In August of 1969 I was driving across Ireland with the late Bearnard Ó Riain, the older brother of a good friend of mine, the late Dinno Ryan. Most of my old friends are now ‘late’.

We were going to join others in a mountain-walking weekend. Bearnard had participated in the nineteen-fifties IRA campaign in the North of Ireland, was captured and interned in the Curragh. He could not stand being locked up and he signed a statement renouncing his involvement in the IRA and undertaking to leave Ireland. He had gone to Africa, married an English girl named Carol, had two children and spent the next ten years there. The marriage had broken up and he was now back in Ireland to gather his resources.

I switched on the car radio to get the news and we heard that the North had exploded again, that Orangemen were burning Nationalists out of their homes in Belfast.

[ngg src=”galleries” ids=”3″ display=”basic_slideshow”]He turned to me with a look that said: ‘I have to go up there’. I knew that he needed some distraction from his domestic circumstance. I also suspected he needed to exorcise his old guilt at signing himself out of the IRA and I turned the car northwards.We arrived in Derry as the Rossville flats siege was ending. On the roof of the flats we met Bernadette Devlin. Bearnard asked her if we could help in any way. ‘You could help to clear up this mess,’ she said and we started clearing away the broken bottles and stones, remnants of Molotov cocktails.

We found a bed for the night on the floor of RTE reporter Seán Duignan’s City Hotel bedroom. Word came that there had also been serious trouble in Dungiven. Seán was excited, predicting a civil war.

Belfast

The following morning we drove to Dungiven, which was now peaceful, recovering from a night of violence. It was all very anti-climactical. I later wrote an article which the Evening Press published with the title: ‘Trouble will always be where I am not.’

The same applied to Belfast. The only sign that there had been trouble on Bombay Street was a lone figure whose bald head I recognised from newspaper photos as belonging to Joe Cahill. He was keeping guard with some kind of rifle.

Bearnard and I acted like tourists and strolled up the ravaged street. Encountering some suspicious young men of whose allegiance we could not be sure we prudently claimed to be Canadian journalists. Our years of travelling had smoothed the rough edges of our Dublin accents so that we could pass ourselves off as harmless.

The following morning we investigated a burnt out factory on, I think, the Falls Road. Someone shouted ‘sniper’ and everybody dived for cover. I could not take it seriously and simply lined myself up behind a lamppost. If there actually was a sniper in the factory building, I reasoned, he would need to be a very good shot and at worst I could only be winged.

