Not since Byron awoke one morning to find himself famous has there been such an example of world-wide celebrity won in a day by a book as has come to Upton Sinclair.

The New York Evening World, 1906.

Perhaps others, better acquainted with the genre, may argue to the contrary, but Upton Sinclair’s 1906 novel The Jungle is surely a contender as the Great American Novel. Though far from an ideological bedfellow, Winston Churchill nonetheless wrote admiringly that Sinclair had marshalled his forces like the general of an army on the attack.[i]

That the work is not better known today is probably on account of the butcher’s blade it takes to the American Dream, and the presentation of an alternative vision for humanity. Thus, Socialism is described as ‘the new religion of humanity – or you might say it was the fulfilment of the old religion, since it implied but the literal application of all the teachings of Christ (p.346)’.

The Jungle is generally credited with the swift passage of the Pure Food and Drug Act in June 1906 – eventually leading to the creation of the FDA – after laying bare to the American public the unsanitary practices of the Beef Trust in Chicago’s Packingtown.

Notably, however, action was only taken when the health of the US population at large seemed at stake. Sinclair claimed the “embalmed beef” scandal ‘killed several times as many soldiers as all the bullets of the Spaniards(p.105)’ in the war of 1898.

The Act did not, however, address the frightful working conditions of mainly immigrant workers in the meat packing industry; let alone the millions of animals subjected to industrial slaughter. Moreover, in certain respects, the industrial food system is now more disturbing than ever, while the FDA has long been subject to Regulatory Capture.

At least we have The Jungle to remind us of ongoing fraudulent misrepresentations:

The storekeepers plastered up their windows with all sorts of lies to entice you; the very fences of the wayside, the lamp-posts and telegraph-poles, were pasted with lies. The great corporation which employed you lied to you, and lied to the whole country – from top to bottom it was nothing but one gigantic lie(p.82).

A Time of Hope

The opening chapter introduces an unlikely hero, Jurgis Rudkus – ‘he with the mighty shoulders and the giant hands (p.4)’ who is ‘the sort of man the bosses like to get hold of(p.23)’ – a recent Lithuanian immigrant to ‘Packingtown’, Chicago, along with an extended family group, who are being ground down by unrelenting work and squalid conditions.

In spite of abject poverty the family nonetheless insists on a proper occasion for Jurgis’s wedding to his beloved Ona: ‘these poor people have given up everything else; but to this they cling with all the power of their souls – they cannot give up the veselija(p.15).’

At that point, still imbued with optimism, Jurgis’s response to any of the multiple challenges he confronts is to shrug his broad shoulders and say he will just have to work harder. It makes him an early model for Boxer in George Orwell’s Animal Farm. His love for Ona – recalling in certain respects Odysseus’s journey towards Penelope – means he resists the lure of the saloons, which most workers frequent.

But in a pedagogic aside – after the family are confronted with a higher than expected bill for the wedding – Sinclair intimates that the brutal nature of the work in Packingtown erodes moral as well as physical beings: ‘for men who have to crack the heads of an animal all day seem to get into the habit, and to practice it on their friends, and even on their families.(p.20)’

At the time about ten thousand head of cattle and as many hogs and half as many sheep were disposed of every day, amounting to eight to ten million live creatures turned into food every year.

It was ‘the greatest aggregation of labor and capital ever gathered in one place’, employing thirty thousand men, supporting directly two hundred and fifty thousand people in it neighbourhood, and indirectly half million, and ‘furnished the food for no less than thirty million people(p.45)’ – or at least whatever could be passed off as such.

