Unaware of the roaring cataract ahead, a small boy splashes in the dark river named Dodder, cheap buoyancy aids on his arms, flailing them in the manner called the dog’s paddle, eyes and mouth squeezed shut, neck stretched to keep his head above the surface. I shout a warning, which he must hear because he squints one eye open, manages an uncertain glance at me before he drops in slow motion towards the froth and blackness below, not screaming. An unseen piano makes clichéd sounds in the background and this musack is the main element that irritates me awake. I already know that all the children are safe in their beds, and this can only be a cheap movie scenario in which I am the small boy.

Even my nightmares are cinematic clichés, retribution for spending most of my life trying to avoid them. It’s a bit late for me to invent a new scenario in which life itself might be a dream, the music not potently cheap, the mise-en-scène not too close to the bone; too late to wake up and start all over again. Best to count my blessings and face the end of my ninth decade with equanimity.

Not much older than me, my island home has survived the past hundred, vaguely independent years before falling over the economic cliff. Despite having lived the greater part of my life in a contented region called Conamara in the waste of Ireland, it is impossible to avoid the suspicion that my personal and cultural identity are also falling to bits.

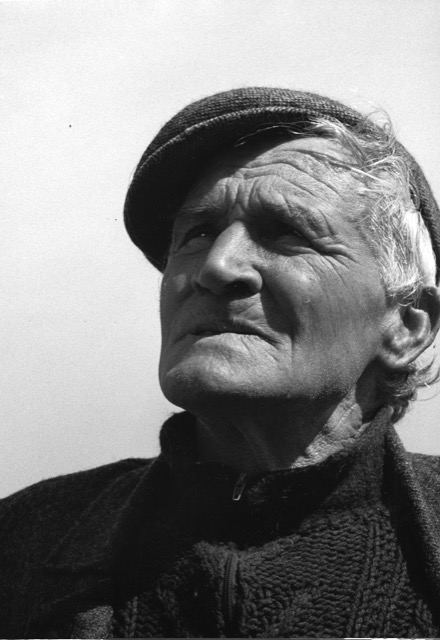

Dara Beag O Fatharta from ‘Culchies – An Excerpt from ‘A Monk Manqué’

My fellow-citizens and I have shape-shifted from being the credulous members of an imperial Roman Church, then being shanghaied as reluctant subjects of the British Empire, finally citizens of an embryonic European Empire, which looks like ending up as the Fourth Reich. But unconsciously we are, and have been for many years, carriers of the most recent imperial virus, this time North American. Now, as Hubert Butler predicted many years ago, ‘…there is nothing but Anglo-American culture to unite us.’

In this chameleon state we exist, of course, less in the literal sense than imaginatively which, in the Irish psyche, certainly in mine, tends to be more real. Our new masters’ films – pardon me, movies – and TV shows have filled our waking hours and daydreams.

Not many years ago I counted ninety cinema screens in Dublin in which not a single Irish film was to be seen. The bulk were American. Although I now require subtitles for the more recent manifestations of their staccato, one-phrase dialogue I have not quite mastered the Tarantino fashion of peppering my scripts with four letter expletives. Must try harder.

The empire’s audio-visual avalanche has forged mine, my childrens’ and my grandchildrens’ dialects and tastes. We of an older generation cannot be excused; Jack Nicholson was for long my ideal actor and Humphrey Bogart taught me to smoke fifty years ago.

The Truth of the Three Williams

It should not upset me that my grandchildren prefer Rap to O’Riada. The truths of the three Williams – Faulkner, Saroyan and Goulding – were once gospel to me. American playwrights Arthur Miller and Edward Albee were in my mind long before Brian Friel became my favourite.

We are now fortunate to speak the American dialect of English because we need go no more with our bundles on our shoulders to Philadelphia in the morning. Philadelphia has come to us in the form of Google, Facebook, Pfizer, Hewlett-Packard and the rest of the multinationals, which are now the core of our island’s economic wellbeing as well as a reminder of our anxious dependency.

