the grip of a sustained economic depression, occasioned by the convergent demise of the banking and construction sectors.

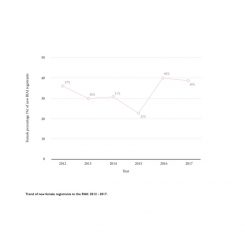

The collapse of the construction industry ‘hit the architect profession at a faster rate than other professions’[1] with almost one third of architectural firms laying off between 61% and 100% of their staff.[2] The constriction of the profession was seismic, disproportionately affecting marginalized and vulnerable constituents of the workforce; notably female architects.

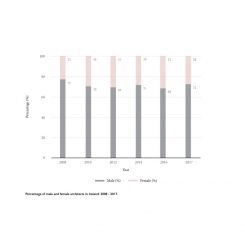

Despite almost gender parity in architectural education, women compose just 28% of registered architects in Ireland.[3] Burdened by unsuitable working practices, lower pay and a general deficiency in numbers, the practice of architecture can be an unforgiving topography for many women. While this predicament may seem embedded within the industry, it is clear that ‘the harsh economic climate has … undercut the conditions which are conducive to gender equality,’[4] leading to the enduring phenomenon of highly skilled female architects disappearing from the profession.

There has been a paucity of research in recent years on the relationship between the struggles women face and the economic factors that contribute towards them, and it is within this context that a debate on redefining the profession and production of architecture for female (and male) architects is required. Using the recession as a catalyst for change, it is essential that architects ‘recognise the importance of continuing to challenge the labour market disadvantage that women…face,’[5] by acknowledging the factors that unduly affect them, principally: the outdated, gendered image of the architect; a pervasive long-hours working culture that disproportionately affects those caring for dependents; the profession’s intolerance toward flexible working; and the general deficiency of senior positions available to women within mainstream practice.

In this study alternative forms of working – such as flexible, part-time working and the creation of more female-led practices to inspire the next generation of architects – will be explored as a means of fostering a more inclusive and equitable profession for all.

The scope of this study is consciously narrow, its aim is to ignite a wider discussion on the vital contributions women make within the industry, and the efforts that must be taken to prevent the continuing trend of women leaving it.

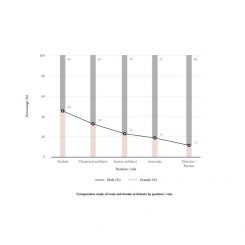

In recent decades the number of female students entering architectural education has risen steadily year-on-year, with female enrollment now on a par with that of male students.[6] Despite this encouraging trajectory, women’s participation stagnates as they progress through the profession with the ‘percentage of women (falling) at each ascending management tier.’[7]

In 2006, research conducted for the Architect Journal’s ‘Women in Architecture’ campaign highlighted the attrition of female architects from the profession, noting that while 35% of undergraduate students were female, women accounted for only 4% of retiring architects.[8] The spectre of this missing 31% is damaging to the future of the profession and it is therefore essential to call attention to the structural issues that motivate it.

1.1 The image of the (female) architect

(a woman’s) intellect is not for invention or creation, but for sweet ordering, arrangement, and decision.

John Ruskin

That Ruskin’s indelicate stance on the capacity and worth of creative women so closely typifies prevailing contemporary attitudes towards female architects is not surprising. Indeed, clichés abound about women in architecture today, ’many of which are destructive and detrimental…entrenched assumptions about what it is to be an architect.’[9]

These ‘entrenched assumptions’ appear to be borne out of engendered prejudices of what an architect is and what they do. Certainly throughout history architects have been many things – artists; philosophers; master-builders – but only recently have some been women. Women’s involvement in – as Ruskin would characterise – ‘invention or creation’ has therefore been largely overwhelmed and diminished by the vast contribution that male architects have made before them.

This, coupled with the architectural establishment’s casual misogyny in the erasure of pioneering female architects’ achievements, has done little to recast the image of the architect as anything other than male. Most notably, the awarding of the 1991 Pritzker Prize to Robert Venturi, but not his wife and practice co-founder Denise Scott Brown, led a chorus of voices to question why Scott Brown’s equal contribution and authorship were not similarly honoured. Furthermore, the removal of Patty Hopkins – co-founder of Hopkins Architects – from promotional material for the BBC’s ‘The Brits Who Built the Modern World’ series does little to foster the idea that architecture is anything other than a male domain.‘’

This airbrushing of the contributions women have made to the profession has rendered them invisible, allowing enduring prejudices of what an architect should be to persist and encouraging female architects to feel that their efforts are not worthy of the same recognition as their male counterparts.