Neil Burns rates James Plunkett's 1969 novel Strumpet City depicting the 1913 Lockout as a masterpiece that explores the scene in the manner of a Russian novel.https://t.co/Zwc3hl1Zgy@broadsheet_ie @BowesChay @IlsaCarter1 @foreverantrim @danieleidiniph1 @wadeinthewate11

— CassandraVoices (@VoicesCassandra) August 15, 2021

Speeding up the Gang

In what is a distressing account, the reader is introduced to a succession of despicable practices that drain away human life by degrees, while imperilling consumer health. One such is “speeding up the gang”, where a foremen alternates picked men to set up a hectic pace ‘and if any man could not keep up with the pace, there were hundreds outside begging to try(p.63)’.

As he works, Jurgis finds numerous examples of shoddy corruption. Thus, a good many so-called “slunk” calves turned up every day:

Any man who knows anything about butchering knows that the flesh of a cow that is about to calve, or has just calved, is not fit for food … if they had chosen, it would have been an easy matter for the packers to keep them till they were fit for food.

This inconvenience would lead to a loss of revenue however, thus:

whoever noticed it would tell the boss, and the boss would start up a conversation with the government inspector, and the two would stroll away. So in a trice the carcass of the cow would be cleaned out(p.68).

There were also “Downers”: cattle that are injured or die on the long journey to slaughter. These too are surreptitiously placed alongside healthier specimens.

Shockingly, the meat of tubercular cattle is also permitted to enter the food chain, in return for ‘two thousand dollars a week hush money.(p.104)’ It is hardly surprising, therefore, that the book triggered a political scandal.

Property Swindle

On arrival in Chicago the family find a dilapidated boarding house to reside, but strive to purchase a property in fulfilment of their American Dream – assuming this will be a saving in the long run for a working family.

Jurgis chances on an advertisement featuring a brilliantly painted house, under which there is a picture of a husband and wife in warm embrace. Underneath is written – helpfully in Lithuanian – “Why pay rent?” “Why not out own your own home.(p.51)”

When they view the house, however, it is not ‘as it was shown in the pictures(p.52)’ –albeit it has been freshly painted. Despite the agent’s exhortations that the sale must be closed without delay, or they risk losing the opportunity, they follow their gut instinct and hold off from purchasing. They are eventually duped into signing on the dotted line by a dodgy lawyer who assures them it is a perfectly regular deed.

So, they part with their savings, leaving them on the hook for a monthly repayment that stretches them to the limits of endurance.

As if this isn’t hard enough – especially in return for what they soon discover is a house that is barely fit for human habitation – a few months later they are presented with an annual insurance bill that threatens to starve them into submission.

Predictably, after Jurgis gets into trouble with the law and cannot work, the family loses the home – and their hard-earned savings – and are forced to return to the boarding house from whence they came, where further trials await.

Ironically, a century later millions of Americans, and others, had a similar experience of losing their homes, and savings, in the Financial Crash, in large part due to banks offering easy credit.