The fact that up to seventy five percent of the resident I.T. multinational employees are non-Irish, while four hundred thousand of our youngest and brightest have in the last five years slipped quietly away only confuses the matter, but must not be brooded over. At least the multinational surveillance company (SGS) from which I must beg renewal of my driving license is harmlessly Swiss.

Apart from the last exception, our cultural credentials are impeccable. If forty million United Statesians are deluded enough to call themselves Irish we must be entitled to return the compliment and claim documentation as Yankee Doodle Dandies. Unfortunately the US immigration authorities now screen us potential emigrants at source, literally on our native soil in Shannon airport. As Peter Fallon urged – and I know very well I am retooling his context – in a recent poem:

Say never again to The Wild Irish Rover,

No more to The Minstrel Boy.

Give us back our sons and daughters,

Say that Ireland is over.

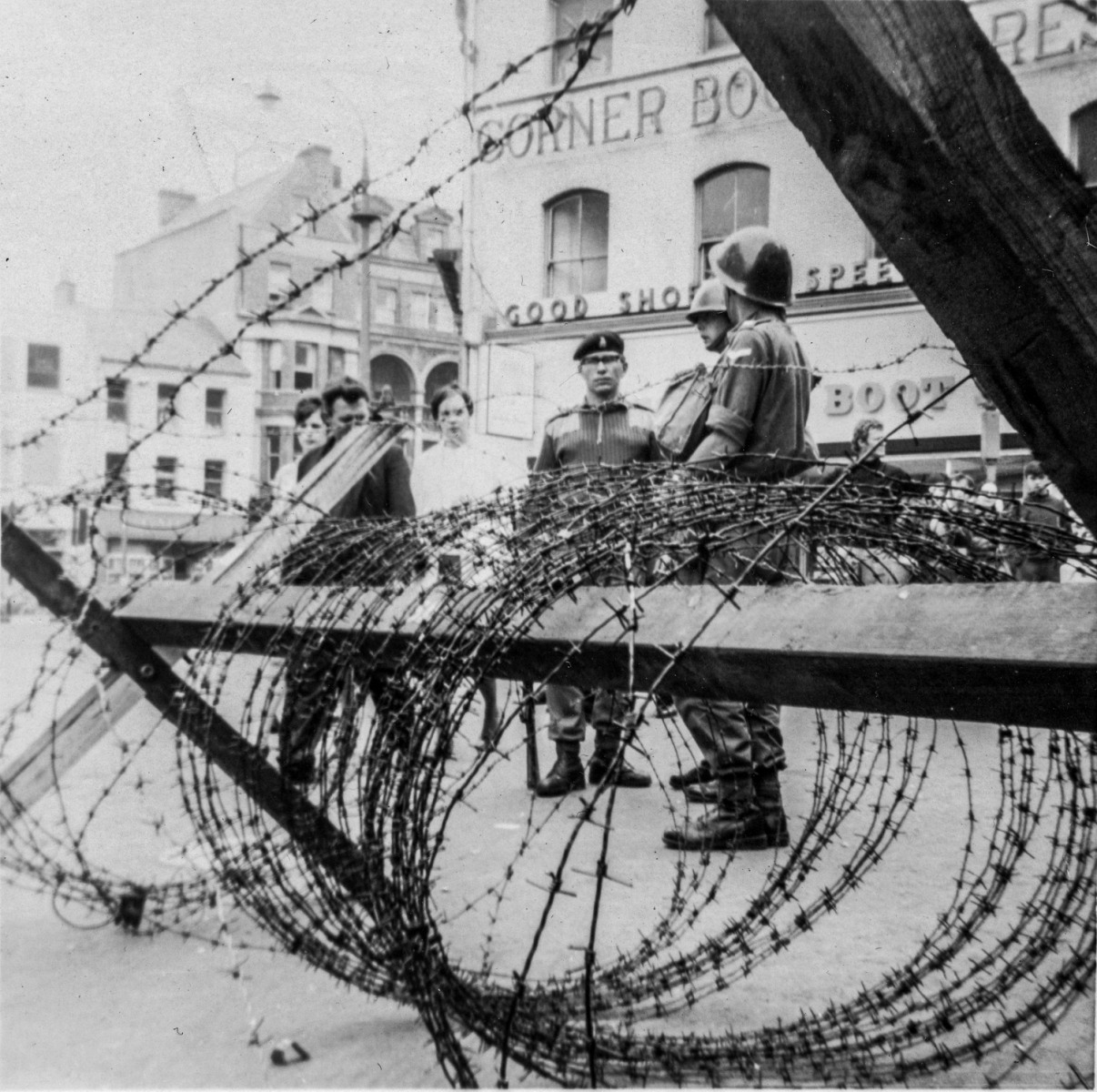

Great War

How fragile our illusions of sovereignity have been, how transformed has been this trading post in the last century, since a teenager named James Toner – along with 200,000 other Irishmen who needed a job – ran away from his home in Dublin to join the British Army. As a private in the Royal Army Medical Corps young James’ task was to collect the body parts of his fellow youths killed among the bloomin’ roses in Picardy. He survived the horror and grew up to be my uncle Jim.

I just looked him up in the British Military Archives.

Conferment of the D.C.M. gallantry award was announced in the London Gazette (1920) and accompanied by a citation:

Award Details: 61586 Pte. J. Toner. During the period 17th September to 11th November, 1918, while acting as a bearer, particularly at the capture of Bohain. There being a congestion of wounded, he repeatedly led forward squads of bearers over very difficult country during the night and greatly assisted in the evacuation of them.

This means that Jim did something foolhardy, at least under cover of night, in the midst of a carnage that was never revealed to us, his nieces and nephews.

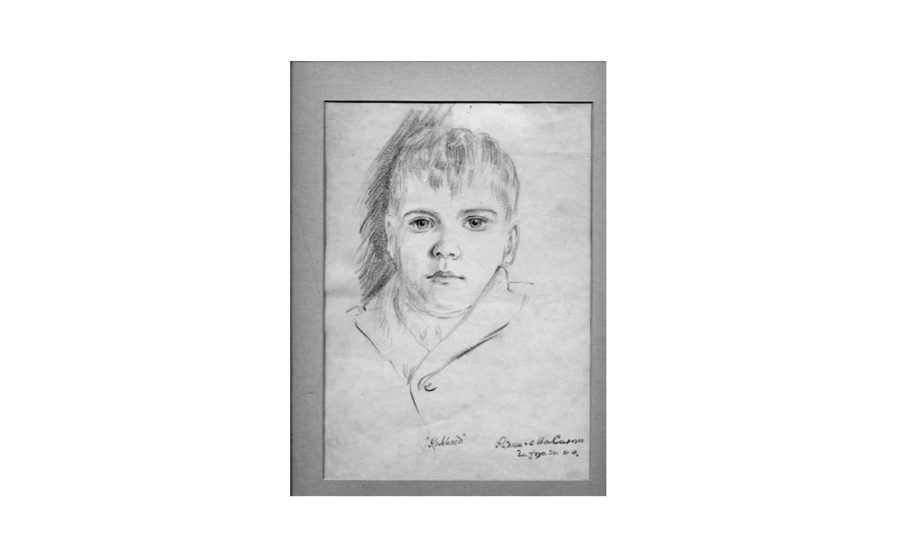

Back in Dublin with a small war pension, Jim married, begat no children and endured Irish patriotic resentment at his fighting for the Old Enemy. Even his brother-in law disapproved of him. When my father made the drawing of four-year-old me, Jim was not impressed. He acidly pronounced: “The boy may be alright, but he has the head of a bloody rogue.”

I overheard that remark and worried about it. Surely he was joking? Or was he envious because he had no children himself? I now surmise that it was general bitterness because nobody, especially not my father, wanted to hear about the horrors Jim had witnessed in France. He had been informally decreed an Irish traitor in the British army.

Sometime in the 1950s he decided to abandon his golf, at which he was local champion, and his buoyancy aid, whiskey, and put an end to the pain that was identified too late. It is now called post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and is applied to the euphemism ‘veteran’. Uncle Jim put an end to his pain with the aid of a gas oven.

There are other associations. When the British army abandoned our sacred soil in 1922, Uncle Jim’s sister Kathleen ran away with her boyfriend, a Tommy named George Thomas.

