Such sad news. Another member of the Irish Women’s Liberation Movement is gone. Not just any member, but Dr. Moira Woods, one of the three founders.

She was something else. By the time us younger ones were venting our rage outside Dáil Éireann in blue jeans and curly hair, thinking we were the bee’s knees, Moira had already shaved her head in support of victims of tarring and feathering in the North, conducted a mock trial of Richard Nixon on the back of a lorry during his visit here, carried an effigy of him on a coffin to the American Embassy, and burnt it. Another day she suggested setting her coat alight in Church in protest against the latest Catholic Church outrage.

Talk about fearless.

She was also very clever and enjoyed film star looks. As Marie McMahon put it, ‘besides being by far the most beautiful person in the (IWLM) group to look at, which is an awful sexist thing to say but it’s true! she also had a brilliant sense of humour. And was extremely politically courageous’.

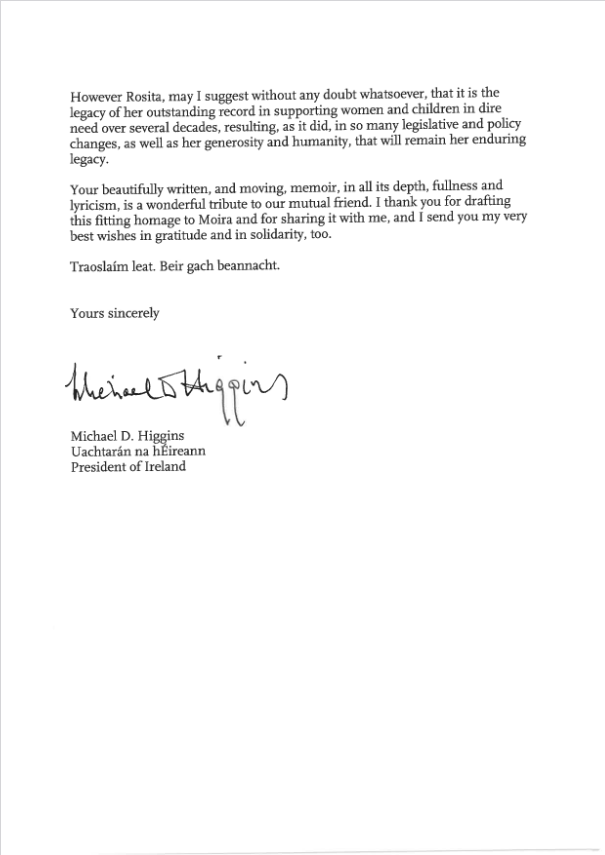

1950s Ireland. Image: Richard Tilbrook (wikicommons)

Early Years

Born in 1934 – a child of the Raj – to an English father and an Irish mother, her family were stationed in Burma before being evacuated to Australia after the Japanese invasion. She was then sent ‘home’ to be educated by nuns, where according to Susan McKay she ‘received thrashings and expulsions’.

She was, nonetheless, a brilliant student, ready to matriculate for Oxford aged just fifteen, but switched at the last minute to study in Trinity to allow her begin her medicine degree at sixteen.

‘In her final year’ writes Susan McKay, she won ‘a medal for psychiatry, a gold medal for surgery and the hospital prize for medicine.’

Her first marriage was to a fellow student, Roger Hackett. They had two children.

She later re-married, a surgeon Bobby Woods, who was aged sixty-two, while she was thirty-one. Mary Maher, Woman’s editor of the Irish Times and fellow member of the IWLM said she had ‘never seen a happier marriage’. They went on to have four children.

While raising her family, running the big house on Ailesbury Road – Deirdre McQuillan remembers her ‘at the stove cooking something wonderful while children and people milled about’ – she became intensely committed to political justice – protesting against the war in Vietnam, the Dublin Housing Acton Committee, and the Northern Troubles.

Snooty neighbours were not always impressed. The Woods were accused of being ‘communists’, of harbouring Viet Cong. Neighbouring children were forbidden from playing there.

I don’t think it took a feather out of her. She had bigger fish to fry.

A mural outside the Bernard Shaw Pub in Portobello, Dublin depicting Savita Halappanavar and calling for a Yes vote in Ireland’s referendum on repealing the Eighth Amendment.

Justice for Women

More and more, she joined the fight for justice for women, so that one day she and Margaret Gaj, owner of Gaj’s on Baggot Street, and heroic fellow fighter for justice Máirín de Burca – fresh out of jail for pelting eggs at Richard Nixon’s car the same day Moira was conducting her mock trial – got together in Bewley’s on Grafton Street and decided – HURRAY! – to found the Irish Women’s Liberation Movement.

Pretty much every gain made in rights for women in Ireland can be traced back to that modest get together of these three women.

This was an Ireland where women were discriminated against from the day we were born. As we detailed in our pamphlet, ‘Chains or Change’, in every aspect of their lives women were hobbled.

This began with an education system which funneled us into our designated roles as wives, mothers and caregivers. After primary school we were obviously too thick to do higher level mathematics, thereby excluding us from most properly paid careers, from medicine to airline pilots to bank manager. If a few ladies managed to jump through the various hoops, the infamous Marriage Bar lay in store.