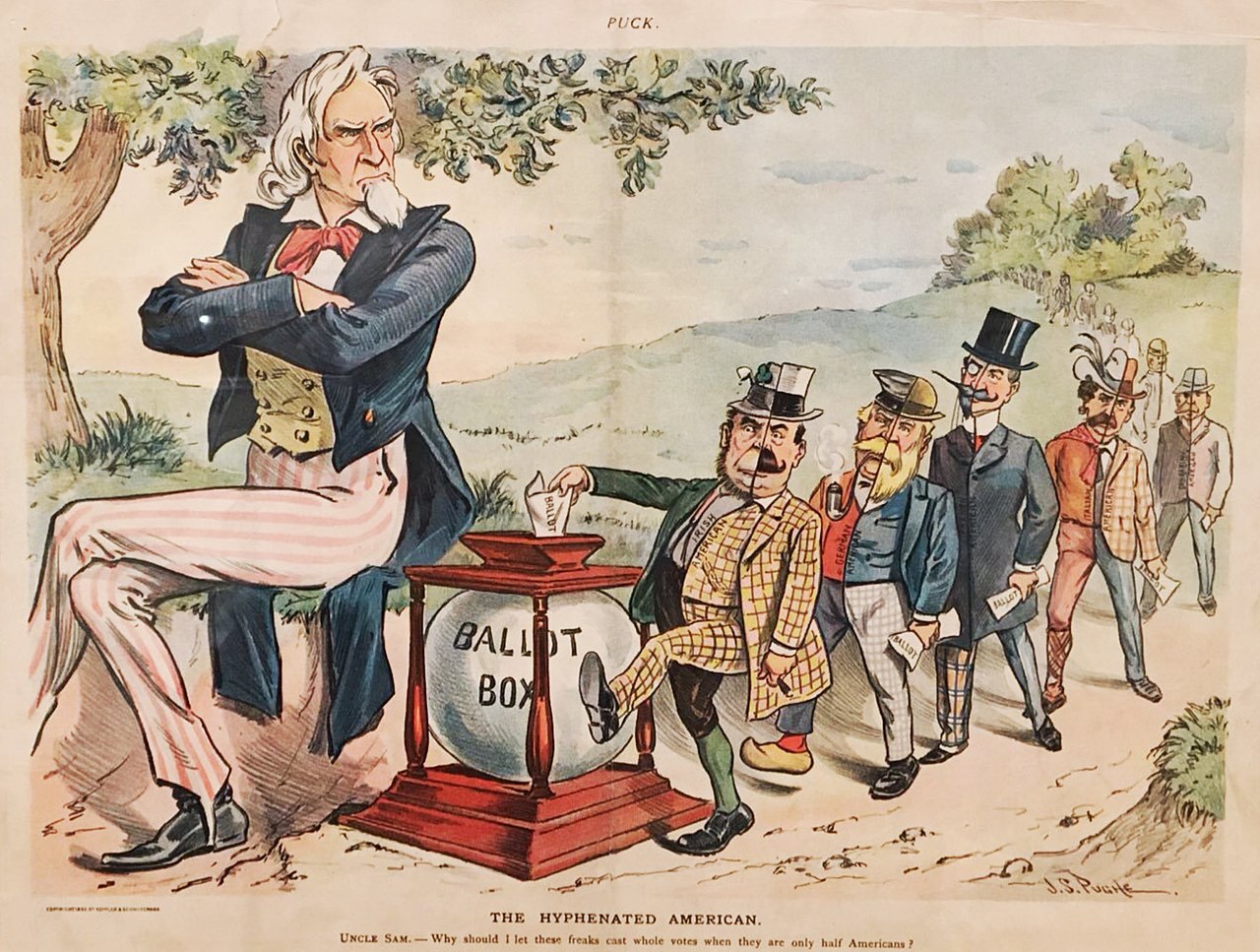

Cartoon from Puck, August 9, 1899 by J. S. Pughe. Angry Uncle Sam sees hyphenated voters and demands, “Why should I let these freaks cast whole ballots when they are only half Americans?”

Shenanigans

The novel explores the ethnic composition of Packingtown’s workers. Waves of cheap foreign labour have fed an industry which, Sinclair argues, is ‘every bit as brutal and unscrupulous as the old-time slave-drivers(p.117).’ Based on this account, it would be hard to disagree.

First came the Germans, and afterwards the Irish, who Sinclair generally casts as profiteers and political fixers. After that came Bohemians, followed by Poles, then Lithuanians, who were then giving way to Slovaks.

Having ascended a grease-laden pole, many of the Irish in the novel seem determined to keep others from scaling the heights. Sinclair’s is perhaps demonstrating that success in Packingtown depends on a willingness to embrace corruption and exploitation; at the behest of the Beef Trust itself, ‘a gigantic combination of capital, which had crushed all opposition, and overthrown the laws of the land(p.346).’

Some are damaged souls, however, such as Tommy Finnegan, ‘a little Irishman with big staring eyes and a wild aspect’, who expounds on ‘The method of operation of the higher intelligence’. Finnegan informs Jurgis that ‘shperrits … may be operatin’ upon ye(p.97-98)’

Far more sinister is the ruler of the district, Mike Scully who, ‘held and important party office in the state, and bossed even the mayor of the city, it was said; it was his boast that he carried the stockyards in his pocket.’ As a result, ‘He was an enormously rich man(p.101)’.