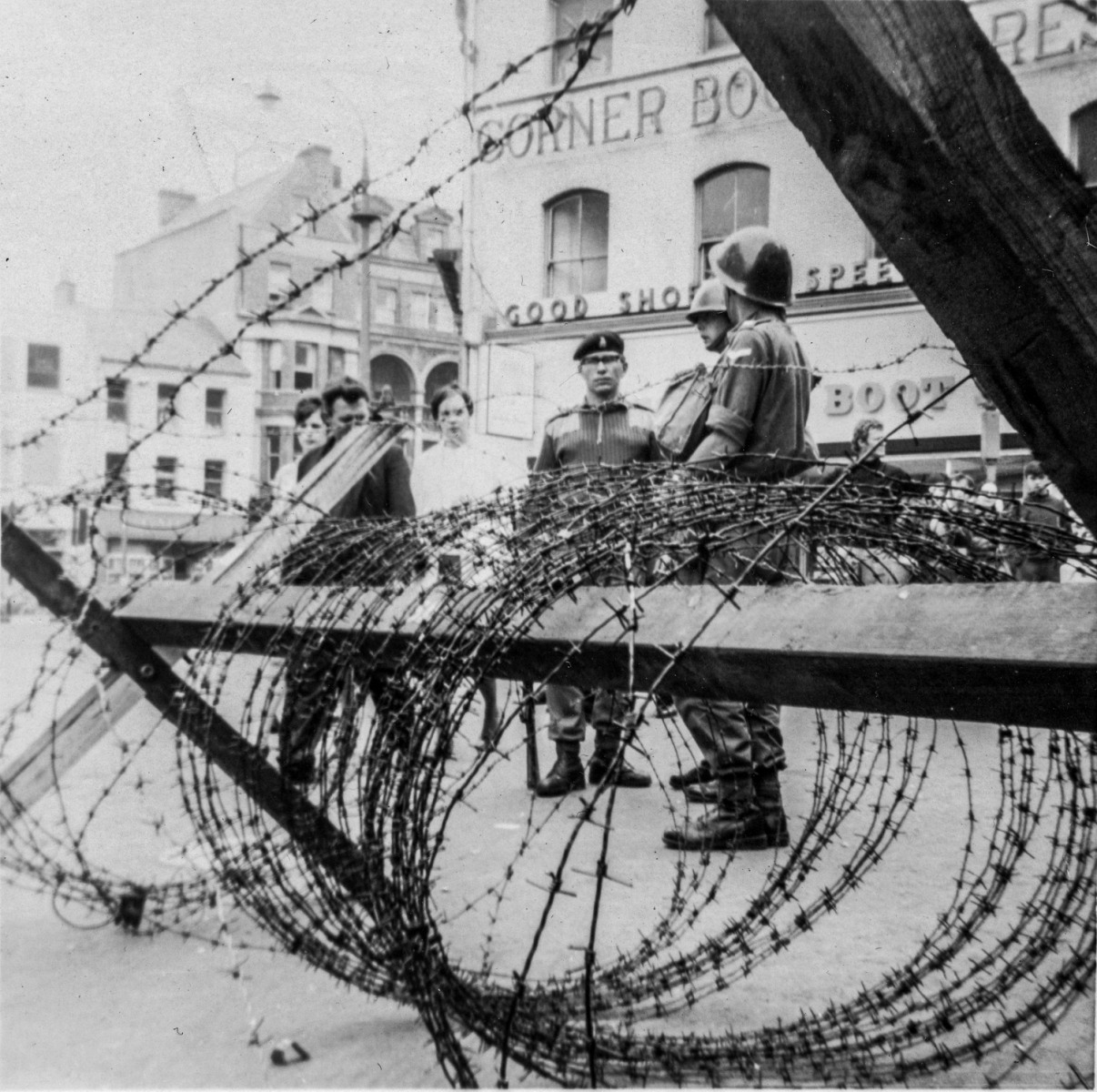

But there were no shots. I was beginning to think the whole situation was quite exaggerated by journalists. Later that day we witnessed the first contingent of British soldiers taking up positions on the Falls Road and being applauded by the grateful citizens. What struck me was the nervousness of the lieutenant in charge and the gaucheness, the mystified expressions of the soldiers under his command.

How were they – or we – to know that we were witnessing the beginnings of a Nationalist revolt and an occupation and vicious war that would dominate our island for the next thirty years?

The above mentioned Bearnard O Riain lived in Johannesburg. He had written a most interesting memoir of his dramatic life. It opens with the scene of a drunken man kicking a woman lying in the gutter. To his horror, the writer realises that the woman is his wife and he himself is the violent drunk. Bearnard’s book is quite unlike my fanciful reminiscences. It is that unique object: a well-written, honest memoir. No publisher in Ireland was interested in publishing it.

It would be five years before I again braved the North of Ireland, next time as the guest of ‘Official’ Sinn Féin.

Conamara

By 1974 I was entrenched in a cottage in Baile na h-Abhann, Conamara where TG4 would be built over a score years later.

A softly spoken man named Eamon Smullen called one day. He had the idea of making a film on the subject of the epic poem, Caoineadh Áirt Uí Laoire. It had been a favourite of mine in school. He could even offer some money to make it.

I jumped at the chance. It took me six months to research, write and direct the film with an amateur cast entirely from the area. It took a few more months to edit and finish it. Essentially it was a tragic love story.

The (true) context was a hopeless one-man protest against the Penal Laws imposed by the English in the 18th century. Joe Comerford and myself were the only crew with film experience, Joe on camera, myself on sound. My then wife Helen was the indispensable production support.

When the film was finished, my neighbours – including the cast of the film – were a little bewildered by my quite unconscious use of Brechtian alienation techniques. This was a pragmatic solution to the problem of using an all-amateur cast. I needed to creep up on and defuse, audience prejudices against both amateurs and the Irish language.

I did this by using authentic native speakers rather than urban Gaeilgeoirí and scripted it accordingly as an amateur rehearsal with roughly dramatic re-enactments. It worked very well because it offended the proper targets. When it was shown at the Savoy cinema in the Cork Film Festival, actors Niall Tóibín and Donal McCann happened to be seated behind me. At the end Niall tapped me on the shoulder and whispered: ‘Quinn, yer a clever hoor.’

That was as fine a compliment as I could get and certainly took the sting out of the Irish Times’s Fergus Lenihan describing the film as ‘formless as the Connemara rocks.’

Dermot Breen, Director of the Festival, was delighted to be offered the film – the only other Irish entry besides my friend Louis Marcus’s fine Waterford Glass job.

Naturally I thought my baby was a work celebrating the genius of Conamara but, considering the pleasant expectations of film audiences, Louis’s beautiful cinematography won.