Once married you were out on your ear, and it wasn’t just for civil service jobs, but also banks, accountancy firms, respectability itself demanded you go home and become, literally, a ‘chattel’ inside your marriage, where you enjoyed few civil rights. Legally you barely existed.

Your husband could flip over to the UK, divorce you, get full custody of your children and sell the family home from under your feet – all above board!

Having made sure marriage was the only ‘career path’ open to women the powers that be – the celibate elite of the Catholic Church and the politicians who kowtowed to them – aimed to turn us into little more than domestic servants and baby-making machines.

There was no sex education, no contraception, and absolutely no termination of pregnancy available. Talk about going to war blindfolded, with your hands tied behind your back!

@RositaSweetman provides new testimonies from survivors of Mother and Baby Homes, and calls for a criminal prosecution of the Catholic Church and full redress.https://t.co/Tas0iA0BPV#MotherAndBabyHomes #motherandbabyhomesreport @broadsheet_ie @amandaknox @AliceHarrisonBL

— CassandraVoices (@VoicesCassandra) January 22, 2021

Mother and Baby Homes

Life was less dire for middle class, urban women, but the damnation of a Mother and Baby Home awaited most working class and rural girls unfortunate enough to become pregnant outside of wedlock.

For many unfortunate middle class women locked into marriages – ‘drowning in babies’ in Nuala Fennell’s immortal phrase – Valium taken by the bucket load was the only source of comfort.

And women were still ‘churched’ after giving birth, that is brought in and ‘cleansed’, as if birth itself, so ferociously trumpeted by the good fathers, was filthy.

As Nell McCafferty famously found out, you couldn’t even get a television on the never-never without a male signature. Even if that male was unemployed and pulled in off the street and you’d just been hired by the Irish Times.

Naturally Moira became the go to person within the IWLM for all matters medical, and psychological. June Levine remembered warmly comforting words from Moira when accessing a nasty memory during a consciousness raising session in Gaj’s, revisiting a man thrusting his penis between the bars of her cot.

As Moira increased her involvement in women’s rights the damage wrought on our society by crazy levels of inequality, and repression became clearer to her.

It helped that she had been brought up outside of Ireland. She remained a Catholic, but totally rejected ‘Rome’s’ assumption that it could regulate women’s reproductive lives down to the minutest detail.

Her presence as an educated and privileged woman carried weight. On a practical level, as one of the few women in the IWLM with ‘means’ she was, as Máirín de Burca says, ‘always there to bail us out of the Bridewell after we’d been arrested. She was incredibly generous. I once landed a homeless family on her and she just took them in.’

By the late 1970s, Moira was helping set up the first Well Woman Centres, the country’s first menopause clinic, and had begun seeing patients referred to her by the Rape Crisis Centre.

Image (c) Daniele Idini.

The Eighth Amendment

1983 was the year when the backlash against the liberalisation of life in Ireland began in earnest, Moira was at the forefront of the campaign against the insertion of the Eighth Amendment to the Irish Constitution..

Right-wing Catholicism, representing the most repressive aspects of the religious Patriarchy, had marshaled its forces. Recalling the names of the various organisations sends a shiver down my spine: PLAC, SPUC, the Congress of Catholic Secondary School Parents’ Associations, the Irish Catholic Doctors’ Guild, the Guild of Catholic Nurses, the Guild of Catholic Pharmacists, the Catholic Young Men’s Society, the St. Thomas More Society, the National Association of the Ovulation Method, the Council of Social Concern, the Irish Responsible Society, the St Joseph’s Young Priests Society, and the Christian Brothers Schools Parents’ Federation.

Passing the infamous Eighth Amendment, giving a foetus equal rights to life to that of the mother, inserted into the Constitution was their sole aim. Shamefully, three separate governments allowed themselves to be terrified into submission and the Eighth was ‘in’.

It was a bruising battle, and Moira was at the centre of it.

Within a year of ‘winning’, the disastrous consequences for young women became apparent. Thus, schoolgirl Ann Lovett was found bleeding to death in a grotto in Longford – her little baby lying dead beside her.

Six months later Joanne Hayes was to be crucified on Ireland’s terrifying patriarchal altar, having been wrongly accused of the death of a baby found on a strand eighty kilometres away.

An indication of just how desperate things were for young women comes from a remark made by the undertaker who buried the little one found on the strand. He lived beside a quarry, and said it was not unusual to find babies bodies thrown there by desperate mothers.

How could a society descend to that level of brutality?

Cassandra imploring Athena for revenge against Ajax, by Jerome-Martin Langlois, 1810-1838.

Sexual Assault Unit

Moira’s next move was to head up a Sexual Assault Unit in the Rotunda. As Emily O’Reilly wrote in a piece for the Sunday Business Post in 2002, Ireland’s first SAU ‘sprang indirectly from the 1983 anti-amendment campaign’ after discussions between Anne O’Donnell, Moira and Dr George Henry, then Master of the Rotunda.