Eventually we learn:

It was Scully who was to blame for the unpaved street in which Jurgis’s child had been drowned; it was Scully who had put into office the magistrate who had first sent Jurgis to jail; it was Scully who was principal stockholder in the company which had sold him his ramshackle tenement, and then robbed him of it(p.287).

Yet when we do finally encounter Scully he is ‘a little dried up Irishman, whose hands shook’; who is ‘but a tool and puppet of the packers(p.288).

Jurgis’s beloved Ona is also raped and beaten by Connor ‘a big, red-faced Irishman, coarse featured, and smelling of liquor(p.167).’ In revenge, Jurgis violently assaults him, landing him a spell behind bars.

This brings him before another Irish-American, ‘the notorious Justice Callahan’:

“Pat” Callahan – “Growler” Pat, as he had been known before he ascended to the bench – had begun life as a butcher-boy and a bruiser of local reputation; he had gone into politics almost as soon as he had learned to talk, and he held two offices at once before he was enough to vote.

Unfortunately for Jurgis, Callahan had developed a ‘strong conservatism’ and ‘contempt for foreigners(p.173).’

Yet another Irishman called “Buck” Halloran, ‘was a political worker and on the inside of things(p.281)’. He employs Jurgis to enlist fictional voters for forthcoming elections in a sham democracy.

At last, we meet one Irishman, working in an enterprise owned and managed by a socialist who pays a decent wage and sets reasonable hours. He explains to Jurgis ‘the geography of America, and its history, its constitution and its laws; also he gave him an idea of the business system of the country.’ Sinclair seems to be showing that in circumstances where labour is not alienated, even an Irishman is capable of decency and culture.

How were immigrants persuaded to work in such appalling conditions? Sinclair tells us that ‘old man Durham’ (the proprietor of the Beef Trust):

was responsible for these immigrations; he had sown that would fix the people of Packingtown so that they would never again call a strike on him and so he had sent his agents into every city and village in Europe to spread the tale of the chances of of work and high wages at the stockyards(p.72).

The grotesque lie places naïve workers such as Jurgis at the mercy of a system that degrades its victims by degrees. Sadly, it was not just adults who are engaged. Thus, even the young children in Jurgis’s family group are obliged to work – and die – joining the million and three-quarter of children who were at the time similarly compelled.