1.2 Children

While there are various factors that contribute towards the attrition of female architects at different stages in their career, maternity appears to be a principal factor.

Having children impacts the careers of women considerably more than men,[10] and a recent survey conducted by the Architects Journal found that 92% of female architects believed that having children had hindered their career prospects.[11] Women have commented that after having children they were ‘not taken seriously, were sometimes demoted, passed over for promotion or were seen to have failed to give the art of architecture the full attention it deserved.’[12]

As soon as I started working part-time my employers treated me differently and assumed I was less committed. I was overlooked for promotion twice when I was on maternity leave and not even informed that structural changes were being considered.[13]

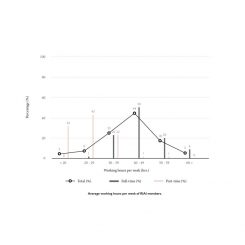

1.3 Long hours: time-discipline in architecture

‘An important factor in the flow of women from the architecture profession is the family-hostile, long hours working culture that still prevails’[14] within mainstream practice.

Long-hours have become an accepted and pervasive element of being a salaried architect, indiscriminately affecting both men and women in the pursuit of making a project the best it can be. Evening meetings, project deadline, and the over-servicing of projects beyond the negotiated fee, can prolong the working day, significantly encroaching on an architect’s personal time. ‘’Theoretically ‘work devotion’ is gender neutral, but the long working day … relies on a social foundation of gender norms that disadvantages women’[15] more than their male colleagues.

Consequently, flexible working is often favoured by women ‘as a strategy to reconcile the competing time demands of paid work and family life.’[16]

Unsurprisingly, architecture is often considered to be more intolerant of part-time work than other professions, with one of the strongest barriers to flexible employment being the established long-hours culture within the profession.[17] Periods of economic and employment uncertainty encourage this culture of working by creating ‘a climate where it is necessary to demonstrate high commitment’[18] and ‘unfailing availability’[19] to the job. This has led to what Karen Burns, in her chapter for the recent RIBA publication, ‘A Gendered Profession: The Question of Representation in Space Making,’ describes as ‘‘competitive overstaying’, as employees contend with each other to demonstrate loyalty and devotion to work,’[20] in an effort to stymie possible redundancy.

Consequently, many women forced into redundancy following the 2008 recession have commented that their inability to pursue long-hours working meant they were considered easy targets due to a ‘two-tier system where part-time and flexible workers are seen as less legitimate or committed workers.’[21] In this context, women are unfairly disadvantaged by having responsibilities outside of the workplace, which are incompatible with working beyond contractually agreed hours with no or little remuneration.

1.4 Career advancement

In recent years Parlour – the Australian gender advocacy group – has challenged the long-hours system in architecture arguing that the ‘culture…retards the retention of female architects, and hinders women’s progression to senior levels.’[22]

The growing chasm between men and women as they advance up the architectural ladder has been highlighted in research conducted by the Architectural Association, which notes that only 20% of partners in architectural practice are women, this figure dropping to just 5% in large practices.[23]

While it is clear that women possess the same motivation and skill to succeed in senior roles, employers remain largely unsympathetic towards family life, perceiving full-time work as the only means of servicing projects, and conveying dedication to the often unrelenting and demanding expectations of the highest echelons of the profession.[24]

Indeed, part-time working is a key factor in women’s under-representation in senior architectural positions as ‘women are more likely to have ‘atypical’ or flexible career paths, with multiple breaks, different levels of intensity and changing roles over the course of a career.’[25] In contrast, men are more likely to follow a ‘traditional’ career model – that of unbroken and unwavering devotion to the profession via unpaid overtime – and be ‘active in the conventional areas of influence and power in the profession. (It is clear) the structures of the profession are still geared towards (the) linear, rising career trajectories,’[26] favoured by men.

As women are often unable to meet the loyalty and dedication that many employers expect, senior roles often appear unattainable for the majority of women. With little hope of career advancement in a profession that openly favours a ‘traditional’ working model, it is unsurprising that a significant number of women choose to leave the profession.