Dr. Henry had seen SAU’s in Australia, setting one up in an Ireland reeling from sexual violence and guilt, seemed obvious and Moira was the obvious person to put in charge.

She set about doing things with her usual vigour, but was soon stunned at the tsunami of cases coming her way involving abuse, incest and rape. The outer limits of sexual violence.

It was a rape case that once again pushed her centre stage. The so-called ‘X’ case.

A suicidal fourteen-year-old girl, pregnant as a result of rape, was taken to London by her parents to see if they could extract DNA from the foetus for a court case against the perpetrator and were told that would involve a high risk of miscarriage.

When her parents asked the Gardaí if DNA from the foetus could be used in evidence the Gardaí immediately informed the Attorney General, who sought an injunction, granted by the High Court, compelling the girl and her parents to remain in Ireland.

In the High Court Declan Costello ruled that despite the rape, the age of the victim, and her being suicidal, she had good loving parents and so the pregnancy must go ahead.

Five days later an appeal was lodged in the Supreme Court, which decided that termination, in England, could go ahead.

The child miscarried two days later in a London hospital. Moira was the doctor in charge. The misery wrought on those parents, and that raped, suicidal fourteen-year-old being put through by the system, left her shaking with fury.

Tragically for her it put her in the cross hairs of the latest iteration of misogynistic religiosity.

Working alone, with absolutely minimal resources, Moira had seen over 1,000 children in the Rotunda. Incest, barely mentioned at the time, was one of the biggest problems presenting.

Moira’s methods of work were unheard of at the time in Ireland. She actually spoke to the children, and used ‘anatomically correct dolls’ to help them demonstrate what had occurred.

She also named fathers she deemed guilty of abuse, which was also unheard of. As Deirdre McQuillan says the practice had been to keep fathers in the family no matter what.

The ‘no matter what’ was of course crucial. As Sebastian Barry has been so eloquently shouting out in publicising his new novel, God’s Old Time, abusing a child or a young person is akin to murdering them. Protecting the breadwinner – no matter what – could, and often did, mean abandoning the child.

As one lawyer who saw the subsequent crucifixion of Dr. Moira Woods unfolding put it, ‘part of the problem was she was way ahead of her time. In those days there was no culture of reporting abuse. People wouldn’t believe you, they didn’t want to believe you, that a father had sexually abused his daughter.’

‘If it happened now there would be much deeper investigation, and she wouldn’t be in any trouble at all’.

Sadly it was then, and not now. And the bad people won.

The example of Matt Talbot's piety was used by the Irish Catholic Church in inculcate subservience as the downtrodden were told to await their reward in heaven.https://t.co/8uOS8DgHKe@broadsheet_ie @vincentbrowne @fotoole @connolly16frank @gemmadunleavy1 @AlanGilsenan1

— CassandraVoices (@VoicesCassandra) January 20, 2021

War of Attrition

Moira’s stellar career in unflagging support for Irish women and children was mired in vileness, heaped on her by those desperate not to be named.

Just as happened with Dr. Noel Browne over the Mother and Child Scheme in 1951, the medical profession stood idly by as one of their finest was thrown to the wolves.

It was a five year, savage war of attrition, with the Medical Council producing a redacted report (as is standard Irish practice), which, wrote Emily O’Reilly, concluded ‘while Woods was found not to have observed proper protocols, it makes no claims about the validity of the accusations.’

‘Proper protocols’ were demanded while working alone, and completely under-resourced, in a bat-shit, sexually dysfunctional country.

Moira didn’t appeal.

My lawyer friend said, ‘she’d had enough’. She had just separated from her partner of twenty years, and father of her two youngest children, Cathal Goulding, and decided to leave town to live in Italy.

Deirdre McQuillan says it makes her happy to think she found a new, good life there. Met with an Italian man, Guido, ran a big house, and kept in touch with home via the steady stream of visitors from Ireland, her eight wonderful children and grandchildren – Penny, Denis, Christopher, Catherine, Timothy, Benjamin, Aodgán and Banbán with grandchildren Ben, Erin, Jack, Rowan, Katharine, Oisín, Clíodhna, Darragh, Sophie, Emily, Sophie and Cathal.

I’m torn between rage and sorrow thinking about her. Her valour. Her beauty. Her passionate advocacy for Irish women, that ‘the issues on which she campaigned throughout the 1970s and 1980s resulted in twenty changes of legislation involving women,’ (according to Stephen Dodds in the Irish Independent in 2002), and the shameful way she was treated by an embedded, religiously inspired, misogyny.

It is terrifying how blackening people’s reputation works; how repressing the truth works, including taking injunctions out against biographical works. Indeed, Google searches for one of Ireland’s greatest advocates for women, show up pitifully little information.

Here’s hoping she’s up there with the Great Spirit in the Sky fashioning flaming swords and thunderbolts to hurl down on her torturers – they know who they are. You! And You! And You!

Rest in Power beautiful Sister.

Rosita Sweetman received this message from Moira’s old friend President Michael D. Higgins in advance of the publication of this appreciation.