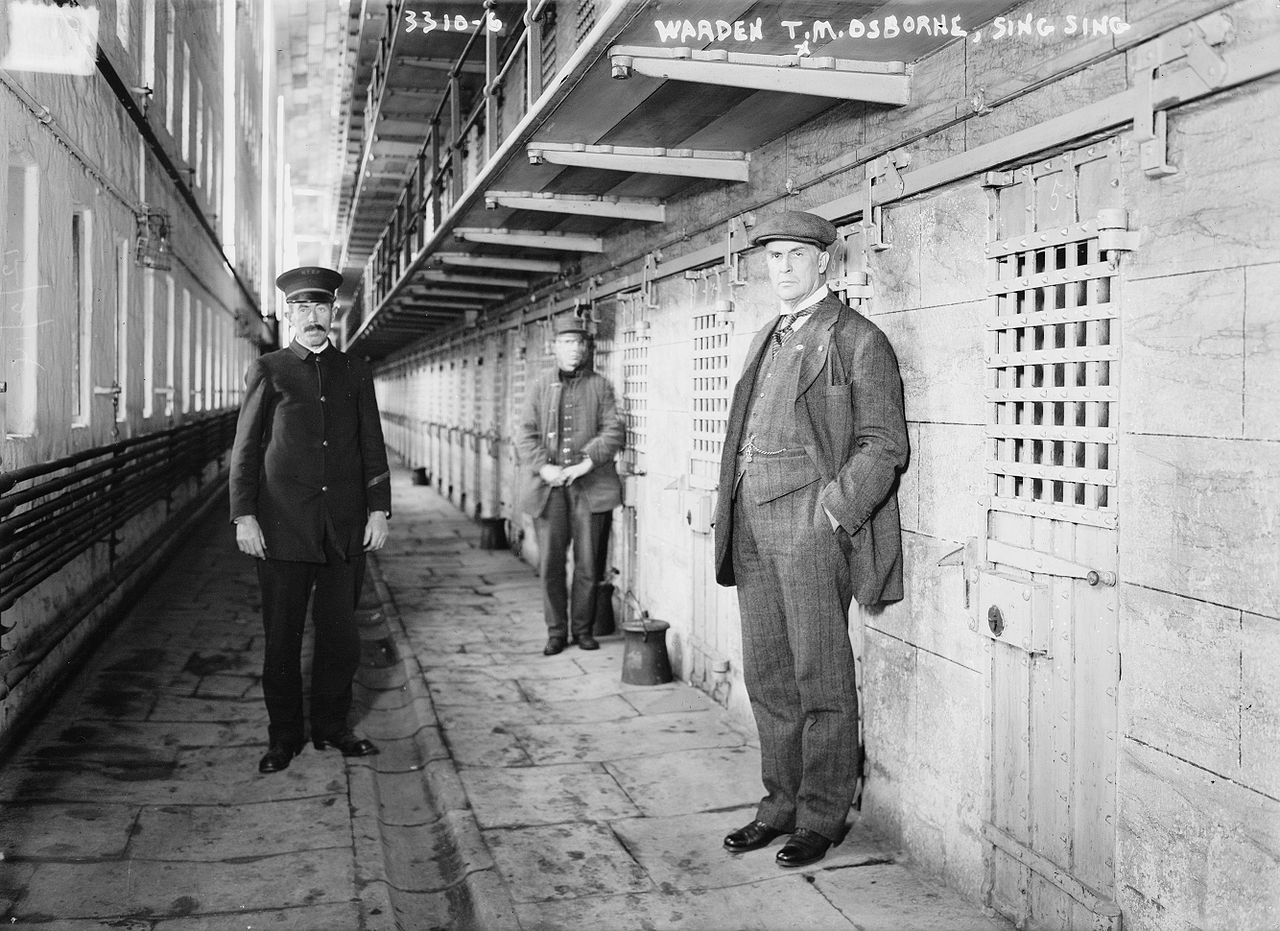

Sing Sing prison (New York). Date unknown.

Off the Rails

While incarcerated Jurgis encounters men for whom, ‘love was a beastliness, joy was a snare, and God was an imprecation.’ He shares a cell, and befriends Jack Duane, a likeable, though ultimately callous, rogue, who reveals the possibilities of a life in crime. Jurgis avoids this temptation for he still has a wife and child to keep him on the straight and narrow.

After being released from his first stretch, Jurgis is black-listed and thus unable to work. He then loses his beloved Ona to childbirth. From that point on – like so many others of his class – he numbs his pain with alcohol. He remains with the extended family group, nonetheless, on account of his baby son Ananas. But the tragedy is complete when the infant dies too – drowning in a puddle in an unpaved street.

At that point, Jurgis is a lost soul, with his dreams of a new life in shreds: ‘So he went on, tearing up all the flowers from the garden of his soul, and setting his heel upon them(p.235).’

He leaves Chicago in the spring as a hobo, working for farmers and foraging wild berries along the trail, which restores his health, but he cannot escape reminders of the old life:

Ah, what agony was that, what despair, when the tomb of memory was rent open and the ghosts of his old life came forth to scourge him!(p.244)

Thus, he returns to Chicago in the fall – like a moth to flame – where further obstacles and humiliations await. There he reconnects with Jack Duane, who introduces him to a life of crime. On their first outing they mug a man who, they learn afterwards, has suffered a concussion on the brain. This troubles the conscientious Jurgis, ‘but the other laughed cooly – it was the way of the game, and there was no helping it.’