It is clear that within the architectural profession a system persists that works against the specific needs of women. It is essential, therefore, that the contributory factors to this system are no longer viewed merely as accepted inconveniences, but rather as opportunities to reduce the current rate of attrition. Indeed, ‘women architects’ commonly interrupted career history, and need for flexible working conditions can be reframed not as an aberrant or problematic work pattern, but as the model for innovative new professional paradigms in architecture.”[27]

2.1 The case for meaningful flexible working

If the practice of long-hours is ‘read as a signal of productivity and commitment, flexibility can be perceived as a conflict with an organisation or profession’s norms.’[28] A recent survey conducted by the RIAI has reinforced the low levels of support for part-time work in architecture, identifying 10% of architects as working part-time compared with 38% for all professions. ‘This is a particular problem for women (as) 27% of all women professionals work part-time, while only 16% of women in architecture do.’[29]

The stigma surrounding flexible working has stymied the adoption of part-time and non-standard working methods for decades, encouraging entrenched negative perceptions of alternative working models to fester.

Changing these attitudes is crucial if more meaningful part-time arrangements are to be developed.[30]

Positively, flexible working policies are inherently responsive, allowing both employers and employees to react to specific needs at particular times.[31] For employees meaningful part-time work can provide a balance between external demands and the rigours of professional practice, while for employers it allows quick responses to ever-changing workloads. Practices can explore the potential of flexible working simply by cultivating job-sharing arrangements; coupling part-time and full-time members of staff on projects; and providing staff access to new technology to facilitate home working. Many practices report that implementing these measures has ‘reduced amounts of overtime required while increasing productivity and maintaining the quality of their work.’[32]

It is important that practices make a virtue of these working arrangements as ‘a forward-looking, equitable … firm is attractive to clients and new staff.’[33] Furthermore, in the context of the recent recession ‘introducing flexible working options … in workplaces where there is a history of reducing hours or changing patterns of work in response to demand, could prove a valuable means to retain jobs … and (provide) greater flexibility for workers now and as the economy recovers.”[34]

2.2 New (role) models of practice

As non-traditional, flexible forms of working have increased in recent years, the notion of what constitutes a ‘career’ in architecture has been queried.

The recent influx of equitable practices such as Assemble, Fluid and earlier pioneers such as Muf have consciously positioned their work on the fringes of the profession,[35] putting greater emphasis on social rather than financial rewards. Entrepreneurial in nature, these practices have boycotted the traditional forms of working in favour of ‘non-standard’, inventive modes of practice that have proven to be more innovative and diverse in form.

Research suggests that the last recession encouraged the adoption of more ‘non-standard’ working as architects sought to find relevance within an industry decimated by construction inactivity. Consequently, the success of practices such as Assemble must motivate architects to embrace new, more loosely architectural ways of working as a means of adapting more easily to ever-changing economic and work/life balance conditions.

2.3 A Practice of One’s Own

The embrace of new working models in recent years has largely been borne out of necessity. For those made redundant and unable to find work following the 2008 recession “a trend, common to all recessions in the construction industry, for the unwaged or unemployed to form new architectural practices, reoccurred.”[36]

This trend follows an increasing pattern of women who ‘end up in small practice, or starting their own practice, not because they actively choose to…but because they find themselves with few other options.’[37] Indeed, according to a recent survey published by the Architects Journal, 16% of female architects become self-employed after having children due to the complexities of carving a rewarding career in mainstream practice whilst caring for dependents.

One of my main reasons for working as a sole practitioner was for the flexibility. I have small children, and running my own practice has allowed me to juggle motherhood and my work. [38]

That female sole-practitioners report ‘remarkably high levels of job satisfaction’[39] should, however, encourage us to reconsider self-employment not merely as a necessary response when times are hard but an effective means of reclaiming personal autonomy and organising levels of project engagement around external demands. Moreover, for many young female architects, who cite a lack of female-run practices ‘as a factor leading to (the) under-representation of women in architecture,’[40] seeing more women subvert the established routes of career ascension and actively counter the pervasive negative stereotypes that cast doubt on their ability to perform in the profession will ‘increase (their) motivation for career advancement and success.’[41] The effects of encouraging more female role models within an overtly male-dominated profession like architecture should not be underestimated.

Conclusion

Recessions are a time for architects to rethink their game. They need not despair – but, rather, regroup for the next boom.