A possible fatal attraction was the fact that both of their fathers kept pigs; science now says that personal odour is a most powerful sexual signal. I met the ageing lovers in their home at Abingdon, Berkshire in 1964 when Uncle George unexpectedly said to me: “I glory in you, Bob.”

I think he meant that I appeared not to have inherited my father’s prejudices against the English. He was wrong; our parents’ prejudices are lodged in our DNA but, as a form of energy, can happily be redirected at more fitting targets, such as the English Public School system and all their imitators closer to home. Oh, the bitther word!

When World War II (like War Number 1, a civil war between blood brothers, the Germans and the English) came along, one of Uncle George’s sons, Sidney, enlisted as a teenage frogman and acted, at nineteen, as one of those cockleshell heroes who attached limpet mines to enemy ships. He became a hero of mine and survived to produce a pretty daughter named Cathy whom I subsequently persuaded to elope with me briefly to Ireland where we had midnight swims at Killiney beach and were referred to as kissing cousins. Cathy later married a Red Devil, one of those RAF people who put on daring aerial displays.

Born in the Pale

These connections make me wonder if I am not still a bloody rogue and worse, a fellow-traveller of that suspect class, a West Brit rather than a putative citizen of America.

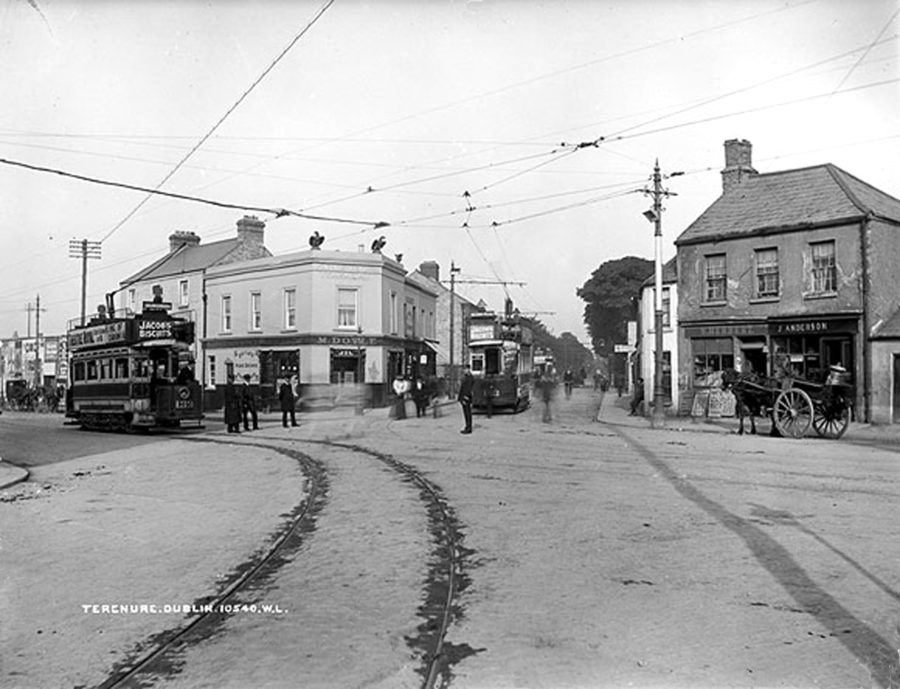

For a start, I was born in the Pale: Dublin and its environs. My first language was English, albeit in a dialect light years away from the BBC accent, whose Home Service provided most of my childhood listening pleasure; Radio Éireann broadcast only a few hours per day.

My early reading was what we called the comicuts, The Rover, The Hotspur, The Eagle, all published in England. My favourite authors were Robert Louis Stevenson, Arthur Conan Doyle, G.A. Henty, Agatha Christie, P.G. Wodehouse, John Wyndham, Leslie Charteris and so forth. Even the Irish language detective story writer Reics Carlo, who was obligatory reading in school, turned out to be English.

But as I grew up I betrayed them all for the likes of Irwin Shaw, Kurt Vonnegut, Norman Mailer and Hemingway, and now I know I’m a virtual Yank. I assure you that this is less a form of ingratiation with the American Chamber of Commerce than one of realisation and resignation. No problemo.