Duane assures Jurgis, “He was doing it to somebody as bad as he could, you can be sure of that(p.279).” Duane seems to assume that ‘behind every great fortune lies a great crime.’

Jurgis’s moral descent is complete when he takes on a job as a foreman and then a scab worker during a general strike.

Brothel “The Paris”, 2101 Armor Street, Chicago.

The Only Way to Get Ahead

Jurgis’s career as a thief and strike-breaker brings a measure of financial success, implying the only way to get ahead in Chicago is to debase oneself. By then, however, having lost all family connection – and lacking a belief system – he cannot develop a stable existence. Instead, he frequents the saloons and sprawling flesh pots.

Earlier we learn of Chicago: ‘there was no place in it where a prostitute could not get along better than a decent girl(p.116)’:

Thousands of them came to Chicago answering advertisements for “servants” and “factory hands,” and found themselves trapped by fake employment agencies, and locked up in a bawdy-house(p.282).

One of the saddest episodes, among many, is Jurgis’s reconnection with Marija Berczynskas, Ona’s stepsister. At the beginning of the novel, like Jurgis, Marija displays all the characteristics of a model worker, but by the end she has been forced into prostitution in order to feed the family, and is addicted to morphine.

Prior to this Marija conducted a touching love affair with the fiddler Tomaszios, who previously spell bound the wedding party with his music. But Packingtown is no place for an artist – or romance. Marija tells Jurgis that Tomaszios has left her, having ‘got blood-poisoning and lost one finger(p.320)’ in a work place accident, meaning he cannot play the violin any longer.

Marija has interesting insights into her fellow prostitutes:

Most of the women here are pretty decent – you’d be surprised. I used to think they did it because they liked to; but fancy a woman selling herself to every kind of man that comes … and doing it because she likes it(p.327).

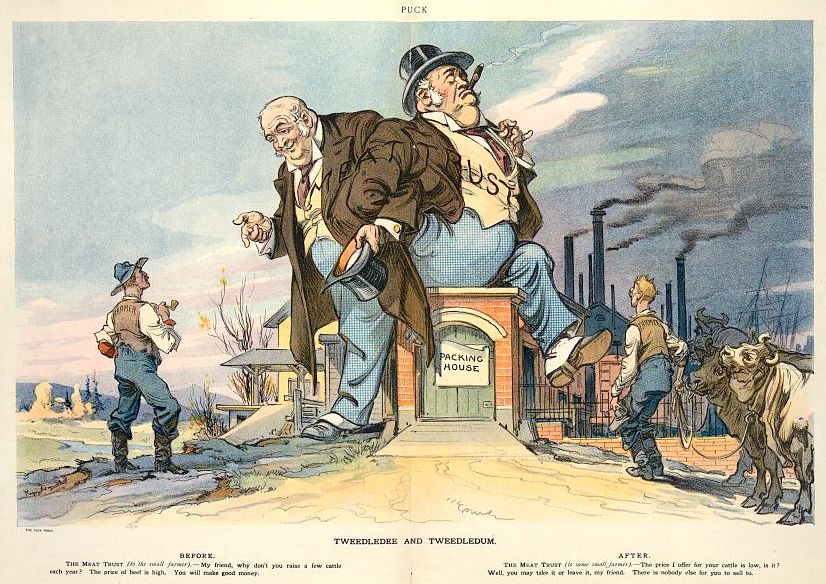

Cartoon by Udo Keppler, first punlished in New York by ‘Puck’, 15 October 1913.

Commercial Competition

Towards the end of the novel, after a quasi-religious conversion to socialism, and securing a steady job with a socialist proprietor, Jurgis meets a number of talking head intellectuals in a kind of underworld sequence.