Glancey (2009)

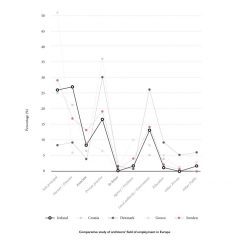

Prior to the 2008 economic crisis Ireland possessed one of the highest levels of workplace gender parity in Europe.[42] This changed however as an entire framework of statutory and public bodies promoting equality endured drastic budget cuts and closures.[43] The seismic withdrawal of gender policy in the aftermath of the recession is indicative of the large-scale marginalisation of issues that affect women in the workforce, specifically in architecture.

For a profession that claims to be concerned by societal inequalities, the recession highlighted ‘a major discrepancy … between the egalitarian rhetoric of architecture and its backstage realities.’[44] Indeed, the recession exposed a myriad of pervasive and deeply rooted inequalities within the profession that disproportionately impact women, and have contributed significantly to their decision to leave the profession over recent decades.

Central to the inequalities experienced by women is the long-hours culture that permeates all aspects of mainstream practice. The persistent misconception that those who are unable to commit to long-hours are less committed to the profession has become a significant impediment to women who predominately undertake the majority of dependent responsibilities. This, coupled with the view that those with children are unable to undertake managerial positions, has ensured women’s career advancement has stagnated with a minority of women currently occupying director or partner positions. Consequently, the under-representation of women in leadership roles has ensured the dominant image of the architect is still male, effectively rendering women’s significant accomplishments in recent decades obsolete.

As frustrating as this pattern may seem it is within our power to change it. Encouragingly, Ireland has a wealth of extraordinary and internationally-renowned talent, with female-led and co-led practices such as Grafton Architects, Heneghan Peng and O’Donnell and Tuomey proving that women can create meaningful change if they challenge the structures that work against them. The growth of more female-led practices could help slow the current attrition rate of women from the profession as more women ‘put themselves forward and become visible and influential.’[45] Furthermore, by implementing new strategies, such as flexible working, that ‘mediate between the day-to-day activity of producing architecture and each woman’s individual needs’[46] both employers and employees can respond better to work/life demands.

The propositions put forth in this study are consciously simple solutions to the larger problem of inequality within the profession. While the case for more appropriate and flexible working practices is unlikely to constitute a sustained assault on the profession-at-large, it may, at least, encourage an incremental erosion of the problems that have been allowed to fester for too long.

In short, it is clear the profession needs to retain ‘more people who think (and work) in diverse ways, not fewer’[47] if it is to deliver better working environments for all architects – not just women – and if it is to survive the next, inevitable recession.

Did you know that Cassandra Voices has just published a print annual containing our best articles, stories, poems and photography from 2018? It’s a big book! To find out where you can purchase it, or order it, email [email protected]

[1] Prescott, J. and Bogg, J., Gendered occupational differences in science, engineering, and technology careers. Hershey, PA: Information Science Reference, pp.49-52., 2013, p.49

[2] Hays.ie. (n.d.). Architectural firms have shed an average of 60% of employees in two years. [online]Available at: https://www.hays.ie/press-releases/HAYS_163705 [Accessed 25 Nov. 2018].

[3] RIAI Membership Survey 2017. [online]The Royal Institute of the Architects of Ireland. Available at: https://www.riai.ie/uploads/files/RIAI-Membership-Survey.pdf [Accessed 5 Nov. 2018], p.2

[4] Fowler, B. and Wilson, F., Women Architects and Their Discontents. Sociology, 38(1), pp.101-119. , 2004, p.117

[5] TUC (2009). Women and Recession: How will this recession affect women at work?. [ebook]Available at: https://www.ictu.ie/download/pdf/womenandrecession.pdf [Accessed 27 Oct. 2018], p.8

[6] Clark, J., Six myths about women in architecturre. In: J. Benedict Brown, H. Harriss, R. Morrow and J. Soane, ed., A Gendered Profession: The question of representation in space making. London: RIBA Publishing, 2016, p.18

[7] Fairs, M. (2017). Female architects respond to gender survey: “It’s getting better but far too slowly”. [online]Dezeen. Available at: https://www.dezeen.com/2017/11/17/female-architects-respond-architecture-gender-survey-worlds-biggest-firms/ [Accessed 27 Oct. 2018]., 2017

[8] Duncan, J. and Newman, V., Women in architecture: stand up and be counted. In: J. Benedict Brown, H. Harriss, R. Morrow and J. Soane, ed., A Gendered Profession: The question of representation in space making. London: RIBA Publishing. 2016, p.61

[9] Clark, 2016, p.15

[10] Stead, N., Redesigning practice. [online]Parlour. Available at: http://archiparlour.org/setting-our-own-house-in-order/ [Accessed 17 Oct. 2018], 2012.