There are more ingredients in this cultural Irish stew.

Among our official heroes, Pádraic Pearse’s father was from Birmingham; James Connolly came from Edinburgh and James Larkin was a Liverpudlian. No wonder I am ambivalent about nationalism, Irish, English and American and still cling to that long-lost cause: socialism.

The last night of the Proms in the Albert Hall disturbs me, with its sea of Union Jacks and Hooray Henrys rendering Land of Hope and Glory – because I am moved by Elgar’s music (although he did not write the lyrics, which are as Kiplingesque and vainglorious as Deutschland Ueber Alles).

When filming American schoolchildren with their hands on heart, reciting the daily oath of allegiance to their flag, I am also uneasy. Indoctrination of the unruly young starts early on that continent but, by contrast, nationalism has in recent years become a vulgar word in Ireland.

How do the British and the Yanks get away with their jingoism? And where, apart from everywhere and nowhere, do we Irish really fit in? To those who, like myself, find all of this disconcerting I say, cop on, get a life, get the message, get over it, get with it, and other such novel and useful imperial edicts. No worries.

Staying for a moment with the phenomenon of British and American nationalism, I wonder if the answer may not be that they were both empires whereas Ireland’s only imperial conquest was spiritual – mainly among the black babies of Africa – and that appears to have been erased by our national amnesia. As very soon must happen to me as, dragging my feet like a reluctant schoolboy, I approach four score and ten, intending that looming watershed to be more an act of defiance than any petty celebration.

‘Yourelookingreathaventchangedabit’

On my ninetieth birthday I shall beware of those who say: “You’re looking great, haven’t changed a bit.”

My exact contemporary, the late Ben Barenholtz, a survivor of Naziism and a New Yorker, who produced Coen brothers’ films and gave me a present of a book of all of Cole Porter’s lyrics, told me that he has an ex-friend, a liar who has said exactly the same thing to him every year for the past twenty years.

The astonishing thing about this compliment is that we ancients believe it. We skip and dance down the road until we are forced to pause, whereupon we resemble the silent nun in Elizabeth Jenning’s poem who was breathless with adoration. We oldies, by contrast, have merely run out of breath, full stop, or period, as I should really learn to say.

The truth of the above platitude, ‘yourelookingreathaventchangedabit’ is simply this: we are decommissioned. Joseph MacAnthony has described our aged generation as tourists in the departure lounge. We exist, persist, only in our anecdotage.

Who would have thought that little Riobárd, the boy in the drawing, would survive so long? Certainly not himself, whose life expectancy as a film and TV maker was long ago estimated by an insurance Actuary to be no more than forty five years.

What matter that this little Jackeen has spent more than half his life in the least colonised part of Ireland – the Gaeltacht of Conamara which, paradoxically, he has long known to be spiritually and economically closer to Boston than to Dublin.

Who gives a tinker’s curse that the Jackeen in question, having read so many comments, references, articles, essays, even PhD theses about his minor oeuvres, now dares to give his version of the story? But age confers a protective veneer of immunity, anonymity, even a kind of invisibility on the elderly so one is free to say what one likes.

As Kurt Vonnegut – who in one of his modest communications to me referred to himself as an old fart who smokes Pall Mall – put it: “Old men are obscene and accurate.” We can experience a kind of lightheaded bliss when we notice our fuel gauge moving towards empty and we can offload petty concerns.

The present words are thus an act of memory, which is equally an act of imagination and may be approached academically as sub-Proustian because although my life sentence has been long these sentences are, with a few exceptions, not.

I also possess unlimited memorabilia – photos, letters, diaries, the usual bric-a-brac of a life – which may save me from downright lying. Besides, there are those modest films which constitute aides-memoire and, not least, may be treated as having been personal buoyancy aids, otherwise described as vain aspirations.

I occasionally wonder, as I float towards the brink of the cataract, if I do not exist in some other, gentler person’s nightmare?

Enjoy further episodes from Bob Quinn’s A Monk Manqué on Cassandra Voices