Here he learns that the Beef Trust are just one part of the capitalist system:

There are other trusts in the country just as illegal and extortionate as the Beef Trust: there is the Coal Trust, that freezes the poor in winter – there is the Steel Trust, that doubles the price of every nail in your shoes – there is the Oil Trust, that keep you from reading at night.

This character asks rhetorically, ‘why do you suppose it is that the all the fury of the press and the government is directed against the Beef Trust?’

He informs Jurgis: ‘the papers clamor for action, and the government goes on the war path’, then ‘poor common people watch and applaud the job’, but this is ‘really the grand climax of the century-long battle of commercial competition.(p.355)’

The hysterical reaction of so many in the media to Elon Musk’s purchase of Twitter suggests that this age-old “battle of commercial competition” continues – as the billionaire class squabble over the spoils.

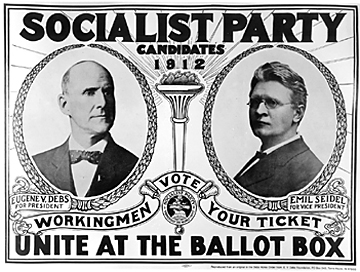

Campaign poster from his 1912 presidential campaign featuring Eugene Debs.

Much Abides

The Socialist Party of American became a powerful political force around the turn of the last century – at least until it was beaten into submission. But already by mid-century, in response to the excesses of the Soviet Union, the socialist ideal had become to many in the English-speaking world ‘The God that Failed’. A hybrid social-market ‘New Deal’ emerged under FDR in the 1930s, but neoliberalism has reigned ascendent since at least the Reagan Presidency. In today’s muddled era of identity politics, activists often lack commitment to countering the structures that produce an ever-widening gap between rich and poor.

Today, US workers are afforded far greater protection compared to Sinclair’s day, and child labour has largely been eliminated. However, in ‘the most health-obsessed society, all is not well.’[ii] Sixty percent of adults suffer from a chronic condition, and over forty per cent have two or more of such conditions.[iii]

Most Americans still live on the edge of financial ruin. A recent poll found 63% are living from paycheck to paycheck — including, remarkably, nearly half of six-figure earners, as the cost of living continues to rise.

The stress caused by this precarious existence seems to lie behind ongoing substance abuse, including an Opioid Crisis that has killed hundreds of thousands, while enriching Big Pharma that preys on the country’s pathologies. Other self-destructive behaviours – such as over-eating – are normalised in a rigid two-party political system that leaves little room for dissent.

Alarmingly, there is little sign of political change in the US, while many other countries appear to be embracing neoliberal norms. Since the 1970s inequality has spiralled, and most political radicalism seems more inclined towards self-reliance than cooperation, but as Gabor Maté points out, in what could be a commentary on The Jungle:

If I see the world as a hostile place where only winners thrive, I may well become aggressive, selfish and grandiose to survive in such a milieu … beliefs are not only self-fulfilling; they are world-building[iv].

The Jungle characterises US society as being one where willingness to participate in a “gigantic lie” underpins success. This deceit goes on, as people continue to be persuaded to buy things they don’t need, while a successful boss still extracts as much as possible from workers. It means that even some of the best, like Jurgis Rudkus and Marija Berczynskas, are still being ground down – unless they too are prepared to display the required “aggressive, selfish and grandiose” qualities that success depends on.

[i] Hugh J. Dawson, “Winston Churchill and Upton Sinclair: An Early Review of The Jungle,” ALR, 1991.

[ii] Gabor Maté with Daniel Maté, the Myth of Normal: Trauma Illness & Healing in a Toxic Culture, Random House, London, 2022, p.1.

[iii] Christine Buttorff et al, Multiple Chronic Conditions in the United States, Santa Monica, CA RAND Corporation, 2017.

[iv] Gabor Maté with Daniel Maté, 2022, p.31.