[11] Brown, et al., 2016, p.7

[12] Manley, S. and de-Graft-Johnson, A., Why women still leave architecture? A research report. Women & Environment International Magazine, [online]62(63), pp.19-20. Available at: https://search-proquest-com.ucd.idm.oclc.org/docview/211604807?accountid=14507&pq-origsite=summon [Accessed 5 Nov. 2018]., 2004, p.20

[13] Burns, K., The Hero’s Journey: Architecture’s ‘long hours’ culture. In: J. Benedict Brown, H. Harriss, R. Morrow and J. Soane, ed., A Gendered Profession: The question of representation in space making. London: RIBA Publishing., 2016, p.66

[14] Humphryes, J., Redesigning the profession. In: J. Benedict Brown, H. Harriss, R. Morrow and J. Soane, ed., A Gendered Profession: The question of representation in space making. London: RIBA Publishing., 2016, p.121

[15] Burns, 2016, p.66

[16] Rose, J., Hewitt, B. and Baxter, J. (2011). Women and part-time employment. Journal of Sociology, 49(1), pp.41-59, p.41

[17] The Parlour Guides to Equitable Practice: Long-hours culture. (2014). [ebook]University of Melbourne and University of Queensland. Available at: http://www.archiparlour.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/Guide2-LongHours.pdf [Accessed 27 Oct. 2018], p.9

[18] Craven, V. (2004). Constructing a career: women architects at work. Career Development International, [online]9(4/5), pp.518-531. Available at: https://search-proquest-com.ucd.idm.oclc.org/docview/219290042/fulltextPDF/358285285D7E4C03PQ/1?accountid=14507 [Accessed 5 Nov. 2018]. p.524

[19] Mark, L., Women in architecture survey 2017: Pay gap widens between male and female architects. Architects Journal, 244(3), pp.1-30., 2017, p.30

[20] Burns, 2016, p.64

[21] Parlour, n.d., p.3

[22] Burns, 2016, p.64

[23] Humphryes, 2016, p.120

[24] Clark, 2016, p.25

[25] Clark, 2016, p.27

[26] Clark, 2016, p.27

[27] Stead, 2012

[28] Burns, 2016, p.66

[29] Clark, 2016, p.26

[30] Parlour, n.d., p.4

[31] Parlour, n.d., p.4

[32] Parlour, n.d., p.4

[33] Rubery, J. and Rafferty, A. (2013). Women and recession revisited. Work, Employment and Society, 27(3), pp.414-432., n.d., p.426

[34] TUC, n.d., p.9

[35] Hamer, S., On age and architecture. In: J. Benedict Brown, H. Harriss, R. Morrow and J. Soane, ed., A Gendered Profession: The question of representation in space making. London: RIBA Publishing., 2016 p.45

[36] RIAI Annual Report 2007. [online]The Royal Institute of the Architects of Ireland. Available at: https://www.riai.ie/downloads/annual_reports/2007_Annual_Report.pdf [Accessed 27 Oct. 2018].The Royal Institute of the Architects of Ireland, 2007, p.16

[37] Clark, 2016, p.22

[38] Clark, 2016, p.22

[39] Stead, 2012

[40] Humphryes, 2016, p.119

[41] Stratigakos, D. (2016). Where are the women architects?. Princeton: Princeton University Press., 2016, p.35

[42] Barry, U. and Conroy, P. Ireland in crisis 2008-2012: women, austerity and inequality. [ebook], 2013, Routledge. Available at: https://researchrepository.ucd.ie/handle/10197/4820 [Accessed 27 Oct. 2018]., 2012, p.1

[43] Ibid, 2012, p.29

[44] Fowler, B. and Wilson, F., 2004, p.114

[45] Duncan and Newman, 2016, p.59

[46] Pepchinski, M., And then we were the 99%: Reflections on gender and the changing contours of German architectural practice. In: J. Benedict Brown, H. Harriss, R. Morrow and J. Soane, ed., A Gendered Profession: The question of representation in space making. London: RIBA Publishing, 2016, p.245

[47] Clark, 2016, p.29