Later, Dermot Breen who was double-jobbing as Irish Film Censor, demanded cuts to certain mild profanities in my English subtitles – e.g. ‘shit’ and ‘Jesus’. I refused and he confined the film to viewers over sixteen years. The Dublin premiere was launched by Síobhán McKenna in the Drumcondra Grand cinema in 1975 while I was having a quiet little breakdown.

Dance Hall charge

It also seemed a good idea to show it at the first night of our little ‘cinema’ in Carraroe in the same year. Although I was entirely to blame for the film the titles included a credit for the ‘Education Department of Sinn Féin’ of which Eamon Smullen was director and who had provided the £6000 towards its making.

The war in the North was in full swing; Sinn Féin was split into Provos’ and ‘Stickies’. I had no interest in either group, nor in the subtleties of North/South politics. All I saw was an opportunity to make a film about my favourite poem in Irish, which is still a landmark in Irish literary history.

Oblivious to the political implications I went ahead with the job. But politicians have longer memories than their constituents. I had previously, on our closed-circuit video, made fun of the Minister for the Gaeltacht’s poor command of the language of the Gaeltacht. There were two political black marks against me.

Thus on the night of the Carraroe showing of the film the local Garda arrived at the door asking to see my licence to show films. No such licence existed. The only legislation the State had ever bothered to enact concerning film was the Dance Hall Act of 1935. Nobody could dance in our cinema because the seats were bolted to the floor.

The Garda, a decent man named Rice, mentioned the suspicion that I was raising funds for the IRA! I was summonsed to appear in court on the Dance Hall charge. It was a petty case of political harassment and the Garda was the messenger: don’t mess with the Minister, the message said.

The Case for the Defence

George Morrison of Mise Éire fame brought a sample of old flammable nitrate film as an exhibit in my defence. This was the dangerous stuff for which the British had legislated in 1904 and which had long fallen into disuse.

George intended to ignite an inch of it and detonate it in court as a smoke bomb – a game we had played as children. The demonstration would show the difference between it and the modern safety film which I handled.

Perhaps fortunately, George did not get the chance as the case was summarily dismissed with no blot on my escutcheon. Nevertheless some of the mud stuck and forever afterwards I was considered locally to be somehow not politically kosher.

Officially, I was bordering on the subversive. When some maverick IRA man named ‘Mad Dog’ McGlinchy was being sought high and low throughout Ireland there were only three houses searched in Conamara. One of them was mine. The Special Branch found and formally confiscated a child’s popgun which did not work.

Belfast drinking club

President Cearrbhaill O Dálaigh had a private peek at the film in the Project Theatre in Dublin and wrote a complimentary note to me. Film critic Ciaran Carty had kindly described it as ‘the Irish film I for one have been waiting for.’

But the film was not really respectable until the Northern war was over. It has never been shown on RTE but TG4 is more daring and have shown it twice. When Channel Four showed it they cut out the credits for Sinn Féin. Meantime Eamon Smullen wanted to show the film in a Republican drinking club in Belfast and brought Joe Comerford, cameraman, and myself up there.

The film also seemed to confuse that audience. A lady turned to us and asked: ‘What are yiz? Some kinda antellectuals?’ While we were there the club was raided by the British Army who moved silently and grimly through the crowd.

I found it strange that there was no heckling, not a voice raised in protest and deduced that, yes, there is something frightful happening in this part of Ireland.

We were accommodated that night in the house of a man named Billy MacMillan whom I gathered had been shot by the rival Provisional IRA. In Ireland the first thing on the agenda is the split.

I noticed a man in the tiny back yard of the house carrying a revolver, presumably to protect us. It felt as if we were in a film. We were escorted to the eight-o’clock train the next morning by Eamon Smullen, the gentle man who had asked me to make the film.

At no stage did I feel in danger. I think I must sleepwalk through life, incapable of taking anything seriously, not even the darkness. All is at arm’s length. It still surprises me that

Caoineadh Áirt Uí Laoire has become a kind of icon in the lexicon of Irish film making. In recent years it was exhibited for a month in Trinity’s Douglas Hyde Gallery. It was also featured in the Irish Museum of Modern Art as an example of the work of modern Irish artists.

A couple of years ago it was restored and Joe Comerford and I showed it in Derrynane, the Kerry home of Daniel O’Connell’s family which features in the film. In the introduction I mentioned the film’s small budget.

Poet Theo Dorgan was present and later in the pub said to me: ‘I know where that £6000 came from. I think I even know the post office from which it was stolen.’ I still hope he was joking.

SUPPORT Cassandra Voices with a Patreon Donation CLlCK HERE

Bob Quinn directed Poitín, the first feature film entirely in the Irish language, while his documentary works include the four-part Atlantean series tracing the origins of the Irish people. His recent memoir A Monk Manqué is being serialized in Cassandra Voices.